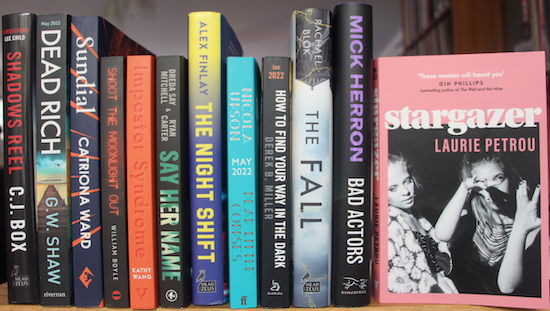

The first of these columns, published last year, kicked off with an appreciation of C.J. Box’s Joe Pickett series. Regular as clockwork, another instalment has arrived, and while Shadows Reel may not be the best of Box’s twenty-two books featuring the Wyoming game warden, it’s still a satisfying and pacy read. Many writers seem to struggle to keep long-running sagas fresh: it’s not just the improbabilities that attend ageing heroes called upon to get older gracefully while still packing crime-fighting punch, there’s also the limitations that come with taking the regular reader back to familiar environments while keeping narratives accessible for new readers and minimising the repetition of backstory. Box circumvents these by giving each book a secondary theme. This time out, there’s buried WW2 secrets and contemporary agents provocateurs to add prickly intrigue to a plot that, in such experienced hands, feels like it’s running on rails.

Also returning from the first Burden is William Shaw, though he arrives this time around sporting a new brand. Dead Rich marks a departure, with no central police characters and not being part of either of Shaw’s previous (and outstandingly good) series. The mysterious science of crime-fiction marketing means, therefore, that it makes sense for it to hit bookshops under the name G.W. Shaw. Devotees of the wonderful DI Cupidi books, set on Kent’s southern coast, need not worry, though: following last year’s brilliant The Trawlerman, it’s still recognisably the same considered, meticulous and careful hand at the tiller. We are at sea again in this uncannily prescient story of mysterious misadventures of the ultra-high-net-worth bracket, most of which takes place on board a Russian oligarch’s yacht. Dead Rich proves what repeat customers for Shaw’s books have known for several years now: this is an author who can evidently do pretty much anything he puts his mind to. In an afterword to last year’s book he mentioned how the first chapter had been written during a writers’ workshop: here he delivers another masterclass.

Nicola Upson has been writing a (fictional) series which features the (real-life) golden-age crime writer Josephine Tey for more than a decade and a half, and Dear Little Corpses is the tenth to appear. The period setting is brilliantly brought to life by Upson’s careful yet lightly worn research – sections set in and around the Wilkin & Sons jam factory in Tiptree are particularly vivid – yet what strikes home most forcefully in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is its story of refugee children being billeted in the English countryside. Upson would have written her book months before, but the scenes of well-meaning locals aiming to offer a welcome but not really knowing how, and dislocated and frightened children struggling to adjust to enforced exile, will inevitably mean something rather different, and perhaps far more powerful, now.

Among the authors also appearing uncannily prescient given their moment of (UK) publication is Kathy Wang. At first with Imposter Syndrome you think you’re in for a satire of Silicon Valley and Sand Hill Road, which would be fine enough anyway – but, while Wang may not be as spleen-rupturingly angry as Jarett Kobek, she’s still a writer capable of getting her teeth into her subject’s most vulnerable parts and leaving it bloodied and bruised. The book proceeds carefully and methodically, as if she’d drawn up a checklist of start-up ills she needed to address and was working her way through it. Through Alice, Wang’s Chinese-American protagonist, we are read the roll call of the casual racism, sexism and ageism of the tech-bro world; but in the shape of Julia Lerner, the head of the deliberately (and deliciously) nebulous corporation Tangerine, Wang goes deeper. Feted by the media, cosied up to by politicians, lionised in public yet loathed behind her back by her contemporaries, Lerner has a secret life, and Wang users the character to skewer the whole tech-utopian ecosystem, including – cleverly, subtly and quite brilliantly – its pretentious and self-serving veneer of supposed wokefulness and artificial gloss of inclusivity. This is a timely, provocative and very necessary book which has an agenda yet never forgets to be entertaining, relatable and riveting.

Another book that uses the form and feel of crime and thriller genre writing to make a number of potent, important points about far wider societal issues is Say Her Name. Dreda Say Mitchell and Ryan Carter make their story work on a series of different levels simultaneously, as a biracial woman’s curiosity about her birth parents leads to the uncovering of abuse, violence and deceit. But at its heart this is a novel about erasure, its consequences, and the paramount importance of righting its wrongs and standing up to its pernicious evils. At its heart – like a number of the books included here – it is at its most compelling and emotionally resonant when operating in the traditions of the family saga. Mitchell and Carter’s writing is often spare and occasionally brittle, but during the passages where Eva is remembering her late stepmother or talking with her complicated and conflicted stepfather, Sugar, the effect is almost alchemical.

Catriona Ward gave herself something of a problem after last year’s astonishing The Last House On Needless Street. How could anyone follow a book so captivatingly, creatively different? The answer seems to have come in two parts: first, don’t try too hard; and second, stick to the realm of the familiar yet disturbingly strange that gave Last House its compulsive, hypnotic pulse. Rather like Shaw’s new book, Sundial puts the reader in what feels like familiar authorial hands, but plunges us into a completely different kind of time, place and atmosphere. What Ward does superbly, indelibly, is create a world you get caught up in, situate it in a small slice of a believable reality (this time a compound in the middle of the desert, where Last House was at the end of a road deep in a forest), then pepper the landscape with damaged people hiding terrible secrets. Though this may feel in some ways a more conventional, less experimental kind of a novel – and while those crime-fiction fans who prefer to stay within the guardrails of procedure, investigation and linear narrative may find it a challenge – this is a book that makes as forceful an impression.

The past comes back to haunt the protagonists in William Boyle’s Shoot The Moonlight Out, too, though this is a book that will feel more familiar in approach and tonality than Ward’s mirage-cum-nightmare. Boyle sets the action either side of the turn of the millennium, in a Brooklyn that you can almost taste and smell from his classy and understated descriptions. He’s just as strong with character, individuals and their motivations conjured convincingly from asides and reactions. If there is a criticism to be made it’s that the book is perhaps over-reliant on coincidence. But those who are willing to see myth and fable as rooted in everyday reality won’t find a thing to dislike in this immersive and absorbing hard-boiled tragedy. Alex Finlay’s often dazzling The Night Shift is cut from similar US-based time-shift-narrative cloth, but has to come with a similar, if minor, caveat: after creating a world that feels vibrant and alive and entirely believable, some of the elaborate hoops Finlay has his characters jump through in order to arrive at a fully resolved conclusion can come close to reminding the reader that this is fiction, not reality. But if that isn’t the kind of thing that normally puts you off, then this will surely be one of the best half-dozen thrillers you’ll pick up all year.

Given the website this column is written for, and also given one of the key musical predilections not just of the venerable Mr Doran but your columnist too, the idea that we’re reviewing something called The Fall is probably going to have some subscribers wondering about whether we’re not just trolling them. But fear not. If Rachael Blok is familiar with the work of the late Mark E. Smith and his ever-changing retinue of musical mavericks, there is no sign immediately visible in her work. (Not that it would have been a bad thing, but… Anyway.) If you were to outline the key ingredients of the story, it might appear as though Blok has half an eye on getting her book (the fourth in a well-regarded series) picked up for a TV adaptation: there’s a diffident European detective, a wedding being planned in a picturesque English cathedral (the real-life St Albans) where the verger finds a dead body – apparently fallen from the roof – just before an exhibition opens, examining the occluded history of a local asylum. Blok clearly relishes the challenge of setting up a complicated enough puzzle to satisfy fans of whodunnits, but her real focus is on the prose itself. As with Mitchell and Carter, Blok is interested in those whose stories were struck from the record, or never allowed to be inscribed upon it to start with, and her writing is sufficiently sharp to get under your skin before you realise she’s made the first cut.

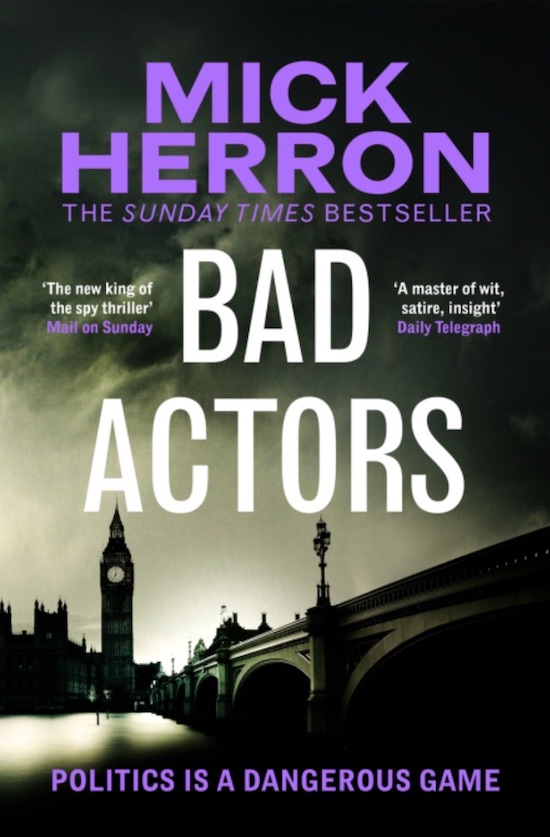

Mick Herron’s is another name that has made an appearance here before, and we make no apologies for that. The Oxford-based author is among the finest exponents of the thriller-writer’s art around at the moment, his ascension to household-name status surely a formality had his Jackson Lamb series been optioned by a broadcaster with a bigger reach than Apple TV. In a genial afterword here, Herron makes a kind of apology to Gary Oldman, Kristin Scott Thomas and the others who star in Slow Horses (Apple’s adaptation of the first of these books), pointing out that his decision to give Bad Actors its title had long been foreshadowed in earlier work. But you get the sense that he might well have chosen to call it that on the day the show was green-lit anyway.

This is nominally the eighth in the series (though there are two earlier books, the brilliant Reconstruction and Nobody Walks, which are set in the same milieu and can be considered prequels) about the disgraced spies exiled to the pen-pushing purgatory of Slough House, and it follows a template regular readers will be delighted to find largely unchanged. There is political satire, pointed polemic, tightly-woven and expertly-crafted plotting, and an out-loud laugh every five pages. But perhaps Herron’s greatest gift is his unerring ability to paint an unmistakable, singular, recognisably (if discomfitingly) accurate portrait of a grey, cold, post-Brexit Britain, where its dishevelled institutions try to shore themselves up by gazing at their corporate navels while the outcasts and the marginalised are left to cobble together a solution to save the day from the forces of evil. As with all the books reviewed here that are parts of series, this one can be read as a standalone, but to get the most out of it – and just because they’re all so excellent and enjoyable anyway – our advice to a newcomer would be to start at the beginning and devour them all. You’re in for a treat.

The final two books this time around share some similarities. Both are only tangentially crime fiction, both work as large-canvas overviews of families across lengthy time periods, and both are uncommonly, arrestingly excellent.

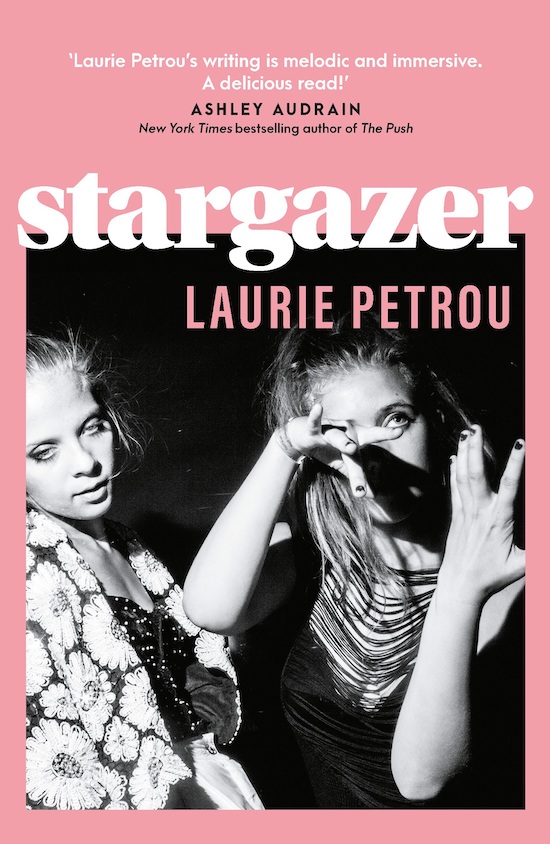

Laurie Petrou does something that feels as if it goes beyond writing in Stargazer, a book that looks at two young women for a protracted and pivotal time in their lives, and finds a way to examine everything in the round. This isn’t a depiction of characters or a recreation of a historical moment (though it is both those things, too); it’s like a sculpture in word form. Petrou steps around her subjects, viewing them from 360 degrees and through multiple timeframes at once, presenting the results in a way that feels and reads like a novel but that conforms to few of the rules it might ordinarily be expected to obey. Throughout, she subverts expectations – about class, privilege, creativity, family, friendship and everything else – and succeeds both in involving the reader and forcing you to confront and reassess your preconceptions. Crime fans who prefer their entertainments to follow a more traditional format may struggle to get into the groove. Although it’s powerfully foreshadowed, there is no specific crime, as such, until quite late in the piece. But for this reader, that just made it even stronger.

In How To Find Your Way In The Dark, Derek B. Miller goes back to the teenage life of Sheldon Horowitz, the octogenarian character at the heart of his 2012 masterpiece Norwegian By Night. This prequel has attracted comparisons – not least from Miller himself – with Michael Chabon, but John Irving is another reference point that feels entirely valid. This is a big, baggy, widescreen epic, telling a long story through small but detailed vignettes stretching over a decade and with resonances that are pan-generational. Where Petrou situates her narrative in a music-bedecked Canada of the 1990s, Miller’s characters live out their lives amid the virulent if often knee-jerk anti-Semitism of late 1930s and early 1940s north-eastern USA as Sheldon foments vengeance against those who killed his father while he and his best friend, Lenny, navigate their teens in a world going wrong. Miller is an author of vast talent, whose writing fair sings off the page. Petrou’s phrasing is incisive and original, her ability to capture the essence of a moment and transmit it with apparent effortlessness both rare and enviable. Both these books are remarkable, rewarding and very highly recommended.