One of the great joys of ten years of being a fan of British Sea Power has been the regular Newsboost emails sent to keep the wider world informed of the group’s activities. Penned by a figure called The Secretary and named for rocks, birds or perhaps lesser known figures from British musical history, Newsboots Ooolite, Horse Gowt, or Jonah Lewie, these snippets of information were glorious pieces of writing, far from the faux-matey or clearly label goon-penned missives that are usually the standard fare when it comes to rock & roll communications to those who have inadvertently signed up to their mailing lists. Now, in rock and family memoir Do It For Your Mum, The Secretary – music journalist and Quietus contributor Roy Wilkinson – is allowed more than the confines of an email communiqué to let his words breathe. You can read Luke Turner’s review of Do It For Your Mum at Caught By The River, and read an extract below. It’s 2003 British Sea Power are doing well in the UK and, as they travel to the skyscrapers and hyper-modern culture where Tiger tanks sit alongside plastic models of girls, Roy Wilkinson reflects on his father’s visit to the Orient in unhappier times.

On arrival we climbed into a Cedric Super Custom. It was an attractive machine, manufactured by Nissan and named after the young heir in Little Lord Fauntleroy. As the taxi followed curving flyovers there were posters advertising Electric Mole, Mongol 800 and Coaltar of the Deepers. All ventures in rock and pop. On the news stands sat the latest copies of Peach John, Happie Nuts and Men’s Joker.

In 2003 British Sea Power had released their debut album and become a professional touring rock band. If all this was meant to be taking us towards a sparkling new geometry, made entirely of fibre optics and ovation, Japan was a good place to end the year. In December a minibus driven by Colin from Breaks-A-Way of Shoreham-by-Sea had collected us from above the butcher’s shop in Portslade. We had seemingly started the day in monochrome, on a street apparently made from suet and slate. The flight transported us decades into the future. But it was a future informed by odd, glancing interpretations of the past. The nineteenth-century novel Little Lord Fauntleroy had resonated in Japan. The young Cedric was reliable and steadfast. Surely this would be a good name for a car?

We stood outside our hotel. The buildings were made from light – wide and high, an expanse of twinkling electric blues and neon reds. It felt both soothing and thrilling. New modes of gratification were all around. There were lots of posters and walls of light advertising someone called Shiina Ringo, a Japanese female singer. In photos she appeared as nurse, nudist and Edwardian promenader. And in a big white wedding dress, holding a revolver to her own head. Alongside CDs and DVDs and video games, Shiina was also available as a series of model kits, with parts on plastic sprues, like something from Airfix. Shiina has explained how she took on her Ringo stage name (meaning ‘apple’) inspired by a graphic artist whose adopted name means ‘battle tank’. There were other tanks in Japan.

In the newsagents, alongside sweets called things like Bourbon Chocolate Every Burger, there were some immaculate little boxes. They looked like those individual packets of breakfast cereal for children. Instead they held meticulously detailed two-inch Nazi tanks – and a piece of chewing gum. But, as with football stickers and lucky-dip bags, you didn’t know exactly what you were going to get. I bought one of the boxes. It contained a Tiger tank, that much feared exemplar of Adolf’s armed might. Here was a strange little portal to the past. As with a fair portion of Britain’s post-war boyhood I’d been fascinated by the weaponry of the Second World War. Hitler’s tanks seemed particularly compelling, like even more blackly alluring versions of Doctor Who‘s Daleks. The most impressive model kits of tanks were made by the Japanese company Tamiya. The packaging was brilliantly designed, laid out with a mix of western and oriental script. They were expensive things, but a bit of skulduggery in the Carlisle branch of W.H. Smith could bring the price tumbling. At the time the shop’s price tags were handwritten circular stickers. By swapping a couple of stickers you could price-smash a massive £4.25 down to, say, 75p, around a week’s pocket money. Pre-barcode, the lady on the till would obliviously ker-ching through the purchase.

In Tokyo the tiny tank from the cereal box was accom-panied by a little comic. There were cute illustrations, like something from Richard Scarry’s Busy, Busy Town. There were also captions. A Japanese friend translated: ‘Caterpillar tracks allow tanks to go everywhere. Actually, they could not go everywhere.’ The comic featured a nice, smiling lady raising her hand to indicate the images. It looked like something you might get at a public swimming pool. Except she was wearing the trim blue uniform of a Luftwaffe auxiliary. A speech bubble extended from her mouth: ‘As time went by the pronunciation of “Tiger” changed in Japan from “Taiga” to “Tehgeru” to “Tehgah”.’ This accessible exercise in Japo-Germanic, mechano-Nazi linguistic mutation seemed emblematic of the alien allure sat just below Japan’s surface.

Over the next five days we would be garlanded with gifts and good cheer. When they played, BSP were received with amazement and delight, as if they were examples of some wondrous new fauna, hitherto lurking unseen deep in the Madagascan interior. It sometimes felt like we were minor deities, our mere presence bringing well being and joy. Either that or human interaction now existed on some beneficent new plateau, free from every memory of suspicion, jealousy and fear. Things had been different when our dad had come close to the Japanese people sixty years earlier.

Dad had been sent east in 1944 when he was twenty. He sailed from Liverpool aboard the SS Mooltan, a former P&O liner. There was the occasional poetic moment on the journey – the flying fishes flicking and gliding along the sea’s surface – but what Dad remembers most is trying to find somewhere to sleep. The ship was full and it was difficult to find a flat surface to sleep on. Once he’d arrived in India, Dad lived in fear of being sent to Burma where the Japanese lurked. Their reputation painted them as relentless, implacable killers. But Dad never really came within range of the Imperial Japanese Army. His service years drifted on, taking him to what was then Ceylon. Finally he was posted to Java in Indonesia.

During the war Dad would come to see a hen’s egg as something well worth walking ten miles for – five miles there and five miles back. Again he was manning anti-aircraft guns, but never once saw an enemy aircraft. After the war Dad rarely talked about the conflict with the sense of engagement that many understandably feel for this tumultuous period. Rather Dad seemed to have experienced the Second World War as a vast repository of ennui, absurdism and loneliness. Here perhaps was intergenerational priming in the melancholy and solipsism beloved of indie rock.

For a while Dad was stationed on the Cocos Islands, a ring of coral atolls out in the Indian Ocean – 1,500 miles from Sri Lanka, equally far from Australia. By the time Dad arrived there any Japanese threat to the islands had receded. But crabs sometimes engaged the British armed forces. Land crabs would come crawling through tents at night. They were harmless enough, but some of Dad’s comrades reacted by smashing them to bits. The shattered crabs rotted in the intense heat, giving off a foul, pervasive smell. Falling coconuts and giant centipedes brought more physical threat. The ocean held sharks and there were jellyfish with a bite strong enough to knock you unconscious. The seas themselves were treacherous. Towards the end of the war a succession of swimming airmen were sucked to their death in the reef currents.

After his time on the Cocos Islands Dad was sent back up across Ceylon and on to Madras. On the way through India the train came to a stop at a flat, featureless junction somewhere in the country’s seemingly endless interior. As Dad would recall, it was a strange, arid place. He remembered the train track running through the ground like a vein of silver through a banknote, but a banknote so tattered and filthy you wouldn’t even want to pick it up. An oppressive mood rose with the heat haze. The train would be there for hours. Dad’s fellow servicemen climbed out of the freight wagons. Water was siphoned off from the train’s boiler to make tea. A game of football started up. Dad wandered off a little way from the track. Rounding some bushes he suddenly came upon a single, solitary hut. As soon as his eyes alighted on this dwelling the door opened. A woman of indeterminate age came out. She looked directly, impassively into Dad’s eyes. Without hostility, with utter detachment, the woman’s gaze seemed to carry questions. ‘Who are you? Why on Earth are you here? Why?’ This brief, wordless meeting made a deep impression on Dad. For as long as I could remember I’d heard him recount the incident. It was a moment that encapsulated Dad’s war. He had volunteered as soon as he could. Thereafter he had viewed his own presence amid these astonishing events only with detachment and bemusement. ‘Why am I doing this? Why am I here? Why?’

By the time British Sea Power arrived in Japan, Dad had exchanged one form of AAA for another – the grave mechanics of anti-aircraft artillery replaced by rock’s access-all-areas pass. Instead of dreading dispatch to Burma, Dad was now reading about Mission of Burma, the Massachusetts post-punk group. The people we met in Japan seemed endlessly removed from the spectres which had haunted Dad’s war years – people made only of martial mania and an insistence on death before dishonour. In our Japan serenity and ingenuity seemed to reign. Vending machines sold beer, eggs and training shoes. We travelled on the bullet train from Osaka to Tokyo. Even aboard this miracle of metal and circuitry, charm and courtesy seemed crucial. My guidebook said

the bullet-train routes have ‘an annual schedule deviation

of thirty-six seconds, inclusive of the typhoon season’. As

we passed snow-capped Mount Fuji, a beautifully dressed woman walked down the aisle. Soothing music tinkled from the trolley she pushed. Green-tea ice cream was on sale. As we attempted to learn a few words of Japanese, this nation’s weave of decorum and politesse was hinted at. The literal meaning of arigato – ‘thank you’ – is ‘you put me in a difficult position’. Sumimasen, an expression of regret, literally means ‘this inconvenience will never end’.

Our Japanese record label gave us all beautifully wrapped presents. Mine was a large, high-quality art print. It was based on a painting of eight schoolgirls. They were graphically disembowelling themselves with swords – in the ritual samurai style of seppuku. Scott was given a Japanese headband or hachimaki. In Japan these are widely worn – by sports fans, by swotting students, by women giving birth.

But to us ill-educated Britons the headband most strongly suggested those worn by kamikaze pilots – as they drank their last glass of sake and prepared to fly off into eternity and nothingness. Eamon was given a sugegasa, the traditional conical straw hat you might see a farmer wearing in a rice field. From one perspective Eamon’s hat was puzzling.

It was all a bit like a Japanese band arriving in London and being given deerstalkers or policeman’s helmets. But the hat was also very thoughtful. Our Japanese label had noted how Eamon liked to – or was forced to – wear a hat on stage.

Eamon was a bit bald. From the outset I’d impressed on him to wear a hat when he was on BSP duty. Eamon didn’t particularly want to wear a hat. ‘But I’ve got a great-shaped head!’ he railed in protest. He did have an interestingly shaped head, but he still had to wear a hat. The skull beneath the skin makes people uneasy. Similarly sometimes the skin beneath the hair. U2 are always wrong, but their guitarist the Edge is right to wear a hat. Lights shining off a bald bonce on stage just get in the way, distracting from the main agenda. I tried to explain things to Eamon. I thought the fact I was pretty bald myself might help with my aims here. But it didn’t really. Eamon actually understood how some things shouldn’t be allowed to get in the way of rock. ‘Oh,’ he exclaimed, ‘you mean like Ian Stewart in the Stones with his lantern jaw. Didn’t they make him play behind a curtain?’ Eamon was talking about Ian Stewart, the Rolling Stones’ regular keyboard player, who was indeed kept well away from photos sessions. There was no curtain for Eamon. But he did, by and large, wear a hat.

It was wonderful to see BSP featuring in Japanese magazines. The way the articles could have been saying anything seemed thrilling. Here was a spell that could be never be broken by a damning review or some terrible factual inaccuracy. Translation from Japanese to English seemed full of endless implication and transformation. The literal meaning of ai no kesshou is ‘love’s crystallisation’. The actual meaning is ‘child’. Amakudari literally means ‘come down from heaven’. It also equates to a retiring civil servant landing a cushy job in a private company in the same sector. Japanese magazines, however, are almost always titled in enigmatic English. It was good to see several pages on BSP in the music magazine Cookie Scene. It was a delight to see a big picture of the band in Snoozer – or as the publication’s subtitle had it, ‘Magazine for girls & boys tangled up in blue’. The new issues of Snoozer and Cookie Scene were arrayed in immac-ulate city-centre Tokyo book shops. Alongside them was an amazing range of other magazines. There was Peach John, a kind of periodical underwear catalogue (slogan: ‘Lingerie is Love-Jewellery’). Fudge was a stylish fashion magazine. It was aimed at women, but the male population needn’t feel excluded. They could read Men’s Fudge. The Japanese mag-azine titles stacked up with a kind of deranged brilliance: Fine Boys, Footstyle, Happie Nuts, Woofin’, Ollie, Mewmew, Carboy. But beside all these there was an even more unusual print world.

There was a peculiar range of magazines that featured young women in school uniforms and other formal attire. One colour spread had a line of girls in skirts and sailor tops. The headline: ‘DREAMSWEETS’. At first glance it was difficult to understand who these magazines were aimed at – pubescent young girls or very post-pubescent old men. The girls weren’t salaciously posed. They stood in smiling formal lines, as if at school assembly. The magazines weren’t up on the top shelf in some shabby suburban newsagent. They were in chic high-street bookshops, out in the open, racked at respectable altitude. Nonetheless it seemed fair to say these magazines sat on the edge of some disquieting Japanese cultural backwaters – the oily expanses of lolicon and burusera. Lolicon is a Japanese fusion of the phrase ‘Lolita complex’. It denotes a sexual interest in pubescent girls, an interest catered for in a range of magazines and comics, often on general sale. Burusera are the shops that sell used gym outfits and sometimes underwear, apparently provided by young women.

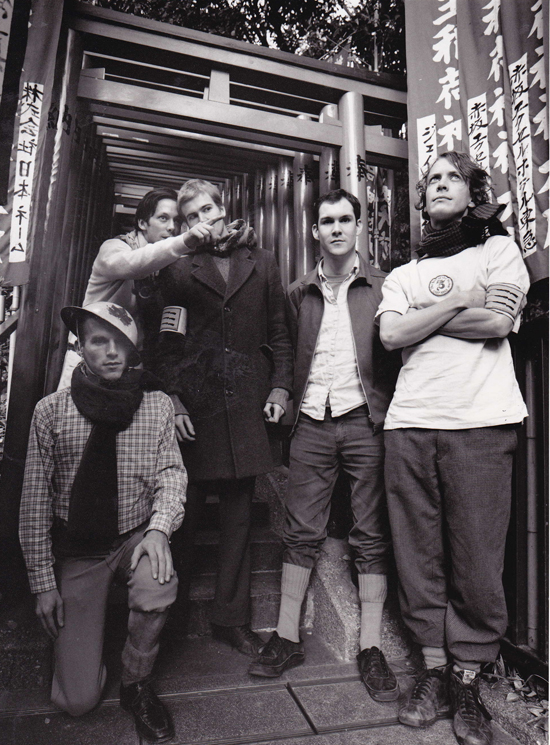

In Japan the BSP audiences included a higher proportion of women than we were used to, but no one was selling dirty underwear. There were ranks of striking oriental geometries, all aimed intently up towards the band. There were also smiles. Looking at photos from the shows, everyone’s faces are full of what seems to be a mix of glee and disbelief. The band are smiling before and after the show. The audience grin mightily as well. The band played well. Beyond that the memory is one of abstract joy and exhilaration in a land beyond the sea. But there is some physical evidence of the group’s commitment to live rock performance. By this point BSP were experienced stage vandals. At their early shows they routinely flung their guitars, drums and limbs into cataclysmic closing collisions. Neil’s bass rarely seemed to have more than two strings. Eamon’s keyboards were missing several keys, replaced by taped-on lollipop sticks. In 2002, as they’d prepared to make their debut at Reading Festival, my heart had jumped with pride. I peered across the stage manager’s clipboard and saw scrawled in big letters: ‘BEWARE! MAY TRASH STAGE.’ After the last show in Japan I was presented with some paperwork. There were two delicate parchments with ornate borders, covered in figures and oriental script. They were handsome items, like something you might have got at a hotel in the Italian Alps in 1957. But as I look at these papers today the elegance is compromised by my own scrawled handwriting: ‘Broken mic stand 3 2 / Broken mics 3 2 / Broken tweeter.’ The bills came to a total of 36,068 yen, about £270. It was money well spent.

We checked in at the airport the next day. Our plane followed a northerly route at 30,000 feet, across Irkutz, Novaya Zemlya, the Barents Sea. Below us were regions so severe you need a microscope to count the growth rings of the pine trees. Ground speed 555 mph. On across Anchorage and Godthab. Soon we were at Heathrow and on our way to more familiar places – Lewes and Seaford, Brighton and Portslade. Microphones had been broken, but the band was intact.

Do It For Your Mum can be bought online here