Photo credit: Devo Archives

Most bands engage in self-mythologizing to some extent, but few can claim to have pursued the process to such a singular degree as Ohio’s Devo. Formed by Mark Mothersbaugh and Gerald Casale, two Kent State University students who “shared a love of rubber masks, novelties, kitsch ephemera, sexual fetish magazines and quack religious booklets,” Devo was a well-defined aesthetic before it became a band.

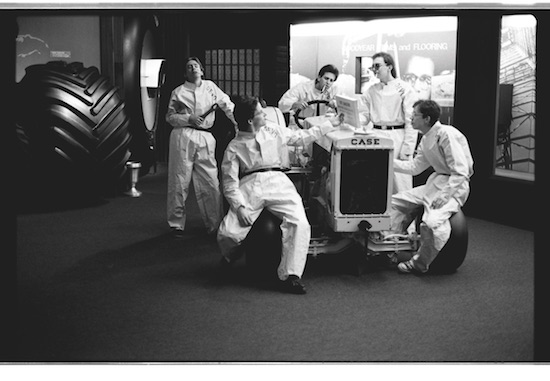

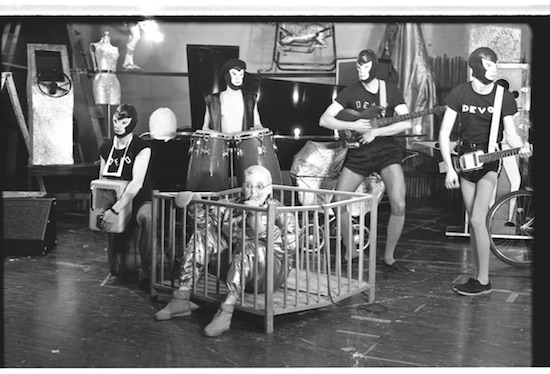

Playing in its first incarnation as Sextet Devo in 1973 at the university’s performing arts festival, early shows were often antagonistic in the extreme, railing against disillusion with “everything we’d been promised by post-bomb culture” and the grim industrial surroundings of Ohio itself. Born out of a collision of ideas scavenged from comic books, religious pamphlets, and B Movies such as 1932’s Island Of Lost Souls, the theory of De-Evolution posited that mankind was regressing, instead of evolving. This was a notion that Mothersbaugh and Casale thought could possibly explain the dysfunctional herd mentality they saw taking hold of American society. According to Casale: “We didn’t want to be right… we thought it was ridiculous… [but not] any more ridiculous than the version of reality we’re fed by priests and teachers.” Early exponents of self-modified instruments, DIY recording techniques, and music videos long before the birth of MTV, the devolved musical form the theory took was perfectly captured in their bizarre debut film, 1976’s The Beginning Was The End: The Truth About De-Evolution.

Over time, the group’s increasingly honed live act brought them to a wider audience, attracting endorsement from the likes of David Bowie, Brian Eno, and Neil Young, and eventual commercial success. Kurt Cobain once said: “Of all the bands who came from the underground and actually made it in the mainstream, Devo is the most challenging and subversive.” Whilst self-confessed “XL fan… since high school” Henry Rollins stated, in typically didactic fashion: “There are two kinds of people: those who get Devo, and those who don’t.”

Despite successfully deploying more ideas during their career than most bands ever conceive of, for some the fine line that Devo walked between satire and self-assurance tarred them forever with the label of ‘novelty act.’ The publication of two books examining the band’s creative process and trajectory, cast much positive light on the band, who continued to perform sporadically in the late 90s and returned with a new album, Something For Everybody in 2010.

Playing at the Vancouver Winter Olympics that same year, and to welcoming crowds at festivals such as Lollapalooza and Primavera, Devo seemed to have returned to a world they had prophesied many decades earlier. Something For Everybody took their simultaneous satirisation and utilisation of the psychological tools of the advertising industry to it’s logical conclusion by hiring the Mother creative agency to direct the campaign, much to the discomfort and confusion of record label, Warner Bros.

Whilst 2003s Are We Not Men? We Are Devo! by Jade Dellinger and David Giffels offered the band’s history as an entertaining biographical narrative, and 2013s Recombo DNA by Kevin C Smith provided a detailed analysis of the band’s ideology and a much needed cultural context for their music, it has taken until now for an official book, that finally captures the band’s visual aesthetic, to arrive on the scene.

Rocket 88’s DEVO: The Brand/DEVO: Unmasked is a 320 page, rubber bound, glossy collection of rare photographs, music paper clippings, fliers and record artwork, interspersed with recollections from the two Devo founders. The ‘Unmasked’ section contains a number of personal photographs that provide tantalising glimpses into the psyches of Mothersbaugh and Casale.

A beat up Mothersbaugh, concussed from a skateboard incident, smiling as though his black eye and grazed face were a badge of honour in his communion class, conveys a subtle hint of the rebellious humour that he would later cultivate to great effect. Jerry Casale’s Kent State University ID, appearing as his sci-fi alter ego, Protar, likewise does much to convey how integral their playfully dadaist ideas were to their own developing notions of self.

Devo’s satirical stance may have been a pose, but as is becoming increasingly apparent, it was a questing and valid one, rather than a superficial or frivolous response. Which is not to deny the presence of both high and low, both futuristic and primitive in the mix, as Casale states: “We felt like what we were doing was sort of like The Flintstones meets The Jetsons.”

Photo credit: Bobbie Watson Whitaker

The Quietus spoke to Mark Mothersbaugh and Gerald Casale, independently via Skype. Syntactical DNA recombined, for the purposes of this article, by Sean Kitching.

It’s a beautiful art object sort of book. How did the project come about?

Mark Mothersbaugh: The publisher, Rocket 88, approached us. Jerry and I both agreed that it was a fortuitous event because we’d both been archiving things, but that stuff starts to slip away and deteriorate and we thought it would be nice to gather it somewhere and make a document out of it. The splitting of the format into the ‘Unmasked’ and ‘Brand’ sections, was Devo’s idea.

To begin with, we didn’t even think we were a recording band. We thought we were agitprop, or an art movement. We weren’t really expecting our lives to be channelled down this thing that was primarily musical, so it was interesting to see the different changes that happened and talk about that. The idea of having an unmasked, was well, I think that’s what people want to see. They wanna see behind the scenes and they wanna know why things happen.

I really regret the passage of album covers. I mean, now there’s the internet, which is a pretty cool trade off, because there’s so much information you can get from the internet, but when we went to CDs and they got tiny and the artwork became just like a thumbprint, it was no longer a collection of information. We miss that stuff, so it was nice to do that side of it and to get to put some reasons behind why things happened the way they did and how the trajectory of Devo occurred.

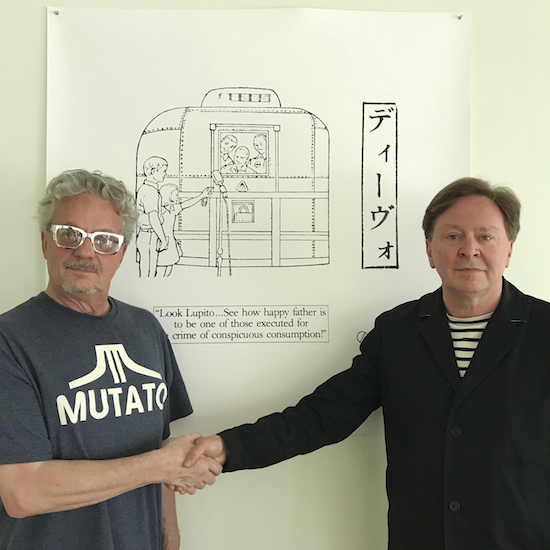

The deluxe edition comes with a signed print. Was there a reason you chose that particular artwork? The caption is very Devo, isn’t it?

MM: That is an image that Jerry and I collaborated on, as purely a fine art project. It was probably the last thing that we collaborated on, before it was all total Devo. It was a very limited amount, like ten, architectural blueprint quality images that were that same size and most of them just got destroyed or lost.

It was because were playing a show in an art gallery in downtown LA, before we had a record deal. We always loved the image and it never got used for anything, and nobody saw it apart from like 30 people at this art gallery, so we resurrected it from the past and did a nice printing of it and signed it and thought that was a good little value added addition.

Gerald Casale: What I liked about that collaboration was, I would often create contexts or narratives and stuff and talk to him about ideas and then he would draw a picture. In this case, he found an image, an illustration that we both laughed at, because we were fond of collecting kind of obtuse, obscure things and things that could be looked at other than in the way they were intended. Immediately I had this caption ready for it – we’ll make this about some people in some sort of Maoist society being punished for conspicuous consumption, rather than kids talking to their astronaut fathers inside this capsule during decontamination.

Photo credit: Hana Blaquera

One of the things that comes across in the book is that you were critiquing the idea of being in a rock band, or a pop band, but you were also complicit in it.

GC: We were totally aware of that. When we said “We’re all Devo,” we were including ourselves. We more or less had prescient knowledge that this would happen to us. That you can’t enter the fray, be in the soup, or go through the corporate meat grinder without it transforming what you do. On the other hand, it’s the only way you have a voice in the market place, so it’s just real, is what it is.

We couldn’t believe, you know, the stupid myth of rebellion that was still going on – that rock bands were dangerous and rebellious. We laughed at that, which is why we said in our press releases: “Rebellion is obsolete in corporate society.”

Mark I and I were very different but there was an underlying agreement on our world view, and we hated the same stuff. That’s always important when you’re young. Mark loved everything we told him about De-Evolution. He jumped in and the two of us agreed, from jamming twice, that we would not do the music we were previously doing. He would never do these progressive rock covers again and I would never do the blues again, but we would sit down and do something original, and as soon as it sounded like anything you’ve already heard, we had the right to tell the other one to stop it. We made that a rule, jokingly among ourselves, and we pretty much stuck to it, and this is how the Devo cannon of songs came about, between 1974, and when we erupted onto the world stage in 1978.

We were spending untold time in basements and garages, day in and day out, working these things out, and working out how to think, how to move, how to dress. We were creating a complete reality – branding, when there was no word for that – we were doing the job of advertising executives. It was a complete concept.

Can you talk about some of the strands of ideas that went into forming the Devo aesthetic, before you were a band?

MM: We were just trying to find out what was really happening in our world, what we were really seeing. We decided that what we were observing was De-Evolution. We collected all sorts of quack theories and we were interested in all the conspiracy theories. We liked alternate information and we were never really happy with science or faith. We thought they both lacked something.

We found different things, like religious pamphlets that were reactionary to evolution and they were kind of hilarious in a way. I found this little pamphlet called Jocko-Homo: Heavenbound [by BH Shadduck] and it was just attacking evolution, to the point where it was really humorous and interesting. Then Jerry found this book called The Beginning Was The End – How Man Came Into Being Through Cannibalism[by Oscar Kiss Maerth] and that really was intriguing to both of us – the idea that humans were not the centre of the universe, that maybe humans were the unnatural species on the planet. We were the species that was insane, and was out of touch with nature, and was destroying everything. We thought that concept was a pretty good explanation for what we were observing, in the news and around us.

We had this idea we were going to make films, a TV network called Devo-Vision, where we would share the good news of things falling apart and we kind of got sent down this road of being a band. We tried not to be a rock band, but we were in those venues. We just wanted an arena to talk about humans and how they related to each other and to the rest of the world.

GC: I know I’ve said this many times in the past, but witnessing the Kent State Shootings on May 4 1970, changed me. I was one way before that day on campus, standing there about 30 yards from the National Guard with their M1 rifles, and then I was another way after they shot. Until then I was pretty much a live and let live, somewhat pretentiously intellectual hippy.

I was doing all the graphics for the SDS – Students for a Democratic Society – of which I was a member. That day we were protesting the expansion of the war into Vietnam by Richard Nixon, without an act of congress. We found it to be an unconstitutional act, and an escalation of an unjust war. He had done it over the weekend, then on Monday morning, about 3000 people gathered on the commons and rang the bell.

It was kind of a ritual. If you were going to do a protest, that’s what you did. We gathered, and the National Guard was ready for us. The plan between the governor and the Dean of the university was that they would immediately announce that there was martial law on campus. Martial law suspends your first amendment rights, meaning you now must disperse. So, as soon as we didn’t disperse, that gave them open season on students. That’s why there were never any prosecutions of the shooting and wounding of students. Four were dead, nine more were wounded, and two of those were paralysed by bullets in the spine, and they got away with it.

It was mind blowing. It was no more mr nice guy for me. Now I realised that I was one of those guys, when you read about Plato’s allegory of the Cave, I’d been in the Cave, looking at shadows. I had bought into the American dream on some sort of level and the idea of material progress and that kind of bourgeois reality.

My friends were actually encouraging me to join the Weather Underground – who were the students who were militarised by this action – but I knew there were only two outcomes to that: jail or death. I was probably too chickenshit for that, but I was committed from that time on to make my art my aggression, to those people who were the illegitimate authority who were destroying democracy and keeping people down. All the voter suppression, the racism, the military spending, imperialism, it really is all just one big gestalt.

When you came over to the UK after a long break, in 2007, I remember Jerry saying: “We warned you De-Evolution was real.” Maybe you were right after all, although I expect you didn’t want to be.

MM: No, no. We were hoping we were just paranoid. We would have loved people to have gone “you know what, you’re right, this is a bad direction we’re heading in.” We would have loved to see things get straightened out. But I think they’re more devolved than they were back in 1974, when we first were talking about it. It’s a pretty crazy place, this planet.

GC: Well, artists tend to be idealists and naive, even when they don’t think they’re naive. They see the good end of something, the good possibilities. It’s like scientists who believed nuclear energy would transform the way the world would be powered, and the first thing we get is a bomb. Because who’s paying for it? The military.

Your early demos, that saw release as Hardcore Devo Vol 1, are often startlingly electronic sounding to those who are unfamiliar with them. Why did the sound change so much by the time of the debut album? Was this largely Brian Eno’s doing?

MM: The early stuff, I was the engineer, and I didn’t know that much about engineering [laughs].

In the early Devo days, my brother, Jim Mothersbaugh, used to modify all of our gear, everybody’s guitars, foot pedals, synthesisers, even his drums. He was the first drummer and his first drum set, he put acoustic guitar pick ups on a drum kit and put those through wah wah pedals and distortion boxes and had an amp onstage. It was terribly noisy but it sounded amazing. That’s the sound that you’re hearing on the first Devo film.

I don’t think it’s super important what the instrumentation was, it was always the ideas behind it – the intention. Live, we had two guitar players and Jerry played bass for most of the music, and I think our live show was more successful than a lot of our recordings.

I’d love to let Brian Eno take the first album and remix it, in the way he intended, because there are a lot of tracks that were recorded with David Bowie and Brian Eno singing back ups, playing instruments on the records. Moebius played on one of the tracks.

There were tracks that Brian added on after Devo went home at the end of the day. He would stay there and experiment with the tracks and I kind of wonder what it would have sounded like if we would have let him have total control of that. Instead he was like a really good patron saint and he guided us through our paranoias and our limited knowledge of recording studios and we came up with something that’s pretty good.

GC: Well you know, those tracks do exist and we could do that any time if you are serious, but that’s mostly apocryphal, there were hardly any things like that going on. We had lived with these songs between five and two years. None of them were newer than two years old before we recorded them. We also had a very worked out, intentional aesthetic that was coming from industrial brutalism in the Midwest, so when Eno started trying to make it pretty, and adding these beautiful harmonies, it didn’t make sense to us. And when I say us, it wasn’t just me, Mark was there pulling the faders down and making sure that stuff wasn’t going into the mix.

It flummoxed Eno alright, because he’s a great artist and we respected him, but he had moved on from the guy that we loved in Roxy Music who was outrageous. He’d become a practitioner of Zen and he’d made the oblique strategies cards, and he’d started doing that kind of ambient airport music and things like that. So he was in this spiritual Zen phase, and we were in this brutal like fuck-the-world phase, and it wasn’t really coming together on a mix level.

Talking about other famous musicians, it reminds me of the ridiculous suggestion at one point that John Lydon become your singer, from Virgin Records’ Richard Branson. It’s so funny to think that he thought you would respond positively to that idea – especially since he pitched it to Mark, your singer!

GC: He thought it was a brilliant idea and he hatched it on Bob and Mark, because they agreed to go meet him in Jamaica. I wanted nothing to do with Richard at that point, because he had caused a lot of trouble with Warner Bros by sticking his hands in the mix when we had a right of first refusal worldwide with them, and had been working on that deal for a year.

I knew what the deal was, Brian Eno knew what the deal was, we knew what we’d get – it was a very good, very fair deal – and Richard, like the devil, or something out of Pinocchio, he dangled things that were not realistic and he was never going to have to deliver on, and got more than half the band to go with it. So, when he drew ‘em down there, we had already been injuncted, the album had to wait till August, instead of come out in May, and Warner Bros had half the world and he had half the world.

He had Johnny Rotten in one of the hotel rooms, in the place where he put up Bob and Mark and he had and NME or Melody Maker, reporter and photographer, in another room and he had planned to just hatch this on Mark, thinking he’d go for it, and then take pictures of Mark and Johnny together.

He gets them high on really strong Jamaican weed, and then he lays it on them. Bob and Mark said they started laughing, thinking he was joking, and then they could see by his face that he was upset, and then he said: “no, I’m serious. Johnny Rotten is nearby in another room and is ready to come over and talk about this.”

In fact, we had seen the Sex Pistols’ final gig, at Winterland in San Francisco. We were there and watched it all completely devolve into chaos, with fights right onstage. Sid Vicious was bleeding, and he threw the bass guitar down and left. Then they played three or four songs with no bass.

How did it feel to discover that Iggy Pop, David Bowie, and Neil Young appreciated what you were doing? The film of Devo and Neil Young doing ‘Hey Hey My My,’ is a great clip.

GC: I know. You have to understand what it was like to be operating in like a boy in a bubble situation in Akron, Ohio, where no one cared about you. If people knew what you were doing, they either made fun of you, or felt sorry for you. Some people wanted to beat you up, and it was all going nowhere for a long time and I was doing every last thing I could do and think of, and using every last connection I had in the real world to move Devo to critical mass, get it up on the radar and make it good enough that when we played, you didn’t have to explain it to people. That took a while. So that, overnight, you go from being shunned, or ignored, to suddenly some of your most influential heroes and people you respect, responding to you.

I mean, every artist wishes that would happen. You really don’t care what a bunch of idiots in a club think, and especially if they’re awful people, you kind of get off on pissing them off with your music. You got off on them threatening you and throwing beer bottles at you, but you don’t want David Bowie to dismiss you, or say something nasty in the press. You don’t want Brian Eno to do that. You don’t want Iggy Pop to go “these guys aren’t rock and roll.” You certainly don’t want Neil Young to go “what the hell is this shit?”

So suddenly, all those different people were coming around, saying “this is brilliant, you guys are great.” It wasn’t coming from some manager or label, connecting us up and telling them what to say, to get a producing job or something like that, it was real, and it was all happening in this tight, little six month period.

For me, it was like I felt, “yes, this is what I’ve been working so hard for, for four years now, this is what I expect.” Then the other half was like “I never really believed this could happen.”

This must have been a big learning curve for you, taking on the role of manager for the band at the beginning.

GC: Yeah, I had been doing all that, and avoiding all the pitfalls and that’s how we got to a point, where we had a production deal with Warners, where we control the money. You know, with a lot of bands, they’ll say, they’re signed for $1.2m – but the record company is controlling all the money. So, they put you in a studio and pretty soon you get this bill for 500 grand, plus a producer and they’ve spent all your money and you have to pay them back from your sales.

Well, we could pick the studio, and the rate. We could pick a producer and we could control our money. We had final say creatively over any graphics, album cover, posters, any promotion. We used t-shirt promotion money to create those videos, because they didn’t understand what we were doing. They just thought we were a stupid art band, and why didn’t we want t-shirts in the record stores? Why were we going to spend it on some weird little 16mm film we were making?

That’s how we made ‘Come Back Jonee’ and ‘Satisfaction’ and ‘The Day My Baby Gave Me A Surprise,’ all for ridiculously low amounts of money – $2,000, $5,000. It was DIY.

We had five music videos done when MTV came into existence, so we were suddenly heroes, because they had no programming. They had one David Bowie video and one Rod Stewart video and the Buggles video, and five Devo videos. Then the Vapors came out, and they had like ten things they were rotating all day long, and we were getting nationally famous.

People often forget about the whole video component to Devo, which was part and parcel integrated into the concept from day one. We thought we were going to make short films and put them out on laser disc, not record albums. We thought our new songs would drive a narrative, that was a Devo story, and we’d put out one every year, because we believed in all the positive tech propaganda from Popular Mechanics and hifi stereo magazines that laser discs were imminent, in 1974 [laughs]. And you saw what happened to that. Another case of the idea versus the real. Three companies going after each other, they ruined that idea.

You took a break for a while and then you started playing again. Did you feel that the attitude of audiences and other musicians that you had inspired had changed and vindicated you? It seemed as though you were very much welcomed back.

MM: Yeah, there was a different kind of energy, and there’s no way around that. That’s the way it is with everything. You can’t be brand new every year. People like David Bowie – and Devo even – tried to reinvent ourselves with every album, but at a certain point, that becomes what you are anyhow, so you can’t be the next shocking thing if you were already the shocking thing ten years ago.

Personally, of all the people in the band, I love creating music more than I do performing it, so I’m the one who’s always dragging my feet if we’re talking about doing another tour or something.

GC: Devo had long since ended being a polarising aesthetic, where you were going to get beat up for wearing a Devo t-shirt, because the fact is, and I think you would agree, De-evolution is real, and by that point everybody had started to figure that out, it wasn’t even an art pose anymore.

At that point, I started saying this in interviews, jokingly, that we were the house band on the Titanic, because as Western society self-destructs, the pose we had struck, and the satirical warnings we had put out, had all come true. So now it was like going back and listening to the band that had your favourite song at the Prom, or the song that you got married to, there was that familiarity.

I think that’s happened in spades now because of what started happening around the mid-2000s with the internet and YouTube, and a whole new generation discovering Devo, so that we were like the new wave version of the Gratetful Dead. Our concerts would have three generations of people out there – the people who grew up with us, their sons and daughters, and their sons and daughters or relatives there. You could see it in the audience and you could see it in the after show meet and greets. In other words, you couldn’t kill Devo. Even though our footprint in the marketplace had been scrunched down, it was still there, because there’s a kernel of validity to what we did that’s got nothing to do with meaningless style.

Devo was a gun to the head in terms of art and we looked foolish to people, we looked like Dada clowns. There’s nothing hip about the yellow suit – there never will be – that’s why we wore it. Plus it was disposable, so it was cheap.

Credit: Bobbie Watson Whitaker

When you were recording Something For Everybody, it looked like you took your idea of using the tools that pop groups usually use in a transparent and satirical way to its ultimate extreme. There’s that hilarious picture where one of the band is holding a baby, and you have an audience member from every possible spectrum of the demographic.

MM: That was interesting, because that became something that made Warner Bros panic a little bit. It was not something that they were used to from a band at all. That was the most foreign idea that they’d ever heard and it even felt to them like we were impinging on their territory, and you know, of course we were.

It was a good concept, we just weren’t supported in it. Once they’d figured out what we were doing, the record company had more worries about it than excited expectations. Which is kind of perfect.

GC: Given the implosion of the record business over the last 10 years, beginning in the new millennium, it seemed to me that their most significant value to an artist was the ability to market and publicise the creative content. However, ad agencies are far more effective than record labels at doing that because they have the best talent and that’s what they do every day.

I approached creative director, Paul Malmstrom, at the Mother agency in NYC about creating a marketing campaign for Devo. I had worked with him over the years, directing a number of his TV spots. We agreed on a concept that was completely in sync with Devo’s ability to satirise and celebrate at the same time. Namely a campaign based upon skewering ad campaigns and the techniques they use including focus groups, song studies, reality TV segments, viral internet bits and billboards that create confusion and mass reaction.

We presented the idea to Warners in a full on agency pitch. All of their executives signed off on it but then the pushback started as soon as Mother began to implement the dada style components. Things came to a head when Mother produced a 5 part ‘reality’ series using actors as ad executives, record company executives and the real members of Devo in power point type presentations where we made fun of ourselves for being involved with an ad agency as well as making fun of ad agencies and record labels.

They couldn’t divorce themselves from the equal opportunity spoof and felt offended by the humour. It all began to unravel since they held the purse strings to the marketing budget as per contract. It went downhill from there and Mother and Devo were crestfallen.

The label had no plan to approach radio and were hoping merely to skate by re-issuing Devo’s back catalogue and getting revenue based on Devo’s live shows from our 360 degree deal with them.

The whole mess was happening in the midst of the biggest US economic crisis since the Great Depression. Warners itself was imploding as top executives were jumping ship. Bottom line, they second guessed themselves on a fantastic Devo / Mother collaboration and in addition really failed to bring Something For Everybody to market.

Mark, just before this interview, I saw some video footage of your orchestrions. The look beautiful, what are they?

MM: I’ve always been into modifying and experimenting with gear. Now I’ve done 200 films [including Thor: Ragnarok] and TV series, I get to come over to Abbey Road, once or twice a year and record the London Symphony Orchestra playing on a film track, but I was still looking for something that I wasn’t getting from using electronics or acoustic instruments, and that was making these instruments out of bird calls and different sound making devices. Even old organ pipes and tuning doorbells, so you could play chords with doorbells and things like that. It just gave me another way to think, to step outside of the box.

I love making these. I have one I just finished that has 18 hundred-year-old foghorns that you squeeze with a bellow. I tuned them so I have 18 notes and they sound really good. I love messing around with them. And they’re all mechanically controlled instruments, not electronic. There’s different museums that have them. In fact, one of them is going into the Computer History Museum in Sunnyvale [in Mountain View, California]. They have an amazing collection of computers, dating back to even when computers were mechanical, hundreds of years ago, before they even started making electronic computers.

Jerry, I read that you have a vineyard now. How is your winemaking progressing?

GC: I’m making small production, I’m getting good reviews. I like it, and anyone who tastes it really likes it. I’m making pinot noir and I”m making a rosé of pinot noir, and I’m about to make a very strange thing, that hardly anybody’s doing, kind of an albino pinot noir, where you take the juice away from the skin. It never turns pink or red, it stays white and tastes beautifully dry yet floral. I’m going to call that sans pinot. You can go to the site and check it out. It’s called fifty by fifty wines, after an unfinished architectural design by the 20th Century Modernist architect, Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, which will be the heart of the estate when it’s completed.

You have a show in Texas on the 8 August, are there any more shows planned?

MM: I don’t think we have any more shows planned until probably about two years from now, perhaps 2020. We’ll do one last tour maybe, but it will give us enough time ahead of that to give people a chance to work us into their schedules. This’ll be kind of like the stick a fork in it, we’re done tour [laughs].

GC: Mark knows that everybody else is suited up, boots on, ready to go anywhere, anytime, because without him, the promoters won’t let us do it. So if he says yes, it’s done.

DEVO: The Brand/DEVO: Unmasked is published by Rocket88