Two of the biggest prizes in literature were shared this year – in neither instance uncontroversially. Bernardine Evaristo shared the Booker with Margaret Atwood, only to be dismissed and erased by the BBC as "another author" beside her more famous co-recipient. Meanwhile, after 2018’s cancellation when three jurors quit over allegations of sexual-misconduct, the Nobel Prize in Literature split the award between Polish author Olga Tokarczuk and Peter Handke, a writer notorious for his outspoken support of Slobodan Milošević.

The Quietus has never been one to avoid controversy, however. In fact, we reckon we can go one better than that. Share the book of the year gong between just two writers? Stuff that. How about thirty?

The following list, voted for by Quietus editors and regular Tome on the Range contributors and bodged together with extreme prejudice and no small amount of caprice by Robert Barry, is split into two halves: fiction and non-fiction. As the Tory’s recent election campaign ably demonstrated, the line between the two may be shakier, more permeable than ever, but you still need to know what floor to get out of the lift in Foyles at, so…

Fiction

Kevin Barry, Night Boat To Tangier (Canongate Books)

Night Boat to Tangier is a hymn to Spain and Cork and SE Hinton and the loneliness of men who like Hank Williams and much more. Kevin Barry’s writing here has the brisk allusive power of those early Michael Ondaatje books like Coming Through Slaughter. There’s a similar pacing, lines as loaded and hidden as a landmine that call a sudden halting and then impact in the head with their dizzying fragments. You feel fragged. You are made to feel the pain of the pair, to empathize sometimes against your better judgement, just as in real life, and yet laugh too at their lunacy, their sad predicament. As with encounters with the staggeringly inebriated strangers you escape, enervated, a tad fried, and with a sigh of relief that theirs is not your life. Read the full review by John Quin

Ray Celestin, The Mobster’s Lament (Mantle)

The third part of The City Blues Quartet is a superb noir murder mystery set in New York in 1947. Almost like a British James Ellroy, Celestin blends real history with invented drama – Louis Armstrong is not just part of the series’ musical backdrop but a recurring character in the narratives – and the intricate construction sees different characters converging on the truth, each having picked up different pieces of the puzzle. Throughout the series the writing has been an unalloyed joy – the depth of research worn lightly; the details rich and evocative without ever weighing down the prose – but Celestin reaches new heights here. Angus Batey

Ted Chiang, Exhalation: Stories (Knopf)

Peter Watts dreamed of disconcerting transhuman futures. Jeff VanDermeer envisioned an alien eco apocalypse. Even the ever-optimistic Star Trek was reborn in grit. In contrast to the past two decades of dark and cynical science fiction, Ted Chiang’s cautious hope is an aberration. His second collection of short stories Exhalation, much like 2002’s Stories of Your Life and Others, deals with intricate techno-ethical questions about determinism, artificial intelligence, and time travel, among others. But instead of fear, he finds the promise of humanity in them. In place of technological apathy, he discovers a lyrical soul. A wondrous hammer to break all the black mirrors out there. Antonio Poscic

Taylor Jenkins Reid, Daisy Jones & The Six (Ballantine)

You might be able to guess what happens when young Daisy Jones, a Sunset Strip devotee, gets paired with up-and-coming rock band The Six to make a record in the early 70s, but the story goes well beyond that. Taylor Jenkins Reid weaves a magic that makes this tale more enthralling than any real-life band biography, drawing from sources of the time a la Fleetwood Mac, all while sustaining a truthfulness to their tone. Reid has us wanting, no, longing to hear the records whose creation she describes, wishing we could hold the 12” cover art in our hands to pour over those magic photos, knowing these would all hit us in just the right way, such has she set the scene. A perfect rock n roll dream. Aug Stone

David Keenan, For the Good Times (Faber)

My gold standard for an incredible book is one that seeps into your subconscious, and reading For The Good Times over two nights gave me one horrific nightmare about being captured and tortured by IRA men, and a second about having an orgy with them. Although it’s set against the background of the Troubles, David Keenan’s second novel isn’t a book about the conflict in Northern Ireland per se. Instead, it’s an honest – often brutally so – examination of masculinity and the allure of violence, and how chaos can intertwine with the mundane. Luke Turner

Deborah Levy, The Man Who Saw Everything (Hamish Hamilton)

Deborah Levy continues to stake her claim to be one of our greatest living writers of fiction with this time-shifting, magical book. Interestingly, the cold war setting means that at times it reads like a fresh take on a spy novel – it’s certainly a pacey and accessible read. What’s more, within the themes of unreliable memory and how our lives decay, for once it’s a novel which deals with complex and fluid sexuality in a nuanced and realistic way. Luke Turner

Adam Nevill, The Reddening (Ritual Limited)

The unearthing of an important prehistoric archaeological find in Brickburgh’s caves brings uneasy revelations regarding mankind’s violent and cannibalistic past.… In drawing a connecting line between the darkness we inhabited in our ancient past, and the tense times we currently occupy, The Reddening strikes a resonating note that reverberates from the dawn of our prehistory and continues to echo threateningly in our present era.

In a field where much of the best writing takes place in the short-story format, Nevill is one of the best long-form authors the genre has. Whilst there may be other 2019 horror books I’ve not yet read (such as Catriona Ward’s Little Eve, which scooped the Best Horror Novel category at the 2019 British Fantasy Awards, or Chuck Wendig’s intriguingly premised 800-page doorstop of a book, The Wanderers), The Reddening sets the bar for literary horror especially high, even by Nevill’s own standards. Read the full feature on Adam Nevill and The Reddening by Sean Kitching.

Max Porter, Lanny (Faber)

Beyond all other things, Max Porter is an author who writes about love. In Grief Is A Thing With Feathers he offered a portrait of a family coping with a situation and a loss that for most of us remains distant, only glimpsed in the bleakest, darkest point of our fearful imaginations. Lanny contemplates a similarly diabolical domestic occurrence: a child going missing. Lanny is a deeply moving, folkloric odyssey that blends ancient magic with modern life, the ordinary and the miraculous, and most importantly our innately human hopes with our deepest fears. Read the full review by Hannah Clark.

Miriam Toews, Women Talking (Faber)

Women Talking is a rich and strange creation, an imagined dispatch from the historical spaces which we cannot enter, cannot reach, which went unrecorded and ignored. It is a sort of forged historical document, deeply desired by those who refuse to believe that our foremothers were merely meek and mild. The Molotschnan women wrangling “Menno Simons’ fevered vision” and “Peters’ angry interpretation” become all women, to whom this novel is, in the words of Toews’s acknowledgements, a missive of “love and solidarity”. All stories like it – of female resistance, quiet insurrection, bravery – whether history or fiction, are to us what facts are to the colony members: “gifts, samizdat, currency, they are the Eucharist, blood, forbidden”. With each offering of precedent, we are emboldened in our aims, and in our acts of imagination. Read the full review by Stephanie Sy-Quia.

Colson Whitehead, The Nickel Boys (Fleet)

As politicians all over the world stoke prejudice to win votes, Whitehead’s brutal follow up to The Underground Railroad lays bare the systematic racism and corruption entrenched in American society. Based on a real reform school, this fictionalised version is a gripping, powerful read of injustice and cruelty. Pete Redrup

Don Winslow, The Border (William Morrow)

Winslow continues to hone his talent for demanding cerebral engagement of his readers while simultaneously forcing the adrenal glands to work overtime as his narratives gain terminal velocity. With unflinching realism, The Border brings his drug war saga to an inevitably frayed and unresolved conclusion. Here, the War on Drugs is presented as a kind of Greek tragedy. But whereas the ancient Greeks saw humans as the playthings of the Gods, in Winslow’s bloody deserts and urban warzones, humans are forever abandoned to their own greed, desperation and folly. A challenging yet essential read. Chris Brownsword

Olga Tokarczuk, Drive Your Plow Over The Bones Of The Dead (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

In a typically astounding passage, Polish author Olga Tokarczuk’s protagonist Janina expands on her theory about why men develop "testosterone autism" with age. She claims it’s a condition that makes them taciturn and appear lost in contemplation, while fostering an interest in tools, machinery, the Second World War and biographies of politicians and villains, adding: "His capacity to read novels almost entirely vanishes." I groaned with self-recognition at this paragraph. When I was 18 I read three novels a week. I’m now lucky if I read that many in a year, reasoning: how likely am I to read another White Hotel or White Noise. But I persevere in the vain hope I’ll stumble across something as good as Drive Your Plow Over The Bones Of The Dead. And sometimes I do.

John Doran

Non-Fiction

Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, & Nancy Fraser, Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto (Verso)

“Feminism must be anticapitalist, eco-socialist and antiracist.” Collecting the ideas and principles of the eponymous grassroots movement, Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto is a crucial formulation of an inclusive, transformative, and global social shift. While the book draws and aggregates ideas from various variants of feminism, it is the way they are framed within intersectional contexts which makes it so successful. The manifesto conceives feminism not only for affluent neo-liberals, but for those at the bottom of capitalist hierarchies. Not just for whites, but for all races. Feminism inclusive of trans* people and for the collective, not the select few. Antonio Poscic

John Carreyrou, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (Picador)

The veneration of tech firms created by 20-something self-promoters with CVs that inevitably include a deliberately incomplete education is a mystery for the ages, and Carreyrou explains with aplomb how one of these individuals – Elizabeth Holmes, founder of blood-testing company Theranos – stepped over the mark from "chutzpah" to "crime". There will be more stories like this to come: let’s hope they all find someone as skilled, diligent and accomplished to tell them.Angus Batey

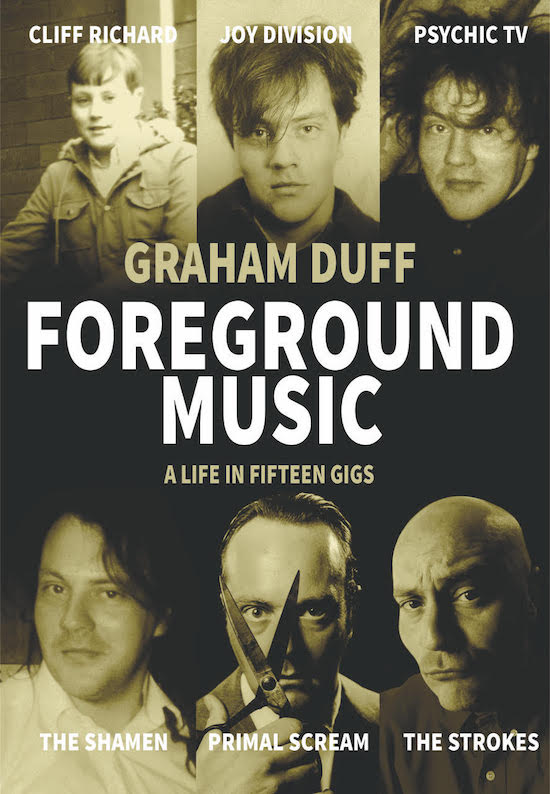

Graham Duff, Foreground Music (Strange Attractor)

Foreground Music is a delight. Not just for music lovers, who will find themselves resonating with much within every page, every paragraph. But also for anyone whose passion for something ignites the desire to consume and experience everything about it, and in doing so, enrich one’s own life and the lives of others through the sharing of the subject’s vitality. There’s something wonderful about the way someone who is so knowledgeable and effusive about a subject dear to them – so much so that it seems a component of their very being – can inspire another to want to come into contact with this curiosity themselves, despite not previously possessing the slightest bit of interest.

What I’m trying to say is that as an American only familiar with, and for decades now confused by the success of, ‘Ebeneezer Goode’, Foreground Music had me chomping at the bit to explore the early records of The Shamen. Read the full review by Aug Stone

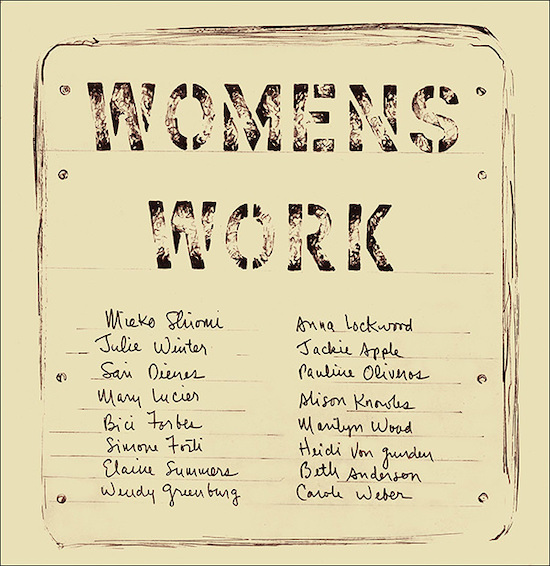

Alison Knowles, Annea Lockwood (Ed.), Womens Work (Primary Information)

Originally published as a two-issue magazine in 1975 and 1978, Womens Work is the sort of publication that, for better or worse, today seems as relevant and alive as 40 years ago, and not a mere archival reissue. The various graphical and text scores, which Fluxus co-founder Alison Knowles and composer Annea Lockwood collected from 25 women composers—featuring Pauline Oliveros, Christina Kubisch, and the editors themselves, among others—are all vibrant pieces of art, inviting participation and delineating of the creativity and struggles of women in music. The physical properties were an important aspect of the magazine and Primary Information’s reissue transcribes them faithfully using off-white paper and brown inks. With such care, they gifted a new generation the chance to revisit these important artefacts and carry them into the future. Antonio Poscic

Natasha Lennard, Being Numerous: Essays on the Non-Fascist Life (Verso)

The most important takeaway from this series of essays, some of them drawn from her contributions to publications such as The Nation and The New Inquiry over the past couple of years, is that Lennard argues persuasively and cannily for the use of violence in protest. At times she does this by referring to figures within the mainstream liberal’s comfort zone: Dr. King is quoted early on, to ease us into things (“[We are dealing with] the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order‘ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”). Read the full review by Stephanie Sy-Quia.

Nathalie Olah, Steal As Much As You Can (Repeater)

Writing this on the day when, after a decade under the thumb of a bunch of old Etonians, the British public have elected a Tory government with a huge majority, Quietus contributor Nathalie Olah’s first book feels like an essential read. So often it feels that in all the contemporary conversations about diversity we’re rightly having at the moment class is the last thing to be mentioned, when it arguably should be the first. An exploration of the disappointment of the Blair years and subsequent toffication of culture, Steal As Much As You Can is a fierce argument for new networks, collective action, and most of all the abolition of the private school system. Luke Turner

Ian Penman, It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track (Fitzcarraldo)

A gathering of work previously published by City Journal and London Review of Books, Penman’s subjects are a canny mixture of legend (James Brown, Charlie Parker, Frank Sinatra, Elvis, Prince), fascinating outlier (John Fahey, Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen), and movement (an unflinching unpicking of the continuing Mod revival). … It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track is a stirring reminder that heading home – wherever and whatever that might be – does not have to be an escape from the world but a retreat to a position from where one might view the world, and your place in it, anew. Penman’s worldview is, as it ever was, an abundantly humanist one and this peerless collection of work hits you where you live. Read the full review by Gary Kaill

Joe Thompson, Sleevenotes (Pomona)

At some point while reading Sleevenotes it becomes clear that it was much more than just a wise-cracking, experimentally punctuated, string of anecdotes about squat gigs in Belgium with improbably named noise rock bands and blocked studio toilets in Camberwell. This book should in fact be regarded as core curriculum reading for those just embarking on the path of rock music today, and is essential nourishment for those who have existential concerns about the point or the viability of doing such a thing in 2019. And once you acclimatise to Joe Thompson’s easy-going, autodidact style you will, I guarantee it, find yourself punching the air (when you aren’t nodding furiously in agreement). Read the full review by John Doran (plus an interview with the author and an extract from the book)

Jia Tolentino, Trick Mirror (Penguin Random House)

Subtitled ‘Reflections on Self-Delusion’, Jia Tolentino’s terrific selection of essays gleans much-needed sense out of the daily distortions and conflicted opinion that emanate from our mass media outlets. This assault, as Tolentino neatly has it, is “blitzing our frayed neurons in huge waves of information that pummel us”. Often the sparring dialectic in evidence here pairs Tolentino’s current self in a duel with her youthful (mis)understandings; experience leads to a rigorously bracing self-interrogation.

Tolentino’s mental cleansing acts like a literary disinfectant; the verbal equivalent of a water cannon fired at the fetid walls of the foul stable that is Trump’s America. Short of wiring the entire body politic to ECG machines it is hard to imagine, after reading Tolentino’s diagnoses, a more accurate and prescient way of taking her nation’s pulse. Read the full review by John Quin

Luke Turner, Out Of The Woods (W&N)

A beautifully written, open and honest account of growing up in a religious family as someone whose sexuality and lifestyle are at odds with how he has been told to be by both society and the church. Finding peace and something close to redemption in the woods, it’s impossible not to be moved by Luke’s realisation of how he needed to learn to overcome his personal demons. Pete Redrup

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (Profile)

I usually despise the label of “books that everyone should read”, but Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism fits neatly into this category. With a technological revolution that has, as always, caught societies at large unprepared, it becomes crucial to understand how our new normal of daily interactions with the digital shapes our real world. Here, unscrupulous techno-capitalist actors manipulate our naiveté to destroy and reconstruct the fabric of society, one bit at a time. While sometimes dense due to the nature of the subject, the book as a whole reads like a thriller: exhilarating and frightening. Antonio Poscic

Paul Gill & Ste Pickford (Editors), Freaky Dancing: The Complete Collection (tQLC)

I’m glad that ageing ravers now have this psychedelic time capsule of art from the near past but I also hope some young people read it and do whatever the 2019 equivalent is. I hate the way that large commercial interests have warped the ecosystem of even leftfield electronic dance music, insinuating that it’s now the preserve of well-off people. The big, monopolistic platforms present an unhelpful image of who the modern clubber is by catering primarily to people to whom buying a fitted, designer black T-shirt for £278 or spending 48 hours at the Berghain on a whim is no big thing. For most of us who still go out, clubbing is something that’s local and styled by TK Maxx. So if any young person is sat in a bedsit in Cheetham Hill, looking at Boiler Room on YouTube and thinking, ‘Fuck it. I can’t afford all this’ – rather than finding it aspirational – then something’s gone wrong somewhere. I hope Freaky Dancing remains a clarion call: don’t be a passive observer of other people’s art when you can produce your own. It’s your preserve, not just ‘theirs’. Own it.

John Doran

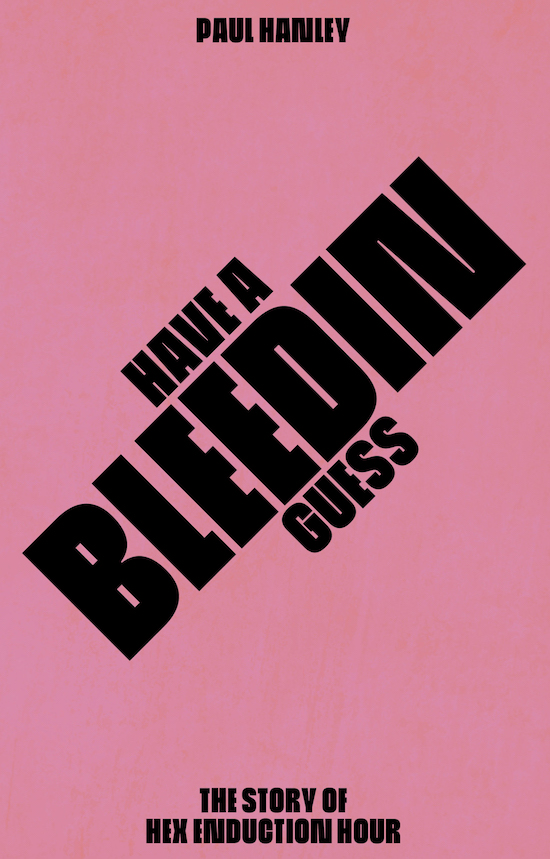

Paul Hanley, Have A Bleedin Guess: The Story Of Hex Enduction Hour (Route)

This is really top notch stuff. It’s a book written squarely for Fall fans (something I applaud as I have very little interest in slogging through loads of “always the same/ always different” style received wisdom, although there is some necessary discussion of the grandmother/bongos jurisprudence), so is full of very detailed factual information (including kit lists) while never at the expense of being really well written. It’s sanguine, droll and even-handed – respectful to Smith while calling out his poor behaviour where necessary. It corrects many of MES’s fanciful tall stories (some ably propagated by me to be honest) without attacking the core mystique of the album at the centre of the text: Hex Enduction Hour. Makes a superb companion piece to his brother Steve Hanley’s The Big Midweek: Life Inside The Fall for a rounded view of what it was like being in the greatest rhythm section of the world’s greatest band while they recorded their greatest album.

John Doran