‘The European canon is here’ declared David Bowie on 1976’s Station to Station, signalling his allegiance to the new German music, crassly but enduringly dubbed Krautrock by the 1970s British music press. A marginal pop cultural force at the time, Krautrock is now firmly established in the wider rock canon, its sleek rhythms and cosmic explorations an inspiration to electronic shamen, underground freaks and indie-rockers alike. In Future Days: Krautrock and the Building of Modern Germany, David Stubbs deftly guides the reader along the Autobahn, offering detailed accounts of Krautrock’s key players, framing their actions within the context of a country rebuilding itself in the aftermath of the Second World War. The common impulse driving Can, Faust, Neu!, Kraftwerk and the rest, he argues, was ‘to begin again, utterly anew, start from scratch.’ This is manifested in their visionary music, which, diverse as it is, shares an interest in electronics, texture and repetition.

From the off, Stubbs makes it clear he’s not attempting an exhaustive trawl of every act that could be conceivably be called Krautrock. So if you’re a fan of Brainticket (too Swiss, too prog?) or Gila (too folky?), you’ll be disappointed. The premier division – Can, Faust, Kraftwerk, Neu!, Amon Düül and Popol Vuhl – are rightly given a chapter each, while other chapters cover the interrelated projects of the Berlin School (Conrad Schnitzler, Kluster, Tangerine Dream), the Cluster/Harmonia/Eno axis, and the acts associated with entrepreneur and cosmic chancer Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser (Ash Ra Tempel, the Cosmic Jokers). The chapter on ‘Fellow Travellers’ is a gleeful gathering of freaks – Guru Guru, Xhol Caravan, Anima – while a chapter on the Neue Welle of early ’80s Berlin – Einstürzende Neubauten, DAF – serves as an apocalyptic coda to the Krautrock era. Stubbs bookends all this with a thoughtful and wide-ranging prologue on the cultural and political context of Krautrock, and a final chapter exploring the influence of the genre on post-punk and electronic music.

For Stubbs, a defining characteristic of Krautrock is the transcendence, refusal even, of Anglo-American influences. Hard-rockers like The Scorpions are clearly not Krautrock, but neither are progressive rock bands like Eloi or Grobschnitt, whose debt to 19th century classical forms stands in contrast to the bracing modernism of Can, Kluster et al. One of Krautrock’s great paradoxes, adds Stubbs, is that ‘in order to invent anew, it was necessary… to reject Anglo-American dominance by drawing from it’. Several of the Krautrock musicians, Stubbs notes, cut their teeth playing rock and soul covers to American GIs stationed in the country. The influence of the Velvet Underground, Frank Zappa, Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd and James Brown on the Krautrock generation is indelible, but what Holger Czukay and his fellow ‘universal dilettantes’ did with those sources was extraordinary.

What distinguishes Krautrock from Anglo-American rock and pop, argues Stubbs, is its horizontality. It’s not about songs, ‘those small, vertical structures’, but what one might liken to a mapping of sound across space. Informed by the classical avant-garde and the electronic experiments of Karlheinz Stockhausen, texture is foregrounded. Vocals and lyrics are used for their sonic properties, rather than the expression of the self. Krautrock’s sometimes monomaniacal focus on what Mark E Smith calls the three Rs – repetition, repetition, repetition – does not resolve itself in the ‘ejaculatory relief’ of a guitar solo or anthemic chorus. Liberation is found in the ecstatic drive of a motoric rhythm or the astral trajectory of a kosmische drone.

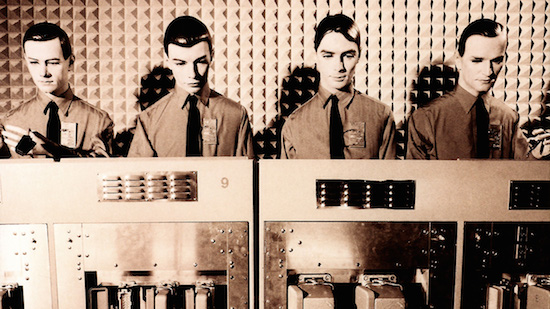

As Stubbs points out, there are no stars in Krautrock, no frontmen or frontwomen. At its most radical, as on Can’s pacific masterpiece Future Days, ‘all ego is sublimated… it is the organism that shines.’ The political implications of this approach are acknowledged throughout, without being overstated. Overt political reference was rare in Krautrock, but given the political awareness of many young Germans in the era of Vietnam, the Cold War and Baader-Meinhof, the country’s pop culture did not necessarily need a consciousness-raising Dylan figure. Writing for The Quietus in 2012, Taylor Parkes suggested that ‘Can’s collective action feels like a nagging dream… the communal, the collective, the sense of musicians as cogs in a machine’. From today’s perspective, the collectivism of groups like Can stands in contrast to the individualism of neo-liberal art. In the context of the time, it was not only a rejection of Anglo-American rock star egotism, but a necessary corrective to the legacy of Nazism, an embrace of communitarian values over the totalitarian fetish for Great Men. For all that groups like Kraftwerk, Neu! and Can aspired to play like machines, their humanism shone through.

For Stubbs, Krautrock reflects the process of renewal of German identity; not in a crudely nationalistic sense, but in terms of recognising the terrible crimes of the past in order to reconcile, heal and rebuild. ‘The convulsive vacillation in Krautrock between the axes of noise and beauty, metal and nature,’ he writes, ‘speaks about trauma and healing, destruction and rebirth, but at a subliminal, unspoken level.’ Stubbs argues that Krautrock’s experimental approach, where the ‘very materials and structure of the genre’ were radically altered, opened up space ‘for the flow motion of thought’. The genre’s interest in Space and the east, while representing ‘an escapism of sorts’, sprung from the need to create and incorporate ‘new areas, new dimensions’. Krautrock can be seen as articulating a politics of imagining, with Stubbs likening its practitioners to landscape artists, ‘depicting a real Germany and possible, physical futures’.

Perhaps inevitably, the chapters for which Stubbs has conducted new interviews have a vitality that those based on archival material cannot quite match. Can’s Irmin Schmidt and Jaki Liebezeit offer illuminating insights to their aims and working methods, while Faust’s Jean Hervé Péron is a seemingly endless source of hilarious anecdotes about the band’s on-stage nudity and Fluxus-inspired anti-performances. The reader is left amazed at how such an anarchic and brilliant group were able to persuade both German Polydor and Richard Branson’s Virgin to fund their antics. Yet even when Stubbs has to rely on older material, he chooses his quotes well, shaping often conflicting accounts into coherent narratives.

Throughout Future Days, Stubbs brings the music to life with sharp critical analysis and vividly impressionistic prose. Neu!’s ‘Seeland’ is described in terms of lapping water, with guitars that ‘wheel like lonely shooting stars’. Tracks as familiar as Kratfwerk’s ‘Trans Europe Express’ take on fresh resonance, as Stubbs evokes a train hurtling ‘cold and sleek, indifferent to its surroundings, bowling thorugh manmade carvings in Alpine rock’. Stubbs revels in gnarly noise too: Guru Guru are described as moving ‘up and down the registers like giant industrial hoists’, muffling ‘indistinct noises… in heaping mounds of gravel’. At one point, he adds, the listener is left ‘wading waist deep in rusty water’. What noise fiend could resist? As anyone familiar with his cantankerous alter-ego Mr Agreeable will attest, Stubbs can be very funny, and his self-mocking accounts of English attitudes to Germany and the avant-garde bristle with the wit of a post-punk PG Wodehouse. Recalling a teenage act of hubris in which he played Faust’s debut album to his grammar school comrades, Stubbs describes how his disgusted classmates introduced ‘a Dadaist element of chance of their own, by stomping their feet hard at key points, causing the needle to jump across the record. At which point, I gave up’.

Authoritative and highly readable, Future Days is the cultural and critical history the genre deserves, a joyful testament to the transformative power of art. Macht es neue!

Future Days: Krautrock and the Building of Modern Germany is out now, published by Faber & Faber