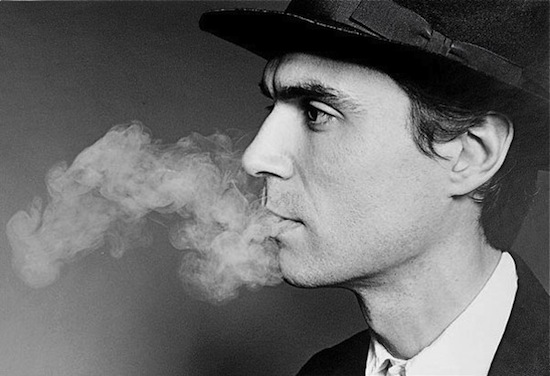

Whether it’s with his most lauded project, the genre-defining American New Wave band Talking Heads, working solo, or one of his many collaborations – most recently the album Love This Giant with St. Vincent – it’s safe to say that Scottish-born David Byrne’s impact on and contribution to the music industry since the 1970s has been, at the very least, significant. Perhaps more accurate, however, is that his presence and that of his impressive discography in contemporary music is seminal: a search of The Quietus archives alone returns 187 results – a slew of articles, reviews and interviews that either relate to Byrne directly or mention him by name in some (often reverential) way.

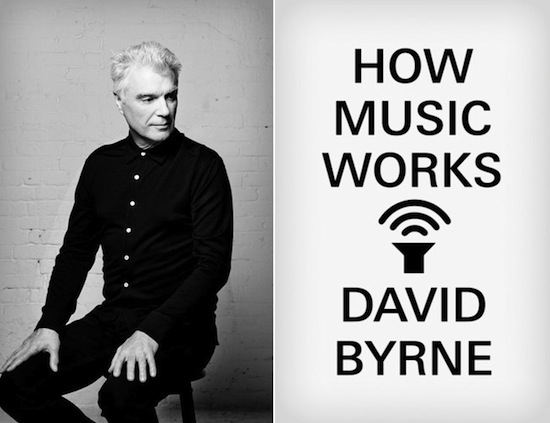

Now 60-years-old and no longer content with being a giant in only the music world, Byrne has now written nine books. His most recent, How Music Works, is an ambitious attempt at understanding a phenomenon to which the former Talking Head has dedicated his life’s work: the not particularly slender volume contains more than the usual musings on what makes good music – How Music Works is a study, by the man perhaps most well-equipped to carry it out, on what makes music at all – posing, rather than "What", the more nuanced questions of "Why?" and "How?"

It may disappoint some that How Music Works is neither biography, nor discographical history; there are references to Byrne’s own work and, yes, his time in Talking Heads but they are just that – points of reference. Between the covers of How Music Works, the author (described acting as "historian, anthropologist and social scientist" in these pages) creates a topography of music; an unselfish and far-reaching study on the evolution of sound in cultural and social context. While his knowledge of and contributions to the field are incontestable, for some readers David Byrne’s ninth book will seem a dry, almost academic effort. For others it will be a revelation…

Q & A With David Byrne

Did you have an epiphany about the importance of the context of music or was it a gradual realisation that the production of music depends less on the autonomous “genius” of the musician and more on the type of venue that they intend to play in or the type of format they intend to release it on?

David Byrne: It was a gradual realisation how extensive this was. I’d written a couple of pieces that appear in the book as magazine articles or blog posts and then I started to realise, “Oh, these all have to do with different contexts that music occurs in, whether it’s the way a room sounds affecting the kind of music that gets played in that room or the way that music gets paid for and distributed allowing people to make a living, which affects what music gets produced as well.” So I thought, “All these different things in unexpected areas really affect what we end up hearing and what we end up hearing is not just the expression of the creator but this expression which has been moulded by external forces.”

Given what you’ve just said, all of these observers who sit round passively waiting for a new movement to happen, a new punk or a new disco, do you think – to borrow a phrase – that they’ve got it arse about tit? Would they be better off looking for a new style of concert venue, a new format for releasing music on or a new drug or something like that first?

DB: Maybe. Maybe. Or maybe it’s more a case of looking for venues that already exist that are about to catch fire or finding out how people listen to music. Like people listening to music on their phones [laughs uproariously]. Because some of them do. I have some friends who listen to music on their phone speakers and that’s the kind of sound quality that they’ve gotten used to now. I’m not complaining about this, it’s just… Wow! Mind boggling…

I live on a housing estate in Hackney and listening to music via phones seems to be quite commonplace. Now, while I have the luxury of having a good stereo system at home, it did make me think that when I was a teenager myself the stereo equipment I used wouldn’t have been much better in audio quality – and that’s certainly when I got the most raw, emotional enjoyment out of music.

DB: Well, it’s not to say that the quality of the music should sound terrible but you’d have liked it even more if it sounded better. I guess it’s true for me as well though. The first music I listened to on my own was from a little transistor radio with a tiny speaker which probably didn’t even sound as good as the speaker on a phone.

Can you give me some examples of how the sonics of various venues that you’ve played have guided the music that you’ve produced, either as Talking Heads or a solo artist?

DB: Well, often with a pop band you’re a little bit at the mercy of the booking agent or promoter who is responsible for putting you in various venues and you get a very quick education in the idea of certain venues sounding great so that the audiences and bands love it. But just as often you’re booked into the local gymnasium and people may rush out to see you but as a musical experience it’s horrible. You realise really early on that your music does not sound good in gymnasiums.

It doesn’t follow that a fancier place makes the music sound better but most places sound better than a gymnasium. To me certain kinds of things work better in different settings. For example at an outdoor music festival, unless you’re a hugely popular act, the crowd really won’t want you to play a lot of new stuff. It’s not a place for quiet attentive listening. There are so many distractions; all the people around you and all the other visual distractions. So the sound can be ok but it is the visual element that makes you gravitate toward the material that the audience is going to be familiar with. Maybe you’ll save the new material for somewhere else that encourages the focus of attention.

How have the appearance of new formats such as 12”, CD and MP3 influenced the kind of music that you’ve written and released over the years, if at all?

DB: With me, not so much – only a little. It used to be with vinyl that you couldn’t put too much low end on a record. With CDs and digital formats you can put as much low end on a recording as you want; you can have huge sub bass on recordings, and essentially over the last decade that has become part of the sound. It’s also become a significant part of the music that’s out now. Technically it couldn’t have happened before. It’s not something that I use a lot but it is now part of music in general.

You touch on the idea that the dawn of the mass production of LPs caused a pole shift in perceptions about popular music – the record came to be seen as the primary source of music and the live concert merely a secondary reproduction. Do you think the probable collapse of record labels will cause that perception to flip back?

DB: To some extent; it means that some acts will have to survive monetarily by playing live. They’ll have to get good at it. Put on a decent show and make money at it. They can’t expect live shows to be funded by the record companies. That won’t happen anymore. On the other hand, not every act can do that. Some acts are just not a live act. Or they could be but the person who is writing the music is much better in the studio – or something like that. And other, younger, emerging acts, without being known, they can’t get a booking. I mean, they can get a local booking but 100 miles up the road they can’t get a booking because no one’s heard of them. So there’s not much chance of making a living playing loads of club dates. They need that extra push that a record label or a marketing firm or some other entity would have given them to get awareness of them up enough for them to play enough dates to generate a bit of income.

It’s a tricky thing. Acts like myself have enough of a name that we can go out and earn money but for acts just starting out, it’s something else they need to worry about, making enough of a name for themselves so they can go out there and start earning money.

In Europe and over in the States, what can we learn from El Sistema in Venezuela?

DB: [laughs] I think it’s actually being tried out at the moment in parts of the UK! If it were me I would open it up musically – have it not just be classical music – because I can see value in pop. Learn to make the music that you can hear. Whether it’s programming beats or playing a piano to play jazz, you can do that. It’s not beyond you.

I think that violence and truancy in schools would drop if there were regular punk and hardcore sessions!

DB: Yeah. All that. Punk and everything else. It’s all of equal value: it would be huge and not just getting kids involved in music but instilling in kids a feeling of self-worth, that it’s not a dead end life, that there is value in self-expression.

It has a knock on effect outside of music…

DB: Yes – a huge effect. You could be talking about a kid who otherwise only sees a future for themselves as a drug dealer. They may not have a future as a professional musician but this presents the idea, “Maybe I can do something else.”

Can you explain how the Third Reich and Bing Crosby’s love of golf were responsible for the post Second World War boom in record sales and some of the advancements in musique concrete?

DB: I got this from another guy’s book actually. Greg Milner wrote a book about the history of recording technology. During the Second World War there was an American called Jack Mullin who was stationed in Paris. He would hear symphonies playing late at night on German radio. In Europe and the States at the time the only way you could have a symphony broadcasted on the radio was to have the orchestra in the studio. He realised that Hitler probably didn’t have orchestras playing live at 2am every night and that he must have had some kind of recording technology that could make it sound as if it was a live broadcast. This was significant because the recording technology that the allies had at that time didn’t sound anything like a live broadcast – it wouldn’t fool anyone. When the war was over, he was sent to Frankfurt and on his way back home he stopped at the German radio station where the broadcasts had come from. They found tape machines that had been modified to include a flux tone into the recording – an inaudible tone that gets added to the recording but helps the bias of the taped music.

At that time all German technology was up for grabs. No one was going to respect their patents for new technology and everyone was just grabbing what they could, whether that was V2 rockets or tape machines. So, Mullin dismantled two of these suitcase sized recorders and, along with 50 reels of tape, sent them to his mother’s house in San Francisco. He got home, reassembled them, learned how they worked and made a few of these machines himself and demonstrated them to various people in LA. One of the people who saw a demonstration was Bing Crosby who had a daily radio show. Crosby was an avid golfer and he longed to have days off when he could spend more time on the links improving his handicap. He realised that if this technology was good enough to record him then he could do two shows at once. He could do two, back to back and broadcast a show to California while he was out playing golf, and no one would know he wasn’t in the studio – like Hitler with his late night symphonies. So over the objections of some of his business people and people at the radio station, he said he would invest in it. So they got the tape machines going and from there all hell broke loose. And from there it was just a short step to multi-tracking and tape editing.

It’s hilarious that a lot of people like Pierre Schaeffer and Halim El Dabh…

DB: …owe so much to Bing Crosby! Ha ha ha!

It’s really obvious when you’re reading How Music Works that you have a lot of insights into how music fulfils various social functions. Given the nature of the album and the various sound sources it borrows from, I was wondering how any of these insights fed into the production of My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts with Brian Eno? What were you trying to achieve?

DB: What we were trying to achieve kept on changing. Brian, Jon Hassell, myself and a few other people, we were going through a period of crate digging, going through a lot of ethnic recordings trying to find what was out there. (The best of what was out there came to us via the French Ocora label. They were presented as if they were important pieces of music instead of being weird artefacts.) So at one point we had the idea that we were making a fake ethnic record and it would have fake liner notes about the “culture” of the music and how it was made and all that kind of thing. I think Can did some records which they referred to as ethnological forgeries.

This is something Holger Czukay was exploring in more depth on his album Movies as well.

DB: Yeah, he did that sort of thing. Then we moved on from that – we abandoned that idea, and I’m glad that we did. We were out in LA recording and we started imagining we were making the soundtrack to a television special that would feature dancers; poppers, lockers, break dancers doing the electric boogaloo that we were really into at the time. We thought we would make a soundtrack for these dancers. So on top of what we were doing before, now we were making dance music as well. So I think by constantly changing what we thought we were doing, the record evolved that way.

I think using the found voices was really just a clever way of avoiding the issue of who would be singing on it. Both Brian and I realised that if either one of us sang a song or sang most of it, it would be presumed that the person singing wrote the song, because that’s what people do. We thought we’d avoid the whole issue by having someone else entirely “sing” on it.

How Music Works is available now on Canongate Books

COMPETITION

To celebrate its release we have copies of How Music Works, signed by David Byrne, to give away to two Quietus readers.

To be in with a chance of winning, just e-mail your answer to the following question to comps@thequietus.com, with BYRNE in the subject line, by 5pm Tuesday October 30. It’s open to UK residents only, and to read the Quietus Competition terms & conditions, click here.

Q: David Byrne collaborated with Fatboy Slim to produce a disco opera about which notable figure?

A. John F. Kennedy

B. Imelda Marcos

C. Kim Jong-il

D. George Harrison