First drawn to what he calls the "spaces and cultures of weird music" by DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing, David Morris has been writing on the subject for the last decade. Blown Horizonz, his first book, is an ambitious Frankenstein’s Monster of music writing is part travelogue – part hauntological discourse and a great many things in between, it is, above all, an exploration of the fringes of music in which Morris has found his comfort zone.

Asocial Distortion

Did, didn’t, I can’t feel nothin’, superhuman . . .

Even when I’m fuckin’, Viagra poppin’, every single record, autotunin’

Zero emotion, muted emotion, pitch corrected, computed emotion.

-Frank Ocean, “Novacane”

I grew up in a world laid over with a low-fidelity digital filter, barely able to sense the subtleties of human vocal inflection, body language, suggestion. If I were thirteen today, I think I would run the chance of ending up on the autism spectrum. Or maybe I was just a little more alienated than your average teenager—all I know is that I had a very hard time making friends, spent a lot of time in my room, and didn’t have a real girlfriend until after college. I knew I had a problem—maybe that constant discomfort was the sign that I wasn’t really broken—and I did understand the power of learning, of self-improvement, of looking for models and blueprints. Hip hop became part of my self-improvement program, a map of where I wanted to go and who I wanted to be. It gave me a vision of what it meant to be normal and happy. This meant being confident, easy around people, moving with swagger through parties where your presence was a blessing.

I went to hip hop shows, drank, smoked, danced, did what I was apparently supposed to do to connect. Drinking got me out of my head and talking to people, whose names I would not remember the next morning. I eventually discovered that women were easy to talk to when you pretended they didn’t matter, and that apparently at least some of them thought I was good-looking, funny, charming. I didn’t feel at all qualified to make these judgments about myself. A lot of friends came and went, easily made and easily parted from. For all my striving there was some barrier I could see, but couldn’t get through.

The 18th and 19th centuries were what is now known as the Age of Enlightenment. Western societies of that time were enthralled by the idea of mankind’s perfectibility, his fated control over the natural world, ability to dominate chance and rationalize society. The 20th century, zombie-like, shambled forward under those delusions even as they were battered by wars that made no sense, science discovering the edges of predictability, and natural disasters that laid grand ambition low. Our current Great Recession may be the final reckoning with the end of the Enlightenment, with the death of humanity’s infinite power. We now know that our universe is full of nonsense, of randomness and uncontrollable forces, of insuperable obstacles. We have learned, after centuries of striving towards utopia, that we ourselves are the biggest obstacle. But we haven’t quite figured out how to live with that.

In the 1980s, the hangover of Enlightenment, the Exxon corporation was using sound waves to help map the subterranean world, as part of an attempt to understand the underworld, navigate it, find oil for the betterment of mankind. One of the engineers performing this seismological analysis realized that similar processes could be applied to audio recordings—and that is how Auto-Tune was born.

Auto-Tune was first used as a behind-the-scenes way to smooth over small errors, both live and in studio, and used as intended, it is inaudible, existing only as the lack of imperfection. But in 1998, Cher’s single ‘Believe’ became the first pop song to reveal the man behind the curtain, to make Auto-Tune not subject, but object. As Sasha Frere-Jones put it, the use of Auto-Tune in ‘Believe’ represented “a controlled version of losing control, hinting at various histrionic stations of the human voice . . . without troubling the singer.” While T-Pain became synonymous with the overt misuse of Auto-Tune by turning it into a cheap gag, this sense of detachment is where it has been put to most interesting use. On Kanye’s 808s and Heartbreak and Bon Iver’s Blood Bank EP, Auto-Tune was both a screen and a net, there to catch singers dealing with such intense material they seemed perpetually about to fall into the farthest abyss. Its detachment meant safety.

But at the harder edges of hip hop and R&B, in an underground realm continuous with the weird rap blowing up the blogs, Auto-Tune is the abyss, just one part of a world that has left us not with too much to feel, but far too little. When Lil’ Wayne laments how hard it is to learn how to love, and does it through a curtain of bending circuits, it highlights rather than smoothing over the jagged edges of the desiccated digital world we live in. On tracks by The Weeknd, singer Abel Tesfaye’s voice has a perfection that is cutting, authoritarian, utterly obscene. It’s the kind of voice that feels like it deserves to talk a girl into taking drugs and doing things she doesn’t want to (‘High for This’), and later declare, half-convincingly, that it doesn’t even care about her enough to be upset that she cheated (‘The Knowing’). Auto-Tune is just barely apparent on these songs, present only as a kind of hollow, medicinal ring, as part of an overarching universe where fakery, performance, drugs, porn, and hedonism have sucked all the joy out of the room, even as we keep going through the joyful motions. The emotional intensity that Tesfaye’s epic performances should deliver remains just out of reach, and that distance is highlighted, pointed at, making The Weeknd a complex satire, meta-music aiming its subtle guns at monomaniacal sociopaths like R. Kelly.

We can only go so far convinced that something is working when it’s not—the faster we do it, the higher the evidence against it piles up. My anxiety and alienness smoothed over by liquor and loud music, I learned to make something like the right gestures. It became easier and easier to get people to do things they didn’t want to, until I eventually realized that most people had no idea what they did or didn’t want. Eventually you realize that your memories are of sensations, of images, frozen moments of intensity, drained of any emotion except possessiveness and power. It’s happening to all of us now, hung over from a two-decade fantasy of unstoppable economic conquest—a thing based on mutually-held delusions, lies we all agreed not to point out. The gloss is off our floss, as the desperate and disastrous efforts to maintain Wall Street’s dreaming provoke greater and greater anger. American Psycho seems less metaphorical by the day —who but an utter sociopath, after all, could take a million-dollar bonus after sending millions into poverty?

Sometimes the only way to critique the insanity of excess is to quote it back to itself. The Swedish soul duo jj turn the mantras of hip hop conquest into dirges even bleaker than The Weeknd’s, with Elin Kastlander’s louche, rumbling vocals replacing defiant hype with morose horror. “I’m grinding until I’m dying/ They say you ain’t grinding until you die. So I’m grinding with my eyes wide, looking to find a way through the day . . .” Sometimes our struggles to get out of the trap, become the trap—take the girl in Frank Ocean’s ‘Novacane,’ an aspiring dentist who “[pays] for school doin’ porn in the Vall,” and can only get her head out of one job through another, recreationally blowing her brains out with medical fringe benefits until she can’t feel anything. Danny Brown’s ‘Die Like a Rockstar’ boasts nihilistically about partying “River Phoenix ’93 VIP/ with some drugged up porn hoes all around me.”

We’re learning that we can’t save ourselves—not with technology, training, medicine, upward mobility, learning, planning, perfection, surgery. That’s what I finally learned sampling is, by the way—cutting and extraction, removing sound and making it mean something else. DJ Shadow opened up bodies, sewed them up seamlessly, made them live again beautifully, if a bit strangely. Today’s most arresting producers make their beauties ghastly, machinic—Clams Casino, AraabMuzik, Holy Other, and many more pull vocals (usually female) out of context, clip off heads and tails, and turn the affectless remains, robbed of inflection and context, into distant melodies. The samples are posed, like audio mannequins or sex crime victims, into macabre imitations of life.

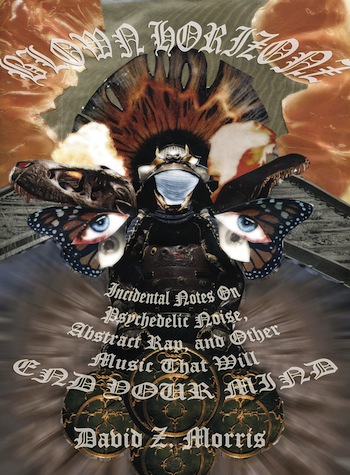

Blown Horizonz: Incidental Notes on Psychedelic Noise, Abstract Rap, and Other Music That Will End Your Mind is available now, as an e-book

David Z. Morris has written about music, culture, and politics for publications including Maximum Rock n’ Roll, The Japan Times, and Signal to Noise. He blogs at mindslikeknives.blogspot.com, and you can follow him on twitter @davidzmorris

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more