Wagnalls Wheel, 2010, Brian Dettmer

2013: The Year of the List, as it appears on the traditional Chinese Zodiac Calendar. From cats (yes, even cats, which untill this year had barely appeared on the World Wide Web) to mental health issues – nothing was safe from listification. And, with BuzzFeed‘s continued domination of the internet, it’s easy to forget that books – perhaps also containing lists! – were published at all.

But they were – and what better way to celebrate than with a list of highlights from Quietus contributors, editors and friends?

Forever contrary and always malcontented with traditional forms, however, this seemed a good opportunity to use that crystal ball we got for Christmas (which hitherto had remained boxed, with receipt firmly attached via a named-brand tape) and pick out some forthcoming gems, too. (I guess it’s safe to say Natasha Beddingfield never worked in publishing before becoming the voice of her generation – the rest, at least as far as this year goes, was probably written a year-or-so ago.)

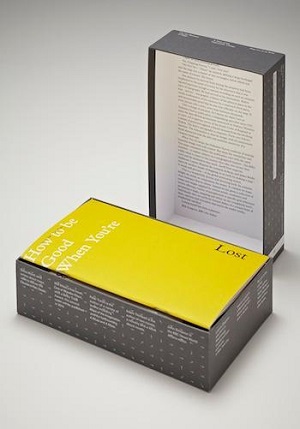

Where You Are – Various Authors

(Visual Editions)

It’s borderline-impossible to properly categorise this book for several reasons, but the two of which that come most quickly to mind are the sheer breadth of the project, in the sense that it covers more or less every conceivable category imaginable (except Baby Yoga, though it’s entirely possible I missed that one), and that – well – it isn’t technically ‘a book’. It’s actually several books ("pamphlets" for the sake of pendantry). Several books by several authors and artists. Several books by several authors and artists, both individually and in collaboration. Several books by several authors and artists, both individually and in collaboration in a box. A Really nice box.

The spectrum of contributors that this seemingly forever-innovative publisher (see: Jonathan Safran Foer’s Tree of Codes, Adam Thirlwell’s Kapow! and Marc Saporta’s Composition No. 1) offers up here is mind-boggling: of-the-moment contemporary authors, Tao Lin and Sheila Heti, nestle neatly next to artist Olafur Eliasson (of The Weather Project fame) and philosophy talking head Alain de Botton in such a way that, really, you can see where Pandora was coming from. (Again, it’s a really nice box.)

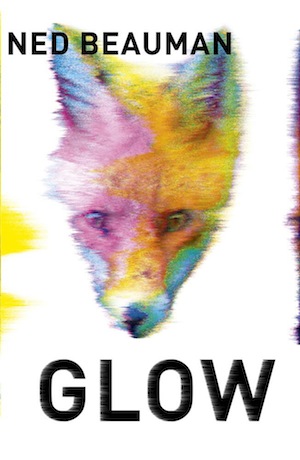

Glow – Ned Beauman

(Sceptre, May 2014)

If Ned Beauman had won the Booker Prize in 2012 for his longlisted second novel The Teleportation Accident he’d have inched Eleanor Catton’s record by a year. Instead, he was – if you’ll forgive the image – beaten off by Hilary Mantel. Regardless, between that and his debut, Boxer, Beetle, Beauman’s prose – simultaneously dark, intelligent and some of the out-and-out funniest I’ve had the pleasure of reading in a long time – have established him as one of the most exciting voices in contemporary fiction. I’ve been sleeping with that psychedelic fox for a little while now – he’s a randy little bugger, but it’s bloody brilliant.

– Karl Smith, Literary Editor, The Quietus.

The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Modern Myths – John Gray

(Allen Lane)

We’re all fucked. Pretend to be a kestrel.

– John Doran, Editor, The Quietus.

Derek Jarman’s Sketchbooks – Stephen Farthing & Ed Webb-Ingall

(Thames & Hudson)

A tantalising glimpse of the meticulous sketchbooks made by Derek Jarman to accompany each of his wonderful projects came in the 2008 film biography Derek, where they were revealed being taken out of cardboard boxes deep in the bowels of the BFI archive. Thankfully no longer in the dark, Jarman’s sketchbooks have been scanned, annotated and beautifully presented here with context, commentary and tribute in text by friends, collaborators and critics, including Tilda Swinton, Jon Savage, Toyah Wilcox and Neil Tennant. Jarman’s sketchbooks were labours of love – he bought the foot square photo books blank in Italy, and worked individualising the leather covers before he filled them with images, sketches for sets, invoices and the ephemera of filmmaking. But on top of that there’s 1991 letter from the Met Police informing Jarman he won’t be prosecuted for participating in an Outrage protest, or ‘admitting’ that he had had gay sex when it was illegal, or the £10 note that was his fee for War Requiem. More than just production notes to Jarman’s films, these Sketchbooks capture the creative and personal life of one of the late 20th century’s finest artists.

– Luke Turner, Editor, The Quietus.

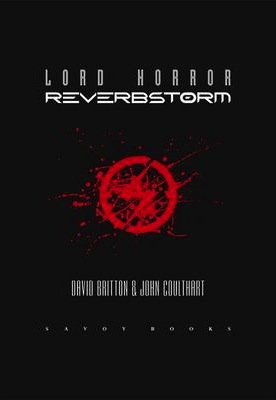

Lord Horror: Reverbstorm – Script: David Britton, Art: John Coulthart

(Savoy Books)

Reverbstorm is not just a comic book, it’s not even a (yuck) ‘graphic novel’, instead it’s better looked upon as a portal to a frighteningly vivid alternate history, or should that be histories? Most obviously its subject matter is the holocaust, but there’s no hand wringing here; no girls in red coats or boys in striped pyjamas. Through the eyes of Britton’s perennial court jester, Lord Horror, we see the holocaust as both farce and cosmic tragedy, the hideous culmination of whole histories and cultures of persecution. Seemingly everyone and everything is implicated from pointilism to rhythm and blues, James Joyce to Tarzan. Reverbstorm’s detonation of linear narrative structure forces the reader to see the whole messy flail of the 20th century and to ask serious questions of our assumed innocence in both the crimes of the past and the ones lurking around the corner.

John Coulthart’s solid black lines and grotesque architectures make crystal clear the links between modernist monstrosity and the might-is-right geographies of the death camps. His characters, no matter how grotesque, are merely shadow puppets against the ever changing metropolis that engulfs them; champagne corks bobbing in the time streams. His style is totally unique and suggests another alternative history: what might have happened had comic book art side-stepped the bubble gum pop of Kirby and the superhero school and instead leapt straight from Burne Hogarth to Moebius, taking in as much Beardsley and Harry Clarke as possible? The result is finally available for all to see. You will never breathe in stranger, more intoxicating scent than Reverbstorm.

– Mat Colegate, Film Editor, The Quietus.

Tampa – Alissa Nutting

(Faber & Faber)

"I spent the night before my first day of teaching in an excited loop of hushed masturbation, on my side of the mattress never falling asleep."

So begins Alissa Nutting’s first full-length novel Tampa; the story of female-Humbert Celeste Price and her relentless pursuit of one of the pubescent teenage boys she teaches. Not to be mistaken for a simple inversion of Nabokov’s Lolita, (the parallels begin and end with their mutual unsavoury taste in adolescents) Nutting’s hyperbolic take on the fetishisation of the female predator opens up a valid discussion about contemporary treatment of women in the media, as well as providing a brilliantly written insight into the troubled mind of one of the most intriguing and complex narrators of 2013.

Sophie Coletta, Reviews Assistant, The Quietus.

Man V. Nature – Diane Cook

(Harper, 2014)

[There’s no cover image for this book yet, so – in the spirit of the list – here’s a cat.]

I’m most looking forward to Man V. Nature, the debut collection of Short Stories by Diane Cook, coming out this year. She creates satirical parallel civilisations to ours, their cultures and characters both surreal and unrecognisable to us but close to home: full of strange routines and superstitions, violence and difficult humour. You can read one of her stories at Guernica Mag.

– Rachael Allen, Online Editor, Granta.

Eat My Heart Out – Zoe Pilger

(Serpent’s Tail, Jan 30th)

You wait around for ages for a properly funny novel about being young and in London nowabouts, and in 2014, happily, two total beauties are about to come along at once. I just finished Zoe Pilger’s debut Eat My Heart Out, which I got a massive kick out of from start to finish. It’s about a London a lot of us will recognize (poverty, drugs, casual sex, poshos, squat raves, aimlessness, self-mutilation-on-the-bus) and it’s narrated by a sassy and hilarious and completely charming young maniac called Ann-Marie. It’s a glorious hoot from start to finish: I really wish there were

more novels like this these days.

My Biggest Lie – Luke Brown

(Canongate, April 3rd)

I’m also currently halfway through my pal Luke Brown’s debut: another zinging and thoroughly LOL-inducing tramp around the London we know and love. Luke was an editor for some years and a lot of his book takes place in the well-fucking-zany world of London publishing; all shitfaced Notting Hill lunches, vast quantities of cocaine and yet more hopeless poshos. It’s got heartbreak, grown-up wisdom, gleefully vicious satire and a dreamy chunk of action that takes place in Buenos Aires, and although I’m only seventy pages into it as I type this, frankly I love the shit out of it already.

– Stuart Hammond, Books Editor, Dazed & Confused.

Black Neon – Tony O’Neill

(Parisian 13e Note Editions)

Tony O’Neill’s latest novel, Black Neon made its debut in Germany and Italy in 2013, and is out in France this month with the Parisian 13e Note Editions. It has yet to come out in English, but there are rumours of imminent developments in that area, which would certainly be a relief given an impatience with my own broken French. Nevertheless, I look forward to attempting to read the French edition, given an "excellent" French translation, according to O’Neill, by Étienne Menanteau, and the idea of reading LA sleaze in the language of Gainsbourg, Rimbaud and Sartre. The story itself is a sequel to brilliant Sick City (2011) – though according to the French publishers, "On peut lire l’un sans avoir lu l’autre". It inhabits and embodies the underworld of LA excess, slipping sobrieties, enamoured criminality and the particular brand of neon noir that fans of O’Neill will be familiar with and likely craving already.

– Christiana Spens, Quietus Contributor; Director, 3:AM Press.

Red Doc> – Anne Carson

(Jonathan Cape)

Earlier this year, Carson fever hit the poetry world. Red Doc>, the follow up to her verse novel Autobiography of Red (which detailed the formative years and sexual awakening of a red devil named Geryon), was hugely anticipated. But Red Doc> isn’t a typical sequel.

All the characters are re-named and, as they navigate on a road trip through ice caves and psychiatric wards, the attention shifts from the red devil to his former lover, now a jittery war veteran, whilst a Greek tragedy inspired Chorus punctuates the story.

But then, Carson isn’t really a typical poet. She has a reputation for being an inventive and experimental writer. On the page, Red Doc> is dynamic – the form shifting from bookmarked’ justified poems to fragmentary snatches of dialogue. And the writing itself is excellent – the ending especially, as Geryon’s mother is in hospital, is some of the most arresting poetry I’ve read this year.

I love this complex and beautiful book about how our relationships with friends, family and lovers change, and I love Carson’s work. I wish the book, and Anne (first name terms) the best of luck in January’s T.S. Eliot Awards for Poetry. #teamcarson

– Alex MacDonald, Quietus-published poet, Editor, Selected Poems.

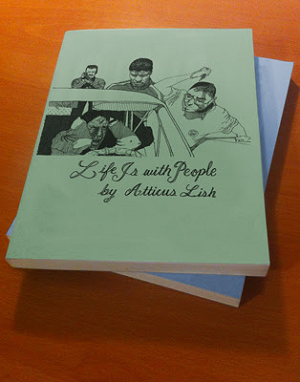

Life is with people – Atticus Lish

(Tyrant Books)

I remember the publisher of this book, Giancarlo DiTrapano, telling everyone that if they bought Life is with people and didn’t love it he would refund them in full and let them keep the book – no questions asked. It isn’t easy to publish a book that is as much an object of art as it is a text of it. It costs a lot of money to print books like this (every page of it lined like looseleaf, with the feel of a nice journal you got for Christmas years ago) and so you have to raise the price up a little, to ensure you break even on the relatively small print runs typical of indie presses. But when you raise the price of a book to $20 you risk alienating readers, and so it’s got to be good, you’ve got to stand by it 100%, and – if it fails – you at least know you didn’t compromise the work. You printed the book the way it should have been printed, and you put it out into the world, hoping someone appreciates that.

Opening Life is with people makes me feel like a concerned teacher sorting through the scribbled drawings of a troubled student’s binder: it’s a gritty, hyper-attuned coming-of-age through images of people. People happy like pigs in shit, filthy, in their element, and uninhibited. I assume Atticus Lish grew up in New York City, because he depicts the monstrous, snaggle-toothed, gimp-outfitted guy on the subway with nothing but love. And the starved-looking, lanky hairless guy in boots, nonchalantly shitting on the sidewalk, well, he’s with us too.

– Spencer Madsen, Editor and Publisher, Sorry House.

Black Cloud – Juliet Escoria

(Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2014)

This is a complete conflict of interest but I don’t care. The whole business of publishing is a conflict of interest and the history of literature typically is a history of friends and boyfriends and wives and children talking about one another. So here goes: The book I’m most looking forward to in 2014 is Juliet Escoria’s Black Cloud from Civil Coping Mechanism. It’s original title had something to do with drugs and boys and it’s a book about drugs and boys but it also contains some of the coldest and meanest prose I can think of right now. It’s a big throbbing sex organ of a book and it wants to punch you in the chest. It’s going to knock the wind out of a lot of people and make them think they’re dying, but then they’ll realize – no I just had the wind knocked out of me. And finally they’ll be able to breathe again and it’ll feel like the first real breath they’ve ever breathed.

Escoria is going to be our lungs in 2014.

– Scott McClanahan, author, Hill William (2013, Tyrant).

1996 – Sara Peters

(House of Anansi, 2013)

Sara Peters’ 1996 is the first poetry book since Chelsey Minnis’ Bad Bad that I’ve bought copies of to give to friends because it felt somehow of my own teen-noir heart:

‘My soul and I, we were sensitive

And our project was to process

Unrequited love—’

I bought it on the back of a recommendation from the poet Emily Berry and read it with the same urgent and devout terror as my older sister’s diary. In it the narrator and the babysitter are ‘playing lesbians’; she and her sister are ‘practising’ for ‘future rapes’; in bed she is ‘involved in the serious business of ripping apart’ her own body. I was scared at what I might come to understand (and fear) about myself and about others through reading it, but it felt strictly necessary, like poking a bruise to check the tenderness. Even though one poem opens: ‘From the beginning / You should know I am embellishing,’ nothing in this book is ornamental. Mainly, I envy every line.

– Amy Key, Quietus-published poet; Editor, Poems in Which.

No Medium – Craig Dworkin

(MIT Press)

The most remarkable thing about Craig Dworkin’s magnificent exploration of the art of the blank, the silent, the erased, is not the concise, erudite engagement with the material; nor the way the book interrogates the word "medium" itself, investigating how we interpret the term "media" today; but the geek-ish passion which suffuses every page making the book such a joy to read. After reading the first chapter, I bought two books cited in the footnotes.

No Medium has about it the tone of a carefully selected playlist: a selection of silences and spaces chosen by someone whose passion for their research is all-consuming. The book is no worse of for this and Dworkin’s prose enables him to articulate the notion that a "medium" cannot be read just in terms of its material existence, that there is a relational connection to shifting material conditions, perfectly succinctly with rare style and wit. This rich, exhilarating book transforms the blank curiosities of its focus into beautifully sharp exemplars about the complexity and depth of media theory.

If this weren’t enough, it also contains an exhaustive historical list of recordings of silence in the last chapter.

– Daniel Fraser, Quietus Contributor.

The Helens of Troy, New York – Bernadette Mayer

(New Directions)

A literal take on the (minorly altered) mythological character’s title, the poems in this pamphlet are based on Mayer’s interviews with women named Helen in the city of Troy, New York state. Collectively they make for a kind of free-form conceptualism, fixing themselves around the life stories, phrases and countenances of each Helen, with smart asides and oblique references to the overarching myth. Lines from the texts, which for me never feel outweighed by the concept, often appear as though they have been almost directly transcribed from the interviews, the most effective of these becoming a whimsical mantra throughout one of the poems: ‘i took off, it was fun, i loved it’.

I like that The Helens of Troy includes photographs, which seem to function as documentation or ‘hard evidence’ of the pre-composition interviews.

More generally, I like pamphlets a lot at the moment and am looking forward to forthcoming titles from Eggbox’s F.U.N.E.X imprint (following on from Matthew Welton’s Waffles, 2011) as I don’t think there are enough of these sorts of things being made in the UK. Clinic also have some exciting plans for the form in 2014.

Mostly I like that The Helens of Troy is not just an airtight text composed for purpose, but the material record of an extended process.

Sophie Collins, poet, Editor, tender journal.