“The periphery is the area that I inhabit in every aspect of my life. I used to resent this fact and fight against it, often with disastrous results. I’ve now come to embrace the notion that this is my rightful place. When all the free floating elements that constitute my life and work come to settle in place, this is where I find myself, and I’ve come to appreciate an intuitive ‘rightness’ to this outcome.”

– David Sylvian, August 2007

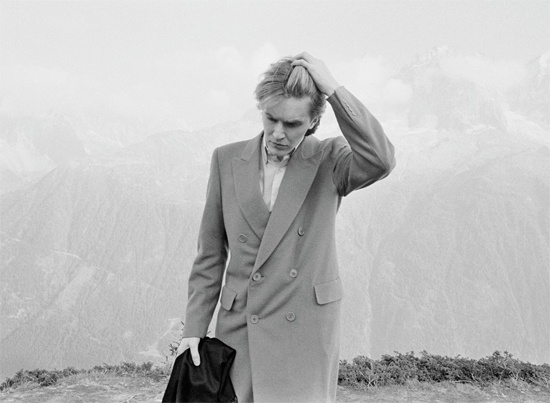

David Sylvian’s solo career has only further extended since the demise of the cult band Japan in the early 1980s – for which he was the frontman and composer – with July 2014 marking the 30th anniversary of the release of his first and highly acclaimed solo album, Brilliant Trees, since which this enigmatic artist has taken his audience on a journey from the heart of the pop machine to the fringes of musical experimentation.

From the time that Sylvian moved away from (the band) Japan, he has become more and more reclusive, and has – successfully, to a great extent – managed to disconnect himself from the glare of publicity and media interest or intrusion. As such, as his musical output has only become more and more worthy of analysis and scrutiny, information on the man himself and his motivations has become harder and harder to find.

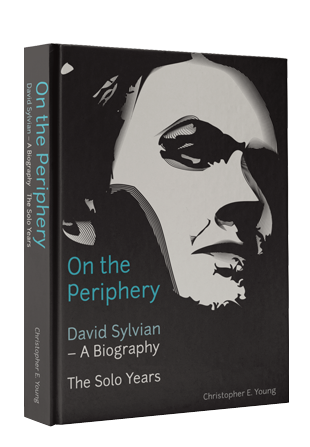

Attempting to put together the pieces, and fill – as much as possible – the gaps, however, is the recently released biography, entitled On the Periphery and of which I am the author, which tracks Sylvian’s career up to present day, beginning with a review of the legacy of his time with Japan, and fusing together an analysis of the man and his music up to the end of 2013.

A tough assignment. And one that took me over 4 years to complete.

I guess you could call this project a labour of love – you’d have to look very hard to find a subject more difficult to research than David Sylvian. However, the amount of time necessary to get to the heart of what makes this seminal musician tick, and to understand the motivations behind his work and the meanings contained within it, are extremely rewarding. And, as the story began to develop, the composition of the book – putting it all together – became somewhat addictive!

After painstaking research, first hand interviews, and analysis of a mountain of rare and obscure written material, On The Periphery provides a route map to assist in navigating complex terrain – the twists and turns in Sylvian’s musical, personal, and spiritual life.

The overarching conclusion reached is that singular strains alone yield little result: each aspect of Sylvian’s life feeds into and off of the other. As such there can be no credible attempt to analyse Sylvian’s career without acknowledging this intricate connection – one that can be seen in broad terms, and deciphered by close analysis of the meanings of the lyrics conveyed in his songs over the decades. This is one of the things that the book sets out to achieve, knitting together thousands of individual threads in order to build a coherent and compelling story of someone I consider to be one of the most influential modern composers of our day.

The book is available for purchase exclusively through the independent website www.sylvianbiography.com, and people interested in finding out more about On the Periphery will find more details and information on this site. There is also now a community of 13,000 facebook followers that are discussing the book, and where the author places frequent posts at www.facebook.com/DavidSylvianBiography.

Part 3. The Grey Skies

(Chapter 11 – ‘Truth Sets In’,

Pages 240-241)

Sylvian as a man found himself — after a sustained spell of positive creativity with the releases of Brilliant Trees, Gone to Earth, Secrets of the Beehive, and all the results of his fruitful collaborations in the 1980s — totally at his wits end, falling into depression, and completely unable to compose. There were points when he even contemplated throwing in the towel, and turning his back on the music industry completely. “I was completely numbed by that experience. I couldn’t write about it at all. It wasn’t even an option. The whole thing took me at least five years to work through, psychologically. I don’t think I could have got through it on my own, the feeling of guilt, unhappiness, and grief were too great. When someone dies you have the actual physical loss of that person. But when an important relationship ends, that person is still present in your life to some degree, and that confuses the issue enormously.”

This stood in stark contrast to the period from 2003 onwards. Testament to how much Sylvian had matured as a man — personally and spiritually — and how much he had matured as a musician, he not only managed to sustain himself better when dealing with the upset of his relationship with Chavez disintegrating, but he used music as a key to working through his issues. In other words, music was part of the solution, not part of the problem. “This time I felt better equipped to face the emotions head on. I am very involved in certain forms of meditation and ritual worship and so on, and I think having those practices gave me a relatively well balanced frame of mind which helped me to look deeper into the darker aspects of my own emotional make-up, and to emerge from it. This time, music was all I had to fall back on. It could be of service to me in the way that it wasn’t back in the ‘80s. I’d just finished work on the retrospective for Virgin. I was ready for a complete break from all that. And having built my own studio at home in New Hampshire, I was able to enter into the space that was entirely my own. I had the freedom to explore my own ideas, and without the usual time constraints.”

Blemish was recorded in just 6 weeks — for once a time restriction that was self-imposed despite the complete freedom Sylvian now had — as he wanted to discipline himself to focus on the work. The album represented a huge step forward in Sylvian’s musical evolution, despite the unfortunate inspiration that led to its formation. Sylvian had to a greater or lesser extent tinkered with the deconstruction of the traditional song format over the years of his solo career, but with Blemish, this deconstruction reached its zenith, and what was produced was a deeply disturbing and challenging musical composition that combined uncomfortable themes with sometimes discordant and innovative musical forms. Here was an artist using his music in a cathartic way, using the 6 weeks of composition time to become deeply introspective and work through the issues at hand.

Go back in time to the early 1980s, and Sylvian described the liberation he felt when embarking upon his solo career, as he found himself able to write about issues that were not fully evolved or complete. Now, music itself was being used to help him resolve the issues! “A lot of things that I couldn’t face in my life I could face in the studio environment. I would close the door and start working and open myself up to whatever came through. And often it was very negative emotions. And I thought, well, I’ll just look straight at them, and more than that, I’ll take them even further than I feel them in my daily life, because I wanted to go as far with them as I possibly could. I felt safe doing that, I felt that there was a strength inside of me to pull back at the end of the day and to be able to do away with those emotions. So I was pushing myself deeper and deeper into the negativity of the experience, wanting to know what that felt like. If you let yourself go to the point of hatred, how does that surface, and how do you give it voice? It was a way of experiencing those experiences and giving them all a new vocabulary that was pertinent for now.”

Sylvian decided that the American poet Robert Lowell had put his finger on it when he said that ugly emotions produce beautiful poetry. This was true of Blemish, which forced him to look into the darkest recesses of his heart and uncover what was there. In life this could be dangerous, but in the creative environment that he had made for himself in New Hampshire it was liberating to acknowledge these emotions, and have them as a stimulus for such innovative work.

The tone of the entire composition was dark and unrelenting, with perhaps an indication of some sort of peace and resolution only being felt at the very end. Sylvian did not resort to his usual modus operandi on Blemish, which was a solo work produced alone in his studio, with limited collaborations that were at arms length via electronic file transfers. The title of the album in itself indicated the complexity and depth of the emotional ride that the album would take the listener on as Sylvian explained to a radio station in Los Angeles when he was visiting the city to make connections that would get his record label moving. “I was dealing with emotions that it’s not easy to admit one’s experiencing or feeling until they become undeniably present. And there’s a lyric on the opening track Blemish which is alluding to the fact that there are some things in life you can’t turn away from, just like the discolouration of skin or whatever. It’s like ‘there it is, there’s my reality’ and you have to look at it and face it, it’s the emotional equivalent of that.”