Paul Ryan and the late Jon Kennedy of Cradle of Filth/Hecate Enthroned in the mid-90s. Photo courtesy of Paul Ryan

The history of black metal in the UK is one of mountainous highs and chasmic lows. On the one hand it can be argued that Britain holds the ultimate responsibility for the creation of black metal – and indeed, all forms of extreme metal – having not only given the world the mighty Venom, but also Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, Motörhead, GBH and The Exploited, the bands most name-checked by the 80s black metal pioneers in this book. No UK, and heavy music as we know it simply wouldn’t exist. Yet after the early efforts of the Newcastle powerhouse, there were extremely sparse offerings for almost a quarter of a century, the situation finally being remedied during the 2010s, with the UK becoming one of the more significant countries in the genre in a relatively short period of time.

In terms of chronology, the birth of black metal in the UK post-Venom effectively took place when Cradle of Filth left their death metal roots behind, the group playing music that was undeniably black metal in nature from 1992’s Total Fucking Darkness until the late 1990s. There are a few bands that are occasionally argued to predate this, but frankly, they are not convincing arguments. The Newcastle band Ragnarok, for example, are definitely worth a mention, having formed in the late 1980s and dabbling in black metal in the late 90s. That said, their first releases, two demos from 1991 and another from 1995, take their cues from later Viking-era Bathory and Skyclad, resulting in a sound that is much more pagan/folk/thrash metal (and even hard rock) in flavour.

A group called Witchclan meanwhile describe themselves online at the time of writing as “The UK’s oldest active black metal band, est. 1990,” but their first tapes are from 1993 and they seem to have been completely unknown to the scene before retrospective social media promotion began in the early 2010s, the only material available to hear today being recorded during this era. Dead Christ are a much more compelling possibility, forming in Bristol in 1990, releasing two demo tapes in 1991 and a 1993 EP on none other than Greece’s Molon Lave label. The first demo is heavily grindcore-inspired, opening with a sample of ‘Everybody Dance Now’ and featuring several songs that only last between 10 and 20 seconds and perhaps revealingly, the thanks list includes bands like Agathocles and Sore Throat. That said, the rest of Dead Christ’s releases are certainly black metal in feel; unrelenting, eerie and primitive, and largely in the vein of Hellhammer, VON, Beherit and Blasphemy, with some of the pseudonyms used (not least ‘The Eternal Worshipper of the Seven Churches of Necromancy’ and, more amusingly, ‘Nocturnal Desecrator of Cack Infested Corpses’) suggesting heavy inspiration from the latter.

But as in many other countries, the British scene would only really begin to show signs of life from 1993 onward. The Cradle of Filth and Emperor tour of the UK that year would see the two bands accompanied by an early and short-lived UK black metal band called The Fallen, who issued a decent Scandinavian-style black metal demo that same year entitled Rebirth of the Ancients, splitting not long after. The scarcity of other native black metal bands at this time was underlined by the fact that doom band Mourn also acted as a support act (which famously led to the band’s onstage crucifix being smashed backstage) and the absence of active black metal bands in England during the early 90s would leave Cradle somewhat isolated in their formative years.

“I think we always were left to our own devices because there was never a scene to adhere to,” Dani told me back in 2007, “at one point there were bands like Anathema and I really think England took pride in that massive doom metal scene, but since then it’s been few and far between and I kind of missed it along the way. I would have liked to been part of a ‘UK black metal gestapo’ or whatever, but unfortunately it wasn’t to be. We were friends with a lot of bands; I was writing with Euronymous for a while, obviously Emperor, Necromantia, Immortal, Dissection we toured with, so we weren’t without our acquaintances, but we were left alone, separated from mainland Europe by an expanse of water. I don’t think England was ready for black metal at that point.”

That might have been true, but it’s worth noting that the UK did continue to maintain the significant position it has traditionally held within the music industry during these years. Aside from boasting the biggest commercial success in the genre via Cradle of Filth, it was also home to more significant record labels than any other country during the 90s, most notably Peaceville (Darkthrone), Cacophonous (Cradle of Filth themselves, plus Gehenna, Dimmu Borgir, Sigh, and many more), Misanthropy (Mayhem, Burzum, Arcturus and Primordial, to name a few) and Candlelight (Emperor most importantly, plus releases by Enslaved and Havohej). Later in the decade the labels Supernal (Drudkh, Fleurety, The Meads of Asphodel) and Blackened (Hecate Enthroned, Amsvartner, Enthroned) would also come to the fore. Just as importantly, many of the most influential metal magazines were English, not only Kerrang! and

In terms of homegrown talent, the first notable examples post-Cradle were Thus Defiled, Ewigkeit and Old Forest (all from Sussex in the south of England) and Hecate Enthroned, who hail from Wales. Bal-Sagoth are another popular group worth mentioning here, but though they are excellent and certainly had plenty of interaction with the black metal scene (signing to Cacophonous and later touring with Emperor) their sound and aesthetic only partially overlaps with black metal, and that was mostly evident in their early days. 1993 demo Apocryphal Tales and 1994 debut full-length A Black Moon Broods Over Lemuria are the most relevant releases within this context, though the band arguably went onto greater things with later works.

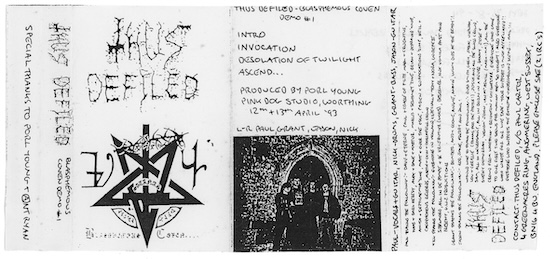

To be fair, Thus Defiled (originally Unholy Deification) were hardly a pure black metal band either – at least in their early days. Forming in 1992 and releasing their two demos the following year – Blasphemous Coven and Enchanted by the Dark One – they initially utilised death metal style riffs and vocals, alongside cavernous Blasphemy-esque brutality and some extremely slow and doomy passages – leading them to describe their early sound today as “bestial blackened metal”. 1995 debut album Through the Impure Veil of Dawn contains more recognisable black metal traits, with frantic riffing and more epic song structures evident (not to mention Darkthrone shirts and corpsepaint in the band photos) though the deep growls largely remain.

The black metal component of the band would really push itself to the fore on Wings of the Nightstorm from 1997 however, with fierce yet melodic riffing, clean guitar parts and occasional synth, offering a lo-fi but evocative assault. The band would continue in this vein while also drawing from death metal and even heavy metal inspirations on Weeping Holocaust Tears in 2003 and Daemonspawn in 2007, as well as several EPs and a 2011 split with Sigh, Taake, The Meads of Asphodel and Evo/Algy. Founder, vocalist, guitarist, and keyboard player Paul Carter has also been active behind the scenes, not least through Arcane Promotions, which has organised many significant black metal related shows in the UK.

Hecate Enthroned – or Daemonum as they were originally known from 1993 to 1995 – were a much more resolutely black metal affair from the start, utilising corpsepaint, keyboards, Satanic and nature-inspired lyrics and a heavy degree of mystique and atmosphere. As well as playing shows as Daemonum, the band would also release a 1995 demo entitled Dreams to Mourn, a raw, aggressive, and sinister slice of Satanic black metal with touches of death metal and death-doom thrown in the mix, the group adopting the moniker Hecate Enthroned soon after.

Under this name, they would record the classic 1995 demo cassette An Ode for a Haunted Wood, this being remastered, partially re-recorded, and rereleased on Blackened the following year as the Upon Promeathean Shores (Unscriptured Waters) CD. The songs on this opus and the two albums that followed – 1997’s The Slaughter of Innocence, a Requiem for the Mighty and Dark Requiems… and Unsilent Massacre – offer evocative and epic black metal with a mix of blasting sections and slower paced passages, heavy use of synth and high-pitched screamed vocals. 1999 would see the band experimenting with death metal on the Kings of Chaos album, but they returned to the black metal genre with 2004’s Redimus album, and have continued to walk this path until today.

Final among the significant early UK bands are Ewigkeit and Old Forest, both studio-only projects created by one James Fogarty (sometimes known as Mr. Fog or Kobold) who also cofounded The Meads of Asphodel). Formed in 1994, Ewigkeit was a solo project and would change style dramatically during the course of its life – ultimately leaving black metal territories – but the prolific output from 1994 to 1999 would share a fair amount of common ground with Cradle of Filth and Hecate Enthroned, thanks to a combination of Scandinavian black metal influences, heavy synth use and slower death-doom dramatics, not to mention similar forest/witchcraft aesthetics, though these were ultimately replaced by a more celestial theme. Old Forest were formed in 1998 and lean even closer to a cold Norse template musically but (as the name suggests) have a definite nature/forest aesthetic, once again using synths, emotive riffing and some doomy overtones to great and atmospheric effect.

“I came upon black metal via the famous Kerrang! article,” Fogarty explains. “When I discovered Burzum was done by one guy, I wanted to know how I could make music by myself too, as there were literally no musicians wanting to play this stuff. I was forced to do it the cheapest way I possibly could, which was to get a cheap keyboard with which you could manually programme drums and keys and play along to it with live guitar whilst recording vocals into a very poor/cheap 1970s microphone and recording onto a borrowed tape deck. Whereas many bands did their best stuff early on, I think Ewigkeit was learning on the hoof, so actually only really got going from the second album, Starscape, which was symphonic black metal and far more musically intricate. The sound is raw as fuck, but in terms of the music, I am very pleased with it and there were very few releases around this time that were space-themed black metal.”

“Old Forest was more typical of black metal,” he adds, “whereas Ewigkeit was, and always has been, a lot more experimental after my initial start. The name Old Forest, although taken from Tolkien, was more inspired by the dense forest that once covered [the county of] Sussex; the Weald … In terms of the inspiration for the whole band, it was twofold; the black metal of the era (non-commercial and underground, with no aspirations of success) and also the media’s portrayal of the black metal circle at the time – you can read this as ‘Kerrang!’s hyperbolic portrayal of the Norwegian scene’. The latter element shouldn’t be underestimated, in terms of its importance to every black metal band formed after ‘92.”

To some degree, it can be said that Cradle, Hecate, Ewigkeit and Old Forest offered the first glimpses of a recognisable UKBM sound, and it’s notable that all bands demonstrated influence by the much-celebrated death-doom subgenre that had emerged just a few years earlier thanks to native heroes Paradise Lost, Anathema and My Dying Bride.

Unfortunately, a handful of bands does not make a scene, and few metal fans and practitioners – in part due to the lingering success of the English grind and death metal scene – converted to the black metal cause at this time. The result was that the UK simply did not have the sort of social and artistic crossovers seen in countries like Norway, Sweden or Greece during the 1990s. James’ own experience underlines this and he raises an interesting point about the metal media in England, which it must be said, was highly resistant to black metal during this decade, Terrorizer excluded.

“It was very isolated. I had like four or five friends who were into black metal from the same city,” he recalls. “There just wasn’t anyone else who knew this stuff. You might occasionally see someone wearing a Cradle of Filth shirt, but they didn’t know anything about black metal if you spoke to them. So you basically had to get writing to people, tape trading, buying zines from flyers you received. That whole tape trading scene was still very much thriving until the late 90s. I’d say that Europe was definitely way ahead – the UK music press were so used to dictating to Europe what was new and exciting that it had become a one-way conversation, and they were blind-sided by the fact that black metal was more than just some crazy kids burning churches in Norway. I think bands like Emperor and Cradle of Filth playing shithole venues circa ‘93 and then transferring to the London Astoria/London Astoria 2 circa ‘97 is a good indication of when the whole scene started to grow in the UK. But as far as actual UK bands, they were still far and few between. You’d have a handful in London playing that scene, and perhaps a few further north, but there was little support for homegrown bands, aside from Cradle of Filth. And to be fair, it’s because they were doing it better than most – even if I didn’t personally like what they did/do.”

“The UK never has, and never will compare to the more solidified scenes in the rest of Europe/the world, and that’s a lot of scenes, Finnish, German, Polish, Norwegian etc.” opined Metatron of The Meads of Asphodel to me in 2007, a time when hope had seemingly all but dried up. “We Brits tend to produce great black metal bands once every ten years, a few good ones every couple of years, and lots of one-man bands regurgitating Darkthrone riffs under the banners of ‘necro’ and ‘true black metal’. The UK could put on an all-dayer with a good line-up but that would be pushing it, the other countries could put on a three-day festival and have decent bands on all day for three days. Eccentricity and a lone individuality, that is the UK’s only merits. Musically, this seclusion of styles makes any cohesion impossible.”

Harsh words, but not unfair at that time. Speaking frankly, the late 1990s to the mid/late-2000s were a disappointing time for devotees in the UK. Not as a fan wanting to see bands, mind you – England, and especially London, has always been one of the best locations in the world for live metal shows, and this era was no different, the capital being treated to regular appearances by international bands, including such stellar and diverse names as Dissection, Emperor, Sigh, Moonspell, Watain, Marduk, Old Man’s Child, Blacklodge, Demoncy, Rotting Christ, Celtic Frost, Mayhem, Gorgoroth, Impaled Nazarene, Limbonic Art, Aborym, Negură Bunget, Shining, Enslaved, Antaeus, Enthroned, Arcturus, Ved Buens Ende, Dødheimsgard, Horna, Ondskapt, Immortal and Ancient Rites, to name but a few.

But homegrown talent and the foundations of a cohesive movement were notable by their absence. Some strong bands surfaced during this time, including Archaicus, Reign of Erebus, Necro Ritual, Heathen Deity, Skaldic Curse, Niroth and Instinct (though it should be added that some of these only created their best works later), but they were few and far between. More worryingly, the UK seemed to lack, even shun, the camaraderie and spirit of creativity and collaboration present in other countries. One review of the first issue of my fanzine Crypt, noted that every UK black metal band interviewed considered themselves to be entirely separate from the rest of the scene in their homeland. It was a telling point, and a curious degree of misplaced antagonism and unfounded elitism became the norm, with native musicians, fans, and promoters seemingly suspicious of their peers, often trying to outdo each other on blackmetal.co.uk – one of the first popular black metal forums. Many people seemed genuinely wary of releasing music for fear of being shot down, perhaps a reflection of collective insecurity owing to the lack of achievement from the British scene until that point.

“Those early days were tough,” recalls Azrael, who has contributed to many UKBM bands such as Heathen Deity, Atra Mors and Thy Dying Light. “It was hard to get any shows as there wasn’t really anywhere for black metal bands to play. Not at the level we were at during that time anyway. Obviously, we got the odd show here and there, but they were few and far between. There was no real solidarity between bands or venues at the time. Not like there is today. You were out there on your own.”

“It was an odd time in some respects,” agrees The Watcher, who co-founded such bands as Skaldic Curse, Fen and Fellwarden. “Certainly, within the underground, it felt like the mid-2000s in the UK were something of a ‘no-man’s land’. The main acts established within the 90s were of course all present and correct to various degrees of success, but there was no real sense of unity, no perception of a focussed, recognised ‘scene’, for want of a better word. That’s not to say that newer acts weren’t forming or gaining recognition, but these tended to be more studio-based, adhering to almost defiant perspectives of individualism, eccentricity, or good old-fashioned isolationism. It goes without saying that though there was undeniable quality running through the material that did emanate from these shores, any sense of mutual support and celebration across these acts felt to be in short supply. The searchlight pointed overseas, scanning north and east for the next big thing. There was no real feeling of support or pride for UK bands within the UK at that point – indeed, far from the pride we see many here take in the strength of the scene these days, there was a palpable sense of disappointment, self-flagellating shame or indeed, outright hostility adopted towards UK offerings. It felt as if there was some sort of inferiority complex at work.

Black Metal: Evolution of the Cult by Dayal Patterson is published by Cult Never Dies