Where would John Lennon be today had he somehow dodged Mark Chapman’s bullet back in December 1980? It’s one of those deliciously futile questions. A perennial poser for every popcult PKD with a pet hypothesis. I can’t speak for what kind of execrable music he might’ve released over the last thirty-seven years. Nor dare I guess what horrifying shape his aging maw might latterly have assumed or how he might have spent his millions. But after reading Carl Cederström’s The Happiness Fantasy, I am more or less convinced that, given the opportunity, he would have voted for Trump.

This may seem absurd – the bedridden and bespectacled icon of peace, love and understanding throwing in his lot for a president whose diplomatic abilities extend to screaming “fuck you” or “you’re fired” at whoever Fox News has deemed the enemy that week. But the unlikely duo have more in common than you might think. As Cederström points out, they share a paradoxical kind of idle productivity. After all, who but Trump would think he could end wars without getting out of bed – except, of course, for John Lennon. They are also alike insofar as being widely perceived as “authentic” – Trump sets, as Cederström puts it, “his own path without paying too much attention to what others say or think.” They are also both relentless and unashamed in their hedonism. They are – or were – both pleasure seekers.

But the pleasure each man sought, with all its excesses, would have been unrecognisable to Epicurus, the Greek philosopher for whom pleasure was the highest good. For Carl Cederström, the peculiarly modern “happiness fantasy”, embodied in the “dreamlike” Lennon and the “nightmare” of Trump, entails a particular moralistic injunction to reach “your full potential as a human being … to live in a spirit of authenticity … to pursue happiness in the form of pleasure … [and] to submit yourself to the market, working hard to develop your brand and gain a competitive edge.”

This is the story about how a certain idea of what it means to be happy, first developed by an eccentric Austrian psychoanalyst, was later taken up and transformed by intentional communities in the Californian desert, motivational speakers, and management theorists, until an idea once considered so subversive that its originator was thrown out of psychoanalytic associations all over Europe and finally made a scandal of in post-war America, would ultimately become a fully integrated, almost essential element of modern capitalist ideology.

And if that already sounds a little bit Adam Curtis, you won’t be surprised to find a reference to the British documentary maker’s Century of the Self in the very first paragraph of the first chapter. But while Curtis’s schtick has grown weary, his wild leaps from the hyperspecific to the paradigm-defining general feel tired; Cederström’s style feels unforced, his examples often eerily prefigurative. The libidinal politics and pleasure-enhancing "orgone accumulators" of Wilhelm Reich. The confessional ‘hot seats’ of Fritz Perls at Esalen. The compulsory narcissism of Werner Erhard’s est seminars. The productisation of happiness itself at Zappos and other twenty-first century corporations. The strange journey of LSD from Haight-Ashbury to microdosing Silicon Valley creatives. In each case, Cederström’s prose cooly observes the slow institutionalisation of something once considered subversive: the idea that our sense of self might derive not from church or state, not from job or union or family or class or culture, but from our own individual drive for pleasure, reconceived as the key to your unique self, the USP of Brand Me.

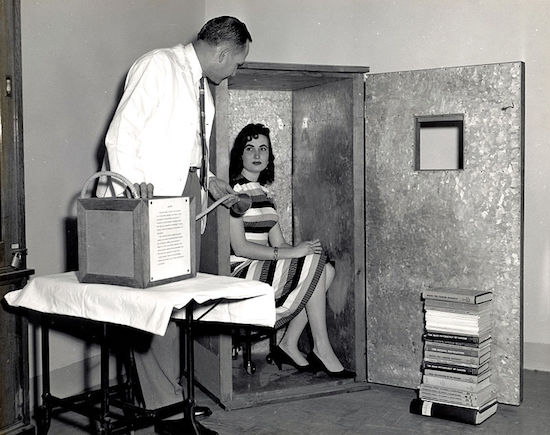

An orgone accumulator

Writing this book in the autumn of last year, at the height of the #MeToo movement, it is not perhaps unsurprising that Cederström came to recognise the syndrome he was diagnosing as a peculiarly male fantasy, a fantasy which madewomen, ever since it was first popularised int eh 1960s, more often its objects than its subjects. And in the fall of Harvey Weinstein, the growing ignominy of the grab-em-by-the-pussy presidency, Cederström perceives its death throes – or at least, a burgeoning realisation that such a of thinking and being in the world is no longer acceptable, no longer really cool.

The Happiness Fantasy had already gone to press by the time twenty-five year-old Seneca college student Alek Minassian allegedly drove his van onto the west-side sidewalk of Yonge Street in Toronto shortly after posting on Facebook that “the Incel Rebellion has already begun”. But had he still been tweaking his manuscript earlier this spring, Cederström would doubtless have seen in the subreddits and other darkened corners of the online manosphere where so-called ‘involuntary celibates’ key each other up towards violence, some hint of what happens to those both interpolated and excluded by the happiness fantasy he diagnoses. This does not diminish the persuasive power of his closing prescriptions.

We need to “stop thinking of happiness as a personal pursuit,” he declares. “Instead of a happiness fantasy based on the notion that we should win ourselves and become authentic, we could perhaps imagine a happiness fantasy in which we lose ourselves and become inauthentic. We would lose ourselves in the sense of acknowledging our fundamental dependency on others, including people we will never get to meet or know.”

Cederström is too smart to believe we can do away with fantasy altogether – nor would he want us to if we could. What he asks for instead is a different, more inclusive kind of fantasy – a “feminist happiness fantasy”, as he puts it. “Guided by such a fantasy,” he concludes, “we would no longer be impressed by people – mainly men – who boast about their personal transformation and quest for authenticity. We would not reward those – mainly men – who selfishly pursue their own personal goals at the expense of others. We would no longer tolerate sexual violations – committed, almost exclusively, by men – in the name of a right to pleasure. And together – women and men – we would imagine new ways of living and working, which are not definied by market-values alone.”

The Happiness Fantasy by Carl Cederström is published by Polity