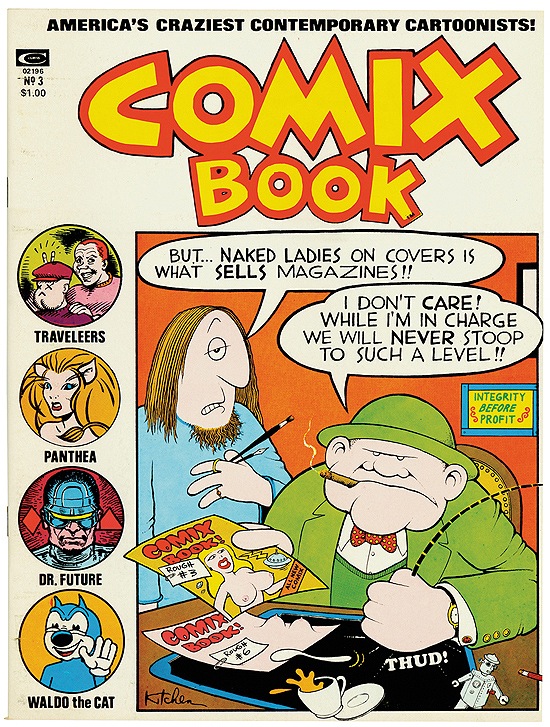

In his introduction to the newly released The Best Of Comix Book, Stan Lee calls the whole experiment "one of the most courageous things I’ve ever done – editorially". And bizarre as it may sound, from October 1974 to March 1975, Marvel Comics did indeed publish three issues of an underground comicbook, Comix Book. The whole fascinating history is recounted in James Vance’s twenty-page opening essay, after which the book’s paper stock switches to ‘the closest thing to newsprint we could get’ for the actual comix. They were, after all, originally published on newsprint. Let it never be said that Denis Kitchen and John Lind don’t have keen eyes for detail and design. The book itself is an impressive piece to behold.

Kitchen, underground publishing legend and very talented artist in his own right, spearheaded the whole Comix Book project, which allowed him the finances to keep his own Kitchen Sink Press up and running. And Kitchen Sink would publish the further two issues that were ready to go when Marvel pulled the plug. Collected for the very first time, The Best Of Comix Book showcases stories by the top underground talent of the early 70’s. Featuring John Pound’s hilarious ‘Flip The Bird!’, Trina Robbins’ tale of a half-woman, half-lion who gets mixed up in rock n’ roll and international intrigue, ‘Panthea’, the three page ‘Maus’ (originally created for Funny Animals and here given its first mainstream exposure, Art Spiegelman would later expand the idea to win a Pulitzer Prize), and plenty more from the likes of Kim Deitch, Basil Wolverton, Skip Williamson, S. Clay Wilson, Harvey Pekar & Robert Armstrong, Howard Cruse, and as much perversity as a lot of these artists thought they could get away with.

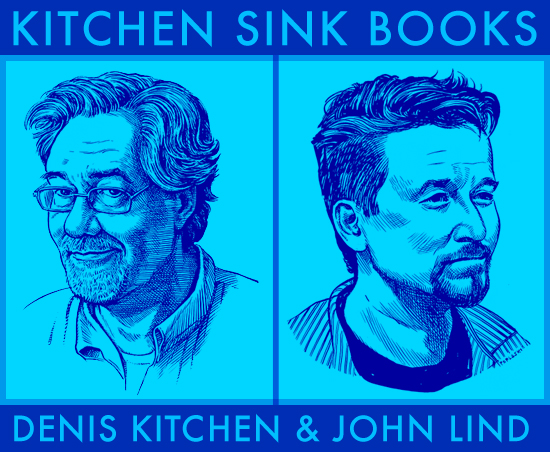

For a number of years now, Kitchen has been collaborating with designer John Lind on various ventures, including such excellent, comprehensive books as The Art Of Harvey Kurtzman and The Oddly Compelling Art of Denis Kitchen. I caught up with Denis & John in Amherst, Massachusetts to talk about their new enterprise, Comix Book, aesthetics, and jukebox collecting.

Denis Kitchen, John Lind, drawn by Peter Poplaski, 2014

Denis Kitchen: Our new imprint is from Dark Horse Comics and it is called Kitchen Sink Books. The name is obviously inspired by my original Kitchen Sink Press that published from 1969 until 1999. John and I have been working together packaging books as Kitchen, Lind & Associates for several years, assembling art books for a number of top publishers, mostly outside comics. While we’ve worked with some great people in the book industry over the past decade, it isn’t always satisfying. There are a number of committees and approvals over the look and content of the final product that were starting to affect our workflow, and honestly, our reason for still wanting to create books in the first place.

So, we’d been talking for some time about a situation in which we’d have more creative control and felt the only way we could realistically do that is our own imprint. We had also discussed basing the imprint in the comics industry specifically, which allows us to return to our roots, so to speak. Mike Richardson and Dark Horse Comics were the ideal match. Mike and I have known each other for decades and he was aware of KLA’s abilities and vision for the projects we want to produce. Dark Horse announced our imprint this past July, and The Best of Comix Book: When Marvel Went Underground was the first official title, published in December 2013. The next few books have been shuffled a bit due to distribution [Dark Horse signed with Random House for book trade distribution in late 2013], but will pick up a regular schedule in late 2014.

How did you two meet?

John Lind: My "past career" in comics was as the Project Development Coordinator for Kevin Eastman’s Words & Pictures Museum, which was a relatively large museum devoted to comic book art located in Northampton, Massachusetts. Kevin built it after the success of his Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, which ironically also lured Kitchen Sink Press to the area. My job included coordinating a lot of the book signings and lecture events, so we met casually around then.

For context, you’d need to understand the microcosm of the comics industry that Northampton was at that time. It had a large core group of comics people—Words & Pictures, Tundra, Kitchen Sink Press, Xeric Foundation, Mirage Studios, which are all the Ninja Turtle guys . . .

DK: . . . and the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

JL: Right. This was the mid ’90s, and over that decade, I’d estimate at least a hundred comic book professionals lived or worked in Northampton. Not only creators—of which there were many—but editors, designers, sales staff, and office staff for the various companies. There were creators who lived in the area like Scott McCloud, Al Columbia, and Michael Zulli, and then the ones who stayed for a time to work on projects or just extended visits, like Neil Gaiman, Dave Sim, and Rick Veitch. It was one of the few clusters of comics professionals in the country outside of NYC.

Anyway, flash forward a few years and I was working as a book designer when Denis hired me to work with him on a few projects. We hit it off and a few years later formed our packaging house, Kitchen, Lind & Associates, and have been assembling projects consistently since then. We have a shared aesthetic view of design; specifically what we find appealing in comics. Since I basically grew up reading Kitchen Sink and Dark Horse comics, I’m sure it influenced my sense of design and my taste in comics so it’s probably been somewhat of a natural progression into this for me.

Would you like to say anything about your aesthetic sense?

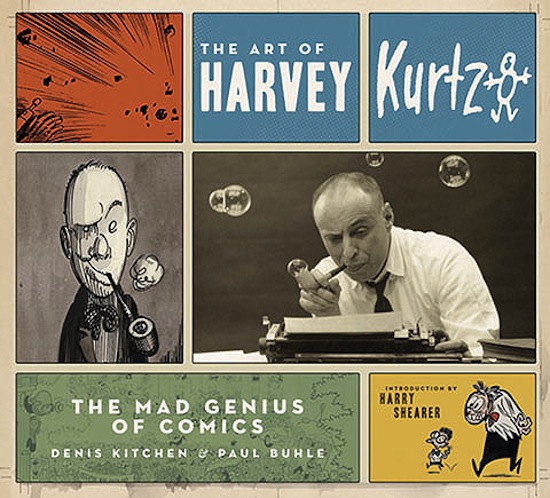

JL: The Art of Harvey Kurtzman (Abrams ComicArts, 2009) is probably one of the most well-known books we’ve done, as it won an Eisner, a Harvey Award, and an American Design Award in 2010. Our combined sense of aesthetics and design went full force into that book. Add to that going through and selecting all the images from the massive amount available in the Kurtzman archives. We found that we mesh well together when choosing the content for books as well as the general look and the subject matter. I’m also very conscious when designing of not overshadowing the work—I think this is something that is valued and expected by the creators we work with. I’m good at absorbing styles and understanding them in order to work around the contents of a project.

Now at Dark Horse, Mike Richardson shares a similar aesthetic and background in his early years as Denis and I do (he was a designer originally). Mike also cares deeply about the history of comics—it is something he’s obviously passionate about and he understands that some of our projects may not be bestsellers but will ultimately be historically valuable to the industry to have in print. He’s been very supportive of any book proposals and projects that we’ve discussed . . .

DK: And I would just add that’s a pretty rare thing—publishing in general is a bottom line industry and it isn’t one where aesthetics alone or the inherent value of a project is enough for most publishers. When I started not all that many decades ago, it was a more genteel business. The big New York publishers were run by editors who were very literary, erudite people, and decisions were largely based on a project’s merit. These days most large publishing companies are corporations owned by conglomerates and run by bean counters. It’s not the same business. With Dark Horse, we’re thrilled to have our autonomy and the full support of Mike, who is the sole owner.

JL: Right, and that said, there will be some surprising books from our imprint that we anticipate will be popular among fans and probably impress those paying attention. Think of the imprint as a hybrid of the best Kitchen Sink Press had to offer, mixed with classic Dark Horse and taking a big cue from the sort of books we were packaging for Abrams, Chronicle Books, Hyperion, etc.

DK: Also, as John said, The Art of Kurtzman set the pace for us with what we like to achieve and the way we’d ideally like to work. Kurtzman is not a household name, but obviously he needs to be kept in print. The cognoscenti know who he is, but to use a musical analogy, he ought to be recognised like a Jimi Hendrix or a Lou Reed, someone whose work is always out there and it’s always being rediscovered. So the key to that is to make it available. To us, Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book in a comics store should be like finding Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in a regular bookstore. You should always be able to find copies.

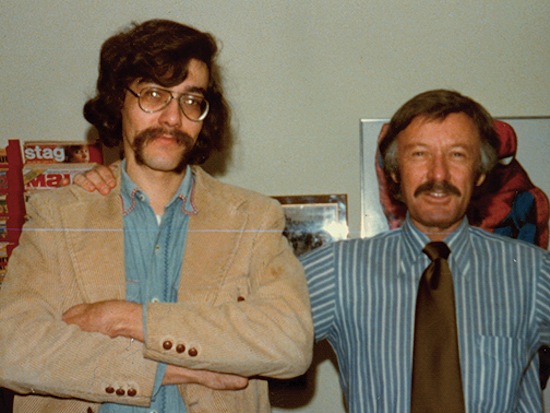

Denis Kitchen & Stan Lee, NYC, 1974

So what was the impetus to actually put out a Best Of Comix Book in 2013?

DK: Well, first, the material has never been collected. And it was the fortieth anniversary and there are some great comix in there. I’ve stayed in touch periodically with Stan Lee over the years, and he’s always been a gentleman and very supportive. I casually mentioned this collection to him and he was very enthusiastic. In an odd way, he’s quite fond of it—he wrote the introduction and signed a limited number of copies in fact.

Until the collection, I hadn’t reread this material in quite a long time and I was a little surprised myself how much was slipped into it. It wasn’t always blatant but there was some pretty graphic nudity and obscenities . . .

JL: Yeah, you got away with some impressive stuff for publishing under the rules Marvel had outlined for you. I was very surprised the first time I read through them.

DK: And just the fact that, as John has mentioned more than once, Marvel sent cheques to S. Clay Wilson! How unusual is that concept? [laughs]

JL: That was the really mind-boggling thought for me—Stan Lee literally signing a cheque to S. Clay Wilson, arguably the most depraved of the underground cartoonists, for his somewhat restrained comic to be published by Marvel . . .

DK: I think, honestly, that most people at Marvel found this stuff so ugly or repellent in some way that they literally didn’t look at it. [laughs]

I’m probably a little too close to it, but John has pointed out to me that in some way Comix Book really did help change our industry. It was the first time a large company like Marvel was forced to recognise creative rights, and the first time Marvel returned art. It was also the first time Marvel allowed creatives to retain copyright. Those factors became a Pandora’s box— once opened, they were difficult to put back. As a result, in subsequent years, Marvel and DC and the other majors were forced to treat artists on more equitable terms. The undergrounds of course were always run in an economically fair way with copyrights and art being returned. That was a given. Stan was unusually open to the idea of this being an experimental project and that maybe he could bend the rules a little bit. But the old timers who worked for Marvel looked at it and said ‘why are you giving these long-haired kids stuff you aren’t giving us?’ So there was grousing. And that’s dangerous for any company.

Also, on a personal level, the context of me doing it at the time was frankly one of economic desperation. 1973 was an awful year for underground comics, with the double whammy of a Supreme Court censorship decision and a glut in the marketplace, which for us was primarily head shops. Since undergrounds sold on a non-returnable basis and most of the head shops were not savvy about ordering comics, they’d order about a dozen of each and some dozens wouldn’t sell. So when their comic racks were stuffed full, a number of retailers just said, ‘Alright, we’re not ordering more until we sell what we have.’ The combination made our sales plummet and things looked dismal. I had been in touch with Stan for a few years and at some point he made an offer of ‘Hey, why don’t you come and work for Marvel,’ and I said, ‘Alright, let’s talk.’

Even though I grew up loving Marvel Comics, I didn’t really want to work for "the man" and I didn’t want to move to New York City. I was enjoying what I was doing and I knew that what we had in underground comics was an extremely rare thing. That total freedom we had, the fact that I was running my own company, I didn’t want to give that up. So what I was able to do—and in hindsight this was remarkable—was to find that place in the middle where I worked part time for Marvel, kept Kitchen Sink going, and Marvel basically subsidised it. So, looking back, I see it in the context of it being something I had to do and because my hands were tied, Comix Book wasn’t the magazine it would’ve ideally been if there were no restrictions. But there were enough highlights and I enjoyed working with Stan, so I’m not ashamed of it at all and I’m glad we did it.

JL: Obviously, Comix Book was an important footnote in comics history and one that deserved a nice collection. It is something that fans wouldn’t necessarily know about unless they sought it out. For me, it was one of those titles I would hear about – ‘Denis Kitchen did comics with Marvel, what?’ – but didn’t have a copy of until about the mid-’90s. A couple of the later issues are relatively scarce.

Also, aside from the fascinating back story, which Jim Vance retells in his essay, the comix just had a solid lineup of underground creators who were doing great stuff at the time. S. Clay Wilson, Kim Deitch, Art Spiegelman, Justin Green, Trina, Howard Cruse, Skip Williamson. We felt it needed to be back in print, and Dark Horse agreed.

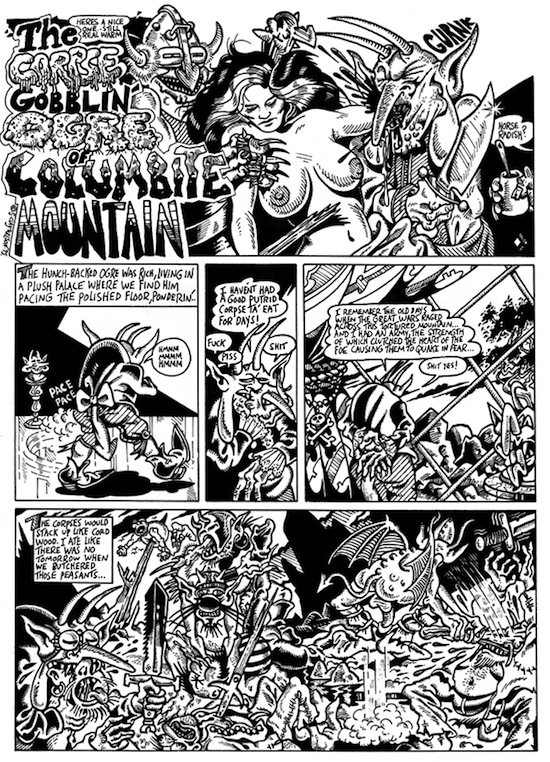

Title page from "The Corpse Gobblin Ogre of Columbite Mountain" by S. Clay Wilson, Comix Book #5.

In one of the letters to Stan Lee included in Comix Book, you mentioned you wanted to do European reprints.

DK: The initial title of Comix Book was to be Comix International, and there were some particular underground European cartoonists who I admired: Joost Swarte, Evert Geradts, Gotlib, and Mandrika specifically. This may have been pre-Moebius. There were creators over there who I thought deserved exposure to a larger American audience.

I did publish some of the later European work in underground comics. We ended up doing an all-Dutch issue called ‘Dutch Treat’ with about half a dozen of those guys. I would’ve loved to have done more but it was a little too obscure, and in retrospect the translation was probably a little bit stiff. But again, it was impulsive, and I’m glad we did it. We also published a series of three issues called ‘French Ticklers’ and Moebius contributed to that . . .

JL: ‘French Ticklers’—that’s an unmistakable Denis Kitchen title. [laughs]

How did you find out about these guys?

DK: Initially, it was Harvey Kurtzman who turned me on to them. Harvey had a real fan base among the French cartoonists, and magazines like Fluide Glacial and Métal Hurlant had put him on their mailing list. He would often pass them on to me and say, ‘You don’t have to read French; this guy’s work is funny just looking at it.’ And he was right, it was just inherently funny. The artist Edika is one example I recall. He was outrageous. Very vulgar stuff but hilarious. A handful of European creators visited me when I lived in the middle of Wisconsin in the early ’70s. There was a buffalo ranch near me and I took them there—they thought it was the Wild West in Wisconsin ’cause they’d never seen a buffalo before! [laughs]

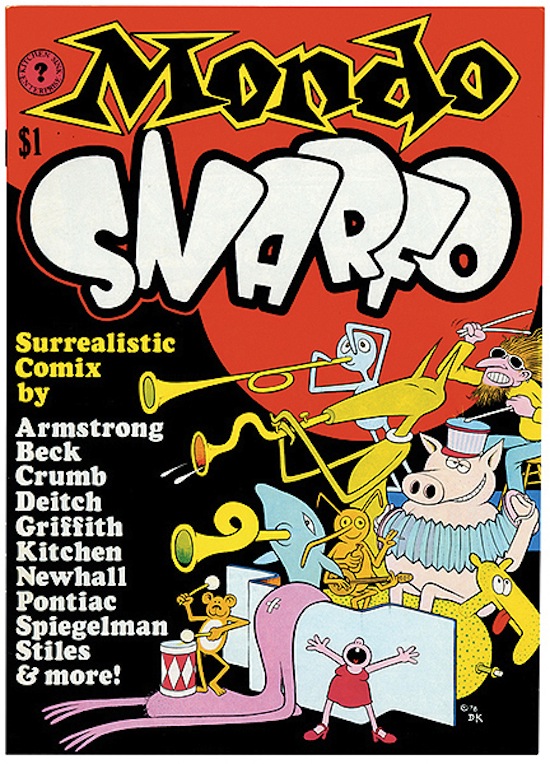

Weird Trips and Mondo Snarfo sound particularly interesting to me. Any plans to reissue those?

DK: I can’t say they’ve been among our initial projects, but I loved doing both. Weird Trips, as the title suggests, was inspired by the hallucinogenic drug era, and the idea was to showcase some of the stranger stories we were aware of directly from the counterculture or culture in general. To me, it was an experiment of mixing text and comics and cartoon illustrations.

Mondo Snarfo was clearly a spin-off of Snarf [a humour series from Kitchen Sink, 1972-1990] and it was what we called the ‘All-Surreal Issue’. I personally love the surreal art movement; it was probably my biggest influence outside of comic books. As far back as grade school, Salvador Dalí and René Magritte appealed to me. The images were just so startling and provocative to me. Growing up, I wasn’t in an artsy community or a family that was into the arts, but I found the surrealists mesmerising. It was inspired by poetry, dreams and non-rational associations, and spoke to me in a way that most other art movements did not. When I was developing my own style, I found there was a natural surreal element to it, an aspect I never completely abandoned. I like to do what I call stream-of-consciousness work, in which I’m using the comics medium and style but I’m not telling a linear story—it’s either spontaneous or nontraditional. I thought there might be some other cartoonists who like to do experimental work too. And almost everyone I connected with said sure – Crumb, Bill Griffith, Wilson, Spiegelman. So that spawned Mondo Snarfo.

The Oddly Compelling Art of Denis Kitchen, what took so long for that to finally come out?

DK: In part, I always felt a little uncomfortable that it would seem like vanity press when Kitchen Sink was going to publish it. It was scheduled for the twentieth anniversary of the company. We had a busy schedule and I had to cut something, so I cut my own book because it seemed too self-serving. Later my marketing director, Jamie Riehle, suggested we do it for the thirtieth anniversary. So it was firmly scheduled again and then the company went out of business just before the thirtieth anniversary. [laughs] Years later, I ran into Diana Schutz from Dark Horse at a convention and she asked, ‘Why isn’t there a collection of your own work?’ I told her that basic story and she replied, ‘Well, Dark Horse will do it.’ Suddenly I felt ‘OK, great, I don’t have to worry about that vanity element anymore.’ John co-edited and designed it, so I had a complete comfort level that allowed me to step aside and not interfere.

JL: I recall ordering that book from Kitchen Sink Press—possibly twice—I definitely preordered from my local comic shop in the early ’90s. After I knew the full story, I think I came to the conclusion that the only way I’d ever get to actually own the book was if I put it together! [laughs]

In Oddly Compelling . . . you mention that certain types of background music are important components of the creative process.

DK: When I’m drawing, I like playing my favourite tunes, which tend to be blues, jazz and popular tunes from the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s. I am very fond of an earlier musical era. There’s a rhythm and bounciness to that music that keeps me invigourated, that makes the tedium of inking go faster. I like to be totally focused with blinders on – just the music and that panel in front of me.

Cover to Fox River Patriot #53, 1979

How did you get into collecting 78s jukeboxes?

DK: I was living in a 2nd floor flat in Milwaukee in 1969 and it was one of those rare moments in my starving days when I actually had money in my pocket that I didn’t know what to do with. I was flipping through the classified ads and noticed somebody had a jukebox for sale for $50. I remember thinking ‘That’d be kind of a cool thing to have.’ So I called and went there. I owned a hearse at the time, a 1954 Cadillac, so I could haul things. The guy had a 78-rpm Wurlitzer juke. It was beautiful. I gave him the money and hauled it upstairs, which wasn’t easy. You lose friends when you collect jukeboxes. [laughs] And then I had to go and find 78s: a lot of good country & western stuff came from my late dad, Hank Williams, Hank Snow, and Bob Wills. But stuff was easy to find then: nobody wanted 78s, so they were a nickel or a dime apiece. And I also inherently just loved the old music and began to discover things.

So, a little later, a collector was visiting me and noticed I had a super rare old Socialist Labour Party jugate button in my button collection. He really coveted it and knew it was valuable. I didn’t want to sell it because it had sentimental value. But then he said, ‘I see you like jukeboxes. I’ll swap you a jukebox for it.’ And suddenly sentiment went out the window. It’s like [incredulous] ‘This little tiny button for a jukebox?’ Done! Then, suddenly—when you have two of something—you’re officially a collector.

At one point I owned close to forty jukeboxes, when I had a big barn in Wisconsin and plenty of room. Now I’m down to my last half dozen because of practical matters. But there’s a beautiful aesthetic to the jukeboxes from the late ’30s to the late ’40s. That was a golden era when the design was at a pinnacle. These were commercial machines that were trying to lure your dimes and quarters. And the way to do that was to be beautiful and have flashy lights and bubble tubes. At a point in the early ’50s when the conversion to 45s became the norm, they really got ugly fast. It was then all about the higher number of plays and the actual aesthetics fell way down on the list.

Did you know Crumb at the point you started collecting jukeboxes?

DK: Yes, I met Crumb in 1970. I already had at least one jukebox the first time he visited me. He was mostly into records, but briefly had one old Seeburg jukebox. He and some friends were hauling it in a pickup truck. That model had a kind of lid that flew off and they didn’t notice it until they were way down the road—so he gave up on jukeboxes. [laughs] But that’s when I had stacks of 78s that I was getting real cheap. He went through my stacks and found a handful that he wanted. He said, ‘What do you want for these?’ and I said, ‘I don’t know. Swap me a piece of art.’ At the moment that seemed fair, but in retrospect I traded him forty cents’ worth of records for a drawing that’s probably now worth a few thousand dollars. But at the time it was just a casual little trade . . .

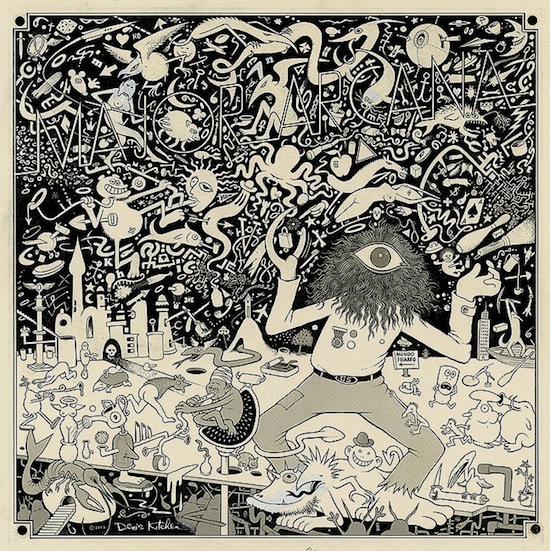

Original to Major Arcana album cover, 1975

A similar trade happened with that Major Arcana album cover, which was the only album cover I ever drew. I did that as a favour to the band and I ended up putting ninety hours into it. I just thought it was a cool thing to do and wanted to do one, so I made it a showpiece. The band felt guilty because they couldn’t afford to pay me, so they gave me a carton of albums when it came out, which I now sell for $300 each to Japanese collectors. The irony is that I did it for nothing, they paid me in what seemed worthless at the time, and it ended up being this cult item in Japan!

But I guess, when you think about it, a lot of what John and I still do is best appreciated by cultish audiences, with the rewards down the road [laughs]. It’s just that now we’re balancing that with broader-based projects too!

The Best Of Comix Book: When Marvel Comics Went Underground is out now published by Kitchen Sink Books and Dark Horse