“Perhaps the most significant legacy of rap radio in New York is the fact that it was never really limited to New York,” John Klaess argues in Breaks in the Air. A fascinating chronicle of the emergence of rap on New York City’s airwaves, Klaess’ new book centres on the years between 1979 and 1987, from the release of the first commercial single to feature rapping to the widespread commodification of Black sound. But in his analysis of how artists and DJs adapted rap from a performance-based artform to a genre rife for dissemination, Klaess also sheds light on how such a localised form of culture could then emerge in places like Europe and the UK.

“We started listening to hip hop because Debbie would go to New York with her family in the early 80s, record the radio on a cassette tape and bring it back for us to listen to,” Cookie Crew’s Susan Banfield told me when I interviewed her in 2021. “We would listen to it at home, and it was amazing to us. We started to hear different styles of rap on these cassette tapes that were basically New York radio and we said to each other, we could do that so let’s try and write something.”

As Cookie Crew, Banfield and Debbie Pryce were one of the first female hip hop groups in the UK, pre-dating other prominent women in UK hip hop like She Rockers and Wee Papa Girl Rappers. Though their identity and style was undeniably forged in London, what was happening in the New York music scene was a clear inspiration and the initial spark that encouraged them to start writing and performing their rhymes together.

That Cookie Crew themselves give significant credit to New York radio reinforces Klaess’ argument in Breaks in the Air, that rap radio not only contributed to the growth of the local scene in New York but much further afield too thanks to the culture of acquiring, sharing and copying tapes recorded from the radio.

Klaess approaches the subject of rap radio with a clear passion and attention to detail, which is what predominantly enables the book’s various anecdotes and analyses, on figures like DJ Afrika Islam, Mr. Magic and Red Alert, to be so engaging. In the chapter on popular radio show Rap Attack, Klaess’ exploration of Mr. Magic and Marley Marl’s profound partnership in the studio (“smooth mixing, abrupt cuts, and longer, more involved stretches of mix”) delves into how such a show could be so influential to the genre, as well as to how hip hop could and would be adapted for the radio. As Klaess notes in his description of the pair’s wider impact, “Magic and Marley Marl helped pry open a door for political and cultural expression that may otherwise have remained locked.”

Aside from the emphasis on popular music, Breaks in the Air is also an interesting look at the era’s post-civil rights activism and how communities were seeking new and tangible modes of representation. Klaess’ examination of the popularity of shout-outs on the radio, for example, draws attention to how young people of colour could find affinity in the medium. “To hear one’s name in a shout-out,” he says, “was to be audible in a more nuanced way than ready-to-hand media languages for portraying race and poverty in America could capture.”

Klaess traces the commercial growth of rap, profiling small community stations as well as the stations owned by New York’s African American elite, and the rise of the “urban contemporary” label. In doing so, he highlights how hip hop developed from the underground and from club culture to something worthy of the recognition of advertisers, sponsors and as a result, large sums of money, as it did in the wider music industry.

The context provided throughout, on subjects like broadcast deregulation and radio ratings methodologies, may seem superfluous at first but they assist in painting a more thorough picture of the fractured landscape within which hip hop was starting to exist and thrive. Klaess also skilfully explores the scepticism with which many viewed hip hop – not as a cutting-edge form of Black art but as something to be censored and disavowed for its lack of “respectability” or as Klaess describes, “either an expression of Black creativity or threat”.

In the book’s ‘Preface’, Klaess mentions one of his first conversations with Chuck Chillout and how the DJ told him that he would only consent to an interview because “a lot of guys are getting left out.” He continues: “He’s right. Rap has a pantheon and a canon. I hope this history has broadened, if only a little, the kinds of stories that constitute hip-hop and radio history.”

A book that tells the story of rap on New York City’s airwaves, Breaks in the Air is mandatory reading for anyone with an interest in hip hop history and elements of that history that aren’t readily considered, including figures responsible for its early dissemination. As well as providing a meticulous account of the first stations to air rap music, Klaess’ book offers a unique insight into the sociopolitical power of broadcast media and how alongside the growing popularity of hip hop, radio provided a valuable new avenue for Black expression.

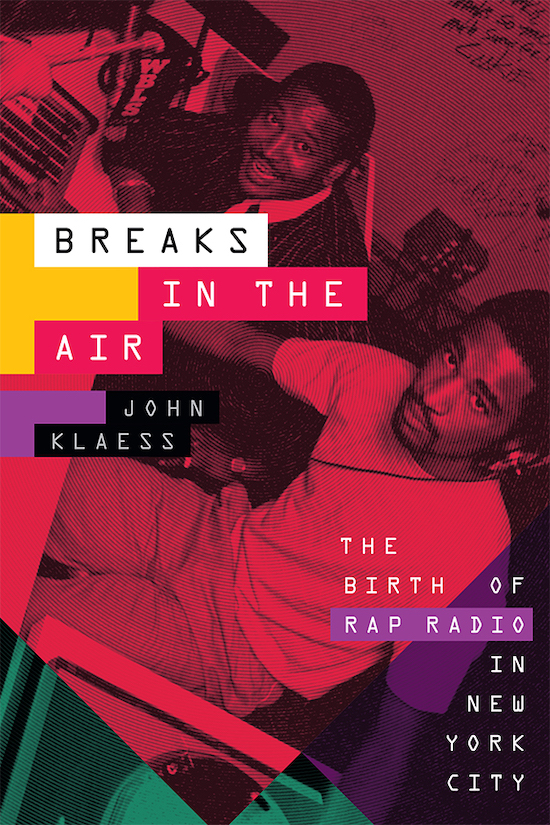

Breaks in the Air: The Birth of Rap Radio in New York City by John Klaess is published by Duke University Press,