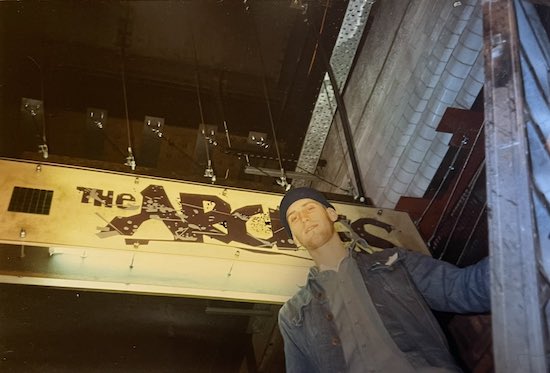

The original sign with its designer, Rory Olcayto

Tucked away in the catacombs beneath Glasgow Central Station, three new murals mark the spot where The Arches once stood. Renowned for its converted Victorian railway arches, experimental theatre, and the trains that rumbled overhead -– drowned out only by its club’s strident sound system – it was here that Scotland’s, and the world’s, most exciting artistic talent used to pass through.

Slam moved their formative techno night here from Sub Club in 1992, pulling in DJs like Laurent Garnier, Andrew Weatherall, and club patron Carl Cox. Daft Punk were in attendance as punters, so the story goes, before Slam’s label Soma Records discovered them and later invited them to play a historic set. An up-and-coming artist named Banksy exhibited in Arch 2, alongside Jamie Reid of Never Mind the Bollocks fame. Aspiring playwright Kieran Hurley debuted his rave chronicle Beats at The Arches’ Behaviour festival. And according to popular folklore, it was here that a Glaswegian crowd first chanted, “Here we, here we, here we fucking go!”

“My last ever day there after fifteen years, I had a wee walk around the place and it was really quiet,” says comedian David Bratchpiece, who together with novelist Kirstin Innes has penned a new memoir of the venue, Brickwork: A Biography of The Arches. “There was a theatre group rehearsing down in Arch 5 and they were playing ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow’. If you can imagine, that was bouncing off the walls down there. I shed a wee tear. I’ve never had such a connection with actual bricks and mortar, you know?”

Culture critic Joyce McMillan called it “cultural vandalism” when The Arches closed its doors in 2015. Like London’s Fabric, The Arches faced police pressure following a number of alleged drug incidents, including the death of seventeen-year-old Regane MacColl in 2014. Increasingly stringent regulations required staff to hand confiscated substances to the police, which the venue’s solicitors argued was used as evidence to back withdrawing its late night license. Unlike Fabric, the authorities failed to rescue The Arches, and the entire arts venue, which the club revenue had funded, went into administration.

In the years that followed, the absence of The Arches has felt like an open wound in Scotland’s cultural landscape. Nothing, according to Innes and Bratchpiece, has managed to replace it. Their book aims to recapture some of that cultural vibrancy that existed there for twenty-one years. “There’s still a scrabbling around to try and find it, I think,” says Innes. “The importance of it as a place where specifically young and working class people could access that sort of culture. It felt accessible to them. It didn’t have the gatekeeping that other places did.”

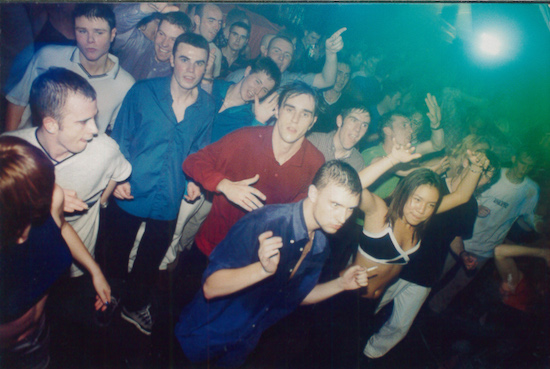

Massive Attack album launch party, 1997

“Hopefully it will give people a sense of closure. I know that it did for me personally,” says Bratchpiece. “I think it’s a closure that lots of people didn’t really get, whether they were coming from the arts/theatre side of things or the thousands of clubbers.”

Two days after The Arches shut for good, Innes published a blog post that shared her personal testimony of working with a team of mostly under-thirties on an internationally renowned programme of experimental theatre, visual art, and music. Most importantly, she touched on The Arches’ guiding principle, “this venue will always champion the right to fail”, which its founder Andy Arnold enthusiastically enforced. “And dear god, I saw a lot of shite,” she wrote. “That was the point of the place.”

“People need that space to work through things,” she explains. “The Arches functioned as this really useful crucible for emerging artists in that way, and it could only do that because we had the gigantic amount of money coming in from the clubs and bars.”

With the exception of the opening chapter, which sketches Glasgow’s industrial history that spawned those iconic railway arches, Innes and Bratchpiece have opted for an oral history told by the people who worked and partied in The Arches. The result is a holistic portrait of a music scene, which places the cogs that powered the machine – its punters and promoters – front and centre over its celebrities.

“It seemed like the perfect way to tell that story, because the real stars of the story are the people who made the place,” says Bratchpiece. “Dave Clark from Soma Records, and the promoter of Slam and Pressure, he said, ‘You’re going to need a Volume Two for this’. Like a Lord of the Rings-esque tome.”

“Lori Frater, that was a total chance one,” says Innes, speaking about interviewing The Arches’ first General Manager. “I hadn’t heard of her. Because of the way that stories get passed down, I thought it was always Andy who’d done it, and then Andy mentioned her. That turned out to be really key, her part of the story. I think the fact that it’s a twenty-four-year-old who came up with that groundbreaking model to have the clubbing revenue fund the arts – it had never been done anywhere in the UK before – that’s very, very Arches.”

Arches clubbers c.1990s

In the book, Frater’s account of those early Arches days recalls young people working round the clock for little more than the love of an idea. Frater herself never took a day off in two years. Often it was people’s good will that helped The Arches stay open, like the electricians who accepted payments whenever the venue could afford it, or the joiner who helped to lay a wooden dance floor with six hours notice because the council had refused a license in the morning, when The Arches needed to open for Slam that night. It’s that youthful persistence and DIY culture, according to Innes and Bratchpiece, that makes The Arches a definitive product of the 90s.

“For a start, we’ve got minimum wage now,” says Innes. “It is good that things are tighter, but at the same time I can’t imagine The Arches existing, if it started today at all, in that world.”

“That early 90s period was the real rise of dance music and raves moving indoors,” Bratchpiece adds. “The Arches was very much a part of that. That whole scene is completely different now. I don’t think those early days could ever be properly recreated.”

Reading Brickwork is a lot like reading a history of club culture. We witness the early euphoria of the rave scene, starting in 1990 when The Arches first opened, and the rise of the super club. We see increased pressure from policing and, tragically, subsequent closures. A growing tension between the theatre and club programmes reflects a question central to dance culture today – how far does a growing emphasis on profit and growth take clubs from their early 90s roots? Interviewees describe an increasingly busy schedule that provoked regular sparring between the club and the theatre, and in some cases staff burnout. There is a sense that even though legal troubles got The Arches in the end, it may have eventually become a victim of its own success.

“It was like beautiful chaos, but there’s no way it could have lasted forever,” says Bratchpiece.

“Niall Walker [who designed The Arches’ branding and the cover for the book] said that actually these places don’t last forever,” agrees Innes. “The Haçienda, for example. Places have their moments and then something happens and they change and move on. That feels emotional for us, but within the wave of how things work, twenty-one years is quite a good run for a venue of this sort. Not that there are many venues of this sort.”

Six years on from The Arches’ closure, the time feels right to revisit those twenty-one years. Innes and Bratchpiece describe an urgency to set down its history now, when enough time has passed that the grief has eased, before it fades from memory altogether – “and when you’re talking about The Arches, there’s a lot of faded memories,” jokes Bratchpiece.

“I’ll tell you how we finished. We did final edits on Slack, right?” says Innes. “It’s 3AM. I was like, ‘Are we ready to hand it in? Is this it? Have we finished it?’ Bratchie said ‘Yeah, I think we are.’ I was like, ‘Here we…’ And he was like, ‘Here we…’ And I went, ‘Here we…’ And he was like, ‘Ah we fucked it! Too many ‘here we’s!’”

“The one chance we had,” adds Bratchpiece.

“To make something beautiful and we fucked it,” says Innes.

There it is again – the right to fail. They may have messed up their big ending, but Innes and Bratchpiece have gifted us some vibrant memories of Scotland’s culture darling. What could be more Arches than that?

Brickwork: A Biography of The Arches by David Bratchpiece and Kirstin Innes is published by Salamander Street