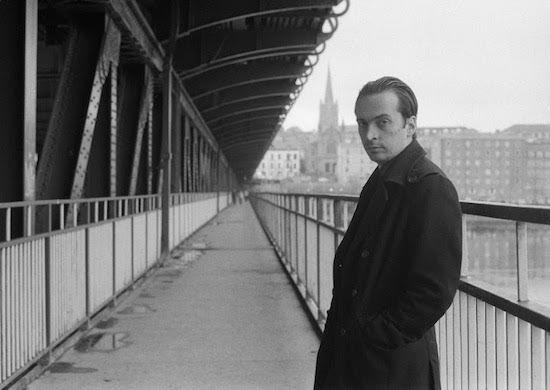

Darran Anderson by William Kelly

“Memory is not an instrument for surveying the past but its theatre.” – Walter Benjamin, Berlin Childhood around 1900.

After writing Imaginary Cities, which was relatively forward-facing, I wanted to look backwards and write a book about the past but it soon became apparent that there is no real ‘backwards’. There is only the present and what survives of the past in the present. So you end up really writing about memory, data and relics. And you start to find that Benjamin was right; that memory is a kind of theatre. On one hand, you’ve a moral responsibility to be true to what happened and on the other, everyone’s experience of the world is subjective and prone to amnesia, fictionalisation and contention, especially in a region like the north of Ireland. After writing about innumerable places in Imaginary Cities, I thought I was writing about a single city, my hometown of Derry, when actually I ended up delving into thousands of Derrys, all of them familiar but shapeshifting, through the prisms of other people.

Initially, I wrote this strange dark river book called Tidewrack about the Foyle, which runs through my hometown and has had a profound impact on my family, but that ended up in development hell for years for various reasons (melancholic Sebaldian nature books weren’t setting the book world on fire). It was not a good time and I was not in great health. Things, outside of writing, were sadly falling apart. The book became imbued with that, almost as if it were cursed. In a ridiculously theatrical moment, I threw the final draft of Tidewrack off the end of a pier in Scotland (one of the few surviving remnants is a playlist I played obsessively while writing the text in an attic overlooking the sea). I was adrift for some time after that.

And then I found an essay called ‘The Infra-Ordinary’ that changed everything. It was by the French writer Georges Perec, in a collection called Species of Space. I’m not sure how I came across it. It might have been the similarity of the title to one of my favourite books Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, which has been a huge influence on my work writing and talking about architecture and urban space. I’m not sure. Maybe some things are meant to find you at certain times. Perec had a similar approach to Bachelard. He questioned our surroundings and the things we take for granted and rebuilt the world from the bottom up, the way a child would – rooms, staircases, streets etc.

The following passage inspired Inventory, and gave it its name,

“What we need to question is bricks, concrete, glass, our table manners, our utensils, our tools, the way we spend our time, our rhythms. To question that which seems to have ceased forever to astonish us. We live, true, we breathe, true; we walk, we open doors, we go down staircases, we sit at a table in order to eat, we lie down on a bed in order to sleep. How? Why? Where? When? Why?

Describe your street. Describe another street. Compare.

Make an inventory of you pockets, of your bag. Ask yourself about the provenance, the use, what will become of each of the objects you take out.”

Perec sought to reactivate a forgotten sense of wonder, and a sort of radical curiosity therein, “To question what seems so much a matter of course that we’ve forgotten its origins. To rediscover something of the astonishment that Jules Verne or his readers may have felt faced with an apparatus capable of reproducing and transporting sounds. For the astonishment existed, along with thousands of others, and it’s they which have moulded us.”

Part of the problem of writing about growing up in the midst of conflict and division and dealing with issues like poverty and trauma is not only the risk of it being a misery memoir but that people retreat when such subjects are directly mentioned. We become skittish and defensive, especially true in a place like Northern Ireland where saying the wrong thing could’ve gotten you arrested or shot. We developed there an entire language of gestures and evasions, gallows humour and bullshitting as an artform, and ways of reading subtleties and silences.

Objects offered a way in. They are a conduit. You can speak about an object when really you’re talking about something else entirely, something that would dart into the shadows if you shone light directly at it. And the restriction of every chapter being an object was curiously inspiring. We don’t often think of limitation as being potentially liberating but it can be in terms of focus, which is why you used to get artists writing manifestos.

Music was one way we communicated in the years of silence. It could express inexpressible things; my mother listening to ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes?’ or ‘So Long Marianne’ exhausted after working until the early hours, my father singing songs to himself heading to salt the roads on dark winter mornings, mixtapes you exchanged as a means of flirtation, friends, who otherwise bust each other’s balls continually, embracing on dancefloors. The songs were as invested as objects are, and I was drawn to albums then that felt like cabinets of curiosities – Another Green World, Selected Ambient Works Volume II, Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, The White Album (whose working title A Doll’s House summed up its feel, at its best, of hidden treasures in darkened attics).

The following songs reflect certain aspects of Inventory and the time span it covers, up until the late nineties. They’re naïve and not much of a coherent mixtape but they are part of that memory theatre Walter Benjamin spoke of. Like objects, they can tell us very different things, depending on the listener. They’re all items, discarded and precious, “in the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.”

Dexys Midnight Runners – Dance Stance/Burn It Down

Irish diaspora soul music. A Trojan Horse protest song smuggled onto Top of the Pops. Searching for the Young Soul Rebels came out the year I was born, a grim year in the north of Ireland and not much better for those who escaped becoming ‘involved’ to go work on building sites in London. It was a route relatives of mine took and they instantly ran into hostility. Some changed their accents and tried to pass at Spurs and Arsenal matches or else they stuck to their own in working class Irish enclaves in the city. I still drink in those places and it was a hard, alienated existence for them. A different London.

In a way that combined anger and exhilaration, Kevin Rowland spoke out when it counted, when it was neither profitable nor fashionable. If the Irish are so dumb (an apparently acceptable prevailing view at the time), how come they keep rescuing literature here from itself? Perhaps things have really changed since then. Or perhaps the rage, fear and ignorance is just redirected elsewhere and onto other others, and the source of it all is unexamined. The ice under our feet may not be as thick as we like to imagine, especially when there are so many cynics now who profit from divide and conquer, and so much civilised silence seems to be preference falsification. Of course, it’s just a song. And a joke is just a joke. Until you start asking yourself what just really means.

The album version of this song starts with a radio as Inventory does. And the song is about questioning that which is usually accepted, as Perec recommended. The cover of Searching for the Young Soul Rebels features an image taken during sectarian disturbances in Belfast in the 1970s. I always assumed it showed Catholic families being burnt out of their houses, which happened to thousands of families, but there was a Twitter discussion a while ago that tells a far more complex but equally disturbing story. It has a sense of troubling ambiguity, memory being not just objective recollections of the past but the stories we tell ourselves and each other about the past. In Joyce’s Ulysses, the main character, Stephen Dedalus, claims “History is a nightmare from which I’m trying to awake.” The problem though is that often we don’t really know, or want to know, our history. We tell ourselves expedient stories because facing the complexities, contradictions and traumas of the truth are too daunting. In doing so, we remain in a sleep where new nightmares can easily form.

Rory Gallagher – Going to My Hometown

This song resonates for similar reasons. There was a time, post-Miami Showband massacre, when a lot of musicians would shun the north for fear of being targeted or they’d show up for some riot porn photo-shoots but Gallagher kept coming. These days we’re used to lots of noble causes being co-opted for marketing reasons by corporations, who were conspicuous by their absence when people were really in the shit. Gallagher kept coming through it all and when it counted.

There are some great shots of Belfast in this clip. It’s almost exactly how I remember Derry in my youth; parts of it looked like it was struggling to recover from some huge cataclysm, which in a sense it was, and I get the fear when I’m back home that it’s being allowed to sink. To be honest, I see this all over Britain and Ireland. Outside the bourgeois echo chambers, vast swathes of the country, and the people therein, are being left to fall apart. It’s an outrage that this isn’t seen or heard. At the same time, the ability to escape politics is an underrated political act, as this footage shows, even if it only lasts as long as the music does.

Talking Heads – Once in a Lifetime

My sister and I had this recorded on a glitchy VHS tape with bits of old adverts and songs from Grease 2 or whatever. At the time, tapes like that were just throwaway audio-visual detritus but I’d love to see it now that time has passed. Objects get invested with a kind of spirit. Brian Eno, who is all over this tune, wrote in A Year with Swollen Appendices, “Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit – all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided.” I kept thinking of that when I was writing Inventory – all those cassettes, floppy disks and broken phones, all the redundant technologies, that now seem to have an aura and contain lost stories now that they are obsolete.

My family were hippies. Not just my folks but most of their brothers and sisters. And when you grow up in an environment where everyone’s listening to psychedelic music and their heroes are South American revolutionaries, you have to really think long and hard about how you’re going to successfully rebel against them. The person I latched onto was David Byrne. I didn’t know his name so I called him ‘the Man on the TV’. I had this intense yearning to have short hair, wear a big suit, have a large automobile. And a beautiful house. And a beautiful wife…

Mississippi John Hurt – Lonesome Valley

The items we surround ourselves say something about us, even if it is a question of how we want to be seen or what we conceal. I remember going to relatives’ homes and they’d be filled with Catholic iconography and a lot of people on the other side of the divide has royalist iconography all over the walls. The house I grew up in was different. My da was obsessed with blues music so there were always guitars lying around and harmonicas. We had a framed portrait of Robert Johnson on the wall. I’m not sure what intrigued him so much about blues music (other than who needs Elvis Presley when you have Big Mama Thornton?) but whatever the attraction, the icons we grew up with didn’t come from on high, whether cathedrals and palaces. They were of people like Bessie Smith and Big Bill Broonzy. My earliest memory of drawing anything was trying to copy the covers of The London Muddy Waters Sessions and The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions.

For a long time though, I’d heard so much blues music, especially electric Chicago blues, that I could no longer quite hear it; the way if you’re painting a portrait foor too long, you can no longer quite see it. Then one day my da played a Rory Gallagher song that had the line “I’m gonna let the graveyard be your resting place” and immediately I asked “Who’s that?” and he told me it was an old Blind Boy Fuller song. In hindsight, it was a pretty mean, violent song and I was at the Mortal Kombat age when that had a morbid attraction. So I followed it into this other kind of blues I hadn’t realised existed, Piedmont, which was acoustic and haunting and full of tales of desire, murder, retribution, and which mixed spirituals, storytelling, blues, folk music, ragtime and country.

People like Skip James and Reverend Gary Davies who still give me the chills. They’re almost apocalyptic. Then you go through your own end times and you’re more inclined to find beacons of light rather than harbingers of doom and Piedmont blues had those musicians as well, above all in Mississippi John Hurt who seemed such a humble gentleman for all his talents. He had this lightness of touch that belied the fact that he was an incredible guitar player and he sung songs about his fondness for Maxwell House coffee or blues songs about how satisfied he was but he had these other folkloric tales too about John Henry and Casey Jones. ‘Lonesome Valley’ is so simple and so perfect. It feels ancient and no one really knows who wrote it or when. Maybe it’s always been around and always will because the message in it is so existential and poignant and comforting at the same time that we’re all already part of it before we’ve even heard the song.

Pink Floyd – Astronomy Domine

I used to sift through my da’s boxes of records religiously as a boy. There weren’t forbidden as such but it did feel irresistibly clandestine to discover music ‘yourself’ back when access to music was so scarce and had so much ownership and weight attached. Though it was mostly blues, folk and rock, he had some idiosyncrasies that were really formative in terms of teaching me that when you dismissed things too readily, you were only constraining yourself; for instance, he had an uncharacteristic liking for The Cure and Devo and I remember finding ‘Sign O’ the Times’ in his collection and the minimalism of it sounded so counter-intuitive that it was radical. Initially, I was hunting for the cover art of the LPs; all those surrealist/prog rock other-worlds that look incredibly kitsch now but did something to your brain as a child. I spent months studying the sleeve of Wish You Were Here, like it was an alien artefact. Over time, I grew to really love Pink Floyd, mainly for the sense of space in their records. I know a few of them were architecture students and there’s a sense of sculpting environments at work there, whether it’s claustrophobic (The Wall), expansive Wish You Were Here, submarine (‘Echoes’) or pastoral (all the songs that start with birdsong).

There’s no album more entwined with my childhood memories though than The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, especially the first side. A lot of which is due to Syd Barrett’s lyrics which have this haunting Victorian ghost-child nursery rhyme whimsy to them but it’s more than that. There’s an arc to that album. It has this initial exhilarating blast-off into the outer space with ‘Astronomy Domine’ and then collapses in on itself with ‘Bike’, which is such a glorious and disturbing singalong song. That combination of innocence and fear really chimed with me at the time and ever since. Barrett would go on to make two very troubled but beautiful solo albums (his song ‘Dark Globe’ alone is a strange lightning-struck tree somewhere on the peaks of English folk music) before decades of unbroken silence but you get the sense that he never recovered from that initial arc. And we never took the right lesson from it as teens, embarking on many years of decadence that had a cost in terms of health and sanity. In one sense, Barrett’s tale is a very real and tragic story of fame and mental illness and in another, it’s an example of how all the deepest tales we encounter as children are the ones with darkness as well as wonder. And they are the hardest to avoid because the deep dark Wild Wood is the most tempting of places to delve into.

Onyx – Throw Ya Guns

By our teenage years, on the edge of a rainy island perched at the furthest reaches of Europe, you had a choice of looking west, across the vast ocean, for music or east across a narrow sea. You were alien to both so take your pick. I should have been more inclined to like Britpop, given my love for Barrett, but most of it sounded like mockney oompah music and gave me the dry heaves. Through older brothers, we’d become obsessed with the degenerate sounds of America (Jane’s Addiction, Nine Inch Nails, Butthole Surfers, Mr Bungle etc). Hip hop was a huge part of that. So many of those records transport me now back to that time – long summers listening to g-funk for instance – but not all nostalgia is necessarily positive. So much of what we listened to, especially some of the really intense atmospheric East Coast sounds, takes me back to getting chased through building sites, hanging out on rooftops and tunnels, getting up to all sorts of shit (though harming ourselves more than anyone else). The memories are such that it’s always night, always approaching winter, lit by the yellow glare of streetlights, and there’s always some trouble just out of sight up ahead. I’d love to pick a song from an album like Enter the 36 Chambers or Liquid Swords that embodies that time but back then they were just great albums among many and we naively thought the next ones would be better. They hadn’t been canonised yet. The song that is like a time capsule for me is by Onyx. It’s got that murky production in the verses and that cheesy American football style chant in the chorus that was popular at that time but if I hear that tune, I’m still there, with the city lights below us, and the 21st century is just a whole lot of trouble up ahead, just out of sight.

Faith No More – Malpractise

I always liked Mike Patton’s misanthropic sense of humour and the way he’d point you towards music like Godflesh or Ennio Morricone. There’s a troubling reason I include this song though. It’s one of the heaviest songs on Angel Dust. It sounds almost industrial at times but there’s a section at the end with these crazed strings. The first time I ever listened to that album, I kept stopping it and rewinding it to listen to that bit. It sounds like the end of the world. I learned later it’s a sample of Dmitri Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 8 – to this day the single most terrifying piece of music I’ve ever heard. Dedicated to the victims of Fascism, it starts off slow and mournful, before bursting into this crazed danse macabre that clearly references the Holocaust. It was a reminder in the midst of our bloody little war that there had been much worse horrors elsewhere. As Masha Gesson puts it, you think you’ve reached rock bottom until you hear someone knocking from below.

In the summer of 1996, there was a standoff at Drumcree with thousands of loyalist Orangemen insisting on marching through Catholic areas. It got violent and it was one of those moments where everything seemed to be spilling into chaos and the prospect of all-out civil war. I was fifteen at the time and was hanging around the protests, as we had for years. Riots weren’t unusual. I remember running through a housing estate one night and there were missiles being fired and the sky was glowing red from fires and the end of this song, that Shostakovich snippet, kept going round and around in my head. I felt this exhilaration but it was also theatrical, like we were playing at being revolutionaries (the same way we’d whopped with recognition that the scenes that drive Axl Rose insane in the video of ‘Welcome to the Jungle’ are from riots in Derry), and it always felt theatrical until suddenly it would lurch downwards, like in a lift that’s suddenly falling, and you’d see people getting badly injured, cars on fire, manic chases through alleyways and backyards and the fear, the real cornered animal fear, would kick in.

One particular day, I was at a part of town where trouble tended to occur and you could feel something bad was coming and I had that song in my head again and something, not quite a voice but something told me to get out of there. I went home and I woke the next day to the sound of my mother crying. A lifelong friend of hers had been killed by the army at that same intersection. They’d drove over him in a military vehicle and battered those who went to try and help him. Violence is abstract. You can deliver talks about it and write studies on it but when it enters your life, it’s as if you, and you alone, fall through the earth. Northern Ireland was like that. It was all far away until it was suddenly too close – a gun in your face from a passing car and the laughter of those inside, a random terrorist checkpoint in the middle of nowhere and the nauseous panic of not knowing which paramilitaries they are, waking up as if from sleep to find you’ve been kicked unconscious on the street. And we were merely a bystander generation compared to the ones before. Yet, if your luck ran out… it was all far away until suddenly it was much too close.

The Beta Band – Al Sharp

Though I live in London and big cities are the focus of almost all my work, I’ll always be someone from the periphery and because of that my heart is with those from similar places, wherever on the planet that is. As much as metropolises have momentum, options and anonymity, they can also be black holes consuming those they attract from outside. Coming from a place that’s main export is its youth, it’s easy to resent the limitations of the provinces but equally the vampiric nature of the big smoke, and I often wonder what would these islands be like if all the opportunities were not centralised in one or two places. Growing up on the border with Donegal, an isolated enchanting place, I’ve an obsession with hinterlands cut off from the ‘mainlands’ and the unique cultures they produce. Suffolk is one example, another is Fife. Places that feel simultaneously self-contained and liminal. Places with secret histories, with huge skies and wild shores and the sort of boredom that, if it doesn’t drive young people to self-ruin, will drive them to creativity. The Beta Band were one such example. Listening to hip hop, dub, psychedelia in a place that felt like the edge of the world, I could emphasise with them. This song sounds vaguely like Gregorian monks in a space station, which they, and I, may as well have been living in. There are writers, artists, musicians in these space stations all around the world and so much depends on them.

Two Lone Swordsmen – Machine Maid

Four days into a sesh in a stranger’s house, having forgotten your own name and terrified of the sound of birds singing outside, you cling to the music like it’s the deck of a sinking ship and somehow, for the hours required, you stay afloat. Or you’re not in a house party at all but on a dancefloor in a dimly-lit club and the sound is making the floor vibrate and the walls melt and you’re shaking Andrew Weatherall’s hand and everyone is dancing like there’s no tomorrow and everyone is happy and everyone is dancing and you’re shaking Weatherall’s hand and everyone is still alive.

Pulp – Wickerman

Sumer is icumen in… I mentioned earlier that I didn’t care for Britpop but I make an exception, as everyone should, for Pulp. I wrote somewhere in Inventory that I felt like my teenage years properly began with the opening notes of His ‘n’ Hers. It was like a starting gun going off and the next few years unfolded in parallel with that band – the high and revelations of Different Class, the bleak but exquisite come-down and heartbreak of This is Hardcore. And that’s the way the three-act structure is supposed to work, except life isn’t like that. It carries on and you find yourself beginning the whole cycle again, somewhere new, somewhere far from home, and it keeps repeating over and over, different each time, different people and places. The Pulp song that means the most to me is this unfairly overlooked psychogeographic journey through Sheffield, where the narrator, to snippets of ‘Willow’s Song’, searches for fragments of the past. Except its not the past we’ve been uncovering all along on our wanderings out into the world but the future, “Wherever the river may take us…”

Inventory is published by Chattos & Windus in the UK and Ireland, [https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/111/1112803/inventory/9781784741501.html] and Farrar, Straus and Giroux [https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374277581] in the U.S.