If I’m honest, I don’t know a hell of a lot about poetry. Only what I like. So this column would almost certainly expose my limited knowledge should I attempt to review the work of poets I am showcasing. Instead, I would prefer to come at it from a different angle, like a crab, or a ghostly jellyfish, gently drifting up from the weird darkness towards the light of great work.

Melissa Lee-Houghton’s poetry is great work. Her writing makes me want to write, and write better.

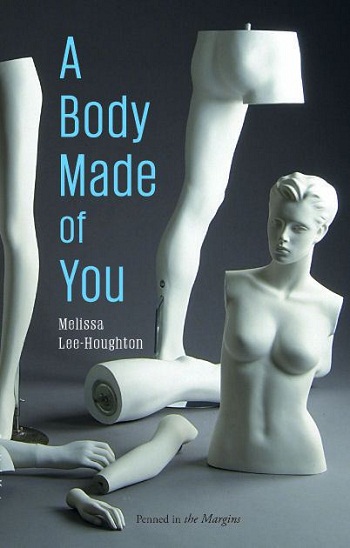

When I read the opening lines of her debut collection A Body Made of You I knew this was a monumental moment for me:

There’s room for carelessness; bodies

Thrown like Jekyll’s teeth

I felt a tingle of inspiration, the warmth of familiarity, that almost narcotic rush one feels when colliding with a kindred spirit. It is haunting, disturbing and intense. It is passionate and heartbreaking. The books I had been reading were failing to connect with me. I wanted to be punched in the chest. A Body Made of You did just that, and more. It damn near stopped my heart.

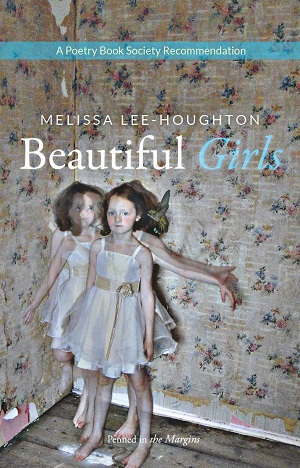

Melissa and I began corresponding. She sent me an early draft of her forthcoming collection Beautiful Girls and I immediately called my wife and read her some of the poems, reciting them with as much enthusiasm as I would my own.

Finally, I thought (after months spent reading poems that confused me), a real poet.

I recently, and rather drunkenly, explained to a friend my definition of a ‘‘real’’ poet. Not wanting to come across as arrogant or dismissive of people who don’t share my outsider beliefs – and not particularly regarding myself as a real poet either – I said imagine you are watching someone walk across a wire, perilously high above the crowd. Their skill is impressive, but there’s a safety net… A real poet doesn’t have a safety net. Beauty is dangerous. It has to be.

Am I talking out my arse? Probably. But I hope you understand what I mean. If you don’t understand, or you totally disagree, that might be a good thing: there’s plenty of poetry for you. You must be easily pleased, and I envy you that.

If you could be any other poet (living or dead) for a day, who would you be and how would you spend your time?

Melissa Lee-Houghton: I’d be Frank Stanford on the last day of his life. I’d get up in the morning and dig a four foot deep hole in my garden and bury my gun. Then I would drive, listening to the radio, smoking, and I’d go to a diner and have an imaginary meeting with all my favourite dead poets until we’d reached some sort of conclusion which meant I didn’t have to die. I would call my wife and tell her ‘baby, I am going to come home and break your heart,’ but I’d also tell her it didn’t mean we couldn’t fix it again. I would go home and watch her cry for hours, answering her questions and making no promises. I would pour myself a bourbon and sit out at dusk, itching for my gun but unable to go to the lengths it would take to retrieve it.

The word “blood” appears in almost all of the poems in your first collection A Body Made of You…

MLH: Blood has been an obsession of mine since I was little. The first time I remember seeing it (though it probably wasn’t the first time) I was very young and my sister cut her hand on broken glass, climbing some railings. A neighbour brought her home and my mum was trying to stem the bleed and I thought to go and get her all my socks. We put socks on her hand and she smiled like she was better, the red blooming through the little white socks. I also remember my step-granddad’s dog being on heat and licking at its bloody fur and this troubled me deeply, because no-one would explain. As though there was some shame in it. I’ve always had to censor myself by covering my arms; I self-harmed all through my teens and most of my twenties, something I don’t think is uncommon. I always cover my arms not just to spare my own shame but because other people react with a sort of revulsion or irritation when they see them. Self harm is a very private addiction. Some people do it for the pain, or the release through pain;I did it for the sight of blood. It always shocks me. Even just a little bit of blood, it moves me. When I was in pain, the sight of blood numbed me more than anything else. It’s the rhythm, the pulsing, the beating heart pumping. The taste of it, the smell of it fascinates me. It’s life, it’s terrifying. When I’m on my period, I feel like a different person. Almost like one I should hide away. It’s interesting now that after all these years of abusing my body I can’t watch someone take blood in a syringe. If I look at the syringe I start to go woozy, the sight of the hot blood coming out of me makes me faint.

Would you agree that, as a writer whose work deals with difficult, intense and deeply personal experiences, there is more at stake when you write a poem, that you take more risks?

MLH: I feel, frankly, exhausted (but excited!) by this new collection [Beautiful Girls] and I haven’t been writing properly for some time. I find it hard to edit, I have to leave large gaps between editing phases, because I can’t stand to read a lot of it, and I’m so self-critical that my worry is always that I’ll just annihilate it. I have written about things I simply can’t talk about and probably will never talk about again, to anyone. So yes, there’s certainly risk-taking. And it’s so easy to fail to elevate these risky poems beyond storytelling or a heady account. I don’t know if I’ve always managed this. It’s also difficult because it often seems as though so many people dislike autobiographical poems. It’s very much a balancing act and just a firm belief in what you are writing. What is at stake? Well, when you consider it rationally, not a great deal. I’m not going to die. I’m not going to be held under house arrest or murdered for the things I have to say. I’m more sane when I write than when I don’t. If all of the population read my book and only two per cent liked it I’d still be happy with it. Of course I would. It’s not a bad ratio.

Have you ever been embarrassed by your writing, afraid of family or friends reading your poetry, or people judging you?

MLH: I’m not so bothered about people judging me, but I think that comes with experience and age. I have only recently been feeling this way, having been around a few years and having realised the world is full of massively opinionated people and, well, I don’t really care. I have always been worried about family hearing me read my poems: there are some which are intensely personal, and although I think they can probably handle it, it brings back very real memories for them, and I don’t want that for them. I always feel embarrassed by my writing, stuff I’ve done before when I was young and naive, and I just have this in-built, very exaggerated sense of humiliation. I worry about being exposed. I worry about messages getting leaked and people reading my medical notes and friends sharing our personal conversations between themselves. I’m not worried about what they think so much as simply losing that control, over my privacy, which is a right we should all have. Possibly it’s indicative of the age we live in that I’m so paranoid. I recently destroyed many years’ worth of work so that nobody will ever be able to read it. I don’t want too much of what I’ve written lying around when I die. Your thoughts and your emotions change so dramatically through the years more often than not, when I read something I wrote years ago, I feel nothing whatsoever, or maybe a slight tinge of sadness and disappointment. I don’t know why but I was initially very affronted by the concept of my worrying about people judging me, but by admitting it I was worried that people would judge me. Whilst writing this it has become apparent to me that I have a latent fear of being judged.

Everything you have written is placed into a magic box and dropped into the sea, where it transforms into something else. Later, it is washed ashore. What does it look like?

MLH: I’ll go with the first thing that came into my head, though I so wish it was something else. It would be a newborn baby. It would be howling with hunger, and white as a sheet. It would have little red feet and hands and it would smell unloved. And my hope is that someone would come and find it on the beach and nurse it, and it would probably grow up undeterred by this unfortunate incident in its life. Probably. And if not it might grow up to be a poet, and write some books about the sea. But more likely it’ll carry my blood which will start to warm up as it gets older and someone loves it. I think I will be dead by this point, and will never have expected it to survive. And maybe it won’t. But while its blood is pumping, I’ll sleep there in the ground with my eyes open.

List of good things about being a poet.

MLH: I have a shiny leather writing briefcase/satchel; mahogany with gold trimmings. I have only used it once, and it was awkward to fit anything into, but I have one. And that’s important.

The immense pleasure of putting certain words in certain orders is so ridiculously wonderful I can’t understand why everyone isn’t doing it. And really, if you’re not, you have no idea how elated a person can get over a few syllables and a bit of alliteration.

Notebooks. I use black ones. But I just bought a red one and it feels a little risky.

Being able to carry so many words/poems/lines inside you, some of which you can access while going for a walk or sitting down with a cup of coffee. I feel that the language comes from my chest. I feel it where the anxiety and sadness and excitement is.

List of bad things about being a poet.

MLH: Never being able to afford all the collections you want.

Being a disappointment ‘in the flesh.’

A perpetual sense of inadequacy regularly confirmed by the daily conditioning of social networking.

No being able to write ‘on command.’

Could you tell me something about these words please?

Drugs…

MLH: I take: a Depixol injection, Lithium, Lamotrigine, Procycladine, Promazine, Zopiclone, Diazepam and Citalopram. When I’m dangerously high, Depixol flattens everything. I don’t love it and I can’t hate it. I live in limbo. I’d have to say with some certainty that most experiences I’ve had of getting high were comparable to a full blown manic episode, highs and psychotic mania, in fact, in most cases, my absolute peak in terms of mood were far in excess of any drug I’ve ever taken. When I realised the highs no longer meant euphoria but agitation, paranoia and pain, I had to give in and start popping the pills. Sometimes they make me sick. They make me fat. They do weird things to my body in general. A lot of people think I’m just really weak or something. Whatever, my brain chemistry is probably so much more bizarre than ever.

Music…

MLH: I listen to music just to get by. I can’t even walk anywhere without listening to music, I constantly ruminate if I am not distracted. I like to play a song on repeat if I am in the mood, I love repetition. I love how the song fashions a groove in your mind and playing it over has a familiarity and a catharsis I can’t get from anything else.

Knots…

MLH: I have quite knotty hair. When I was little I remember putting knots in my hair on purpose so that my mother would have to cut them out. I have no idea why I did this. My sister and I used to play ‘cat’s cradle’ with my mother’s wool, but mine always ended up hopelessly knotted. I have practiced knots, nooses, in my teens, like Plath in The Bell Jar, and the image of a noose puts me into a panic. If I see a hanging scene in a film I feel like someone has plunged me into icy water. It is the fear of something I was once so close to being accepting of. It is the fear of something which has accounted for a lot of misery in my life.

Dreams…

MLH: Last night I dreamt a violent man with missing teeth petrol-bombed my house killing everyone other than me and I didn’t want to live. When I was very ill I dreamt nightly that I was executed to a baying crowd, a different method each night. I didn’t want to fall asleep. I would let my husband see me take my Zopiclone and when he dropped off to sleep I’d go downstairs and sit in a chair and hallucinate that really kind other-worldly, wobbly, ghostly people came and patted me on the shoulders and smiled at me and kept me safe. There have been times in my life when a dream was so prominent, or so vivid or inspiring, that it initiated something, a change, a phone-call, an idea. Throughout my childhood and into my adulthood, I had a recurring dream of a ‘sandman’ who would chase me through the desert, and in every single dream I would reach the point where I knew I couldn’t outrun him, that there was nowhere to go, and would have to decide whether to stay and fight or stay and let him hurt me, hoping always that he’d kill me quickly. My ‘good’ dreams are surreal, quite ethereal and often sexual. Mostly, I don’t remember them for long. I bought a poetry collection by a writer I knew little about but ‘knew’ on Facebook, on the grounds that I couldn’t stop having dreams of them. It was a good call. It’s really an excellent book.

Beautiful Girls…

MLH: I’m immensely proud to be a woman. I love all my favourite girls. When I was having my first baby, at seventeen, I was terrified I would have a girl and that she’d suffer the way I suffered. I didn’t even dare pick out a name for her before she was born, but when I saw her her name just rolled off my tongue.

Fettered Heart

They don’t know what it does to my brain.

I don’t feel it, wet and thin, lubricating,

sliding in and out of holes that have been there

since I opened my mouth.

The lord moves in mysterious ways.

He gives me an injection every week

in a chaotic clinic full of the clinically insane

who are in shock all of the time.

Melvyn stares at his appointment card

for ten minutes. He tells someone his dad is dead.

He is eager to get his injection

so he can go shopping, and maybe today he won’t cry.

All of the women are fat.

The nurses don’t have to be so careful with the needle.

Plenty of room in our buffalo behinds.

The drugs are stored up in red, raw muscle.

I have a stiff mouth, I am curt.

I can’t go back to listening to Death’s answer-phone.

I can’t go back to arching my back like I’m falling

out of an aeroplane; the contortions, the shape-shifting-

the hospitals, the pills, the vomit, the hallucinations,

and the locked doors, the stale beds, the absence

of myself. And the rain today is freezing just as soon as it settles-

I have been skidding around like a lunatic in my plastic shoes.

I am attuned. I bleed out.

I pick up on rhythms, abnormalities-

I pick up on the language of gratitude and servility.

And I am not a pretty girl.

We are not pretty people. We are living like the slack-jawed fish

that swim around coral reefs, being maintained-

I wait patiently, every day, for something to prove this ordinary

life is part of something extraordinary.

Nothing happens. I take the shot, I whip up

my knickers, they ask me if I’m well and I say well, yes.

I am not connected. There are no ordinary words for these things-

I am not connected to the world as in outside my head

or the world as it is inside my five year old son’s brain.

I could easily believe that nothing bad will ever happen.

Maybe the strength of our delusion is the true test of real happiness.

My son announces when he grows up he’s going to get rich

while Melvyn at the clinic is content with being presentable.

He wears a shirt and tie on an average day,

no employment, no place to be.

Nowhere. I think I admire him.

There are old tears swimming in my head like larvae.

I would pluck each one with tweezers-

I have tried to extract them before,

sad songs, bad poems, the five o’ clock news-

streaming like radiation. I don’t wish for damnation

but I haven’t cried in three years and my eyes are dry

and the drugs have settled in the ducts.

I piss antipsychotics. I piss tears and tea,

endless tea and endless darkness winding around my veins-

when I walk to his school I imagine falling

on the ice and breaking all my bones, and having to

get onto my broken knees with my broken hands

and my wrists snapping and my head caving in.

I imagine this broken person walking into school

scaring the shit out of all the children,

bits falling off. An ear, a crumpled finger.

But I don’t break. I stay fat and whole like an almond

left out of the pan. Everything’s contagious. You should know

that should I come to your house with a loose tongue

and five species of Amazonian birds to peck at your head

you will catch something. You will find it in something I said.

I have worked hard at living. You don’t have to

work so hard at death. I have enough sleeping pills in my house

to kill myself. But it’s not the dark that shames me;

I am see-through, flat shoes and a coat

that puts on two dress sizes. You don’t smile back

because my lungs are on the outside, heaving.

Nobody wants to see that.

Everyone is too polite to say,

and I bleed into my pockets and it dribbles

onto the pavement and from my nose

and I just imagine myself in white

with white blood and white kidneys.

Melvyn doesn’t mind. He sees his own insides all the time and he

smiles fondly at mine. The glitter in his blood is the residue

from the drugs, collecting, sparkling.

People these days don’t know what they want, they aren’t even aware of

their own mortality; they can get in a car dreaming

of California, hot women and hot sex.

They can cross the road striding like the Beatles did.

I know what I want. My brain free again, not held

hostage; not tortured, force fed. If I am to be mad

then so be it. Those hospitals cannot keep me anymore,

I have outgrown them, outwitted them, they’re not so clever,

those doctors cannot rein me in. My son is drawing

birds with crayons. He’s colour blind.

My world is not fluorescent today. Here, there is no colour-

no competition with the sun;

see how I shift through time and space, it’s magnificent.

I can be anywhere. This chair, this table;

a whole week. A week like the lining up of pills

on the bedside table. The bulb burning out;

lying on my back in the dark thinking about stars

and death, and death and stars.

I am not mediocre. But nobody knows what it does to the brain.

Nobody knows what they’re doing.

Melvyn skips mentally along down the road to his favourite shop

where the check-out girl smiles and his shirt has no creases.

I pine after my husband to come and save me before I rip

my hands open in the kitchen scourer,

washing and washing the bloody place as though

madness has infected it. The air outside is crisp.

They keep telling me it’ll snow but it doesn’t.

They keep telling me it’s all to make me better-

the taxpayer pays for my drugs. I am emotionally inarticulate.

No fights to fight just getting rest, emotional regulation

free from stress, no phone-calls, no excitement. This is dangerous,

this is dangerous. From nowhere-

I fall off the doorstep. I fall off the bed I fall

from the passenger seat, I fall on the shop floor I fall

down the staircase, I fall in the street

I fall down in the clinic, I fall from the sky-

I land on my head, on my head, on my head.

Beautiful Girls is published in November, by Penned in the Margins. Her debut collection A Body Made of You is available here