We meet by Green Park at noon, just round the corner from Richard Nagy’s new gallery on Old Bond Street, and a pretty little restaurant that looks good for lunch. Over gnocchi and a little wine, Lewis tells me about how he was first drawn into the world of Egon Schiele, the subject of the upcoming exhibition, and his entrancing debut novel.

"I was living in Prague, when I began to see all these drawings, mostly erotic pictures, strewn around the city. For weeks, I kept seeing them around, wondering what was going on, before finally realizing they were advertising an exhibition. By this point I was rather taken in by these pictures, so I went along, and happened to read – next to one of the paintings – an 800-word biography of Schiele… It only took my reading about 200 words before I was hooked."

He stopped writing stories about "guys in North London breaking up with their girlfriends" and began what was to become The Pornographer of Vienna – a lively, compelling account of Schiele’s short life, tainted by a "syphilitic father, that questionable relationship with his sister… the hypocritical marriage, and their tragic death two days before war ended."

Indeed, Schiele is at times a difficult character to like, a challenge that Crofts admits was sometimes tough: "A friend of mine read the book, and afterwards told me, "You know, I actually ended up not like Schiele very much". And I said, "I agree!" But one of the key things about doing biographical works is that these great men are often very flawed, and as a writer you have to be sympathetic anyway. I mean take Walk The Line, or Ray – both of these men had huge drug problems, loads of affairs – they beat their wives – they were often awful people. But they also wrote great music, and their lives were great stories, and people want to know about them."

And Schiele’s life – as re-imagined by Crofts – is a brilliant story. The Pornographer Of Vienna charts the student rebellions, dangerous liaisons and dramatic relationships of Schiele as a young man in the debauched and fascinating Vienna at the turn of the twentieth century – "pregnant with squalor behind its Imperial veil." With compassion and a careful interest in the "little character traits of a great artist", he gives a very special insight into the complicated man behind those transfixing paintings. He gives a new sort of intimacy to portraits renowned for that closeness:

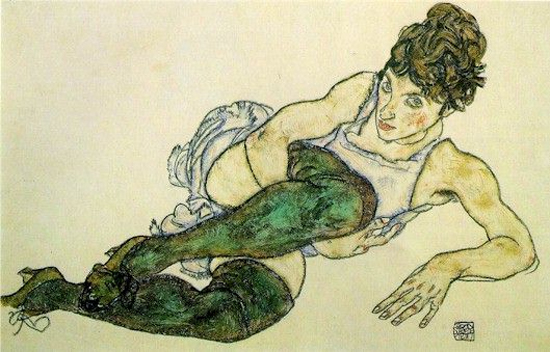

"I think there’s a quality of frankness in Schiele’s work that you don’t find elsewhere. Most depictions of intimacy have something secretive, clandestine, limited, about them… Schiele’s are very frank, while steering clear of being blatant or unforgiving. I’m still not sure how he pulls it off."

Is it appropriate, then, that Crofts gives Schiele a similar treatment in his own portrait of the artist. Croft’s writing is straightforward and clear, and close; he brings us right up to the infamous, difficult Egon, he shows us his flaws and his insecurities and his narcissism – never putting him on a pedestal and indulging in idol-worship or bravado – but also avoiding judgment or distraction. He captures Schiele’s gaze – that dark, playful, curious gaze – that steady focus. Looking at the portraits of Schiele next to the book, it is clear that Crofts has achieved a good likeness.

And as for the women in the novel, in Schiele’s life – and in Schiele’s art, as the upcoming exhibition will focus on – Crofts treats them, too, with grace and compassion. He introduces Wally, Schiele’s lover and muse, whose auburn hair and sad blue eyes light up several portraits – as well as his seductive, petulant sister, and melodramatic mother. He shows us the models, the girlfriends, the used and the loved – the subjects of the Mayfair exhibition this year. And where we are used to wondering about the women behind the erotica and the infamy, the presumptions and scandal, Crofts uncovers some substance, some stories – some sadness, too.

But I will not ruin enjoyment of the book by going into any more detail – I will not tell of the broken hearts, torn canvases and smashed glasses behind those sublime portraits. I will simply recommend that before stepping into the gallery to see Schiele’s women, before giving in to those inviting, and yet careless gazes, you read about the background debauchery and poverty, the "stale beer stench of Vienna", the models and muses in the "groping shadows of dance-halls… the blood sea running over lace". Those reclining women, and that narcissistic man, seem even more entrancing after an acquaintance with their chaotic past.