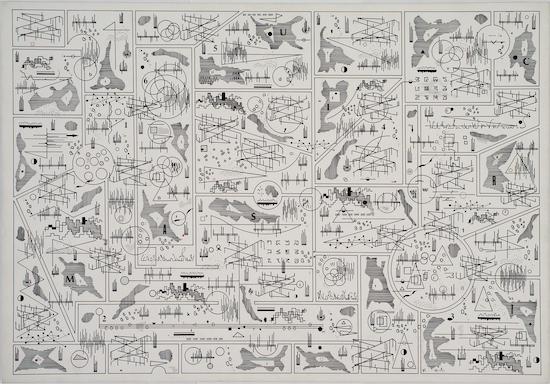

Bolesław Schaeffer’s graphic score for PR-I VIII, 1972. Collection of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łodź.

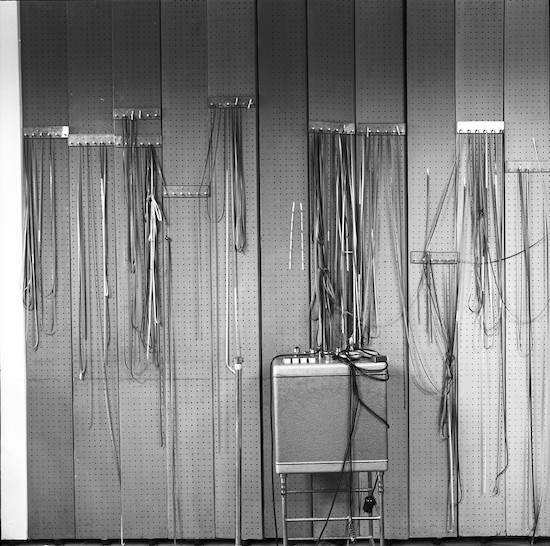

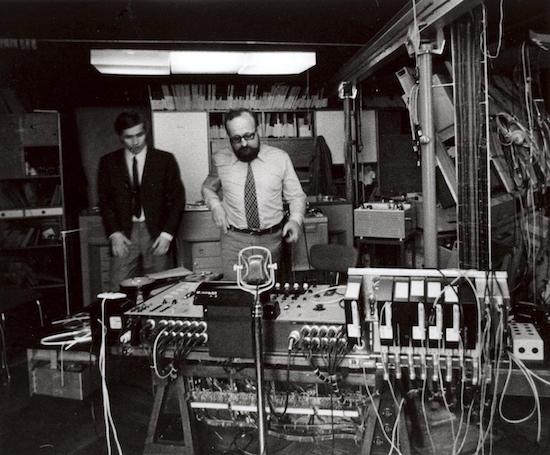

In 1963 a film crew arrived at the headquarters of Polish Radio in Warsaw to record a newsreel, a staple feature of cinema programmes at the time. The day-to-day activities of a radio station would hardly seem sufficiently newsworthy to warrant special attention. What had drawn the team to Malczewski Street were the facilities of Polish Radio Experimental Studio (PRES), a specialist recording unit that had been established by composer and musicologist Józef Patkowski six years earlier. They had built the studio to give composers access to recording facilities as well as to the electronic equipment and the expertise required to compose electronic and electroacoustic music. Entirely new timbral colours and sonic textures could be created and combined in situ by a composer without the need for musical instruments, musicians or the conventional tools of composition such as notation. In the absence of familiar signs of musical creativity, the crew trained their cameras on the ranks of dials and switches, and the spinning reels of the studio’s tape recorders. Two engineers – Eugeniusz Rudnik and Bohdan Mazurek – were recorded checking the instruments, making precise timings with a stopwatch and splicing ribbons of tape.

The newsreel was completed with a narrator explaining the work of the studio over a soundtrack of electronic music:

Sound and static generators, filters and modulators. This is the set of instruments operated by Józef Patkowski and his colleagues at Polish Radio Experimental Studio. This is where the boldest ideas of the creators of concrete music come true. Right now, we can hear one the recording … Stereophonic tape recorders and clips of tape used for sound illustration for radio, film and television. Some call it a cacophony of decibels. Others, a joyful song of the future. But that is what the right to experiment is about.

Perhaps anticipating the likely disdain of Polish cinema audiences for the strange and sometimes dolorous music, the narrator seems to answer the question: what is the point of this specialist recording studio? The report’s sign off – ‘the right to experiment’ – was a striking justification for PRES and its products, especially when the work of all creative artists in the People’s Republic of Poland, including composers, had been measured in terms of ideological commitment in the years before the studio had opened its doors.

In the late 1940s, Polish composers – like all creative artists who found themselves in the newly formed Eastern Bloc – had been put under considerable pressure to follow Soviet direction. All public forms of musical expression – commissions, concerts, broadcasts and recordings – were expected to serve the project of ‘building socialism’ by conforming to the official doctrine of Socialist Realism. In 1948 Zofia Lissa – a prominent musicologist – who was to play a part in the development of PRES signed Polish music up to the Soviet programme at the Second International Congress of Composers and Musicologists in Prague in 1948. Beata Bolesławska writes: ‘she thus condemned her Polish colleagues to aesthetic assessment according to the following four aims: avoidance of subjectivism; cultivation of national character in music; adoption of well-known forms; and increased involvement by composers and musicologists on music education’. What particular forms of musical expression would best satisfy Lissa and the new gatekeepers of culture was never precisely outlined. Nevertheless, it was clear that atonality, serialism or other modernist innovations were now viewed as offences against socialism, demonstrating ‘contempt’ for the working classes. Composers who broke with harmonic or melodic conventions or who simply eschewed easy comprehension were accused of formalism and elitism and often publicly admonished, sometimes in the most hysterical terms. Those who drew the strongest criticism had their membership of professional associations withdrawn, effectively ending all opportunities to have their work broadcast or performed in public. Others were bullied into conformity.

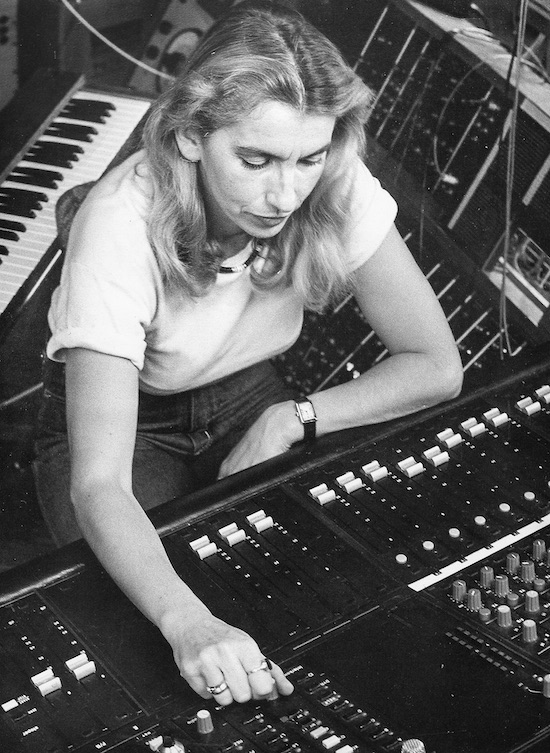

Elżbieta Sikora at PRES

Ten years later, the first composition created at PRES – Włodzimierz Kotoński’s Etiuda na jedno uderzenie w talerz (Study for One Cymbal Stroke, 1959) – rang the dramatic changes that had occurred in the People’s Republic. A single strike of a cymbal was recorded on magnetic tape and then transformed using the studio’s filters. Kotoński described his exacting treatment of this sound source:

In contrast with the vast majority of the earlier works of concrete music, the material was treated in a strict manner derived from the serial electronic compositions. The sound of the cymbal was filtered on five bands of differing widths and transposed on eleven pitches, in accordance with the adopted scale. A specific time scale of eleven durations and six articulation methods was created based on the ratio of the sound duration to the pause that followed within the sound’s time unit; a corresponding dynamic scale of eleven degrees and six forms of envelopes (three attacks and three releases). The entire work was composed in accordance with the principles of total serialisation.

There was little in Kotoński’s method – or in the piece itself – which could be described as ideological work.

Kotoński’s composition was the first in what was to be a remarkable line of musical productions. Patkowski imagined PRES as a kind of laboratory where a composer, working closely with a skilled engineer, could manipulate sounds materially (by editing and joining tape) and electronically (using oscillators, filters and a ring modulator). The studio provided the tools for numerous Polish composers including Kotoński, Krzysztof Penderecki, Bogusław Schaeffer, Elżbieta Sikora and Krzysztof Knittel to experiment with new sounds and ways of composing. It was also host to Hugh Davies, Arne Nordheim, Kåre Kolberg, Lejaren Hiller, Roland Kayn, and Dubravko Detoni and other guest composers from around the world. Meeting one of the practical functions that had been claimed for the new facility, numerous film scores were produced there (more than 100 in the first eight years according to a 1965 source). They included electronic music and musique concrete for experimental films, a genre for which the People’s Republic of Poland drew international praise, as well as feature films such as Penderecki’s extraordinary soundtrack for Rękopis znaleziony w Saragossie (The Saragossa Manuscript, 1965) directed by Wojciech Has. Such was the studio’s reputation that it supplied soundtracks for movies abroad too, including Alain Resnais’s excursion into science fiction, Je t’aime, Je t’aime (1968).

As the essays contained in this book testify, the creative achievements of the composers, musicians and engineers in this small outpost of electroacoustic invention were considerable. But what was the value of this highly specialist institution to its patron, Polish Radio, and, by extension, the Polish state? What ideological or social purpose might be served by Kotoński’s Study for One Cymbal Stroke? After all, the project of building socialism (or, from a different perspective, of maintaining power over a society which periodically expressed is objection to Soviet rule) would appear to have little interest in serialism, musique concrète, electronic music and other preoccupations of the avant-garde.

Courtesy of Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Photo: Andrzej Zborski.

The Sounds of October

The answers to these questions lie in the particular set of circumstances in which the People’s Republic of Poland found itself in after the death of Stalin. The dictator’s unexpected demise in March 1953 did not lead to an immediate dismantling of Stalinism, the brutal system of coercion and outright oppression which had been imposed on Eastern Europe in the late 1940s. The herald of change turned out to be the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in Moscow in February 1956 at which the violence and cruelty of his regime was admitted by First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev in his ‘Secret Speech’. Leaked soon after, it was a trigger for the wave of public disaffection which broke across the Eastern Bloc in the months that followed: in Poland protests spilled onto the streets in the city of Poznań in June. The Party struggled to maintain rule. In October, Władysław Gomułka was elected to the position of First Secretary of the Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza (Polish United Workers’ Party), with considerable popular support. He set about distancing the new regime from Moscow, promising greater democratisation and freedom of expression, and dismantling Stalinist policies (like the collectivisation of agriculture).

To exorcise the ghosts of Stalinist irrationalism and violence, the post-Stalinist authorities in Eastern Europe turned to science, technology and other ‘rational’ measures of modernity. In 1956 Soviet Premier Nikolai Bulganin announced the Scientific-Technological Revolution (Nauchno-tekhnicheskaia Revoliutsiia), a programme intended to shape a new Soviet consciousness. A scientifically literate and technologically expert society would be better able to compete with capitalism in the Cold War. A new future was anointed by the launch of Sputnik in October 1957 which was to be shaped by cybernetics, artificial intelligence and computing, television, electronics as well as other ‘clean’ technologies. Progress in these fields was inevitable, at least according to the technological determinism to which Marxist-Leninism subscribed. In a bullish mood, Gomułka took the stage at the Third Congress of the Polish United Workers’ Party in Warsaw in March 1959 to announce new conditions for intellectual life: ‘An atmosphere of free discussion in science, broadening contact with science all over the world, not excepting the capitalist countries, daring in handling new themes even though we are not always in accord with the directions this daring sometimes

takes. These are all developments that are conducive to intellectual revival and are propitious for scientific progress.’

Courtesy of Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Photo: Andrzej Zborski.

This turn to science was a key factor in the establishment of PRES in autumn 1957. Patkowski, who studied in the music and physics faculties of the University of Warsaw, was later to highlight the fact that the studio’s first team was not made up of composers, ‘just highly qualified sound engineers and device constructors’. In point of fact, the post-Stalinist state permitted experiments in culture and science to be carried out not only by cyberneticists, psychologists or ergonomists, but also by composers, visual artists, film makers, architects, and musicians too. And PRES was one of a number of specialist facilities established during the period of de-Stalinisation to support this new zone of experiment. Many galleries, theatres, film and recording studios were described – by their creators – in the 1960s as ‘laboratories’. Belonging to the newly-licensed zone of ‘experimentation’ and sharing the official rhetoric of progress, these culture labs enjoyed access to funding and sometimes imported technical equipment, as well as relative autonomy, as Dariusz Brzostek and Joanna Walewska-Choptiany outline in their essay in this book.

This was also the context in which PRES’s composers and studio engineers were conscripted into the task of reviving the science fiction film. (This genre had not been approved during the Stalin years according to one commentator because it had been a vehicle for expressing early doubts in the early years of the Soviet Union about the possibility of utopia.) Sci-fi was the popular front of the Scientific-Technological Revolution. Cinema images of space craft speeding through dark universes, intelligent robots, flashing computer consoles, aliens speaking unknown languages, and exploding stars were accompanied by electronic soundtracks made in the studio. One of the first sci-fi movies of the new era was Der Schweigende Stern (The Silent Star, 1960), an East German production made by the famous DEFA studios with an international cast and based on Stanisław Lem’s short story Astronauci (The Astronauts, 1951). On the screen, communism has swept the planet and mankind enjoys the benefits of nuclear technology and biological engineering. International rivalries are a thing of the past. A threat to this happy utopia comes in the form of a mysterious object that, when decoded by ‘the world’s largest computer’, seems to threaten the destruction of the Earth. A spaceship is dispatched to Venus, the source of this ‘cosmic document’. There, the international crew find the ruins of a civilization that had itself already perished in a nuclear civil war. Drenched in pathos, the film’s message was unmistakable. Polish composer Andrzej Markowski recorded the soundtrack for The SilentStar at PRES. The studio’s team, including Szlifirski and Rudnik, produced suitably extraterrestrial sounds by constructing an electronic oscillator which the composer could manipulate – like a theremin – with the wave of a hand. Using PRES’s magnetic tape recorders, Markowski, the composer, produced a brilliant sonic collage. Elements of the film’s sound design – like the musical interaction of astronauts with the illuminated keys and buttons of the on-board computer – overlap with the highly atmospheric soundtrack. As The Silent Star made clear, electronic sounds were destined to play a part in humanity’s future.

The foregoing has been an extract from David Crowley, ‘Introduction – “The Right to Experiment” in Ultra Sounds. The Sonic Art of Polish Radio Experimental Studio, published by Kehrer Heidelberg Berlin with Adam Mickiewicz Institute, ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź