For a young man growing up in the backwaters of 1980s Devon – and for many other like-minded folk currently orbiting their thirties and forties like dilapidated Russian space stations – British comic weekly, 2000AD, this year celebrating it’s 35th anniversary, was a crucial first step toward the kind of oblique, gaudy entertainment regularly featured in the Quietus (meant in the highest possible sense, of course). That technicolour spider’s web of horror movies, comics, pulp sci-fi paperbacks and lewd, singed rock & roll that constitutes a crucial part of my daily cultural intake can be traced back to those first, over-a-big-kid’s-shoulder glimpses at 2000AD’s pages. Its credit list reads like a who’s who of big name comics innovation. The likes of Grant Morrison, Simon Bisley, Brendan McCarthy and Alan Moore all had work published in 2000AD during its heyday, and some of the characters they and their colleagues created during that time have gone on to become trash-culture icons and instant point scorers in any game of Nerd Tennis.

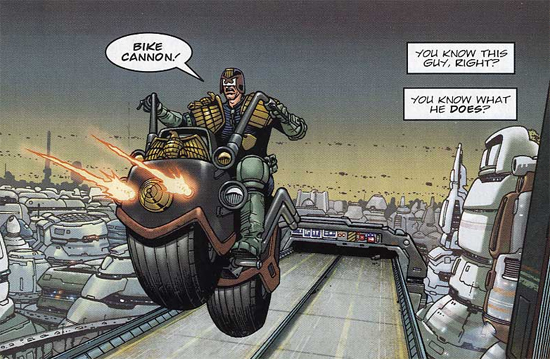

When thinking 2000AD you remember the crystalline, steampunk stylings of Nemesis The Warlock, mechanised Dirty Dozen, The ABC Warriors, the ribald adventures of shape-shifting warrior oaf, Slaine. But most of all, towering above them like a Mega City tower block, you think of Judge Dredd Chin out, gun out, helmet on, dispensing the law (justice a distant second) to any perp, creep, or crim that steps out in front of his Lawmaster motorbike. You think Batman is comics’ ultimate badass? He doesn’t even kill people! Dredd would off you for taking a leak against an Aldi! However, like a lot of total bastards, he’s rather popular. His strips have been syndicated all over the world and he’s become a four-square cultural icon, adapted for computer games, appearing on album covers and an unlucky recipient of thespian tribute from Sylvester Stallone.

A large part of Dredd’s continued popularity has to do with the rich and elaborate world he inhabits. Crafted by 35 years’ worth of name creators, Mega-City One, the futuristic megalopolis that is Dredd’s beat, is a character in itself, outclassing all other comic book cities, from Akira’s Neo-Tokyo to Batman’s Gotham, in its size and scope. Ever evolving and containing a variety of grotesques to shame a Hogarth or Grosz, The Big Meg, as it’s known to its unfortunate inhabitants, is a vast sprawl, dominating nearly all of the far future Eastern seaboard, packed with bezerk cyborg killers, anti-gravity surfing champions, robot manservants and massively obese, wheeled psychopaths amongst a writhing multitude of others.

Recently, Dredd’s adventures and the city that contains them became the inspiration for an album from soundtrack composer Ben Salisbury and Portishead’s Geoff Barrow. The two originally got together to work on the upcoming Dredd movie, but decided to continue and complete the work off their own backs. The final result, Drokk: Music Inspired By Mega-City One, is therefore an imaginary soundtrack, designed to accompany the Big-Meg daydreams of fans of the Galaxy’s Greatest Comic and to reflect Geoff and Ben’s personal interpretations of the futuristic city. It’s a low-key, unsettlingly sparse record, pulsing with night-drive atmospherics and sudden drops into oceanic whorls of time-stretched instrumentation. As a musical representation of a late night Lawmaster journey through the streets of Mega-City One it’s spot on, so I dropped Ben and Geoff a line at Geoff’s studio to find out about the album’s creation. The conversation starts with the revelation that Geoff never understood Nemesis The Warlock. Cue wounded sense of Colegate disbelief…

You never got Nemesis the Warlock?

Geoff Barrow: No, I never did. But just to set things straight, I’m the 2000AD reader and Ben isn’t.

Ben Salisbury: We’re not hiding the fact. It sort of worked to our advantage as I could look at things from a purely musical point of view. Although since finishing the record I’ve been pestering Geoff and he’s lent me loads of copies of the comics and I’ve started getting into it…

Good Man

BS: …but while we were doing the album I wanted to come at it from an outsider’s musical perspective. Geoff was the one with his head in the comic world.

Did you think that getting into the comics would be a bit of a distraction?

BS: Yeah I suppose it would’ve been.

GB: There’s a lot of information…

BS: Especially coming at it cold.

GB: Comic readers generally pride themselves on the tiny little nuances of information they can freak their mates out with.

Yeah, we do…

GB: I’m nowhere near that, so it was a bit daunting.

The biggest influence on the album sounds to be John Carpenter…

Both: Never heard of him…

It’s weird with Carpenter, isn’t it? He seems to have become one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century without really trying.

GB: He is!

BS: For mine and Geoff’s generation he seeped into our consciousness. That handful of films that have Carpenter scores that we watched growing up. That sound world has a massive element of nostalgia for both of us. And not just Carpenter but the other peripheral music around that time, the Terminator stuff and the Vangelis stuff. When Geoff came to me with this project it was memories of those scores that got me into it.

I’m presuming it was a deliberate play on your part to take a non-Hollywood route and avoid using strings?

BS: When we first started off, because of my background scoring natural history films and working with orchestras, it was always tempting. I’d say to Geoff, “It could be really dramatic here if we could just slip some strings in,” But Geoff would resist, and he was absolutely right. We had to keep it pure to the sound world we were dealing in. There’s a temptation in my day job to automatically reach for the orchestra, it’s so lush sounding. But it just gets boring because it’s a sound that people are completely and utterly used to, however big or expensive it is.

GB: You don’t actually hear it any more. Unless you’re going to write completely anti-melodic, discordant pieces, then strings are what the brain expects. It’s true of many big films. Loads of them don’t even have themes really, just massive drum hits. That music will never push you further into the feeling of the film, like the work of John Carpenter, which is incredibly sparse, or Ennio Morricone with his different themes and techniques – whistling, distorted guitars. These things are not so prominent in the popular films they’re making nowadays.

BS: It feels like me and Geoff are part of a mini-bandwagon, in that people are starting to change the way they approach film soundtracks. Directors are looking more to musicians from Geoff’s background rather than your traditional, Hans Zimmer bombast. The Trent Reznor soundtracks, the Drive stuff, they point to this growing unease that these generic film scores…

GB: Are just that.

BS: They’re very boring. You can have an orchestra of a thousand, you can have fucking cannons firing! It just doesn’t have the impact that it used to. Stripping stuff away, doing something on a kazoo and ukulele, is way more arresting than a hundred people sawing away on violins.

GB: It’s a different parameter.

There’s an enjoyable amount of dissonance on the record as well isn’t there? That’s one of the strange things about soundtracks, it seems that people are quite happy to listen to atonality in the context of a film, but if you played them dissonant music outside of a multiplex they’d be turned off by it.

BS: That’s been one of the plusses of soundtracks from the start: putting atonal music into people’s ears.

GB: That’s always what pulls me into the soundtrack world as well. Often they’re non-traditional, song based pieces. The kind of stuff that you’d only really find in experimental music such as avant-garde jazz and psychedelia. Soundtracks were, I suppose, the commercialised version of that, but often even more extreme!

BS: Your question nails a really key point in the importance of soundtracks, which is bringing atonal, experimental music to the public and having them not bat an eyelid to it, whereas in the concert hall…

GB: If they put it on a Florence and the Machine record people would shit themselves.

Literally, one hopes…

GB: Ah, Florence fans do already.

So what are your personal favourite soundtracks then?

GB: I’ll start with (John Carpenter’s) Assault On Precinct Thirteen. I can’t fault it.

BS: I’d definitely agree with that one. I hadn’t seen the film for ages and while we were working on this project Geoff was playing me the music and showing me bits from it. It’s just how unsettling the sparse electronics are. In some ways it’s really naive.

I love the Morricone stuff where he almost pushes into the realms of cheesiness…

GB: When he was working with Sergio Leone he thought it was funny. There are lots of his pieces that have actual comedy to them. The Good The Bad And The Ugly is an ultimate massive soundtrack. Incredibly well written, emotionally tense, comedic, all those things. That would have to be up there as well.

BS: It’s a different world but some of Bernard Hermann’s stuff I’ve always loved. Even the ones everybody knows, like Psycho, they’re fantastic. He knows how to ratchet everything up with an orchestra.

GB: And they’re popular because they are that good.

BS: And there are great people writing today. The Thomas Newman (American Beauty, Revolutionary Road, Revenge Of The Nerds) stuff has got over-exposed but I love what he was doing. Even the classic John Williams scores are good in their place.

GB: There’s obviously a movement towards something more interesting. There always has been through independent cinema, but it’s becoming more difficult to release films, to get them made, and even if you get them made to get them distributed.

BS: And when there’s lot of money involved and it’s got backers who aren’t prepared to take a risk it’s difficult.

I presume that the discipline of making a soundtrack piece differs to that of going into a studio and making an album?

GB: I found it easier. I think it’s different if you’re actually working on a picture. The idea of working to a timeframe and edits and emotional changes. That’s something I know nothing about and I’m really eager to learn, and that’s what Ben is obviously very good at.

BS: It worked very well. It’s different in soundtrack terms because it started with us talking to a producer about a specific film but that fell away and we were creating our own soundtrack to our own brief. We did try to keep a certain feeling even when we didn’t have pictures to write to, so we had a vague soundtrack discipline when we came to complete work on it. We had fun. I love writing to picture and the best thing about writing to picture is that you’re forced into creative mode. The nature of working for somebody else stops you fucking around, basically. You’ve got to get something down. But with this one, when the absolute brief disappeared, we were able to have fun, so it was the best of both worlds.

There’s a lot of use of time stretched instruments on the album as well. Were you using that Paul programme that people keep spectralising Justin Bieber with?

GB: Ben was actually writing for that programme, rather than just stretching pieces of music randomly. It might be the first time it’s been done.

BS: We were trying to write bits of music where, if you slowed it down however much, it might add the right kind of harmony or dissonance. It was an odd way of going about things, playing a ukulele at a hundred miles an hour and then seeing what it sounded like pitched down.

GB: It sounded like a woolly mammoth!

Sounds pretty disciplined.

BS: Or just like making some mental collage. Guess work, a lot of trial and error. I very quickly worked out what instruments sounded good. We needed another colour on the record. As much as we were into the synth stuff we knew that if it was a proper soundtrack there would be other colours in there. It was a way of using acoustic instruments and taking them into the synthetic world.

GB: It gives you the same feeling and the same washes as an orchestra but without it being a sound you’ve heard before.

BS: The instruments it worked on best were things like hammer dulcimers, ukuleles and singing really fast…

GB: [suddenly assuming the persona of a middle-eastern terrorist from an 80s James Bond film] AYIYIYIYIYIYI!

I take it you’ll be releasing the unstretched version?

BS: Cut to a Czechoslovakian cartoon.

So, as the Keeper of the Comics Faith, were there any moments when Geoff turned round and said, ‘I’m sorry, mate, that doesn’t sound 2000AD enough’?

BS: The thing we were really disciplined about, and Geoff was always on this, was the synths. They’ve become a tool of dance music and you can very easily slip into the dance music world.

GB: You just open the filter a little bit too far and then, all of a sudden, it’s dance music. I don’t want to sound like a synth snob, it’s not that. It’s just I don’t see Mega-City One as being all dancey and ripping, you know? More dirty and heavy.

I notice that Beak> [Geoff’s psych/kraut/groove side project] are on there as well?

GB: When we were working on the film project there were certain elements in certain scenes that it felt right that Beak> should do. It’s psychedelic, discordant music, it did seem like the kind of music you’d get at some crazed Mega-City One party. That’s why this record is an individual take. Especially after… who did ‘I am the Law’?

Anthrax.

GB: A lot of people have got a very tight rock feeling with Dredd and Mega-City One. Proper riffs. I don’t really know how it works, but I totally understand that. That’s how they see it. But when I read 2000AD it was the time of Assault On Precinct 13 and Escape From New York, and also people like Public Enemy.

BS: And cheesy pop culture stuff. Knight Rider! What’s starting to strike me, reading the comics, is the weird stuff that happens with the timeline. It’s a character from the 1970s but set however many years to come. With the music there’s a nostalgic element but also a futuristic element and it sort of felt right.

Drokk is out now on Invada Records