It’s been longer than planned since the last round up of comics, but that means we’ve got a build up of especially interesting releases this time. Elder statesmen of the indie comics scene Daniel Clowes and Chester Brown both have new books out, the always exceptional Youth In Decline have the next edition of Frontier, Avery Hill’s meteorically rising star Tille Walden’s second book is reviewed (and her third is on the way), we’ve excellent first releases from Nick Drnaso and Ben Gijsemans, and more.

We also have some home grown talent offering work for you to read. Our own Aug Stone has a new comic online, written by him and illustrated by Mikey Georgeson, the singer of David Devant & His Spirit Wife. You can find it <a href="https://issuu.com/morningdrawings/docs/the_knowledge_of_princesses.pptx/c/spzr12x”=”out”>here. Jenny Robins has also collected some of her comics work on her site. Both links are well worth your time.

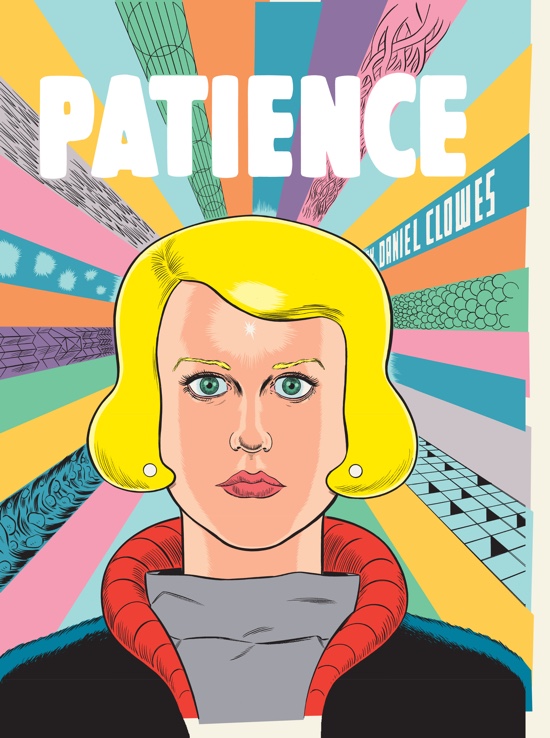

Daniel Clowes – Patience

(Jonathan Cape – UK / Fantagraphics – North America)

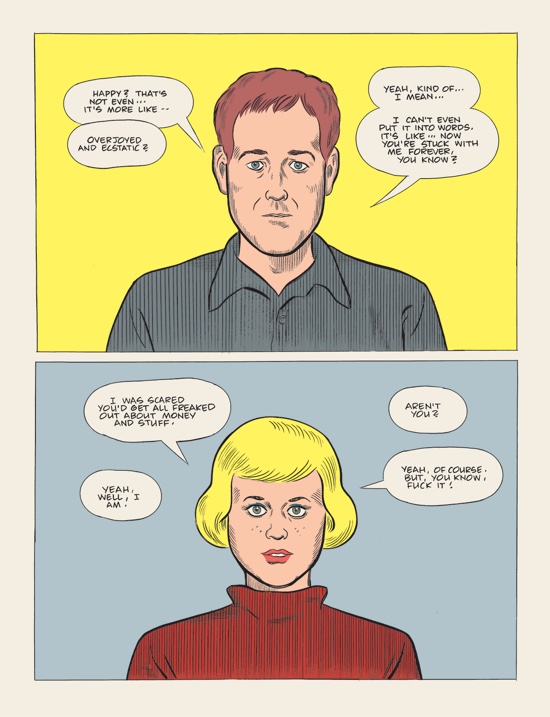

Daniel Clowes’ new book Patience is upon us, with another cast of unhappy, ill at ease characters. We first meet Patience and Jack in 2012, shown in silhouette as they take a pregnancy test. When we glimpse their faces they are in half page shot-reverse-shot panels, staring back at each other (and us) uncertainly, hopefully. Pretty soon we start to get a sense of some serious personal baggage, with Patience in particular. They seem more than a little misanthropic, united by their loathing of others. The day they find out they are pregnant Jack remarks “I don’t want to hang out with other people. I only like you and the baby”. Patience agrees, and adds “God, I’m just so relieved about your job. If we had a little more money coming in, everything would be perfect”. This is a Daniel Clowes book, so we know it is not true. If they had more money, they’d have more money but they’d still be the same fucked up people. As for the money, Jack’s not been entirely honest about his job or job prospects, telling her he’s been offered a more senior position while in fact he no longer even works for the company, but hands out porno flyers on the street. It’s a risky lie when you have to walk the public streets in potential proof of your deceit, but in any case this is incidental, as when Jack returns home the next day he finds Patience has been murdered.

From here Clowes picks up the pace, with years passing like panels and then we are in 2029. The Jack of the future has grey hair, Terminator shades, has yet to come to terms with his past, and few qualms about taking it out on anyone who antagonises him. Obsessed with trying to find out who killed his wife, before too long Jack acquires a method of time travel and is back in 2006 trying to uncover clues. The problem is, he’s pretty unstable, prone to fits of violent rage and thus we find ourselves facing the Back To The Future question, what will be the impact of his actions when travelling back on his own timeline? One thing’s for sure, he lacks the self control to stand back and not interfere, so there will definitely be some consequences.

Many Clowes trademarks are evident – his distinctive, visually retro art and colour schemes, repeated images of the characters looking straight out at the reader, a woman with a short blonde bob (a common character archetype for him) and an exploration of masculinity. He often obscures speech bubbles, by overlaying them with square narration blocks or by pushing them off the edge of the panels. This mirrors the way our internal monologue is more important than our external dialogues, and reflects a dominant theme in Patience, the impact of secrets on relationships. Compared to some of his work, there’s less humour and more anger, with frequent bursts of violence. As the time travel escalates the book heads towards entropy, gripping us to the very last panel and reminding us just why Clowes is held in such high regard. This is an essential purchase. Pete Redrup

Chester Brown – Mary Wept Over The Feet Of Jesus

(Drawn & Quarterly)

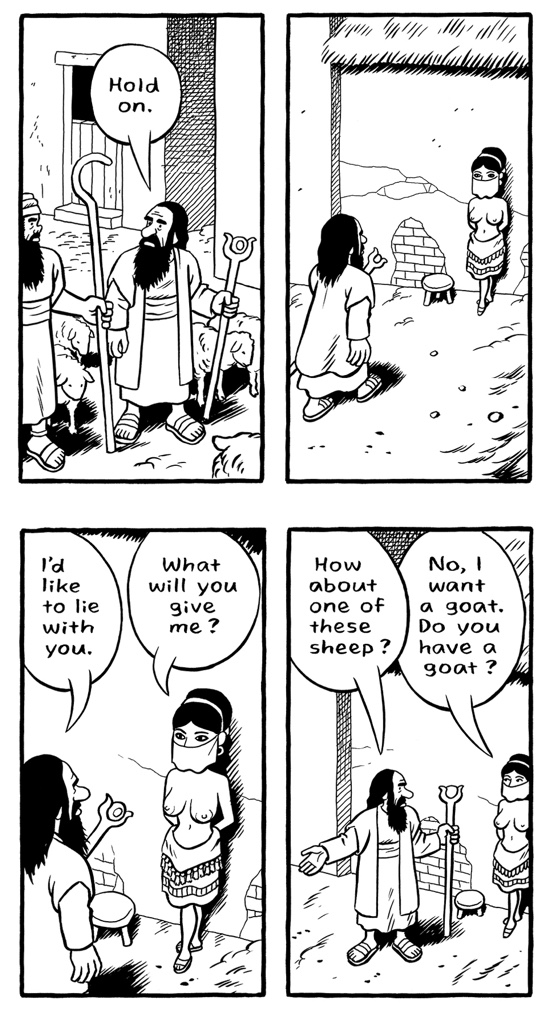

A new Chester Brown comic is always an exciting proposition, and a relatively rare treat. Mary Wept Over The Feet Of Jesus (a title that will take on a different meaning once you’ve read the book) is an account of prostitution and religious observance in the Bible. This follows on from 2011’s Paying For It, a disarmingly frank account of Brown’s own use of prostitutes and argument for sex worker rights. The format here is one with which his readers will be familiar – the comic narrative is followed by lengthy handwritten notes and references providing explanation and adding depth to his argument.

The main body of the book consists of a series of Biblical stories, starting with Cain and Abel. Some are accounts of women who were prostitutes, and some of women who were sexually forward. Some focus on men who slept with prostitutes, and the first has no references to sex at all, but explores ideas of religious obedience. There are a couple of parables which address more than one of these themes, and there’s also an account of Matthew writing his gospel. Many of these stories are presented dispassionately and without explanation (until you get to the notes, at least), but by the end of the comics section a clear thesis has emerged, explicitly stated in the last two chapters.

Brown’s art demonstrates such mastery of his talent. His pacing is flawless, and the skilfully crosshatched panels and characteristically impassive characters match his restrained and subtle storytelling, where hair flows but emotions do not. For example, comparing the story of Tamar to the R. Crumb version, this is pretty minimal, with a blank, dispassionate presentation. God’s violent killing of Onan in Crumb’s account is replaced with a simple ‘Onan dies’ panel – we see considerably less smiting from Brown’s God as that’s not relevant to his argument.

Once we’ve read the 170 pages of comics, we get to the handwritten notes. There’s a typically open account of his own religious beliefs and his gospel interpretations over 20 pages, followed by a 75 page notes section (which includes the story of Job as a comic) and then a bibliography. This adds weight to his argument, but I’d imagine many will skip or at best skim it. In this unique work which proposes that God prefers free thinkers to the blindly obedient, and that many key Biblical women were sexually forward or sex workers, Chester Brown reminds us that he is a truly original voice in comics, who uses his immense artistic and storytelling talent to propose carefully thought out, challenging ideals. Pete Redrup

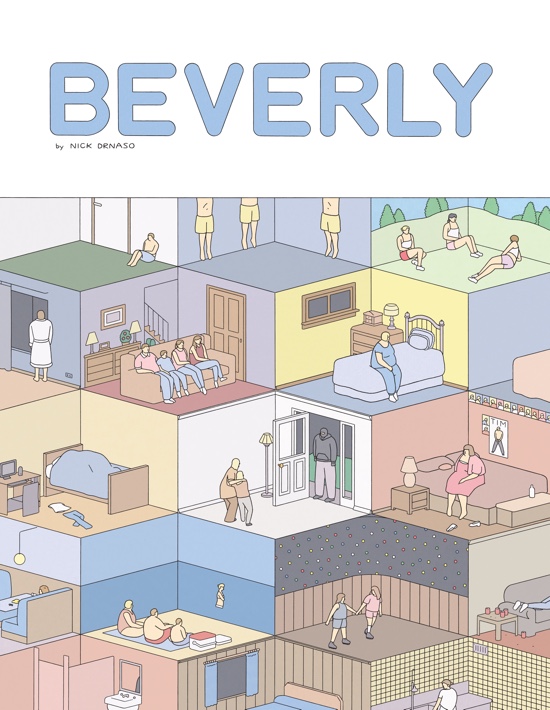

Nick Drnaso – Beverly

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Beverly is Nick Drnaso’s debut full length work, and a very impressive one at that. The superb Escher-like cover showcases both his deceptively gentle pastel palette and the problems – alienation, loneliness, sexual confusion and more – that lie under the suburban lives he depicts. Inside there are six chapters, with some characters appearing more than once, but which can all function as standalone stories. His chunky characters hide behind mask-like faces with scant details, leaving us to speculate on their internal voices.

In The Lil King a family of four go on a trip to Massachusetts to spend some time together before the children return to school. Tyler will be going into the sixth grade, while Cara will be a high school senior. The parents are full of cheer, returning to the place where they got engaged 25 years ago. The children, however, are less enthralled; there’s a palpable sense of disconnect between the generations. While the parents babble on, the children are silent for pages, and Tyler never speaks. He appears again in King Me the final story as an adult, speaking normally, but for now he is totally silent. The parents colour everything with their happy reminiscences, while the boy entertains darkly violent and sexual fantasies. It’s ambiguous about how he feels about them, and the result is both chilling and yet also blackly comic like a Todd Solondz film. In another standout story, Virgin Mary the expertly structured narrative demonstrates Drnaso’s considerable skill as he lays out depressingly plausible events based on an incident from his own high school.

The artwork throughout is clean and precise, with lots of space. Visually, the influence of Chris Ware can be seen, but this is distinctively Drnaso’s own voice in both the art and the storytelling. The combination of the repression and uncertainty the characters feel is echoed in the numerous panels that are wholly devoid of people, showing just places but no life. Beverly is an accomplished graphic novel, and is highly recommended. Pete Redrup

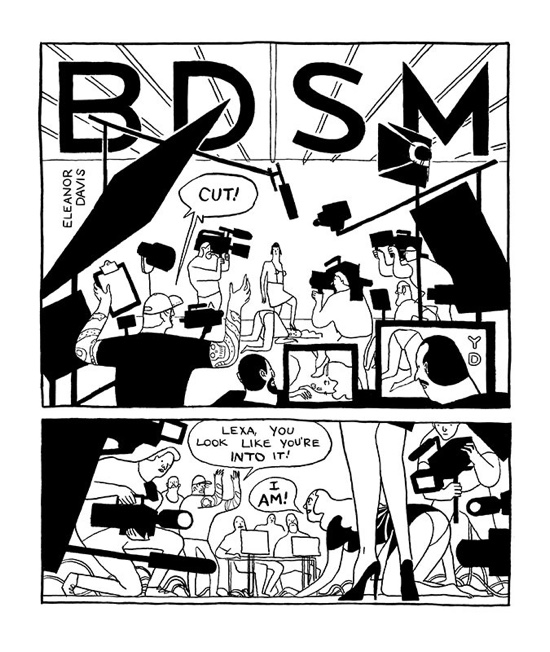

Eleanor Davis – Frontier 11 – BDSM

(Youth in Decline)

Youth In Decline’s Frontier monograph is back with a new issue by Eleanor Davis. BDSM opens with a two shot, a mistress-maid scenario with a strong sadomasochistic element. As we reach page 3, we get the title panel, and with a cry of ‘cut’ and a pull back we see that we are on a porn film set, complete with multiple cameras, lights, monitors (one of which shows an earlier panel) and a crew. The effect is impressive

What follows – on and off set – includes a power play about whom we can expect to be submissive. After sub actress Lexa fetches drinks for the (male) crew, dom Victoria spills coffee on someone’s boots but neither cleans it up nor thinks Lexa should do it. That’s not OK, it should be Mercedes’ job, whoever Mercedes is – her status is obviously so low as to not be threatened by such work. There’s some driveby focus on the male gaze, but mostly on the relationship between the two actresses, with some brilliant dialogue (“Ahh, this is so psychological! It’s, like, so sadistic not to hit me right now!)

This is a complex, rich but above all subtle comic, maintaining Youth In Decline’s unbroken run of excellence. Pete Redrup

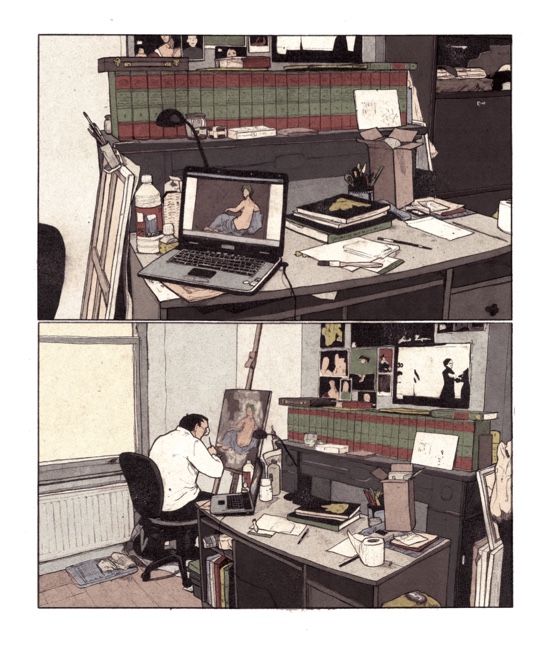

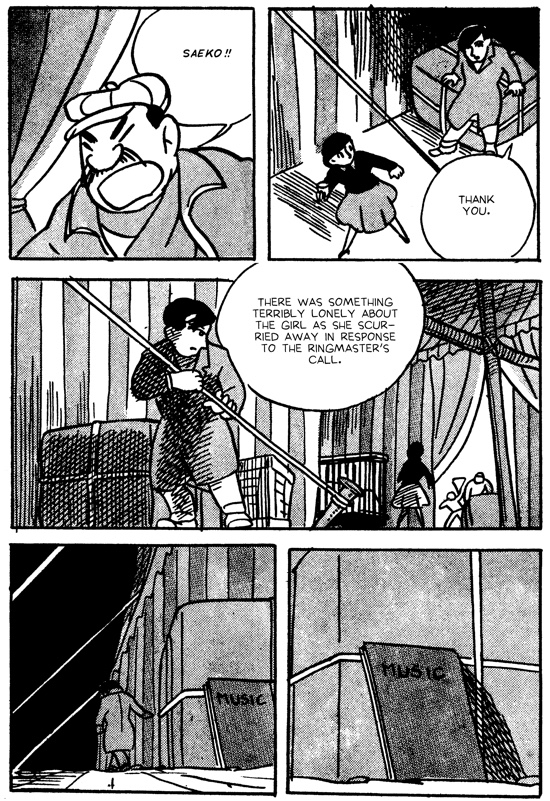

Ben Gijsemans – Hubert

(Jonathan Cape)

Hubert opens with the first of many drawings of famous art that I am insufficiently cultured to be able to identify. Ben Gijsemans has no such limitations, however, and does an excellent job of representing both paintings and the buildings which house them. His interior and exterior work is highly skilled, and he has a talent for short runs of panels that zoom in on details of sculptures and paintings, as well as architectural features.

Mr Hubert is an introverted man, whose only apparent interest is visiting art galleries, taking photos of paintings, then recreating them at home. He rarely speaks, and many pages go by without dialogue. If he does talk, it tends to be about art, and he certainly doesn’t seek out human contact. This is in contrast to his landlady who makes several attempts to entice him into helping ease her loneliness. Almost exclusively, Hubert’s only interest in women are those whose images he recreates at home – his focus is on people who are not real, not present. He only consumes cultural artefacts from the past – paintings, Chaplin films – apart from newspapers, which he reads as he eats alone in his room. The repetitive actions, and depictions of this, combined with the fact that so few panels contain dialogue, give a curiously meditative effect, like a series of snapshots of Hubert’s life. Through the repetition we gradually come to some awareness of the fact that whilst he is obsessed with art, he’s unable to relate to the reality of what art depicts, drawn into particularly sharp focus in a sequence with his landlady and a reproduction of Édouard Manet’s Olympia towards the end.

The book has an interesting aesthetic, very painterly (not just in the numerous images of paintings) whilst realistic in the depiction of architecture and infrastructure. Hubert himself is physically plausible in every respect apart from his glasses, which appear to have come from the lugubrious range at a discount optician, and perfectly complement his slope-shouldered demeanour. His depiction is kindly, not pitying, and there is even a suggestion of his first smile in the final panel as he starts to paint his own passions rather than those of others. This is an original and distinctive work, undeniably beautiful and thought provoking. Pete Redrup

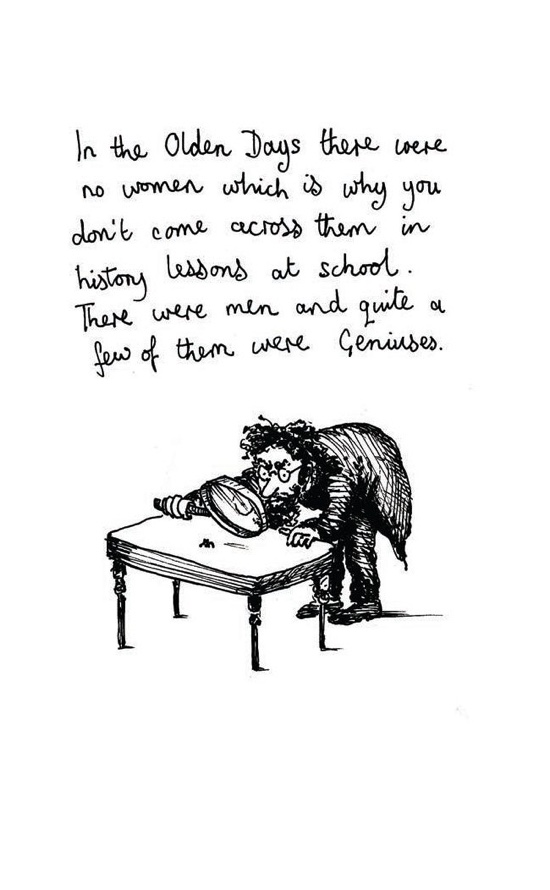

Jacky Fleming – The Trouble With Women

(Square Peg)

Fucking hilarious. The Trouble With Women is a wonderful, wonderful book. Jacky Fleming’s biting wit leaps off the page as she repeatedly shows men with their supposedly bigger brains actually unable to even recognise any female achievement. Or even observe anything correctly about women. Not that this has stopped women from achieving megatons more than given credit for, and credit must go to Fleming. I can’t recall the last time I literally laughed out loud so many times whilst reading. Aug Stone

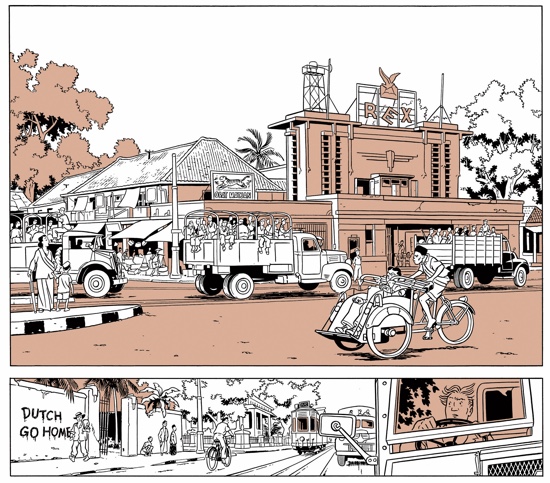

Peter Van Dongen – Rampokan

(PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama)

Peter Van Dongen is a Dutch comics artist with Chinese Indonesian roots which he wonderfully explores in this collected edition of the two Rampokan books (Java and Celebes), available now for the first time in English. The story centers on 24-year-old Johan Knevel travelling back to Celebes, the island of his birth, in 1946 at the end of the colonial era. Tensions between the Dutch and Indonesian people are running unspeakably high, setting the tone for the action. For this is a book filled with political intrigue, terrorism, black marketeering, racism, sex, and murder, all underscored by the ghosts of animal spirits and primitive magic. Rampokan itself is a Javanese tradition where captured tigers and panthers are ceremonially slain at the end of Ramadan and echoes of this ritual haunt the pages. The story is also charged with emotion as, in a world where everything has changed, Knevel ceaselessly hunts for Ninih, the maid who raised and cared for him as a child. Van Dongen’s art is really something to behold in all this. One marvels at how much he manages to convey on the page, where the main action is often set within larger scenes depicting a fuller sense of the life of the country, all deftly drawn. It’s a book rife with deception too, fitting for a world so erupted, where all this duplicity – of character, of feel, of the country itself – seems the only way to not drown in all the turbulence.

Rampoken is available by emailing the publisher at budidaya.sg@gmail.com . Aug Stone

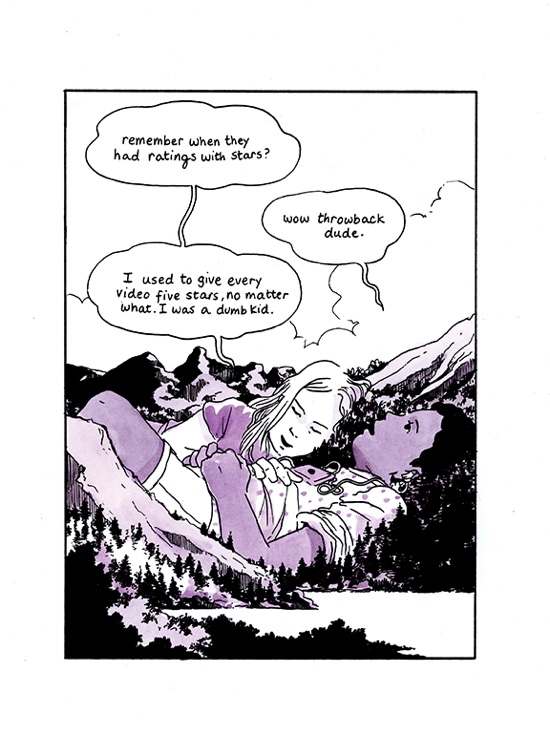

Tillie Walden — I Love This Part

(Avery Hill)

The central poetic metaphor in I Love This Part pictures the protagonists as giants, vastly out of proportion with the beautifully detailed landscape background in which they lounge, walk, talk and generally hang out. This contrast of the trivial with the epic perfectly evokes that heart bursting enormity that is first love. A timeless tale, this is anchored firmly in the present by the young characters’ use of technology and references to contemporary media platforms: texting, emailing and sharing songs on their phones. The use of music as a point of connection and emotional resonance within the story highlights the atmospheric and rhythmic qualities to the visuals and narrative, so that the whole comic could be seen as a love song itself, the kind that you listen to over and over again. In fact, as soon as I finished reading I Love This Part I flicked right back to the beginning and read it again. It’s quite short and is not broken into panels, so that the full page images have that dramatic impact which are sometimes very simple and focused and at other times extremely detailed, again reminding me of music and its wordless emotional power.

The fact that the teenage love story in question is between two girls of different ethnic backgrounds is at once irrelevant and hugely important. While the emotions expressed are universal, tension is created by the early implication that theirs is still a love that dares not speak its name:

“can we ever tell anybody?”

“probably not”

This highlights how far we still are from this young love story really being seen as as natural and normal as it feels from the inside. When stories are less often told they become in danger of being read as emblematic for whole subcultures, but this is the fault of society, not creators such as Tillie Walden. And this story of young love is not the perfect story of what we would perhaps like to think contemporary queer teenagers experience. But it’s also not really about that. It’s just about how it feels to be young, and to feel that centre of feeling that is the biggest and smallest thing in the world at once. Jenny Robins

Yoshihiro Tatsumi – Black Blizzard

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Black Blizzard is essentially about movement, though in what direction there is disagreement. Two men handcuffed together are chased by the police. They work in sync when it’s essential to do so (running), yet would happily forego the other for his own benefit. One prisoner decides they should both take a sleeping drug, and the first to fall asleep will have their hand cut off to bypass the cuffs. It’s a horrifying scene because it’s rigged. Only one man takes the drug, leaving the other in control. It says that movement can be manipulated to work against a competing party. It reminds a reader that this is what people do.

But Tatsumi cycles this story around to an idealistic outcome. The younger prisoner is freed of his murder charges because his cuff-mate knows who’s truly responsible, and the book literally ends with the young man walking off into the world in unison with a woman he admires. It’s a tidy ending, but it’s a play on what else the premise of handcuffed prisoners can provide, given they can settle on where to run to.

It’s also part of Black Blizzard’s overall performance. The book aims to run a reader through an ebb and flow of tight plot beats that all depend on the decisions of the characters. It’s a streamlined, efficient piece of work that showcases the different hues a cartoonist can hit. Alec Berry