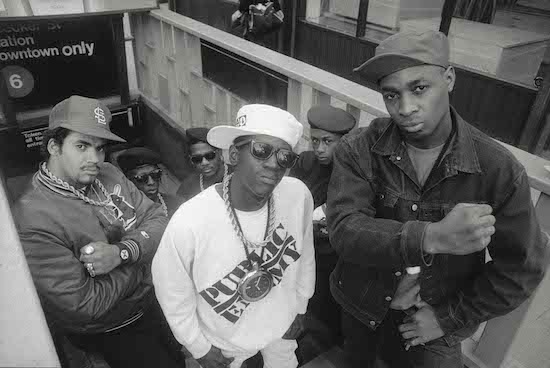

Credit: GLEN E. FRIEDMAN © Photo Public Enemy New York City Early 1987

At the end of the 1980s, it was finally evident that something needed to be done about digital sampling. Hip-hop producers were making money off of the talent and toil of other artists. This would not stand! The Turtles sued De La Soul for $1.7 million, Gilbert O’Sullivan went after Biz Markie, the Beastie Boys spent a quarter of a million dollars clearing samples for their cluttered kaleidoscope, 1989’s Paul’s Boutique. In another case of technology and culture outpacing The Law, the sampling crackdown coincided with the hacker crackdown.

One of the most recognisable cultural contributions of rap music is sampling. In its simplest form, a sample is a piece of previously recorded sound, mechanically lifted from its original context, and arranged into a new composition. In hip-hop, samples were originally manipulated using turntables and vinyl records, but the practice has since largely moved on to more efficient digital samplers. Commerce and copyright laws notwithstanding, anything that has been recorded can be used as a sample (e.g., beats, guitar riffs, bass lines, vocals, horn blasts, etc.). “Using everything from drum pads and samplers to magpie the last few centuries of speeches, music, and commercials and turn them upside-in for the betterment of the practitioner and listener,” emcee and producer Juice Aleem tells me. “Hip-hop is hacking.” Sampling technology allows producers to make new compositions out of old ones, using old outputs as new inputs, like a hacker cobbling together code for a new program or purpose.

The first example of this sort of sound hacking on the Billboard charts was a 1956 song called “The Flying Saucer” by Bill Buchanan and Dickie Goodman. The two collaged clips of songs of the time together on a reel-to-reel magnetic tape recorder creating a ridiculous alien-invasion scenario. Four record labels sued the two composers and lost. The judge deemed their looting a new and original work.

Mining the past for samples and sounds, hip-hop hacks recorded sound for self-expression, and, like cyberpunk, hip-hop has spread around the world. Both are a part of a globalized network culture that decentralizes the human subject’s stability in space and time and in which the technologically mediated subject reforms and remixes ideas of body normativity. With everything from clothes and glasses to tattoos and piercings, technology changes what is considered normal to have on or in your body.

Cybernetics, the science of command-control systems and from hence the “cyber” in “cyberpunk,” defines humans as “information-processing systems whose boundaries are determined by the flow of information.” Technologically reproduced memories disrupt more than just body normativity: media theorist Marshall McLuhan once declared that an individual is a “montage of loosely assembled parts,” and furthermore that when you are on the phone, you don’t have a body. Technology dismembers the body. Our media might be “extensions of ourselves” in McLuhan’s terms, but they’re also prosthetics, amputating parts as they extend them.

Grandmaster Flash once described another DJ as using “his hands like a heart surgeon.” In his book on Public Enemy’s undisputed and sample-heavy classic, 1988’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Christopher R. Weingarten draws a lengthy and effective analogy between records and the body, casting samples as organ transplants. Tales of transplanted organs causing their recipients to adopt the tastes and behaviours of their dead donors read like the “meatspace” anxieties of cyberpunk:

“A 68-year-old woman suddenly craves the favorite foods of her 18-year-old heart donor, a 56-year-old professor gets strange flashes of light in his dreams and learns that his donor was a cop who was shot in the face by a drug dealer. Does a sample on a record work the same way? Can the essence of a hip-hop record be found in the motives, emotions and energies of the artists it samples? Is it likely that something an artist intended 20 years ago will re-emerge anew?”

Conceived as a combination of the hip-hop of Run-DMC and the punk rock of the Clash, Public Enemy emerged from Strong Island, New York in the late 1980s. Made up of emcees Chuck D and Flavor Flav, DJ Terminator X, and Professor Griff and the S1Ws (the Security of the First World), their paramilitary dance squad, P.E. upended not only what hip-hop could be but the power of sound itself. Their production team, the Bomb Squad (Eric “Vietnam” Sadler, brothers Hank and Keith Shocklee, as well as Chuck D) used upwards of forty-eight separate recording tracks to build their apocalyptic collages. Where their 1987 debut, Yo! Bumrush the Show relied on live instrumentation in addition to sampling, Nation of Millions is one of the most sample-ridden recordings ever made, its layers coalescing and collapsing, its chaos barely contained. Scott Herren says of the record, “it sounded like science fiction.” It remains one of the boldest sonic statements not only in hip-hop but in all of modern music. The Bomb Squad experimented in the studio like Dr. Frankenstein in his laboratory. They built a body out of noise, and it came alive, thrashing everything in its past and in its path, including copyright law.Though Russell Simmons called them “Black punk rock,” Public Enemy stated: “We’re media hijackers.” About the song “Caught, Can I Get a Witness” from Nation of Millions, Chuck D says, “We got sued religiously after the fact, but not at that time. The song itself was just challenging the purpose of it”:

Found this mineral that I call a beat

Paid zero

I packed my load ‘cause it’s better than gold

People don’t ask the price, but it’s sold

Chuck’s use of the word “witness” is curious in our current context. “Cultural memory is most forcefully transmitted through the individual voice and body,” Hirsch and Smith write, “through the testimony of a witness.” In occult practices, a witness is an object that can link people across times, just as musical samples do. To establish such a connection is called a witness effect. Preston Nichols explains, “As a noun, it refers to an object that is connected or related to someone or something […] As a verb, ‘witness’ means to use an object to enter a person’s consciousness or otherwise have an effect on them.” A lock of hair, a piece of clothing, a proper beat, bassline, or vocal sample — any of these could have that bridging effect, tying two separate times together. The song ends: “They say that I stole this. I rebel with a raised fist; can we get a witness?” When their future is outlawed, the outlaws become the future.