Thirteen years ago, Dan Richards climbed through the window of my room at our university halls of residence. He introduced himself to me and my then-girlfriend, played my guitar, and enthusiastically discussed the band Ash, a poster of whom adorned my wall.

I was faintly bemused; we became friends, co-hosting an enormously self-indulgent student radio show and occasionally collaborating on stories for the arts section of the student newspaper. One such assignment saw us dispatched to rural North Norfolk. We were to talk to ‘King Nicholas’ Copeman, a witty, evidently quite bored man who had declared his caravan park his kingdom, changed his name by deed poll, pulled off some fantastically silly ‘royal’ stunts and written a book about it. I was nervous about the interview, but not Dan. “It’ll be fine,” he assured me. “We’ll just turn up and have a chat.”

—

For more than half the time I’ve known Dan, he’s been working on ‘the book’. Unusually, ‘the book’ started when he whimsically decided to build a six-metre replica of the Hindenburg in the bar of the Norwich School of Art & Design, where he was studying for an MA in creative writing. The airship was a labour of love, technically challenging and greatly time-consuming, though building it in a bar had its consolations: I remember spending a long weekend doing college work on my laptop while he measured, sawed and glued the zeppelin into shape. Frequent breaks for Guinness and table tennis served us well.

A Bill Drummond artwork hung in the bar: a large canvas bearing the legend ‘GET YOUR HAIR CUT’. It piqued Dan’s interest: he told me he was going to seek out Bill for “a chat”. Later that year, he conducted another chat, this time with the letterpress printer Richard Lawrence. Richard worked with the artist Stanley Donwood: Stanley’s contact details were duly sought…

Seven years later, ‘the book’ has become The Beechwood Airship Interviews: an unusual and inspiring examination of what can loosely be termed the creative process – a project fired by a sense of disillusion with arts education, but equally by a passion for craft and communication. The book collates Dan’s visits to artists, actors, writers, comedians, musicians, photographers and craftspeople, all of whom toil at what he calls “the same creative coalface”. In it, the painter Jenny Saville talks about diseased lungs and mixing paint; Manic Street Preachers singer James Dean Bradfield discusses Simple Minds and where he sits to write music; photographer Steve Gullick mourns the scarcity of film and thrills to the challenge of mundanity. Other subjects include Dame Judi Dench, Vaughan Oliver, Jane Bown, Stewart Lee and Robert Macfarlane.

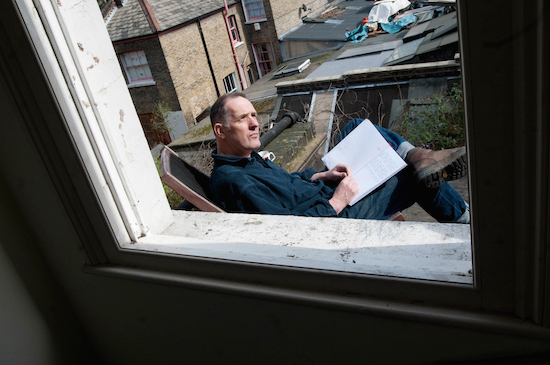

Now I am interviewing him about interviewing them. As Dan made a point of visiting his subjects at their places of work where possible, it seems appropriate to travel to his home in Bath. We arrange to meet at midday, but I leave late, get caught in Saturday traffic, and eventually arrive at 1.30pm. I realise I have used our friendship as an excuse to be unprofessional. Poor form.

I’m sorry for being so late.

Dan Richards: That’s okay, it fits in with the spirit of the book! Also you’ve brought cake so I don’t care.

Were you late to any of your interviews?

DR: I was late for Robert Macfarlane the first time I met him, in December 2009. It was very cold, and my train from Norwich to Cambridge, where I was meeting him, was delayed in the snow so I was very late – I arrived at about half one having said I’d be there at noon. [I have unwittingly echoed this! A good sign, perhaps.] When I got there the iPod I recorded everything on had no battery, I was completely underprepared, and afterwards my notes were completely indecipherable. It was terrible.

You mention this episode in the book. He described it as “the most inept interview I’ve ever been involved in”. But that didn’t put you off…

DR: Well fortunately it didn’t put him off – we remained in touch, and we ended up working on the Holloway book together. [Dan co-wrote Holloway with Robert Macfarlane and Stanley Donwood, mid-way through the process of writing The Beechwood Airship Interviews. Richard Lawrence, another interviewee, was enlisted to print the initial run.]

If you’re turning up for an interview you have three jobs. Prepare, turn up on time and have a working Dictaphone. At various points in the book I did spectacularly fail at one or all three of those things. But sometimes, even with them, it doesn’t go well… When I interviewed Geoff Dyer for a different project, it went so wrong. I turned up with all these notes, on time, with a working Dictaphone, and it recorded nothing but verbal diarrhoea from me, trying to find something sensible to say to this great writer, and him desperately trying to help me, but unsure what I wanted. “The journalistic equivalent of paying for a whore, but asking if you can just have a chat,” as he put it, “because it’s really not working out.” And then he bought me some lentils – possibly to shut me up.

You’re a habitual interviewer and recorder. Even before you started this project, I remember you taping a conversation with Bob [Dan’s grandfather] about him working on the travelling Post Office train. Where does this urge to document come from?

[Dan wonders off, hauling a couple of large artists’ sketchbooks from a shelf on the other side of the room. They are scrapbook-diaries, two of the many he has kept since secondary school. In this university-era example, I recognise my own writing – earnest notes to accompany a Manic Street Preachers mixtape I made in an attempt to convert Dan to the cause (successfully, as it turns out). Another page reveals a card I made: a photograph of Morrissey framed by the words “HAVE A SHIT CHRISTMAS”. This pleases me: I had forgotten about it.]

I like to keep things together and to record things. A fear of loss is part of it. People have interesting things to say and you don’t want to be reliant on your ability to remember things in that moment. I remember my grandfather trying to record his father’s memories of the First World War. And Bob talking about the mail train – these are great stories. And these scrapbooks and diaries, the idea of recording the day-to-day, that’s always interested me too.

How did you go from building an airship to writing a book?

DR: The airship came out of the idea that you should be free to dive off at tangents, if you’re at an art school. I built it as a way of documenting the fundamental lack of connectivity and joined-up thinking within the art school at the time. When I left, I went out into the world and used the same sort of thought process – of documentation and interrelation – in a series of encounters with artists who were to my mind interrelated, because they were all working at the same creative coalface.

Was there a point when you realised you had enough interviews for a proper project?

DR: I think when I spoke to Jenny Saville it became a thing, because I realised I had four or five world-class artists who were talking to me in a way that they hadn’t, as far as I had read, spoken about their work elsewhere. And I was getting access and interesting stuff from them to the extent where I thought ‘well this deserves to be a book’. If you’ve got good stuff you should do something with it.

How did you contact people?

DR: I wrote nearly everyone a letter. I went through the university Vaughan Oliver was teaching at; Sheryl Garratt I went through the writers’ yearbook or something. I wrote to Jane Bown having discovered her address by going through the listed building register. I found her under her maiden name – she’d asked to have her wisteria pared back. There are ways to get people’s addresses.

What can you tell me about your interview technique?

DR: I tried to allow people to talk. Hopefully the book feels more like a conversation than a Q&A. There’s some great stuff in Judi Dench’s chapter about acting, and how she disagreed with what Bill Drummond said about his father being an actor when he was in the pulpit, and that all flowed from a silly question about Glastonbury Festival.

Richard Herring got Stephen Fry to open up about his suicide attempt during an interview in which he also asked him if he’d rather have a hand made out of ham or an armpit that dispensed sun cream.

DR: Stuart Maconie used to do a similar thing at Q magazine: he’d ask Kate Bush about her new album, but then he’d drop in a question like ‘when were you last in a physical fight?’

One of the things you say in the book is that you’re not a journalist and that you don’t have a list of questions…

DR: Well, not editorialised questions. If you’re turning up to interview Judi Dench, as a rule you ask her if she’s sad to have left the James Bond franchise or about her personal life; what a journalist wouldn’t do is ask her almost exclusively about the craft of acting.

But though it wasn’t the usual journalistic angle, you still had an angle.

DR: Yes, but at the time of the interviews I didn’t have a publisher saying ‘we want this sort of book’. I just wanted to talk to them for ‘the book’: this amorphous, tangential thing. Also, it’s worth saying that I spoke to all the people in the book because I like what they do, so it’s in my interest, from that point on, to make them and me look good… by which I mean it’s all my fault, I’d like to make that perfectly clear. Apart from any spelling errors, which my publisher’s proofreaders really should have picked up.

You conducted the interviews often at the person’s place of work. Why?

DR: During the process of building the airship I went to see Colin Henwood and Dick Way at their boatyard in Henley-on-Thames, and that’s where I began to realise that the way people spoke about the way they worked, in the spaces where they worked, was different from the way they spoke about it elsewhere, because they were surrounded by their stuff and they could refer to things. I felt people would probably give more of themselves away when they were more engaged with their work. The work is a form of expression, and through it they reveal themselves.

During my gap year I spent a bit of time working at Guitarist magazine, and so go you’d go and interview somebody like Mark Knopfler, and then afterwards they’d sit for a photoshoot with their guitars, and they’d start talking in a very different way – they’re interacting with the thing that they do, as opposed to talking about it in an abstract sense.

There’s a palpable sense of excitement from you when you meet these people.

DR: Yes, I think too many people try to be cool. They try to hide the fact that they’re excited to be in these situations. You have to seize the initiative. Going back to the Guitarist thing, if you’re having a chat with Graham Coxon and he’s there and he has some guitars, why not ask him to show you how he plays something? He probably will, and he’ll probably be happy to have been asked. It’s exciting, it’s magic. You should ask! I get frustrated with people who are scared to put themselves out there and make idiots of themselves and ask and say what they mean. I do that, often to my detriment, but I am sincere in not being afraid to make a terrible tit out of myself, constantly.

You’re wholehearted about it.

DR: Nothing ventured, nothing gained – I think that’s important. You’re speaking to people because you think they’re interesting and will make sense in the context of the book, but on some level you’re approaching people because you find them and their work attractive, and you want to spend time in their company. So of course it’s exciting and it would be misleading not to reflect that.

What was it like talking to seasoned interviewees versus people who hadn’t been interviewed much?

DR: I get an enormous sense of rage when the seasoned interviewees speak to somebody else and give similar answers to similar questions I have asked. Judi Dench is a classic example, but she’s interviewed so much – saying she wants to be the Afghani woman who tightrope walks and turns into a dragon – that’s come out and that’s in the book. But she’s probably said it with her family, and her agent, and a couple of interviews.

She probably knows that’s a good quote; she’s being kind to her interviewer.

DR: Absolutely. But I think ‘Ah, why!? Why can’t you just keep the gold for me!?’ But yes, I tried to steer clear of the obvious questions. With Judi we talk about bad interviews and the questions she doesn’t like to be asked. It’s the same with the Manics. We talk about Richey Edwards, but not in a ‘isn’t it sad that he’s disappeared?’ sort of way. [This is true: Dan jokes with Nicky Wire that the band ‘won’t shut up about him’.]

The book is as much about the process of interviewing as it is about the interviewees. And it’s about my process, which is learning how to write a book while writing a book. It’s a book about thinking, and to write clearly you have to think clearly… which is the reason it took seven years.

Did you ever get nervous? I remember you being pretty relaxed when we interviewed King Nicholas in Norfolk…

DR: I’ve always been fairly laid back about meeting people – that’s not to say there haven’t been occasions when an encounter hasn’t been a fucking disaster! Geoff Dyer for example… poor Geoff. But I’ve never been worried or hobbled by the idea that I’m not worthy or qualified or capable of turning up and engaging with somebody just because they’re a Dame, or a hero, or a Dame and a hero, or a man with a crown and pretend title who lives in caravan overlooking the North Sea.

You were saying earlier there was a point where you’d turn up, have a cup of tea, and then the interviewee would eventually say ‘so… what do you want?’.

DR: Yeah, the parameters need to be set, and at the end of an interview, you leave. Unless the relationship has moved on to a point where you can go down the pub, or swap numbers… It’s alright to be an odd proposition to the point where you get the interview, but there are limits.

But you want both, right? The structured stuff and the cup-of-tea chat.

DR: Yeah. The Manics interview ended when Nicky Wire came back from an afternoon shopping in Cardiff to find I was still talking to James Dean Bradfield and playing Smiths tunes on his Fender Jag – mucking about, basically. I remember he said ‘fucking hell are you still here?’ At which point I thought ‘Yeah, it’s been four hours, I probably should go…’

Let’s move on. Transcribing. Hard work, eh?

DR: Hellish.

[I understand there is technology that can translate voice recordings into written words. It sounds fantastic, but while I empathise with Dan’s description, as I transcribe this interview I am reminded that I somehow find the whole miserable experience useful.

I curse my rambling questions, my mumbly voice, my stupid laugh, and the times when I miss the opportunity to ask a good follow-up question. I am disproportionately furious when he repeats or refines a point – ‘no! you already said something I can use on that subject!’.

But. The ebb and flow of the conversation – and the nature of it, of course – allows me to ponder the structure and edit of this piece. It is part of my process: The interview veers away from the course I had plotted, revealing its useable material in a way that suits its subject, rather than me – as it should be. As I (feverishly) write this sentence, I have transcribed 7,105 words…]

What’s roughly the amount of information you had to work with?

DR: I’ve got a playlist here on my laptop called ‘book’ and it’s 3.8 days long. That’s all the interviews, including those with people who didn’t make it into the book, but I still transcribed everything.

How conscious were you of editing what people said to fit a narrative?

DR: You make the spine of the book the journey – the ‘sense of quest’, my agent calls it… They were big in the Eighties, I think. But yes, you want to create some sort of journey so the reader is encouraged to follow. The person who guides them is me, because I’m in every chapter. I’m like Richard O’Brien.

You’re very like him, yeah. Always playing the harmonica…

DR: Always playing the harmonica, dancing ahead, you’ve met my mum, she told you that riddle… I mean obviously the book was curated. It was difficult to edit, because a lot of what people said was wonderful. It comes in at 531 pages – an Australian test score – and it could have been a lot more.

But actually, editing is a very useful skill, and an interesting thing to develop. I think making a book is like crafting an object, it’s like sculpture in a way. You have to keep the essential element of what you’re doing and get rid of anything unnecessary. Everything in the book serves a purpose. There are tangents, but they’ve been put in the footnotes, so you can choose whether you follow it or not.

They’re like Choose Your Own Adventures, but without the bit where you take the wrong turning and are instantly killed by a dragon. Anyway, some of these footnotes feature other interviewees…

DR: Yes. The film-maker Gavin Rothery didn’t fit because I’ve got Judi Dench to talk about films with. Though he has got one hell of a footnote in her chapter. The beginning of it explains a lot: “In the course of many conversations at his Hampstead flat, he explained the massive amount of work that goes into getting a movie made. In the end I amassed and transcribed over 20,000 words but couldn’t fit them into this book; they’re the beginning of another great book in its own right, though, and I hope to pursue the idea in the future.”

Everybody in this book is of a slightly different nature. You might have two photographers, but they fulfil very different roles. John Parish and the Manics in the same book: they’re obviously very different but they would eat into each other’s process. Freya Cumming, a silkscreen printer in Bristol, was wonderful, but Richard Lawrence’s chapter was stronger.

One guy I just didn’t get on with. At the end of interviews I would always ask ‘if you were me, who would you talk to next?’ And when I asked him that he said ‘Oh I don’t know, I wouldn’t want to waste anyone’s time’. I thought ‘well, you can fuck off’.

There’s a theme of destruction: the Manics considered burying Journal for Plague Lovers; the KLF burned a million pounds; Steve Gullick considered destroying negatives of his Nirvana photos. And you burned the airship. Why?

DR: The airship became the book – it served its purpose as something to inspire. I didn’t want the art school to have it, because they had abandoned everything it embodied. They closed the bar where it was on display. It was built for that space, and the space had changed – the art school managed to destroy the purpose and ethos of the space to such an extent that the airship, any art in fact, was no longer relevant, loved or wanted. So I sent it out in a blaze of glory. And it’s a homage to Bill Drummond burning a million quid. I’d been inspired to make a statement.

It’s like TS Eliot said [Dan removes a post-it with a scribbled quote from his wall]: “Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood”. Some art does that. The act itself said something, even without knowing the history or context of it. I made a replica of the Hindenburg out of beechwood, and I’ve taken it out to a field in Norfolk and set it on fire. That should be a starting point for people to go… ‘what?’

The Beechwood Airship Interviews is out on 31 July on The Friday Project/HarperCollins