On March 28, 1968, four years after its creator’s death, the first official non-Ian Fleming James Bond novel was published by Jonathan Cape. Although Colonel Sun appeared emblazoned with the pen name of Robert Markham it was no secret that this was Bond-aficionado Kingsley Amis: Markham was intended as an umbrella pseudonym under which different writers would continue the series, but much like George Lazenby in the following year’s film of ‘On Her Majesty’s Secret Service’, this was to be his (and Amis’s) only outing with the Bond franchise. Ian Fleming Publications has released an e-book of Colonel Sun this month, which is good news for anyone wishing to read this excellent adventure, but physical copies have remained mysteriously out-of-print since 1991’s Hodder edition. Puzzling, as this is one of the best James Bond books – I’ve even heard it said ‘the best’ – and a worthy addition to the canon.

Kingsley Amis was well qualified to pick up where Ian Fleming left off, having been a fan ever since discovering Casino Royale ‘on a railway bookstall’. In 1965, Amis published both the literary critique The James Bond Dossier and tongue-in-cheek The Book Of Bond (Or Every Man His Own 007), a how-to manual credited to Lt.-Col. William (‘Bill’) Tanner, who is of course M’s Chief Of Staff. How much of Fleming’s last novel, The Man With The Golden Gun, was entirely the author’s own work is often called into question, the book still being in draft form when he died. Kingsley was paid to recommend changes to the manuscript although none of his suggestions ended up being used. Upon its release, Amis reviewed the book as “lifeless” and wrote in the Dossier that it had “no decent villain, no decent conspiracy, no branded goods…and even no sex, sadism or snobbery”. In September 1965, Kingsley was offered the opportunity to work these components into his own Bond story – “an honour to have been selected to follow in the footsteps of Ian Fleming…a great popular writer” he wrote in the essay, ‘A New James Bond’ (collected in What Became Of Jane Austen?) – and that month set off for a holiday in Greece in order to scout locations. Shortly afterwards, in 1966, official Bond publisher Glidrose Productions Ltd. commissioned novelist Geoffrey Jenkins to also write a Bond novel. Set in South Africa, the story was based on an idea that Fleming had discussed with his friend Jenkins, but the resulting Per Fine Ounce was rejected in the end. (Two pages of the believed lost manuscript may be read here.) And so, Colonel Sun became the first James Bond adventure after Fleming’s passing, and the last one until John Gardner resumed the series thirteen years later in 1981.

It’s all very well to write about the world’s most popular secret agent, but could Kingsley Amis actually write James Bond? Anne Fleming, Ian’s widow, not only didn’t think so but was appalled by the very notion: “Amis will slip Lucky Jim into Bond’s clothing, we shall have a petit-bourgeois red-brick Bond, he will resent the authority of M., then the discipline of the Secret Service, and end as Philby Bond selling his country to SPECTRE” she wrote in a review of Colonel Sun requested by The Sunday Telegraph. The paper then opted not to run the piece for fear of libel. With her use of the simple future tense, it seems doubtful she had even read the book before penning this – and anyways, Amis did no such things; he captures the very essence of Bond, keeping with the character, substance, and scenery of Fleming’s stories. Amis himself admits in ‘A New James Bond’ – “It had been clear to me all along that I was not by nature or experience the ideal person to take Bond inside the gambling casino, aboard the hydrofoil yacht, down the advanced (in fact down any) ski-run or into many parts of the world Fleming had constructed for him.” But these are not the only components that constitute James Bond’s world and Kingsley gives us more than enough from 007’s previous life for us to accept and be swept along with his story.

The book opens on Sunningdale New Course, golf being a nod towards Goldfinger, though according to Kingsley, “a game I hope fervently to go to my grave without once having had to play.” We’d never know it by the account of the match and grounds, filled in by a friend of Amis’s who took him to the course. The Coventry Street lunch of ‘Whitstable oysters, coldside of beef and potato salad, and well-chilled bottle of Anjou rosé’ is painted from Fleming’s own culinary palate. And also on that first page we’re reminded of ‘Scaramanga’s Derringer slug’ that had ‘torn through (Bond’s) abdomen’ in The Man With The Golden Gun. But most recognisable is the pervading feeling of ‘the soft life’, that sense of complacency and boredom we’ve encountered at the beginnings of other books (Dr. No, From Russia With Love, Thunderball, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service) that haunts Bond whenever he finds himself away from the action, settling into dull routine work. Things quickly pick up however, as they always do, when Bond stumbles into a colossal kidnapping operation. He narrowly manages to escape but is unable to prevent the thugs from making off with M: such an act as abducting the head of the Secret Service is unheard of in peacetime and, as these terrorists are obviously after him too, Bond has little choice but to follow the clumsy, but cleverly written, lure to Athens. Once there he must simply wait for the rest of their plan to unfold.

Enter the heroine, Ariadne Alexandrou. Despite what the films have led us to believe, with ‘Roger Moore’ being as much a mandate as a star name, Amis has pointed out that on average Bond seduces ‘one girl per trip’, and that this is hardly excessive. Perhaps he was trying to prove this point (though one wonders where more could be fit in this tightly-timed exploit), but there is surprisingly little sex in Colonel Sun, especially considering Kingsley’s reputation (Martin Amis wrote in Experience – “A promiscuous man, and a promiscuous man in the days when it took a lot of energy to be a promiscuous man, Kingsley was excited by his contiguousness to yet more promiscuity.”) Alexandrou is a strong, independent woman, courageous and intuitive like the female leads Fleming wrote. In Greek mythology, Ariadne helped King Theseus kill the Minotaur, and Amis uses more of her legend both in the plot and to demonstrate Alexandrou’s tenacity. As with the Bond of the books, Ariadne is tough but also human: she falls for James but doesn’t let this compromise her sense of duty to the Soviet Union. Her principles are mocked and criticized from all sides but she behaves bravely and intelligently in the name of her cause. In the amusingly titled ‘General Incompetence’ chapter, an arrogant high-ranking official of the KGB dismisses her Communism as ‘romantic’ and ‘sentimental’ – a mistake that nearly proves disastrous for Russia.

But the Soviet Union is not the enemy here, or at least not the one Bond is fighting. Bond and Ariadne, British agent and Greek Communist employed by the Russian GRU, must work together to prevent a disaster that would severely damage both their countries. By the time of the later novels, Fleming switched the focus from the U.S.S.R. and SMERSH to the terrorist organization of SPECTRE. Already in the late 60s tensions between East and West were beginning to thaw. The films of the 70s accounted for this by featuring lone villains intent on world domination, and when Pierce Brosnan took over the role in 1995, after the Cold War had ended, the question of the opposition was once again an issue; the threat was no longer Communism but ideological terrorism. Ahead of this curve, Amis considered “Russia versus Britain too old-hat” and that “Red China as villain is both new to Bond and obvious in the right kind of way. And Chinese master-villain would be fun…” His Colonel Sun Liang-tan of the Special Activities Committee, People’s Liberation Army, is an Anglophile with a madman’s sense of destiny. Fond of British culture, Sun speaks English with a bizarre mixture of regional pronunciations, treating his captives, M and later Bond, with the utmost civility. This is, of course, all a prelude to the monstrous torture scene that surpasses even that of Casino Royale, and this simply a preliminary exercise before 007 is to take up his role in Sun’s grand terrorist scheme.

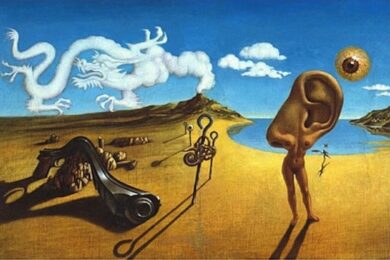

Acting on his own authority, Sun is intent on bringing about a spiritual union between himself and Bond. He waxes philosophical, quoting de Sade, as the prolonged anguish takes its toll on both punisher and punished. But Sun is not the only villain. Amis ties the new threat of Red China to an older one with the character of ex-Nazi officer Von Richter. Like Hugo Drax who had ‘half his face blown away’ and Blofeld’s changing guises, this ‘Butcher of Kapoudzona’, with the left side of his head burned and his disfigured ear, keeps to the trend of Bond villains having distinguishing physical characteristics. The combination of Sun and Von Richter is one of Amis’s many subtle callbacks to the Fleming books: Dr. No, his own ‘Dali-esque’ features causing him to resemble ‘a giant venomous worm’, was also half-Chinese, half-German.

The denouement is every bit as thrilling as one would hope. Bond, exhausted and damaged, manages to regain command, relying, as he has throughout the book, on his wits and muscle to save the day. Much as in new film ‘Skyfall’, there is a conscious move away from gadgetry, and Kingsley’s experience in the Second Army Signals during World War II was enough to provide a knowledge of weapons that could be used. Besides the violence, the climax is also highly fraught with emotion for all parties involved – and by this point there are quite a few. (In addition to the main cast there are henchmen, Albanian courtesans, Doctor Lohmann, and various members of the KGB. Not to mention Litsas, who despite being adamantly against Ariadne’s ideology, conveys Bond and Alexandrou to the isle of ‘the event’, having a personal interest in the proceedings.) The suspense of just exactly how the terrorists will accomplish their objective weighs heavily throughout the novel, the means interestingly (though ineffectively) prefigured in a dream while Bond is wracking his brain over this very question. In the Dossier, offering a critique as to how Fleming could have made his books more literary (should he have chosen to do so, Fleming often stated this wasn’t his business), Amis asks “What about a few dreams? – known as the handy off-the-peg method of injecting significance into any form of fiction.” Other literary points catch one’s eye too. As a man who knocked out three books dedicated solely to drinking (On Drink, Every Day Drinking, and How’s Your Glass?) Kingsley writes with authority on the local Greek liquors. And notorious for being fussy about such things to the point of penning The King’s English, Amis pays special attention to language and pronunciation: Anthony Burgess, who himself wrote an early draft of ‘The Spy Who Loved Me’ screenplay and the introduction to the 1988 Coronet paperback editions of Fleming’s novels, often praised that aspect of Amis’ work. (It is interesting to note in this year of a new Bond film and Damon Albarn’s Dr. Dee opera plus album, as pointed out by Burgess in said preface, 007 was also John Dee’s number when he worked for Queen Elizabeth I’s intelligence services.)

‘The Spy Who Loved Me’ film would also see Bond working with a female Soviet agent. The script for that movie was written from scratch, Fleming having specified that nothing from the original novel be used, the story being too dear to him. Location-wise, Greece is seen in ‘For Your Eyes Only’, but the most obvious lifts from Amis’ novel come in ‘The World Is Not Enough’ with M’s kidnap and the ‘Die Another Day’ character Colonel Tan-Sun Moon. Indeed when we first encounter the Colonel of the book it is in the chapter ‘Sun At Night’. Although Kingsley found the films ‘denatured’ and ‘an almost separate being’, he still held out hope for a cinematic release of Colonel Sun. Rumour has it that despite owning the rights, ‘Cubby’ Broccoli was put off making a film version of Sun by Kingsley’s public dislike of the Roger Moore movies. Earlier, when Harry Saltzman was still involved with EON Productions, he had “blackballed” the notion of a Colonel Sun film in response to Glidrose rejecting Per Fine Ounce, a project with which he was involved.

This last bit of information was gleaned from James Page & James Wheatley’s informative introduction to the Colonel Sun comic, published by Titan Books. A newspaper strip, written by Jim Lawrence and drawn by Yaroslav Horak, ran in the Daily Express from 1969-1970. The stand-alone Titan edition features this piece on the novel, an interview with Lawrence, an article on Amis, and an Introduction by Bond Girl Britt Ekland. Colonel Sun is also collected in Titan’s James Bond Omnibus 003 . And these are the only places you’ll find the story in print.

Faithful and enjoyable as the comic is, it is still not Amis’s original novel, the prose being a large part of why we read Bond in the first place. The books may not be entirely literary but with their romantic sense of adventure, enticing descriptions of both the exotic and the everyday, and believable mental and physical struggles, they keep us, as Fleming did say was his business, ‘turning the page’. With John Gardner’s 007 novels (of which Kingsley did not think much, calling For Special Services ‘an unrelieved disaster’) seeing a reprinting this year, it is a shame that Colonel Sun remains in the dark. It is not only one of the best Bond books, but one of Amis’s finest novels as well.