A good title need not be archly complicated, profoundly revealing, or even relevant; but all good titles seem to ring out gracefully like the melody of fictional youth: Catcher in the Rye, A Clockwork Orange, The Executioner’s Song, Less Than Zero, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please, Happy, Like Murderers. Weighted perfectly, each, in their own stylish way, say everything you need to know about the book, without straining to be recognised or resorting to witless platitudes.

Taken from a sample at the start of The Chameleons’ first album, Script From a Bridge, The Last Mad Surge of Youth, is another one of these perfectly weighted titles. Coupled with a fittingly nostalgic book cover, all at once you’re dealing with an attractive proposition. To the select few in the know, this will come as no surprise: Pomona have been publishing some lovingly distinctive pieces of writing ever since the author of The Last Mad . . ., Mark Hodkinson, realised the publishing world didn’t have a place for his taste some five years ago, and so embarked upon creating his own, small — but not small-minded — publishing outfit.

A quick glance through their back catalogue throws up a bunch of writers who could easily have withered away like fly-blown newspapers left to the elements, but for Hodkinson’s tasteful foresight and unflagging enthusiasm for reissuing them. That is: writers like Barry Hines, Ray Gosling and Trevor Hoyle; succinct stylists each with their own unsparingly considered take on England, on the state of England, in all its wearied glory. For this alone, Hodkinson has won a few fans. Sadly, it takes more than a few fans to keep the determined wolves from the door, so it’s been a struggle.

Ironically, various forms of ‘struggle’ rove the pages of this book, which itself took 15 years to finish: class struggle, money struggle, friendship struggle, love struggle, fame struggle, ethical struggle, addiction struggle, even weather struggle — ‘It was the time of year when bonfires burned in fields and back gardens, as if it wasn’t enough that summer had ended, it had to smell like it too.’

It’s all in there, channelled through a series of telling flashbacks set in the early days of indie music — Echo and the Bunnymen, The Chameleons, The Teardrop Explodes et al — the episodic nature of which perfectly mirrors the drink-shot mindset of its lead character, John Barrett, a working-class musician who achieved his teenage dream of flight and fame over the thin life, and the thankless cycle of ordinary decay.

Its downbeat tone has a resounding quality similar to that of two other richly bleak tales of crumbling musicians from interestingly impoverished backgrounds who can’t bear the unstoppable reality of their own myth-induced end: Stardust, starring David Essex, and I Am Still the Greatest Says Johnny Angelo (there’s another one of those titles) by Nick Cohn. Both of which, like The Last Mad . . . star composites of musicians: Billy Fury and John Lennon in Stardust, and P.J. Proby and Iggy Pop in I Am Still . . . . Burdened by his own melodramatic notions of doom, and warring with his own sense of conferred sadness, Barratt could be seen as a collage of the likes of Mark Burgess (The Chameleons) and Ian McCulloch (Echo and the Bunnymen).

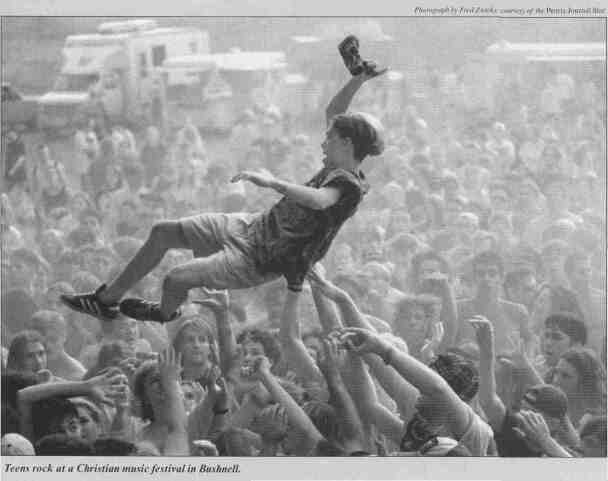

It’s as if the minutes are connected differently for him. Indulged the way that only musicians can be, he’s unable to inhabit his adult skin with any sense of responsibility; like the kid on the cover, you get the feeling he’d rather just keep on running in search of new ways to use that Northern nowhere of his youth as a reason to remain outside of the stultifying norm.

Looking back, the post-punk generation may well be the first generation that can’t quite believe they’re going to age, or that life is sometimes different than the lyrics of heroes from previous days — and Barratt’s heightened sense of injustice and self-pity is but a manifestation of this common malaise. If so, Hodkinson’s take on the fragility of ideas and ambition and self-worth in the ‘real world’, as they called it in school, is a beautifully humane one. And if, like me, you have a habit of lending your new favourite book on the pretext of not getting it back, you may think twice about letting this new Pomona beauty out of your sight.

About the Reviewer:

Austin Collings is one third of Brollywood Productions. They are currently in pre-production with their first feature film, Nocturnes. He was also the ghost-writer responsible for helping The Fall’s Mark E. Smith put the world to rights in his autobiography, ‘Renegade’.