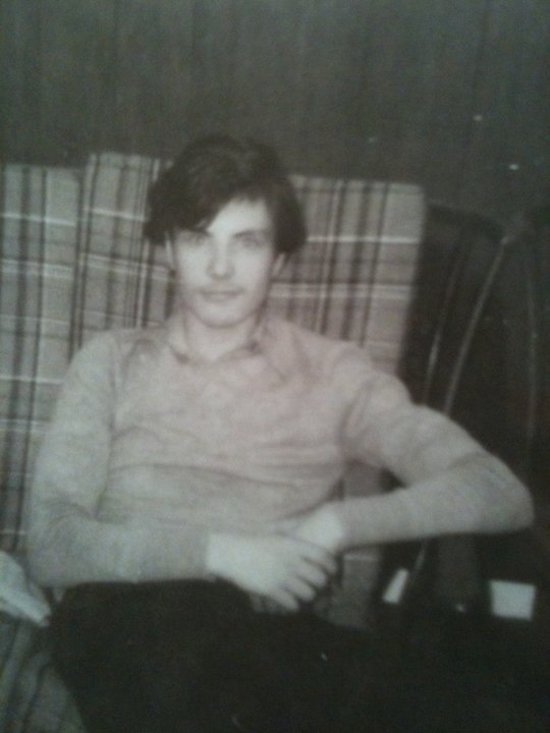

In the 21st century, the post-space age, in which time is marked not by developments in music but in advances in communications technology, in which practically everyone is carrying around with them a camera at all times, it feels extraordinary to relate that I only have about half a dozen photographs of myself from my teenage years. One in particular was taken around 1980, a grainy, black and white image. I am sitting in a room, in grey pullover and grey shirt, eyes gleaming with a sort of maniacal, sarcastic intensity, a wispy as wellas a genuine yearning, Midge Ure-type moustache sprouting tentatively above my top lip, staring out from beneath the beginnings of what would eventually become a Phil Oakey fringe, a synthpop hair curtain.

I was into the third year of a very intense relationship with music, which had begun when I acquired a cassette of Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions from Schofields, the department store, one of his great electronic soul masterpieces, limpid and funky, incandescently joyful and darkly immersive by turns. I read the NME, soaking it up as gospel, taking it entirely to heart, and yet disregarding its more mainstream, white-boy fare – Elvis Costello, The Jam. I was an international socialist by political inclination, albeit one who rarely left his bedroom. I wrote reams of awful, didactic, surrealist fiction. I was also very committed to my Catholic faith. I was teetotal. I had no interest in, or experience of girls, not even on a social level, let alone sexual. I spent absolutely all of my money on records – pocket money, dinner money, money from a paper round I was pursuing way past the ordinary retirement age, birthday and Christmas money. Badgered reluctantly into a holiday on the Isle Of Man with a friend, I spent the small allowance I’d been given on two albums in a record shop in Douglas – Terry Riley’s In C and and Irmin Schmidt and Bruno Spoerri’s Toy Planet.

I was drawn to unorthodox musics, the avant-garde, musics that made the most exciting and far-fetched advances into sonic space. This meant the likes of Captain Beefheart, The Mothers Of Invention, Magma, Can, early Pink Floyd, Robert Wyatt. It mostly meant electronic music, however. Some of this I had been able to absorb via the transistor radio – Kraftwerk, Donna Summer. Others, I absorbed from the NME and Melody Maker – Cabaret Voltaire, Pere Ubu, Throbbing Gristle, D.A.F, some from the mail order catalogue I received from Recommended Records, the label run by former Henry Cow drummer Chris Cutler, from whom I initially bought a copy of the dissident Czechoslovakian band Plastic People Of The Universe’s Egon Bondy’s Lonely Hearts Club Banned. From that I learned about, and duly purchased albums by, Sun Ra, Faust, AMM, This Heat, Video Aventures, ZNR and others. There were odder routes to discovery. Stockhausen I came across in a BBC2 documentary, of which I made an audio tape recording. Edgard Varèse I discovered via Frank Zappa, who included on his early album sleeves Varèse’s war cry “The present-day composer refuses to die!” Suicide I was prompted to explore following an item in Private Eye’s Pseud’s Corner featuring an extract of an interview with the duo in which they described the process of coming up with their name. For me, it was always a chase to the outer limits, the vital peripheries, where the truly interesting stuff was exploding in perpetual silence, rather than the white, male, guitar, orthodox centre (although in the case of ultras like Bob Dylan and Led Zeppelin I was more than prepared to make an exception). I never understood why there was such indifference and aversion to these glorious extremes of music, why music fans supposedly in the rebel throes of defiance embraced the tepid and familiar in such large numbers. It was a subject I tried to address much later in my book Fear Of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Don’t Get Stockhausen (Zero Books). It at once dismayed me but also confirmed in me a sense of the specialness, the apartness of myself as defined by music tastes.

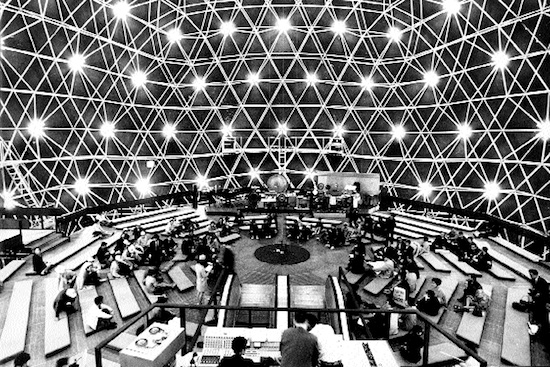

I was still in the grip of this music mania when I went up to Oxford University in 1981. I spent virtually all of the first instalment of my student grant on albums and EPs (including Thomas Leer’s “Four Movements”) , living the rest of the time on cheap biscuits, bananas, sherry and boiled eggs, mostly borrowed. I regarded student discos and house parties, with hearties rucking along to “Eton Rifles” and Duran Duran at full blast in the “bopping room”, which I regarded with seething, misanthropic disdain. I once hi-jacked a “bopping room” and played Sun Ra’s “Cosmic Explorer” at full blast for 30 minutes, as if to scour and clear the room with a flamethrower.

For me, electronic music represented am ostentatious fortress of solitude in my late teens; a means of imagining and embracing the entire world while wanting nothing to do with it; to escape and yet to be cocooned; to be noticed and to be left alone.

I was, in short, a painful little dick. However, I owe that lonely, frustrated, intensely inquisitive, yearning, hopeful, fearful, painful little dick everything. The basic foundations of my music taste were established before I was 20 (except for the women contributors – the women came later). And for all my mis-applications of the music, the extent to which I absorbed it became hugely educational and beneficial, the longer I reflected on it, far more so than the dubious second-class English degree I eventually obtained, based mainly on perfunctory speed-readings of the texts of Sir Philip Sidney and Edmund Spenser.

Portrait of The Author as a young man

Years later, I recouped the outlay on all of those records and became a music journalist, for a while very much at the centre of things but later a more distant commentator, as well as a better adjusted and socially skilful member of society. I was ultimately able to take in the full sweep of electronic music from its Futurist beginnings to its eventual, ironic, stadium rock-type domination in the era of EDM. I did so always from the point of view of the listener rather than the producer the cliché about rock journalists as frustrated musicians never applied to me. I was never interested in the tedious, nerdy, muso process of the nuts and bolts of construction of music but in its cultural outcomes, how it sat in the world once it had been thrown over the wall from the realm of production into the realm of consumption.

Still more years later, I pitched this overview of electronic music to Faber & Faber. I was not so much interested in a chronology or directory of its practitioners as a reflection on the hopes and fears generated by electronic music, from Utopia to Dystopia, its journey from a state of remoteness and otherness to sheer ubiquity, to debates about its authenticity. We’re in the future now and many of these debates have been settled in electronic music’s favour – Luddite resistance has all but vanished. But that outcome is too pat, too banally satisfactory; that Stockhausen’s function was merely to pave the way for EDM, pave it though he did. Yes, there are connections but there is the ongoing matter of forsaken futures, forgotten visions, vast, neglected space structures to be revisited.

The title Mars By 1980 came from an aborted project I set out to undertake in 1984, having graduated from University with no immediate future plans. I still had a valid ticket for the all-containing Bodleian library and sought to reconstruct/deconstruct the year 1975 through looking back in the media archives. I wasn’t prepared for the scale of such an endeavour and gave up but did call up from the library’s bowels bundles of old Sun newspapers from that year, in which they enthused about the certainty of an expedition to Mars by the year 1980 – the 80s, a decade whose character was utterly unwritten in the 70s, a blank page for speculation.

Revisiting the earliest pioneers of electronic music from Luigi Russolo, the Futurist composer and author of the Art Of Noises manifesto, through to Edgard Varèse, who had to wait until old age for the electronic devices he had dreamed of all his life to materialise, to Pierre Schaeffer and Stockhausen and the Darmstadt experimentalists, as well as Sun Ra in the realm of jazz, it was clear that their expectations for humanity in the 20th century were vast and that the machine age was just the first step in what would be a series of giant evolutionary strides for our species. (Stockhausen also predicted with great certainty that the world would have to go through some sort of terrible apocalypse “at the end of (the 20th) century or the beginning of the next”, reading which paralysed my impressionable teenage self with terror; would there even be a 1980?). Space, ultimately, would be the place, with the Apollo missions the first step in what would surely be a long and expansive journey beyond the bounds of orbit. Musique concrète, among many other things, felt like a means of mental preparation, of sonic visualisation of a time to come when humanity would exceed itself in barely imaginable ways.

Humanity, however, has remained resolutely earthbound. Rock’n’roll, the great postwar noise was a disappointment to the musical avant garde. Figures from Charlie Parker to Pierre Schaeffer held it in contempt. Indeed, rock would prove in many ways a reactionary force in many ways once it had established its hegemony. Much is made of the introduction of the Moog synthesizer in the 60s but it failed to bring down rock from its perch at a time when rock was all about the supreme posturing of the white mail virtuoso electric guitar hero. Although some fine Moog-scapey albums were made, it was too often a mere add-on, a special effect, a novelty buzz.

It was Kraftwerk who were most effective in using electronic music to reconfigure the popular song; their feyness and robo-antics were both deceptive and provocative. They reached back to the pre-war Bauhaus movement for inspiration, a melding of art and function. Practically everything they did was wilfully antithetical to the rock’n’roll spirit but Kraftwerk were not a novelty – they were the new.

It wasn’t just Kraftwerk, however, who eventually superseded rock and all its dominant assumptions. The duo Suicide, billed as “punk” years before punk, found a way of getting to an electric essence involving just vocals and electronics that made even The Sex Pistols seem over-elaborate and cumbersome. But punk itself, despite its three-chord guitar basis, opened up a new attitude of ideas over-aptitude which was ideal for a new generation of electronicists, from Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire to The Human League, Robert Rental and Gary Numan, all of whom benefited from the tumble in price of synthesizers in the late 70s to proliferate a new genre.

Fear and loathing of electronic music gradually gave way throughout the 80s and 90s, so much so that Kraftwerk effectively retired from the recording studio in 1986; their (ground)work was done. Rave’s revisitation of 60s communalism and vague idealism but led by relatively anonymous beatmakers rather than guitar gods set the seal on the ubiquity of electronica.

Here we are in the 21st century and there is a greater volume of new electronic music than ever before, much of it by women who have found a liberation in the genre denied them to the same degree in rock. It’s beyond gratifying; it’s more than the market can bear. And, here in the 21st century, in the post-space age, something feels missing; the strangeness and otherness of electronic music, its vast ambition and scope, of new dawns and colossal ideals. Perhaps that’s one reason for the modular synth revival – to hark back to the tones and tropes of electronic music’s emergent age. Mars and “1980” feel further away than ever, both physically and temporally and in the mind. But as I look again at the gleam in the eye of my 17 year old self, I wonder if, by reaching back far into the 20th century and listening again to some of its more neglected soundmakers we can reanimate some collective sense of hope, shock, awe, tap into realms of unexplored inner mental space and find our way to the future in the 21st.

Mars by 1980, by David Stubbs, is published by Faber