Like her better known 2011 film Dreams of a Life’ Carol Morley’s 2000 documentary The Alcohol Years is a film about self and about memory. In The Alcohol Years, Morley’s hedonistic experiences in Manchester from 1982 to 1987 are refracted through a cracked mirror of reflections from largely terrible men – offering their memories of sexual encounters and drunken early mornings straight to camera, and often saying more about themselves than they were realising. If you want to get a flavour of pre acid-house nightlife in Manchester, watch The Alcohol Years. If you want to get a flavour of the smirking contempt some men can have for women, watch The Alcohol Years.

There is one exception in the film – Dave Haslam. Nobody deserves a pat on the back for managing to not make a creep of themselves, but watching The Alcohol Years a few months ago, I was struck by the Haslam that appears on screen – concerned, self-effacing and more interested in Morley as a person than anyone else in the documentary.

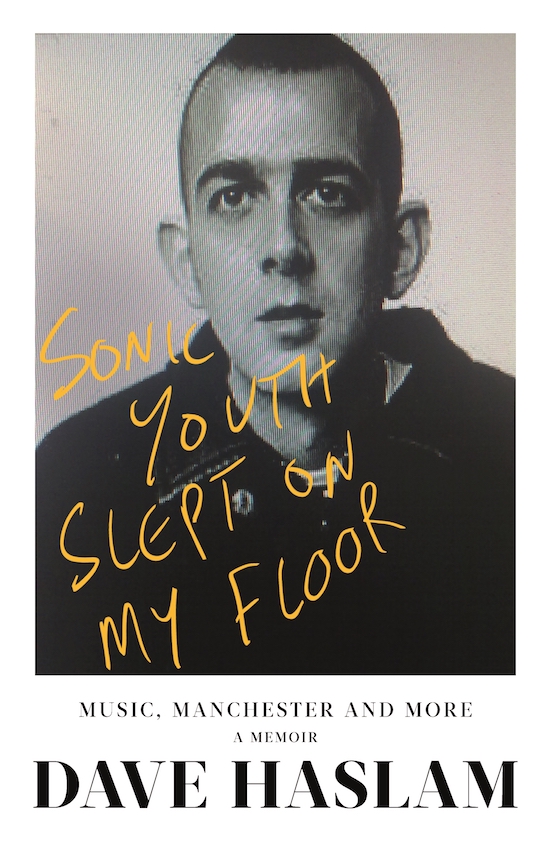

Haslam is an adopted Mancunian – born and raised to Methodist parents in Birmingham and attending the prestigious independent King Edward’s School in the city. There’s curiously little in his new book, Sonic Youth Slept On My Floor, about Haslam’s education – what provided Haslam with the wide-ranging cultural reference points that he would bring to his Debris fanzine at an early age? By way of explanation, Haslam does reference the expansive, street theorising of NME writers Paul Morley and Ian Penman.

In 2005, Haslam published Not Abba a counter-history of 1970s Britain, and he evokes this again in his descriptions here of a Britain mired in the shadow of the then unresolved Ripper murders. “Sometimes”, Haslam writes, “there are big, shared social calamities such as 9/11 that hang heavy in the air, and trigger clouds of anxiety and upset. The Ripper crimes played out over a number of years, darkening everything and changing the landscape forever.” With the exception of the nascent Dexys Midnight Runners, there was little in post-punk Birmingham to keep Haslam at home, and Joy Division’s performance in a local mod club becomes the catalyst for his decision to study in Manchester.

In 1983, Haslam published the first issue of Debris. He would interview local hairdressers, review South Manchester cheese on toast, and these features would sit happily alongside a thinkpiece on A Certain Ratio and his ruminations on Anna Karina. This juxtaposition of seemingly high and low culture, of the international and the fiercely provincial, clearly makes Haslam tick – as he was self-publishing Debris, he would take his haircut from the sleeve of 1984 hip-hop compilation Crew Cuts whilst taking his sartorial cues from doomed Soviet poet Mayakovsky (admittedly, a pretty natty dresser).

Haslam is gifted at evoking early 80s, inner-city Manchester. There’s Moss Side, where all-night clubs like the Reno operate under the radar in an area not yet associated with the gang violence that continues to unfairly stigmatise the area – gang violence helped in no small way by the dance boom of which Haslam was a key participant. And there’s his romantic evocation of a Hulme after the families moved out but before the developers and student hubs moved in – a riot of second-generation immigrants, listless youths, and vast, imposing crescents.

Mark Kermode lived nearby at the time, and both Haslam and Kermode were fans of the independent Aaben cinema in Hulme, where Haslam first watches Eraserhead (because capitalism in Manchester likes to come holding hands with nostalgia, the cinema site is presently being renovated into townhouses by the developer One Manchester, called inevitably, The Aaben.)

Morrissey was born in the old Hulme – documented by the photography of Shirley Baker – and probably still lives in a mythologised version of that old Hulme. He tells Haslam that adolescence “is special, it forms your opinions for the rest of your life. I think we shouldn’t really underestimate it.” Hmm…

Haslam misses the first Smiths concert for William Burroughs performing with Psychic TV (fair enough really). He doesn’t make the same mistake twice, and pegs Debris to the Smiths’ rise – gaining the first major interview with Morrissey in the fanzine. When the group finished, he got the exclusive Johnny Marr post-mortem.

Through her first group Marine Girls (loved by Kurt Cobain), Haslam meets Tracey Thorn and the two come close to beginning a relationship – alas, it is not to be as Thorn soon embarks on a relationship with Ben Watt that exists to this day. This does, however, prompt some of the best and most introspective writing in the memoir. “Whatever our relationship was,” Haslam writes, “it didn’t last long, but it meant a lot to me then, and still”.

He was, by his own admission, a young man suffering mild depression and lacking libido for years – returning to his 1980s, writing for the book, he sees this sadness seeping through into his features and his interviews. The short story writer Raymond Carver (“earnest, doleful… like a big bear resigned to being caught by poachers”) advises him that “sometimes those who need love most are least capable of inspiring it”. Frustratingly, Haslam does not return to this theme for too long, and the introspection is lost until the book’s close. So much so that when in the book he introduces the birth of his first child, the lack of context preceding this forces a double-take.

After years of obsessing over the minutiae of an indie band’s literary or cinematic influences in Debris, the retreat to the anonymity of house music was intoxicating for Haslam. Through the knack of being in the right place at the right time often enough, Haslam in 1986 began running the Temperance club night at the Haçienda on Thursday nights. Initially an indie night, Haslam soon began bringing into his set what would become acid house. For Haslam, the squelchy, brutally simple sounds coming out of Chicago and Detroit weren’t necessarily pointing towards a new future or some revolution, they just sounded very good indeed on a Thursday night and worked well next to New Order, Kraftwerk, or Giorgio Moroder.

What went up, however, famously came crashing down – with implications for the city that still oscillate to this day. If acid house had the power to galvanise and change lives, it also contained the self-same power to destroy lives. There’s no single, souring Altamont moment in Sonic Youth Slept On My Floor, but a low, anxious hum that builds to a crescendo of gun crime, turf wars, and senseless murder. Haslam has a gun pulled on him in the DJ booth one night.

Though ostensibly at the height of his career, it’s Haslam’s time DJing in the early nineties that makes for the least compelling section of the book. He’s running a weekly club night. He occasionally moves venue. He returns to the Hacienda. The Hacienda shuts down. The party is over. And for Haslam this means an uncertain future and the necessity of trading on his past.

In reality, this meant a baggy Faustian pact with the lumpen Madchester station XFM. Haslam grimaces through a regular slot where he has virtually no control over the playlist. The late Tony Wilson – another charismatic street theorist who Haslam greatly admires – sours against Haslam with an unpleasant and largely unexplained grudge that sustains until Wilson’s death. Haslam goes from being the man Wilson referred to glowingly as “my lead critic”, to sitting on Icelandic rock TV promoting 24 Hour Party People and being played a chilling audio clip of Wilson saying (without context and apparently in some earnest) “I’m going to have Dave Haslam shot. I’d like to shoot him.” This, understandably, spooks Haslam.

It’s at this point that the book turns inward once more, and Haslam writing is once again highly compelling. He writes of “falling into hollow hours following the intense highs of great DJ gigs and other big events… the build up to the big events, the all-consuming moments during them, followed by the draining comedown, the need to adjust from the adrenaline boost onstage to your offstage world.” His words will resonate with many a performer and clubber, and he writes about middle-age and depression with originality and insight.

There’s a pleasing cohesion to Haslam finding some level of solace in returning to the spirit of Debris. Like moving from Birmingham to Manchester all those years ago, it’s briefly relocating to Paris that shakes him into creativity and out of fussy habits. He begins promoting Close Up events – Q&As with artists like Jarvis Cocker, David Byrne, and Jonathan Franzen in which Haslam books the guest, the venue, and sorts the nuts and bolts of promotion. Though at times, Haslam recounting his onstage interviews can read like a shopping list of celebrity encounters, there’s cliché-free reflections on the conversations that work and those that fail to spark.

But what now for Manchester? Haslam’s role in the bi-annual Manchester International festival is covered here, but for a book subtitled “Music, Manchester and More”, there’s little reflection on the present and future of the city. The tendency towards civic pride – even from those rightly embarrassed by the city’s occasional cringing nostalgia – can mask anxieties about the lack of affordable living in and around the city. Promoters complain that the city is running out of cheap spaces to put on interesting or marginal events – though of course, the arrival of spaces like the White Hotel and the forthcoming Now Wave Venue are more than welcome. Haslam writes regularly and eloquently on these subjects, and some reflection in this memoir feels overdue. All the same, Sonic Youth Slept On My Floor is a resonant and thoughtful memoir. Manchester – and British nightlife in general – is lucky to have Haslam as its archivist.

Sonic Youth Slept On My Floor by Dave Haslam is published by Little Brown