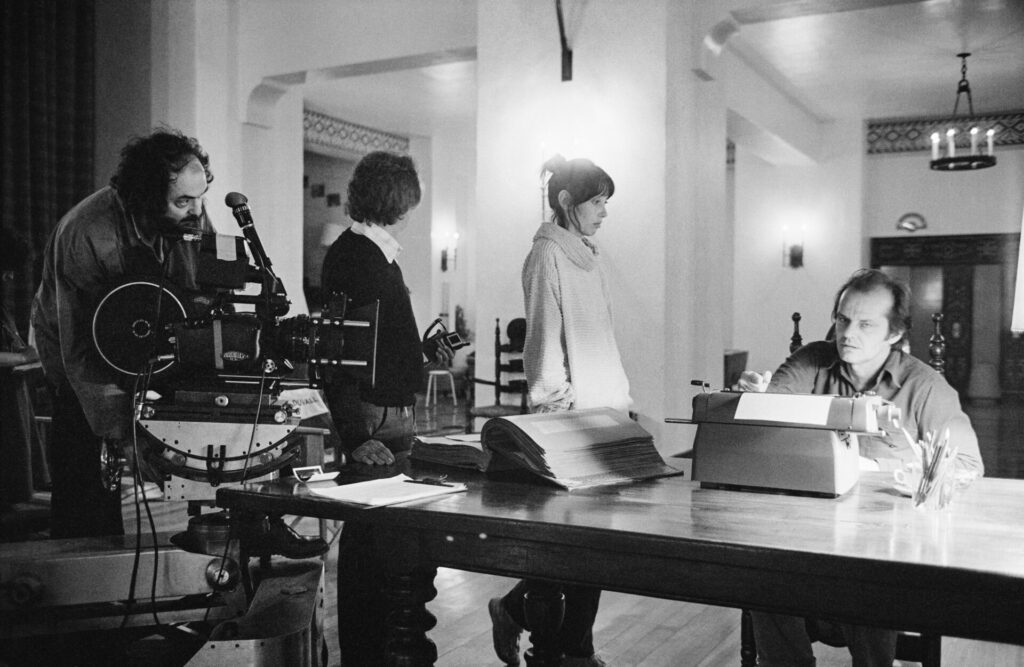

On Friday, April 11, Stainforth began cutting in music cues, though nothing had been finalised yet in terms of composers. “Stanley suddenly says one day to me, ‘I’d like you to do the music editing,’” he recalls. “He did not have the music planned at all until a very late stage, really until the film was more or less completely cut, so the music had to be done very fast. One reason he asked me was that he, physically, could not be in two places at once. While I was doing the music editing, he was going to be in the dubbing theatre the whole time, doing the premixes of the dialogue and effects. When he asked me to do the music editing, it was definitely presented as a bit of a crisis, in that we were running out of time. It was very much presented as a bit of a challenge. He said something like, ‘Will you do it? Because I’m counting on you,’ ever so slightly threatening. I said rather boldly, ‘Yes, I can do this thing!’ Because I didn’t feel daunted at all, but completely gobsmacked to be given such a fabulous job.”

“I remained involved in the editing right up until the end,” says Gill Smith, “and we continued to take it in turns to work with Stanley. At or near the end of cutting, he gave us all the 1920s, ’30s music. He was certainly listening to these and all the Ligeti and Sibelius, and the Wendy Carlos music.”

“We did an awful lot of material for The Shining,” Carlos says. “A ton of music.”

On April 19, Carlos and Elkind delivered a good deal of their music, including ‘The Rocky Mountains’ and ‘Flying over Rockies’ for the Torrance family drive. In all they sent Kubrick two albums’ worth, twenty-four tracks, such as ‘Thought Clusters’ and ‘Winter Maze’. “When The Shining track arrived,” says Stainforth, “I think six takes, direct from New York, with varying amounts of the Rachel Elkind vocal backing – it was obvious straight away that it was absolutely perfect for the opening of the film. Superb. It took Stanley all of five minutes to select the best take. He just said something like, ‘Okay, Gordon, take four’ and I dropped it in.” (This cue is called ‘Shining Title Music’ on Carlos’s later collection of music for The Shining.)

Elkind would recall that repeated exposure to the movie while composing had become “nightmarish,” particularly the aspect of an artist who can’t create, and said that they wrote about four hours of music. An April 30 note on a music chart indicates that Carlos’s reworking of Berlioz’s ‘Songe d’une Nuit de Sabbat’ (“Dream of a Witch’s Sabbath”) was delivered around that time as well. Even though Kubrick approved two of their tracks, and would use other material Carlos and Elkind had composed, he decided that he didn’t want to use their main efforts. “All Carlos’s music arrived and Stanley was very dissatisfied with it,” says Stainforth. “By then he’d made up his mind that the way to go was with Penderecki and Ligeti.”

“And so we failed in our attempt,” says Carlos. “We’d been working with the material that was in the book, and trying to make music that fit the mood of an updated Gothic horror story. And of course the stylization that came out from the filming was not present in the book. That [music] just never was going to work when the final footage was done.” According to Elkind, they heard the news only indirectly and would describe her experience on The Shining as not a very happy one.

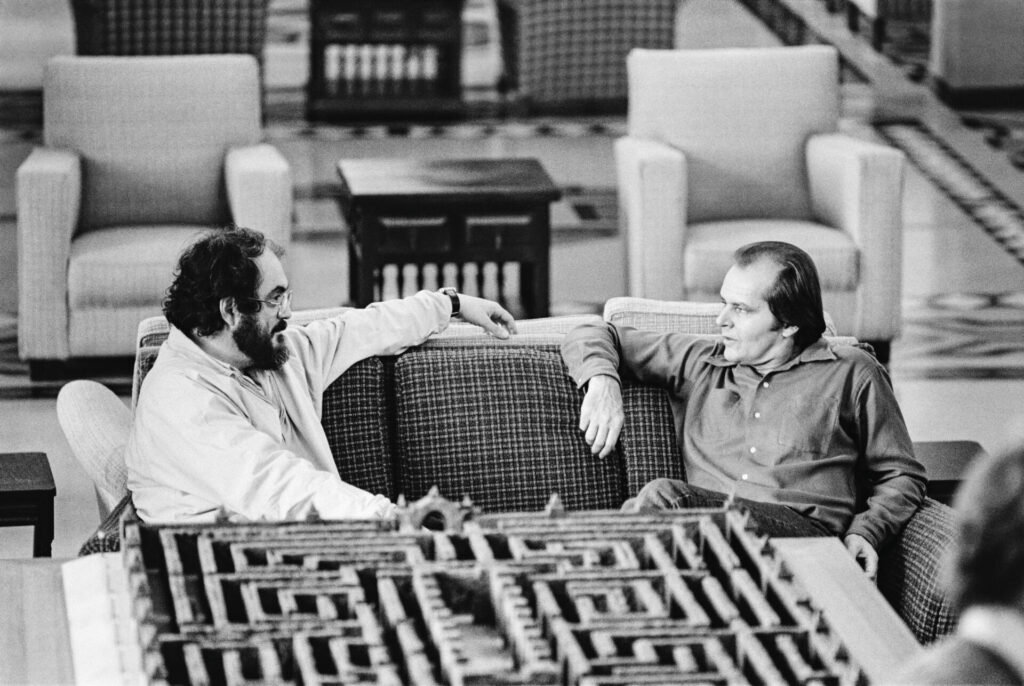

As he had for 2001 and Barry Lyndon, and to some extent on Clockwork Orange, Kubrick had decided to use music that had already been composed by masters, as recorded by the best orchestras. Vitali recalls: “Stanley said, ‘The world, Leon, is the biggest music library you’re ever going to see. So you might as well use it, if you can.’

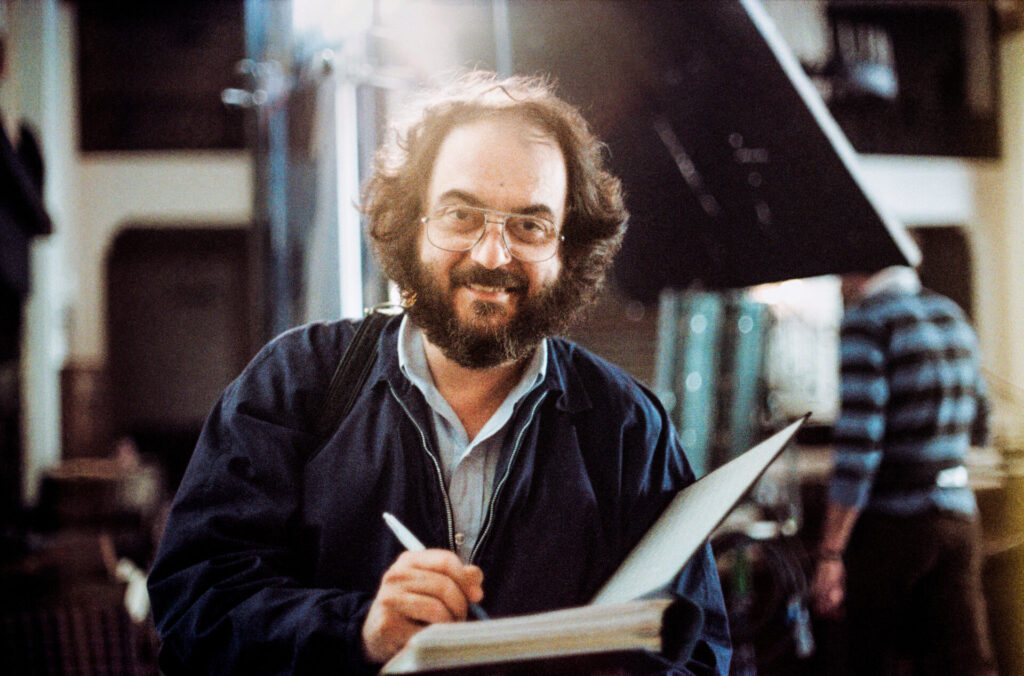

“Stanley had initially commissioned an original score,” adds Stainforth, “and although it was very fine in its own way, he felt increasingly during the postproduction that the film needed something altogether more disturbingly freakish and manic. Stanley was very keen to use Penderecki’s music and told me to get hold of everything that he’d ever recorded. It amounted to about fifty hours in total, which took me about four or five long days to listen to. Stanley told me exactly where he wanted each music cue to start and finish, and told me to lay up whatever I thought worked, giving him, if possible, a choice of about three or four different pieces of music per cue. Each evening he would listen to a bit more of what I’d laid up during the day, and then I’d work often late into the night – twice right through the night – making final changes and drawing up the final neat music charts for dubbing the next day.”

“Stanley did have a great ear for music,” says Merrin. “I’ve worked on so many movies where the film is great, and you’re waiting for the extra music that would lift the whole thing up, emotionally, and it fails miserably; it just doesn’t work. He did it the other way around, and that was good. He loved every minute, you couldn’t get him away. Once you got him in that dubbing theater, it was difficult to get rid of him. I did say to him actually, ‘You are trying to do too much. You are trying to do everybody’s job, and some people are capable of doing it better than you are.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Yeah, but I need to know about everything.’”

“I had never done any serious music editing before,” Stainforth says, “apart from some films of my own I made at film school and laying some music for some television documentaries. There was very little discussion, but Stanley was very positive and would make snap decisions in every case when I played him my choices, and then let me very much get on with it.”

“We were all working incredibly long hours,” Stainforth adds. “With some of the more complicated reels, I would send the music tracks over to the dubbing theater, so that he could have a trial run-through with Bill Rowe at lunchtime, or when they had a spare moment during the main dubbing. The incredible thing was that I was hardly in the dubbing theater for more than about one minute.”

“An enormous amount of effort went into this,” says Harlan, whose musical background made him a useful advisor to Kubrick, “in getting these rights, having a kind of spooky but good music, which Stanley liked. For example, the Bartók ‘Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta’ is a gorgeous piece, but at the same time, it has this glitter of spookiness. And he sometimes mixed it with Penderecki, quite naughty. But it works very well. And Wendy Carlos’s contribution is important, because the ‘Dies Irae’ from Berlioz, from the ‘Symphonie Fantastique,’ has been taken and electronically changed. This is originally Berlioz, and Wendy Carlos made it into this music that instantly tells you in the beginning: This is not for National Geographic.”

“When Jack is beginning to go nuts,” Vitali adds, “it’s very ceremonious, with a lot of chanting that goes on underground. It sounds like a chorus of religious devotees. You have this trilling falsetto. You have a very threatening bass line, then you have another track on top of that with strings and percussion, and another track of effects, which were used in a musical way. So the effect was an amazing build of sound running alongside the picture. There is some Béla Bartók music going on, and on top of that there is this heartbeat, all of it abstract, but full of tension and fear.”

The ‘Heartbeats and Worry’ track was something Carlos and Elkind had created, and it often became part of the soundtrack landscape. Carlos recalls: “Stanley wanted these sounds that would just sneak in and go by. He called them ‘low-flybys.’ They were sounds that would just sneak into you, subconsciously.”

Stainforth says: “Stanley and I really were on the same wavelength about using the music as a counterpoint to the action, rather than underlining the emotional content of the film in the simplest possible way. Often the really obvious pieces of music worked surprisingly badly when you tried them with a particular scene. The vast majority of Stanley’s creative decisions were made simply on the basis of whether they felt right, and only very rarely for some deeper arcane, intellectual reason. He was very much more of an intuitive artist in the way he worked than an analytical intellectual. Not only did he not like people discussing his work in an overly analytical way, I think he resisted any such tendency even in himself, as being fundamentally at odds with a true creative process.

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, by J.W. Rinzler and Lee Unkrich, is published by Taschen