Mat Colegate writes:

It’s been a while and, yes, we have much to talk about. The world these days moves in fast and strange ways and it seems that life-altering, future scarring news is round every corner. Doubtless, in the month since we last met your existence has slipped into new modes and directions with every shed skin cell, just as mine has. However, in introduction to this month’s column, I have only one thing to say…

Look what I got for my birthday…

Now THAT, motherfuckers, is what pumps my dice.

On with the reviews.

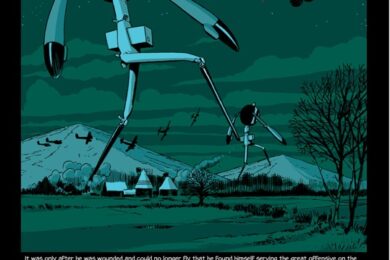

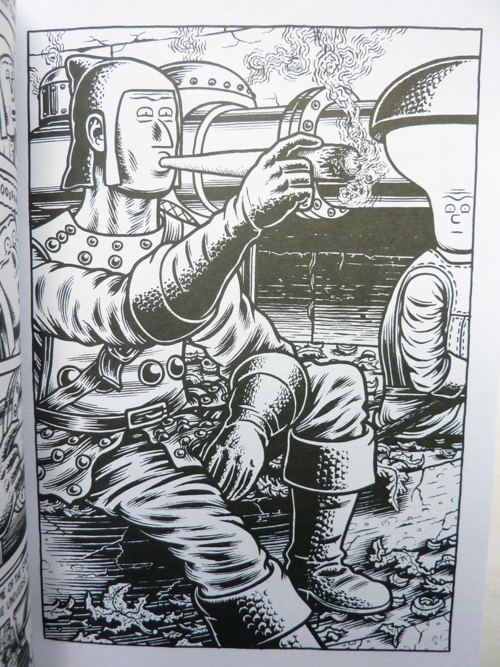

Dal Tokyo

(Gary Panter, pub. Fantagraphics)

I wish you could hold this thing in your hands, I really do. (By all means go into your local comic shop and paw away at it, just mind you don’t contribute to any page warping. That would be, as my hip-with-the-kids ex-headmaster used to say, Supremely Uncool). A collection of Gary Panter’s long running Dal Tokyo strip has been long overdue and having Fantagraphics release this gorgeous hardback – one strip per page, beautifully reproduced and with the inks practically weighing down the paper – is a total treat. Panter is probably one of the single most influential underground American cartoonists of all time, a kind of Ramones to Robert Crumb’s Jefferson Airplane, which makes his relative unknown status a bit baffling. A cartoonists’ cartoonist, maybe? Whatever, you don’t need to know one end of a white board from another to know that Dal Tokyo is The Heavy Special. Dal Tokyo loosely tells a series of interconnected stories all set in Panter’s imagined future metropolis, a futuristic cross-pollination of Dallas and Tokyo, but, obviously, on Mars, that features an array of maddeningly named characters going about an array of maddening business.

Story-telling wise, I would say it’s closest antecedents would be the more sci-fi scuffed William Burroughs novels such as Cities of the Red Night or The Wild Boys, but with a more deliberately pointillistic, scattershot approach. Yep, even more scattershot than old Bill, who knew a fair amount about scattering his shots around, am I right, Joan? This seeming lack of narrative tension initially had me writing Panter off as some kind of beatnik Psammead. A wish granter to cartoonists who wanted to shed a lot of ink about nothing whilst coming out coated in the fresh scent of the underground, but closer attention (and this book demands close attention) reveals Panter is a serious, serious dude, and me as a fucking idiot for not getting it sooner. God, the feel of this stuff. What on first appearance appears merely ugly (or naïve, if you’re walking the charity mile), on repeat exposure reveals a host of complexities and delights. The man’s inks are practically sentient, devouring white space like it was candy floss as his crude likenesses become imbued with a very deliberate purpose, that of guiding the reader through Panter’s personal inferno: the urban Twentieth Century. Get this book, smoke Marlboro reds while you read and grip yourself a brew, you’ll come out warping.

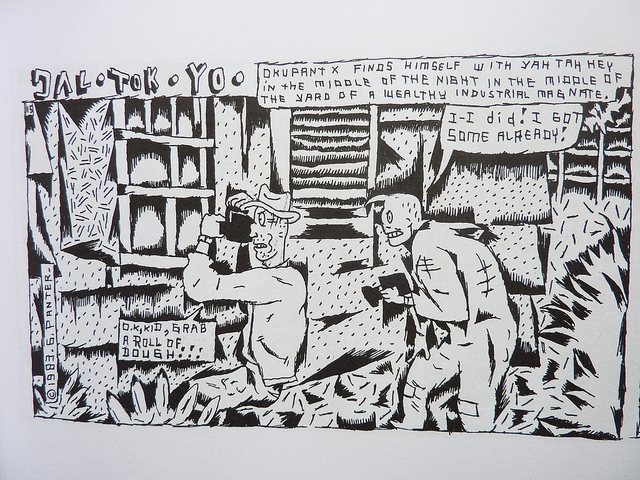

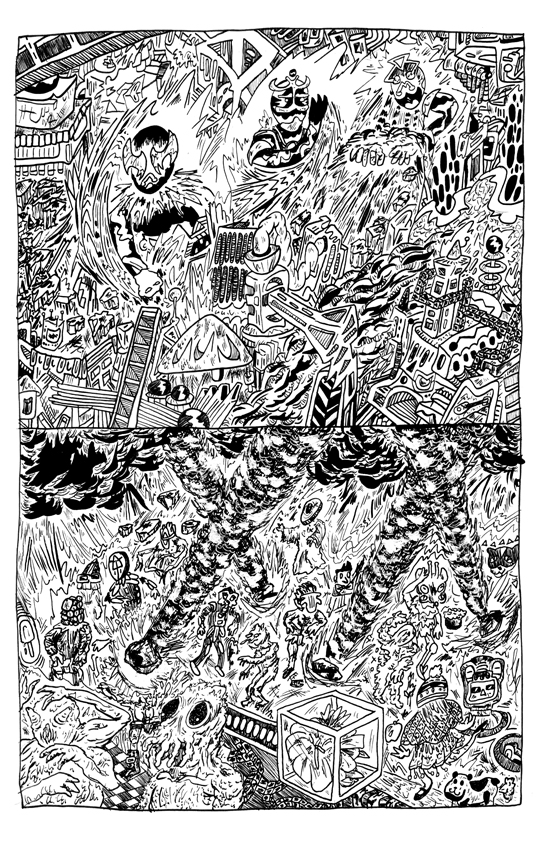

Suspect Device #2

(Various: edited by Josh Bayer, pub. I am War)

Bowman 2016

(Pat Aulisio, pub. Hic and Hoc Publications)

Josh Bayer and Pat Aulisio are two good-drawing folk who I would say have hit a direct line from Panter’s brand of the inspired and the slap-shot. Those of you who have memories may recall my review of Bayer’s Raw Power in the last column, and Suspect Device #2 confirms my hunch that this guy is worth sticking a few sheckles on. An anthology featuring some serious (and to me previously unknown) talent, Suspect Device #2 (SD2, as we’re going to call it from now on) starts with a very simple premise, take a couple of panels from some old comics (Garfield and Nancy comics in this case) as your beginning and end point and find the weirdest, grossest way to get from A to B. The results are astonishing, and the anthology ends up reading less as a collection of separate work and more as the home-sick-from-the–factory fever dream of a 60-year-old, sexual frustrate resident of Shitsville, North Carolina with the TV on too loud in the background. If that sounds like a recommendation to you (and if it doesn’t, quite frankly you’re not going to find any space in my Filofax) then I would hunt this sick puppy down. One of the artists in SD2 who sticks out that little bit more is Pat Aulisio, making this the perfect opportunity to recommend his scratched and slurry Bowman 2016. If the idea of an ultra-violent, surrealistic sequel to 2001: A Space Odyssey drawn by a diseased child holds any appeal then pick this fellow up. Like Bayer, Aulisio’s drawing is a wonderfully sloppy and skittering thing which masks some proper chops. Bowman reads like a dream, not a particularly nice dream mind you, more the sort that makes you fight invisible bats and scream your lungs out at the moment of waking, but it’s good to swing by that neighbourhood on occasion, right? Right.

Dungeon Quest Book Three

(Joe Daly, pub. Fantagraphics)

On to one of my very favourite things in the world. The third volume in Joe Daly’s Role Playing Game-inspired fantasy series is out and it is a solid gas. Following the adventures of the unfeasibly craniumed Millennium Boy and his fellow questers, Steve, Lash Penis and Nerdgirl as they seek to unite the separate pieces of the Atlantean Resonator Guitar. Now, you’re reading a comics column so I’d bet that the concept of RPGs is not completely unfamiliar to you, am I right? You ever rolled a D20, tough guy? Have ya? Huh? Yeah, I bet you have. Bet you enjoyed it too. Well, if you’ve ever spent any time at all fussing about what your armour class might be and querying your mage’s alignment then Dungeon Quest is a must read, packing in gorgeously realised and detailed drug experiences (the characters are constantly getting boxed on preposterous weed), oodles of stats (everyone loves stats) and more anarchic humour than you can shake a spiked stick at (that stick gives you plus 6 damage and plus 2 defence, by the way). Needless to say, this is not your straight Tolkien rip-off. Dear J.R.R. certainly never had one of his characters wank off a gnome, did he? Indeed Dungeon Quest’s good natured, silly humour gives it much of its character and combines with Daly’s beautiful Charles Burns-esque artwork to make the book much more than the sum of its parts. It feels like a real labour of love and when you read it you’ll see why. Nerdgasm guaranteed. I’m in love with this comic.

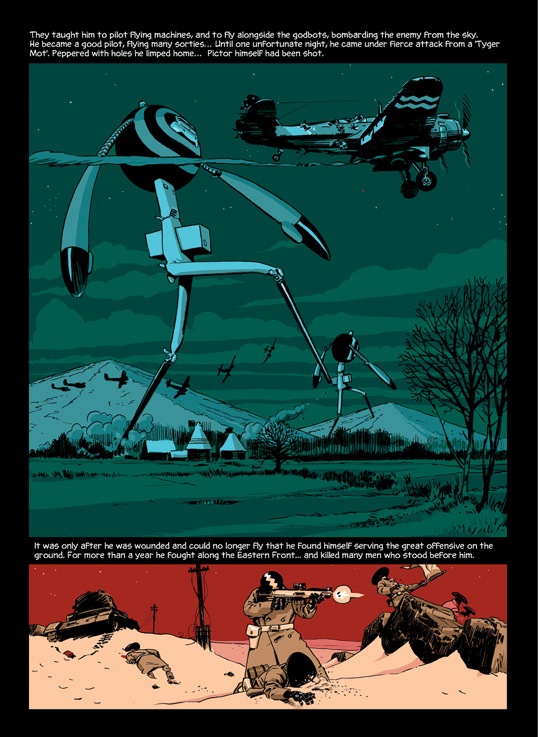

No Man’s Land

(Blexbolex, pub. Nobrow)

So this one just about creeps on to the comics page by virtue of, well, where the hell else are you going to put it? This is a beautifully illustrated picture book by French artist Blexbolex (that’s a snappy name, innit? Say it out loud. Satisfying, like throwing a lit cigarette into a puddle). Taking the format of a child’s picture book – one illustration per page, text at the bottom – to tell a warped and at times confusing tale of espionage, war and multiple identities. The influence of Burroughs is again in evidence here and teamed with Blexbolex’s gorgeous screen printed art forges a handsome, powerful tome. What really strikes about this one is the way the story rubs against the simple, almost childlike imagery. The frisson produced by putting an unmistakably warped and adult story in this particular format is something I hadn’t come across before and makes for fascinating reading. And, indeed, re-reading, as further delves had me encountering yet more depths and complexities. Nobrow’s customary attention to detail has ensured that this is one of the best looking books out there right now and that it will be riding high in a lot of end of the year lists. Totally deserved. Bravo, folks.

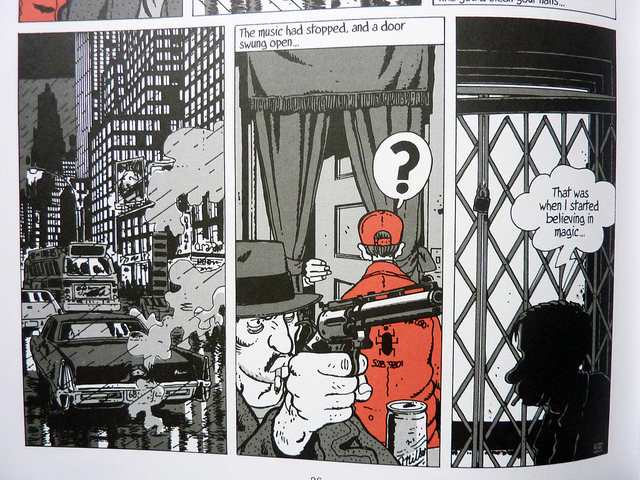

New York Mon Amour

(Jacques Tardi/Various, pub. Fantagraphics)

It’s taken a while for Jacques Tardi to gain the reputation he deserves on these shores, but it’s a reputation that’s going to get a whole lot meaner and more impressive if this book is as successful as it deserves to be. A collection of four of the French master cartoonist’s shorter, more noir influenced works, all set in and around the titular city, New York Mon Amour sees him on effortlessly brilliant form. The first story in particular, Cockroach Killer, written by Benjamin Legrand, is a masterpiece in miniature. A fully fleshed out conspiracy thriller with a disturbing, hallucinogenic punch. Using only black, white and red, Tardi illustrates a seedy, roach-infested New York that’s utterly plausible. You can practically smell the trash on the sidewalks as you follow the hapless narrator’s spiral into madness and murder. The other three stories are slighter (which after Cockroach Killer’s intensity comes as something of a relief), but serve to demonstrate the versatility of Tardi’s clear line influenced style and to demonstrate his impeccable storytelling. This is the one on the list where I would say, if you know anyone looking to take the plunge into comics, someone who’s interested in what the medium can do and the fascinating ways it can do it, then point them in this books’ direction. Or, better yet, buy it for them for their birthday. Sure, it’s not Batman Lego, but they’ll get a kick out of it for certain.

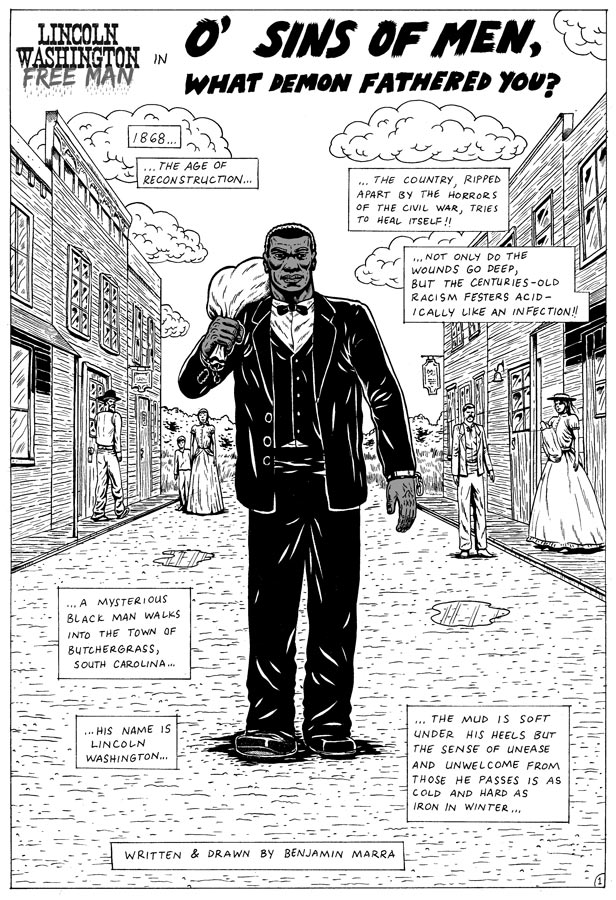

Lincoln Washington Free Man, issue 1

(Benjamin Marra, pub. Traditional Comics)

There is a lot of fuss being made about Benjamin Marra at the moment, and it’s pretty easy to see why. His crude, deliberate style has served to give the simple action comic a much needed kick in the vitals and his no-holds-barred approach to the violence has set many a gorehound tongue a’flapping, as well as earning him serious interview space with those perma-highbrowed folk at The Comics Journal. The story of a freed slave and his fight for the land entitled to him, Lincoln Washington is awash with hilariously cartoonish violence, sex aplenty and loads of glorious cussing. Time will tell whether Marra is remembered for more than just gory yucks, but in the meantime get with this hilariously cheap and nasty slice of good old fashioned entertainment and look forward to my interview with the man himself, coming soon.

Aug Stone writes:

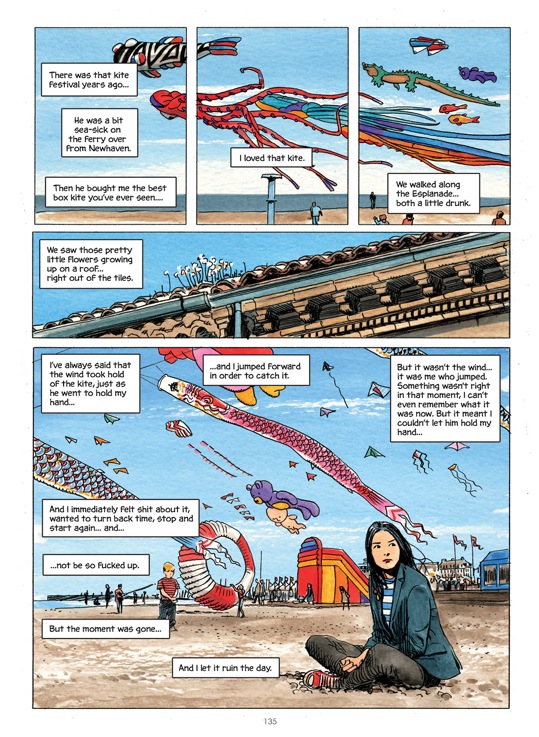

The Nao Of Brown

(Glyn Dillon, pub. SelfMadeHero)

I have yet to find a description of this story that can really sell it. Indeed, the blurb on the inside cover – “Nao Brown suffers from OCD… violent morbid obsessions… Working part-time in a designer toy shop, while struggling to get her own illustration career off the ground… searching for that elusive love…” – had me holding off reading it until the last possible moment. But within ten pages it was another story entirely. One marvels at the care and talent involved, the book coming alive with the fullness that the art portrays. Beautifully water coloured, Dillon perfectly captures nuances of expression. You can tell exactly what a character is feeling, however complex, simply by looking at what their eyes are doing. Time after time you catch yourself uttering ‘Oh!’ at some delightful aspect of the page. And the letter ‘O’ permeates this book, a symbol of Zen, painted by Buddhists throughout, the washing machine that plays such a pivotal role to the plot, the sound of Gregory Pope’s name, and an all ‘O’ mixtape, not to mention the OCD. If you live in North London, you’ll notice locations such as Big Red faithfully depicted. Of special note is the superbly drawn and beautifully told Japanese fairytale about a half-boy half-tree also searching for love that weaves in and out of the main story. Part of the “ichi” scene that Nao is a huge fan of, check out the site here. See if you can find the hidden songs by Nao’s old band, The Möbius Strip Club, on the second menu and guess who’s behind them. I must say I was charmed by The Nao Of Brown, the book far transcending any attempt to summarize its parts.

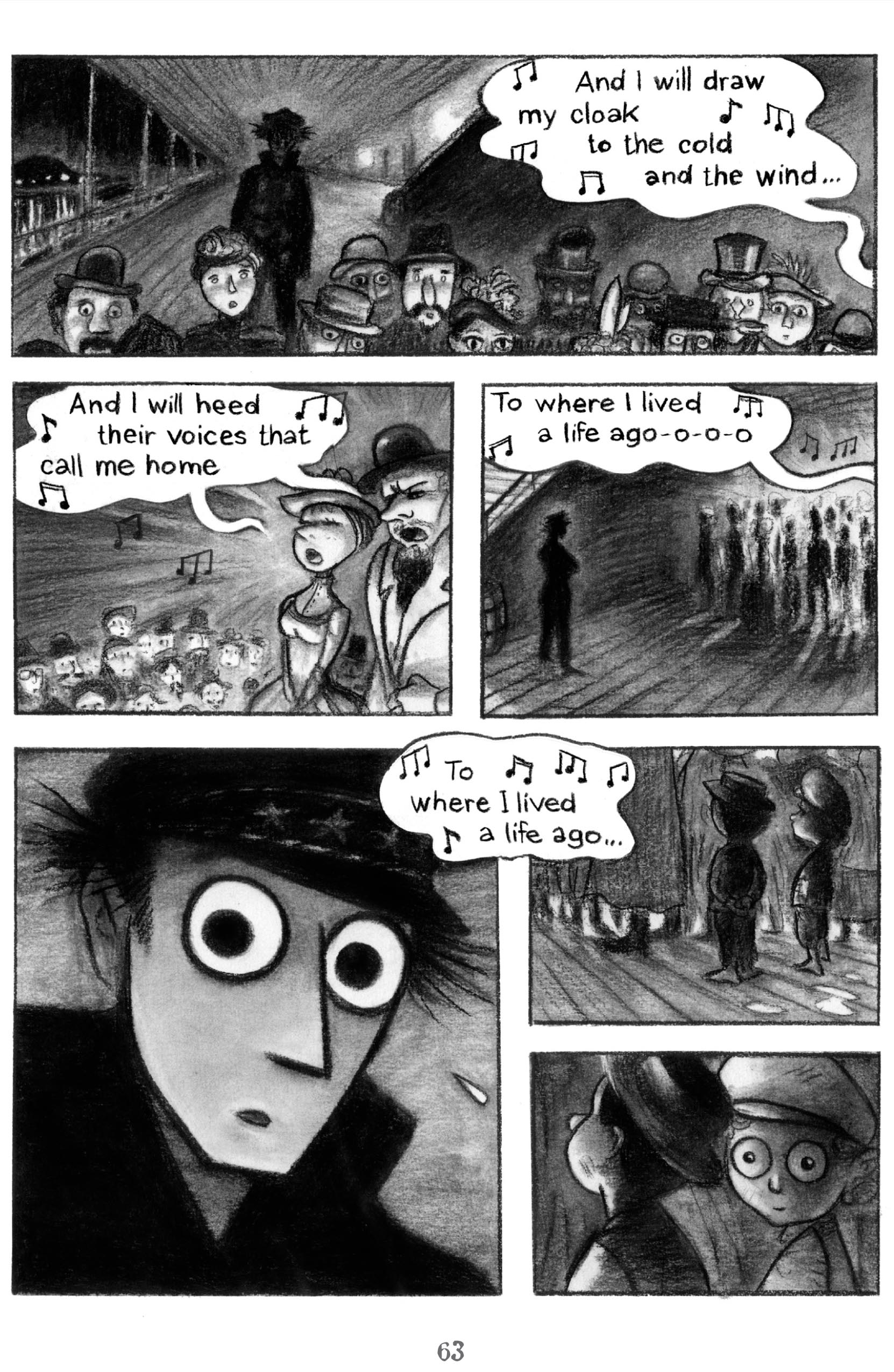

Sailor Twain, or The Mermaid In The Hudson

(Mark Siegel, pub. First Second)

This delightful book captivated me much like the mermaid’s song it sings of. Its lovely charcoals portray life on the Hudson River in the late 1880’s, rich with magic, immortal Trickster figures, sex-crazed Frenchmen, reclusive authors, and other intriguing individuals. In the centre of them all is Captain Twain, slowly losing his life’s moorings after rescuing a harpooned mermaid the night of his thirty-seventh birthday. Twain looks a little like Scott Pilgrim but rather than modern day boy-pursuing-girl, this is an age-old struggle with love’s morally ambiguous enchantments. Romance, religion, spells, and myth are all explored as the Lorelei makes its misty voyages upstate and back again, the philandering Lafayette offering many a wise word on all such subjects. The 400 pages flow swiftly by (though you’ll want to be pausing to admire the rainsoaked scenery), the characters very much alive, gripping you with their conflicts both internal and external. As these boil over, the ending leaves one unsettled long after the turn of the final page, as such meditations on life and love are bound to do.

Young Albert

(Yves Chaland, pub. Humanoids)

Hats off to Humanoids for making more of Yves Chaland’s work available in English! This French master of the clear line/Atom style died all too early in 1990 at the age of 33 but what he left behind is very impressive. Humanoids brought out a collection of Chaland’s excellent Freddy Lombard stories years ago (we also see Young Albert drawn to the legend of Godfrey de Bouillon) and now there is this wonderful super-oversized deluxe limited edition of Young Albert released October 10th. A know-it-all kid from the projects of Brussels, Young Albert would be infuriating to know in real life. Always offering unasked for advice (often ridiculous or if there is any hint of practicality in these comments, they couldn’t be delivered at a worse time), he traverses the city and countryside manipulating his friends, engaging in dubious ways of making money, and often perpetrating physical aggression. Death and violence very much play a role in these vignettes, for the most part six panels each. But there’s a certain charm about them, offering a picture of life, and though this rapscallion isn’t loveable himself, Chaland’s excellent work certainly is.

Reggie Chamberlain-King writes:

Locke & Key, Volume 5: Clockworks

(Joe Hill and Gabriel Rodriguez, pub. IDW Publishing)

The finest American writing of the last decade has been in the long-form, on television and in comics, where the story-telling is tight, if not compact; sprawling, but taut. It is the run-on series, rather than the continuous soap, that fits modern expectations: a microscopic world that goes all the way down, somewhere the writers can go forwards, backwards, round, and deeper and deeper. In this fifth and penultimate installment of Locke & Key, by Joe Hill and Gabriel Rodriguez, Hill the writer goes further back, bringing into focus the troubled history of Keyhouse, a history as troubled as its present would suggest. As the children of the Locke family have already learned, the more one delves into the dark, the more inevitable the spread of darkness seems. In Volume 1, their father was brutally murdered, by Volume 5 it’s a wonder that they have not. Rodriguez’s spectacular artwork – including several beautiful funerals across the series – is the perfect complement to Hill’s turns of imagination, grounding every twist in a consistent aesthetic world. The great invention of the Keyhouse keys themselves – magic instruments that unlock the laws of physics – is all the more captivating by being so smoothly integrated into the reality of the book: Rodriguez’s work allows for such things. The Head Key, which grants access to one’s inner-most thoughts and emotions, is central to the series: psychology is made transparent; the fears, the secrets, and the dark passions of the teen heroes are available for peers and readers to see. Metaphorically, that which has been suppressed is unlocked, and, judging by the meticulous pacing and exploration of this series, so too will something worse be unlocked literally. With one chapter – Omega – left in this beguiling horror series, it would be wise to catch-up on the preceding five, so that you may better savour the anticipation of whatever conclusion is in store.

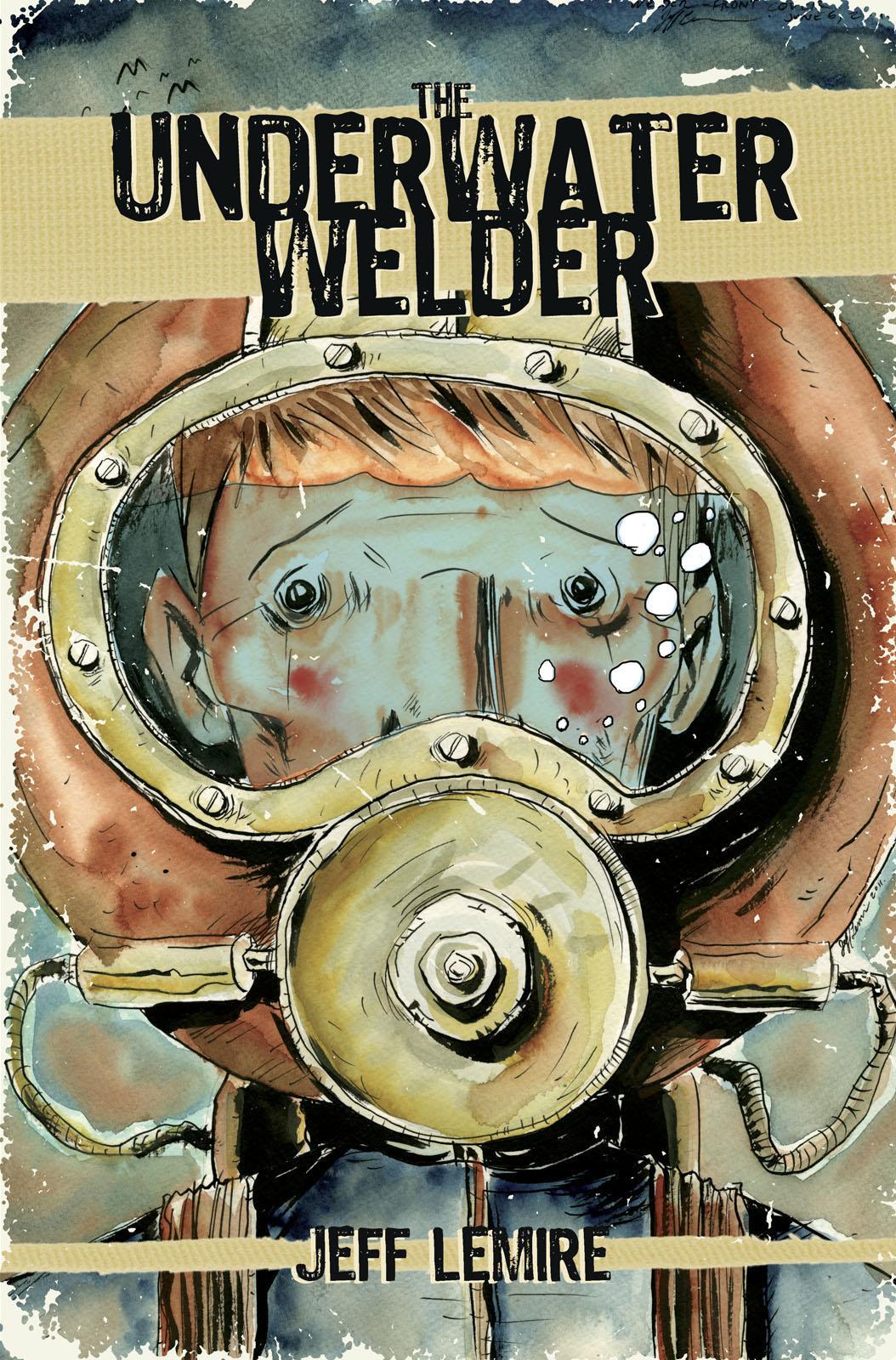

The Underwater Welder

(Jeff Lemire, pub. Top Shelf)

The Underwater Welder is an elegant metaphor, even if it makes for an inelegant title. The occupation is obscure and intriguing, but, as importantly, blue-collar and uncomplicated. It would be earthy, if it weren’t sub-aqua, and is certainly more captivating than the English degree that the protagonist leaves behind to pursue. At its heart, it is about diving beneath the surface to fix things and, for a character who likes to psychoanalyse and needs to be psychoanalysed, this is perfect. Jack is an expectant father who once, unfortunately, expected too much of his own father. His father, an underwater man himself, disappeared and left Jack to doubt his own capabilities as a parent and adult. It is circular, self-destructive logic that is told with a surreal clarity: Jack finds himself in a ghost town, where all the roads lead back; he is mysteriously returned to his childhood, where spirits remain. As Damon Lindelof observes in the introduction, it is like an early episode of The Twilight Zone, but used here to resolve the personal rather than the social. It is told beautifully. Lemire’s lines are all nervous and twitchy, while his shading alternates between the botchy and the scratchy. All of these are positive attributes when they contribute to the unnerving, tense atmosphere in the artist’s heavy seascapes: the sea and sky are still, but, look closely, and they’re shivering. This applies to the writing too, both literally and figuratively: the action takes place beneath the surface.