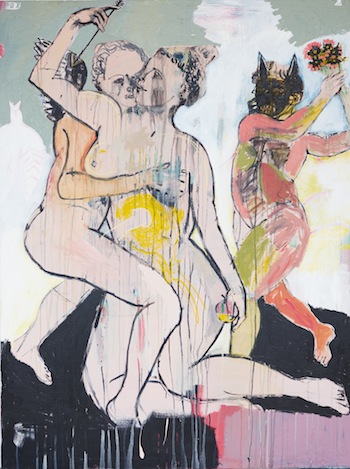

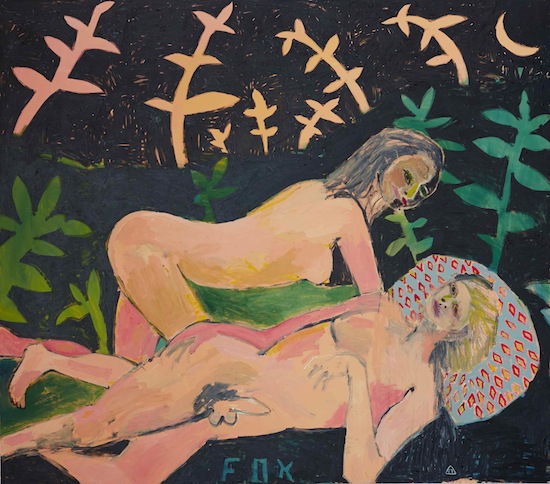

Danny Fox is a London-based painter, poet and musician, originally from St. Ives, Cornwall. His exhibitions, Song for Someone Else, Young British Alcoholics and this summer’s Bloom have over the years brought him a cult following, with his paintings of wild horses, delirious figures and enshrined beauties in great demand. Large canvases using iconography, Greek mythology and religious symbols recollect the styles of Otto Dix, Egon Schiele and Jean-Michel Basquiat, as well as complementing and challenging contemporary painters Peter Doig, Lucy Stein and Cecily Brown. Simultaneously vivacious and sensitive, stylish and studied, Danny Fox’s work continues to evolve, taking in ideas from the past as well as present observations and people, and exploring other media with consistent success.

Your book White Cake included various poems and short stories as well as paintings and drawings… tell us about how they came together and what they were about.

Danny Fox: I wrote most of White Cake in Africa, I was there for a couple of months building a school with my girlfriend at the time. I was away from my paints and I needed a way of getting it all down so I started writing. It’s mostly a journal that jumps into stories here and there. Some of the writing is about Africa and some of it is fiction based in London. It’s more or less about the end of a relationship. I added the horse paintings later once I was back on English soil.

What did the horses mean then?

DF: When I got back from Africa me and the girl broke up and I moved into a tiny box room. The only work I could make was on my lap as I perched on the edge of the single bed. So, I started making all these small paintings on paper so I could store them easily. One day I found this little model horse somewhere and began to paint it over and over again making it weirder and more colourful each time. I don’t know what they mean, but it makes sense to me now that it felt good to paint wild horses when I was in that little cell like room… At the time I called them "happy to have lived long enough to paint these beautiful horses, master" … Who knows, it wasn’t a happy time. It was around that time I decided to put them with the writing into a book.

How did the trip to Africa inspire you, particularly?

DF: I felt I needed to write it because I was having very conflicting feelings about what I was doing there. I had never been involved in charity before and I was questioning the whole thing but I had to finish what I had started so I used the writing as an outlet for that. In a situation that at times felt completely out of control I found great comfort in sitting down and tunnelling through it all by writing. Near the end of my time there I got robbed and actually lost about half of what I had written. Don’t get me wrong though it wasn’t all bad; we had some great times out there and I wish I had put more of that in the book.

Maybe that came out in the paintings though? There’s a tenderness to those pictures that offsets the stories and poems… Maybe overall there’s balance?

DF: Some tenderness, definitely some sadness. Women really like the horses, more so than men. I think of the horses as female mostly, at the time I was going to the White Horse strip bar and wrote some songs about horses/women:

Little ladder in her tights,

I’d like to climb up and die in a spiders web,

outside cigarettes are lighting up,

I’m tired of everything,

white horses sleep standing up

and white girls all sleep standing up.

Or another song:

Where there are horses there will be fences,

This isn’t a marriage this is a sentence

Still have a drawer full of your dresses

A book of wrong numbers and endless addresses

Have you done much writing since that trip?

DF: I recently finished a collection of poems called Dolphins which is just my favourites from the last year or so but mostly I’ve been concentrating on writing lyrics for my band Boss Universe, which is of course infinitely harder and takes a lot longer so it seems like I haven’t written much since.

One of your exhibitions was called A Song for Someone Else, and you’re in a band as well; are these paintings love songs? Do songs inspire art? What is the relationship between music and painting and love for you? How do they influence one another? What makes you do one and not the other?

DF: That show (A Song for Someone Else) was full of love songs and they were all for one person. Looking back, I think the work suffered because of that. Painting is a solitary act for me; I don’t need anyone around to make paintings. But to make music I rely on other people, which is good – that’s the main difference in painting and music at this stage. They are separate parts of my life really, like having two jobs, one in a bar, one in a lighthouse. Other people’s songs can inspire me, though – I always have music on when I’m painting.

What music, lately?

DF: I like to listen to a lot of classical music when I’m painting, the most simplistic stuff I can find. I like simple piano. Those Nick Cave and Warren Ellis soundtracks get played a lot in the studio… The Jesse James one especially. I like Cat Power a lot too. I sometimes use music as way of getting back to a certain time, dredging up stuff from the past and putting it down on canvas. Actually let’s not get into that.

Do you find that literature inspires your painting and vice versa? If so, which authors especially, or which poems or lyrics?

DF: I have been doing some big paintings inspired by Greek mythology lately so I did a bit of time in Swiss Cottage Library, reading up on those subjects. But generally it’s not as direct as that. I named one painting from my last show, Bloom: “Man on a cane seat throwing bread to swans” which is a line from Naked Lunch by William Burroughs. I don’t really need to be inspired by literature though. At the end of the day it’s colour and imagery moved around until it works.

There seem to be stories implied in your portraits and cautionary tales in the eyes of sprawling figures. Do you think of painting as a kind of storytelling? How do you explain the connection between narrative and painting (in your own work especially)?

DF: You can take something simple and make it feel complex and you can take something complicated and make it seem simple. I have no way of knowing what you are going to feel when you look at one of my paintings; I only know what I feel. If you can see a world within a portrait I would be happy with that. I don’t want to tell the story with a painting, though. I’m trying to get away from the story- from the beginning and the ending. I used to use a lot of words in the paintings but stopped because it created a narrative – or an answer to a question.

So are you going for a sense of immediacy, in being beyond past and future, beginning and endings?

DF: [Yes but] sometimes what seems like an immediateness might have taken a long time to get to, like the way Burroughs would cut up his pages and stick them back together to create abstract images, he still had to write the story first to get to the point where he could chop it up… The spirit of a painting is very hard to explain and articulate. I can’t say it’s not intentional because that is the mark I’m trying to hit, however I don’t feel I have much control over it. I make work all day long (some days) that doesn’t have it – the spirit, the shit, the holy ghost – then it suddenly appears and that painting might end up being kept. It’s not all magic, but there is a bit. That’s what I was saying about Burroughs: you still have to write the thing before you chop in into a thousand pieces. Yes, painting can be like poetry but as somebody who creates both I feel the necessity for both so they cant be that similar. Sometimes I think it’s as basic as not wanting to get dirty. Sometimes I just want to sit and write at a clean table and not get paint all over my hands. A lot of my words come to me when I’m out and about as well, riding the bus or sat in the pub. I went through a stage of going to a strip bar called the White Horse at lunch times and did a lot of writing in there. I mean, they were fine with that but I don’t know how they would feel about me setting up the easel.

You mention Burroughs again; do you identify with his process of cutting up pages and sticking them back together, and so on? Because that’s more what poets tend to do, as a process, which makes me think poetry and painting are quite similar as a mental process. And with Burroughs that seemed to be a statement, as well, against much other literature, and a statement about how we (or he) experienced life, memory etc. There’s an inherent rebelliousness about the way he restructured stories to the point of abstraction. Do you think of your own work in that way, or is it more of an instinctive approach perhaps beyond explaining this way?

DF: Its nice to live in that moment of abstraction, he probably did it so he could just be out of his own mind for a while, that explains why he did a lot of other things too and why we all do them, whether it be heroin or Corination Street – its just a way out of our own boring shit. Some of my work is very instinctive, some of my favourite things I’ve ever done are just two minute sketches, nothing is better when you get it like that so quick, then other work takes months. For my last show I worked on a series of still life flowers that were done over a 6 month period where I was taking painkillers for physical pain. For the whole time I felt dried out and strange and had to sit at my desk painting small pictures rather than standing up carving into the big ones like I’d prefer. What I’m trying to say is there are ways to paint a novel and ways to paint a poem. I don’t think of myself as a rebellious artist, a lot of people have said that about me because I came from Cornwall and choose to paint people in what they considered to be an urban style instead of Cornish landscapes. I’ve never agreed with them. It’s bullshit. I guess I can identify with that cut up technique a bit, I’m looking at a painting I’m working on now and you can see all the layers from previous efforts coming through, I’m not thinking about them anymore but they are still part of the painting. If this painting was a cut up poem it would say “Eyes in white jungles sing like bone ashtrays.” That would make perfect nonsense if you could see it.