Gonna keep this intro short and sweet as we’ve got a lot to pack in this month. While Mat’s been releasing and touring Teeth Of The Sea’s excellent new album, Master, I’ve been busy listening the fuck out of it, and Reggie Chamberlain-King’s been performing The Play Of The Book at various literary festivals, quite a backlog of comics reviews have piled up. We’re pleased to welcome synthpop’s own Han Solo, Sean T. Drinkwater, who is letting us know how the adaptation of George Lucas’ original Star Wars screenplay is shaping up. And so without further ado…

Frederik Peeters – Pachyderme

(pub. SelfMadeHero)

I’ve spent the past few weeks raving about this beautiful work to anyone who will listen. An utter triumph from Frederik Peeters. This gorgeous surrealist exploration of the psyche, complete with spies and elephants, has a wonderful pervading sense of mystery, which remains even as we begin to grasp what’s going on. Carice abandons her car in a traffic jam (due to a dead elephant in the road) and hikes through the woods to find the hospital where her husband has been taken after an accident. Once there, both patient and staff behaviour hints at bizarre workings afoot. She wanders into a morgue whose inhabitants can all still speak, a female piano student love interest of hers keeps showing up, and Carice finally finds herself in the arms of a genius surgeon with deep secrets and a heavy drinking problem. En route to this great séducteur, babies keep appearing (walking, waving, tumbling), nipples grow out of a wall, and a giant flowery vagina materialises as an exit into the forest. Moebius provides an excellent introduction offering further insight into the artistry of Peeters’ chosen colour palette (flowing betwixt purple and green) and other aspects of his masterly technique. I can’t recommend Pachyderme enough. Aug Stone

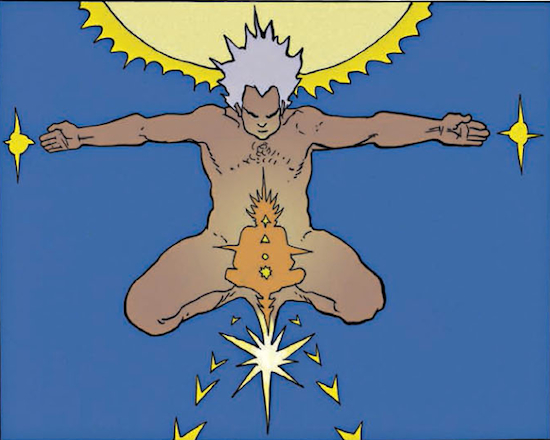

Alejandro Jodorowsky & Moebius – Madwoman Of The Sacred Heart

(pub. Humanoids)

This is like taking a rocket out for a joyride. In the frantic pace at which events unfold, the far-flung destinations traversed, and the fact that 60-year-old Philosophy Professor Alan Mangel impregnates his young student Elisabeth, who believes their child will be the second coming of John The Baptist. The staid professor thinks he knows of spirituality but his inner youth, manifested as a hallucinatory green demon, is determined to show him what he’s missing. Elisabeth seduces Mangel inside Sacré-Couer and from Paris, via the company of drug addicts, escaped mental patients, and radical revolutionaries, they seek refuge in Israel before being swept off to the jungles of Columbia. Sacrilegious in the extreme with respect to the Church, I’d wager there’s something in here to make everyone squirm and for me it was the extended scene of disciples supping from the androgynous Messiah-figure’s slit wrists (seriously, they flow for three pages). It’s a mad, mad story but ultimately a holy one as Jodorowsky has often written of the need for inner transformation in order to truly experience life. For Alan Mangel it’s not exactly the merging of your light and dark sides as in The Incal, but rather uniting the energy of mind with the intuition of the heart. Enter Doña Paz, a magical healing figure a la the real life witchdoctors Jodorowsky knew and associated with during his time in Mexico City. It needs to be pointed out too that Moebius’ art is outstanding, my favourite of everything of his I’ve seen. And the work of colourists Florence Breton, Daniel Cacouault, Zoran Janjetov, and Scarlet Smulkowski really help bring this fantastic fable of the lifeforce to life. Aug Stone

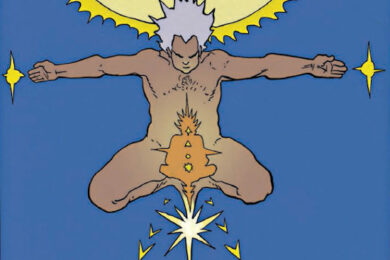

Renaud Dillies – Betty Blues

(pub. NBM)

NBM continue to put out the ‘magical graphic novels’ of Renaud Dillies. His Eisner and Harvey nominated collaboration with Régis Hautière, Abelard (reviewed in August) is still one of the best things I’ve read in ages. And Dillies’ first book, Betty Blues, winning Best Debut at the Angoulême Comics Festival after its release in 2003, and now available for the first time in English, is up there. Continuing with his avian-focused anthropomorphia, Rice Duck is a jazz trumpeter in love with Betty, who leaves him in pursuit of more champagne. Realising he’s been paying more attention to ‘this life of monomaniacal musical has-beens’ than her, Rice tosses his trumpet off a bridge and Dillies lets the story flow wondrously where it will, following the course of this instrument along with Rice and Betty’s individual paths (and twisting them all together in a dream sequence down deep in Rice’s guts). Dillies’ style is both fluid and scratchy, as characters, thoughts, and emotions seem to etch their existence onto the watery course of life. Poignantly seen on page 14 as Betty sees Rice materialise in her cup of coffee and also in the shifting rainy perspective of the ending. Betty has been growing weary of her new rich beau’s corruption, while Rice attempts to forge a new life away from music, finding a true friend in an ecoterrorist owl who ‘revives his sacred fire’. Dillies conjures up levels of sadness with ease, but never without humour, love, and the other currents that give life meaning, summed up in the words “despite heartbreak, life remains so beautiful”. Stay tuned for a Quietus interview with M. Dillies. Aug Stone

Amy Mason with Eddie Argos & Jim Moray, illustrated by Steve Horry – The Islanders

(pub. Nasty Little Press)

From their first flat on their own, situated on a roundabout, to their 1999 holiday together on the Isle Of Wight, all the while secluded on the island-thought-impenetrable that is teenage love, The Islanders recounts Amy Mason and Art Brut’s Eddie Argos’ late-90s relationship. Stylishly illustrated by Steve Horry, this is the book of the stage show, where Amy reading the story would alternate with Eddie telling his only slightly differing side via song (an album of these, along with PDF of the book, is available at Bandcamp). Punctuated with postcards, sent ‘c/o the 90s’, to their younger selves, Mason tells of the reality of youthful destitution, without any particular fondness glitzed up by memory. But in hindsight, to the reader at least, after you’ve made it through all that, those times when all you needed was music and somebody to love always sound fucking romantic indeed. How much work went into making mixtapes because they were just such so important – ‘full of Angelica, Kenickie b-sides, Ciccone, Bis’ – vital to one’s existence even, while the basics of how the rest of the world functioned seemed almost impossible to comprehend. The writing is excellent. Little things, like the repeated mention of a passport which eventually leads to a way out. Or early talk of ghosts foreshadows a possibly haunted B&B, and then learning of the plethora of phantoms famous for keeping company on the Isle of Wight. And of course the feeling that she’s summoned up quite a bit of what they encounter by her remote advertising job. All of this dashingly displayed in Horry’s drawings which often have a certain Steed & Peel Avengers or even The Prisoner-esque flair. This may or may not be intentional but seems well suited to the setting where they are greeted by a smiling bus driver who beckons them aboard and gives them a packed lunch. Plus, as a friend once commented, Horry ‘always draws cool hair’. And finally the songs are all good, Eddie Argos’ own brand of Britpop, with ‘Somewhere Over The Solent’ being the highlight. Aug Stone

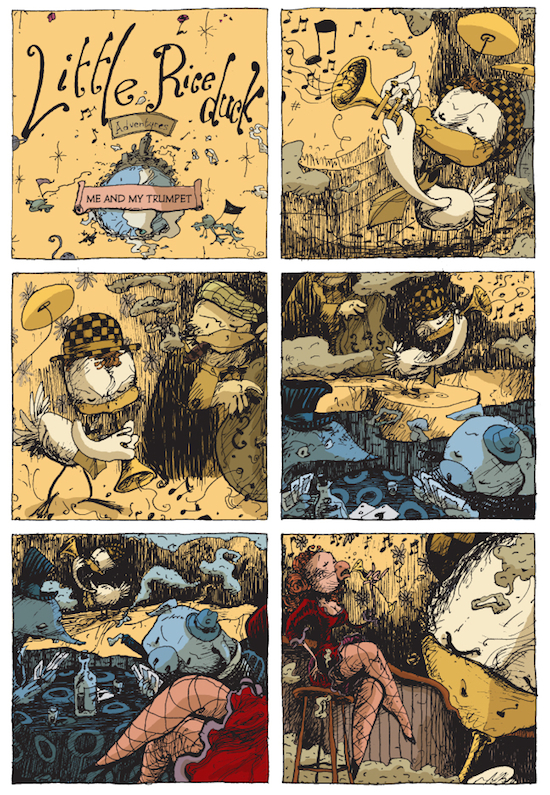

Matt Kindt – Red Handed: The Fine Art of Strange Crimes

(pub. First Second)

A fine artistic achievement told in Kindt’s lovely signature style. A la Super Spy, the narrative moves in segmented, seemingly non-linear bursts, adding up to quite a tale. And beautifully done so that within the individual storylines also, elements piece together, sometimes literally, to create something whole. All while being a philosophical discourse on art, crime and morality, the individual and the State. Newspaper reports hale Detective Gould as a hero by as he ceaselessly solves every case that comes his way. But the irony of this is felt as we follow his questioning of a suspect with links to a spate of recent transgressions. Through a series of word balloons in an otherwise darkened room, an overview of much deeper, darker significance emerges. What could connect a chair thief with plans for ‘the ultimate heist…the Fort Knox of chairs’, a one-time art thief-cum-dealer offering collectors a clever discount solution, and an elevator repair man with a spy camera on his tie (just like Gould)? Or these characters to a failed novelist with a pitiful axe-to-grind who nevertheless manages to construct a genuine work of art via its means if not content? Others still offer substance obtained by deception and contribute considerable transgressions to the shocking master crime revealed in the final pages, the wider consequences of their actions unbeknownst to themselves. Kindt’s storytelling is superb, with unique ideas abounding and a great amount of information conveyed most economically. This is best seen in the way motives are presented and understood in two-three panels, never slowing the flow or altering its course. Aug Stone

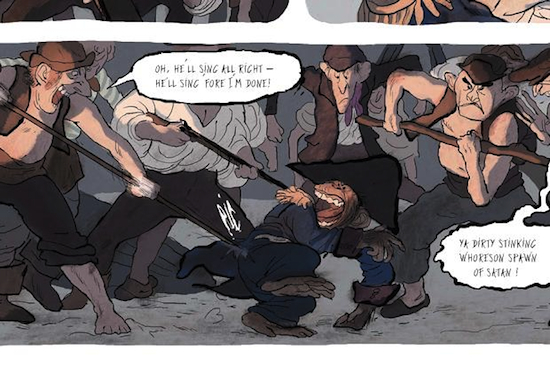

Wilfrid Lupano and Jeremie Moreau – The Hartlepool Monkey

(pub. Knockabout)

British readers will probably have heard of the Hartlepool monkey, being the reason that the fair folk of Hartlepool are still called Monkey Hangers by the rest of the country. During the Napoleonic wars a French ship sank off the coast of Hartlepool and it’s mascot – an ape dressed in French naval uniform – was washed ashore, mistaken for a French naval officer by the residents of the town, tried and hung. Pretty funny, right? Well yes, and Lupano and Moreau’s treatment of the story doesn’t shy away from its comic elements (mostly at the ignorant townsfolk’s expense) but there’s a lot more packed into this graphic adaptation – perhaps a bit too much at times. The Hartlepool Monkey is an earnest treatise on the dangers of nationalism and a damning indictment of xenophobia that veers from broad physical comedy to tragic irony. That it’s nonetheless such an even and enjoyable read is mainly down to the skill of Moreau, who’s work here is exceptional. His furious linework beings to mind a cross between Gerald Scarfe and the animations of Sylvain Chomet and is only let down by a slightly flat digital colouring job that strips away some of his immediacy. Lupano’s script is packed with gags, some effective, some groan inducing, and only loses its way with a final unnecessary twist that does nothing to further the story. However, all the most powerful moments belong to the titular simian; his reminiscences are heartbreaking and his final cruel and unavenged treatment is truly tragic and given shocking power by a series of dramatic splash pages that play out with an ironically Old Testament-like force. Mat Colegate

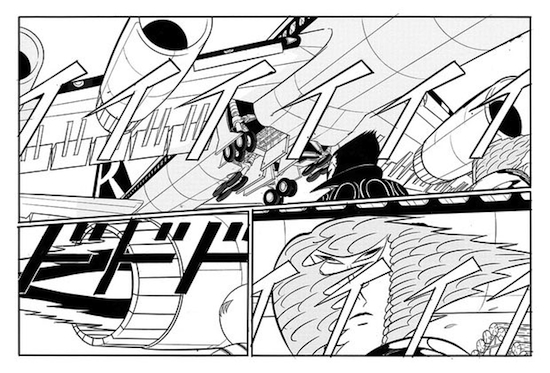

Yuichi Yokoyama – World Map Room

(pub. Picturebox)

As with a lot of avant-garde work, the trick with Yokoyama’s World Map Room lies in surrender. Rather than trying to puzzle out the meaning of his oblique yet slight book, just abandon yourself blissfully to its rigorously maintained sense of internal logic and its sheer impenetrability. The story is non-existent (Yokoyama has described the book as a ‘gekiga’, meaning ‘dramatic pictures’ but there is very little drama at all). A group of men enter an unfamiliar city, walk about a bit, meet some other men, go and look at a boat that has sunk into a pond and that’s it. The fun – and it is fun – comes from Yokoyama’s incredible style; his oblique dialogue, intrusive use of sound effects and meticulously rendered cityscapes are mind boggling, forcing the reader to slow down in an effort to take it all in, so that reading the book becomes almost an act of meditation. Couple this with his superb layouts and fascinating eye for alien details and reading Yokoyama’s work becomes an experience like no other. Gloriously strange. Mat Colegate

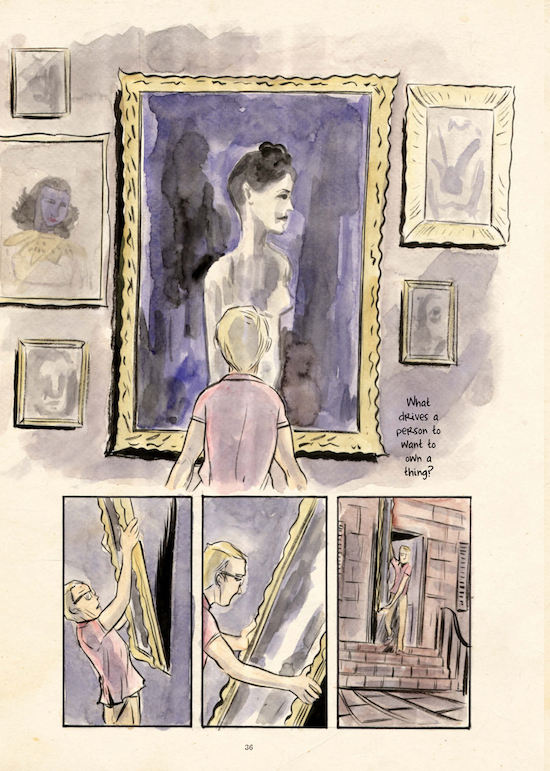

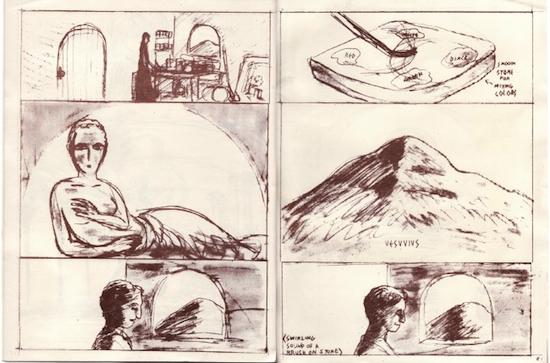

Frank Santoro – Pompeii

(pub. Picturebox)

I’ve always considered Frank Santoro to be a bit of a cartoonist’s cartoonist and that’s certainly not a view that got much changed following my reading of Pompeii. It’s immaculate; every panel weighted and balanced, thematically precise, the drawings leading your eye round the page with an accuracy that most cartoonists would kill to be able to achieve. The only criticism I would have is that the story – which concerns the travails of an artist’s assistant in the days before the famous volcanic eruption that destroyed the titular town – is extremely slight. It feels as if Santoro came up with the themes and techniques he was going to use and relegated the plot to being of secondary importance. There’s nothing wrong with this, of course (that’s precisely the reason I love the Yuichi Yokoyama book) but it could lead to someone a little less au fait with the technical side of comics storytelling (me, for example) to ask what the point was. Griping aside, this is a lovely book. It’s lightly sketched, dusk brown artwork is a perfect fit for its setting. Even the rough card paperstock evokes the stone walls of the doomed city. It’s just that, like the paperstock, its a little dry. Mat Colegate

Robert Crumb – The Weirdo Years 1981-’93

(pub. Knockabout)

Oh Robert…oh Robert Robert Robbie-the-Robot Crumb, what am I going to do with you? You are so so talented, Robert Crumb! So very very talented! I believe you are probably the most talented cartoonist of the whole great flowering of American alternative comics (everyone says this, I know, but you are!) Evocative, vital, all those words that essentially just mean ‘really good’, you are all of them, Robert Crumb. But this work, from Weirdo magazine, which you started in 1981 with your wife… I’m afraid a great deal of it just fucking repels me. It’s your subject matter (and I know that it’s only one facet of your considerable talent, but it’s one that has a great deal of representation here). I cannot get with it, Robert Crumb. The constant wearying horn-dogging, the grinding belittlement of yourself and the others around you (especially the women). I just…gah! What makes it so painful is that the parts of this handsome collection where you meander into pure surreal abstraction, or present a biography of Philip K. Dick, or whatever, are so so fucking good. Next level stuff. What incriminates is the presentation of some of your stories as photo strips. Now, I can see why you did this; they are firmly in the tradition of the self improvement photo stories of yesteryear (all that ‘John used to get sand kicked in his face, but following the Charles Atlas programme…’ blarney is very evocative, isn’t it?) However, stripped of your brilliant drawings, it goes to show some of your ideas for what they are: sexist horse shit. This isn’t fair, of course. Your work is a product of its time, y’know, the great liberated sixties and all that, when the men were men and the women were… wait… this was produced in 1981? No excuses, Robert Crumb. No excuses at all. Mat Colegate

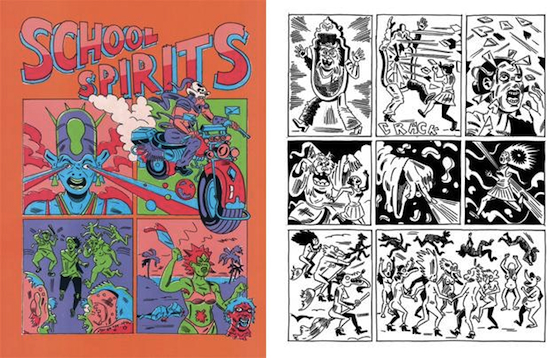

Anya Davidson – School Spirits

(pub. Picturebox)

This is a weird one. Anya Davidson is a member of Coughs and there’s plenty of the noise and spit and sparkle that informs that band on evidence here. On first reading I had absolutely no idea what to make of School Spirits. It seemed wilfully obscurantist. Every time I thought I had a handle on it it would veer of in another direction, powered by Davidson’s messily psyched out black and white artwork and clinging to no sense of logic but its very own. But, after I’d slowed down a bit and allowed its cast of school kids, werewolves, black metal stars and magicians to do their strange dance in front of me, it all began to make more sense. This is a comic book in which everyone’s interior state – their every fantasy and reminiscence – is allowed to fizz messily into life with no fear of the consequences. This commitment to its characters means that the going can get a bit tough to follow, but it’s a creditably thorough way to tell a story (no matter how disconnected) and set off a treat by Davidson’s madly psyched-out, punch drunk drawing style. Davidson’s level of invention is also considerable; nearly every panel is crammed with grotesque characters, all rendered inventively with no slacking or short cuts being taken and her trip sequences are whacked out and immense. Don’t take my word for it on this one, buy it, stock up on cough syrup, clear an afternoon and strap yourself to something solid. Wild times. Mat Colegate

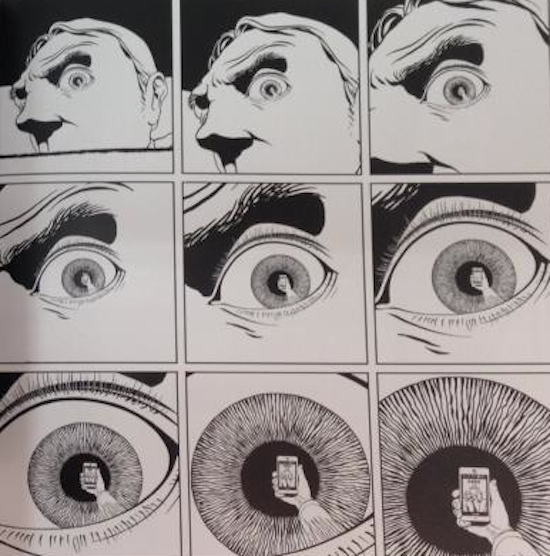

Marc-Antoine Mathieu – 3"

(pub. Jonathan Cape)

It is usually a bad thing if a piece of art makes seconds feel like hours; I’ve sat through Wagner twice. In fact, I’ve drowsily tilted to one side through Wagner once.

For Mathieu to extend 3 seconds over 80 pages of 3×3 grids, approximating 720 equally-sized panels or 240 panels per second, seems unreasonable. And yet, in that time, a photon of light travels 900, 000 kilometres, which is a great distance to cram into such a thin volume.

Told from a photon’s point of view, with all a photon’s agency, this murder mystery ticks over at a slow tempo and a very regular rhythm. The particle follows its path, panel after panel, closing in on each item until reflected from yet another shiny surface. In this way it reveals all the clues, as the world, for all photon knows of it, stands still and the infinite particle ricochets about the facts. From mirror to windowpane to mirrorball. It has the strange ponderous feeling of trying to magnify a particular area in Photoshop, then being returned to the start.

This is how action is conveyed now, since the Matrix at least. When confronted with a crime scene, any of the modern Sherlocks will freeze the moment and take in everything: within a second, the case is solved and the bad chap knocked off balance or unconscious. Now we can all experience it, each exquisite detail, beautifully rendered. We can scan each scene, like a Where’s Wally? book, but the slow, anti-gravity movement of the story takes us away from the solution just before we grasp it. The beam bounces about a bit, from French sidestreets to suspect hotel rooms, deflected off a lady’s compact, a lightbulb, and into space.

That is how it feels: to be floating in space, drifting through matter and vacuum, until the photon eye careens into a satellite and is sent to Earth again. The cosmic scenes are the finest, because regardless of the corruption and the barbarism we glimpse as the light careers about, it is all over in an instant, while the black of space goes on.

The mystery is a deep one. It can be explored through the comic’s website and discussed on forums, but the mystery is hardly important. It is French. It is existential. And it is sad. The world turns and light propels itself onward, taking with it what we see and heading toward what we will see. In this case, what we see is frequently beautiful and frequently horrific, but whether time speeds on or slows down, there is little that we can do about it: we are spectators. Reggie Chamberlain-King

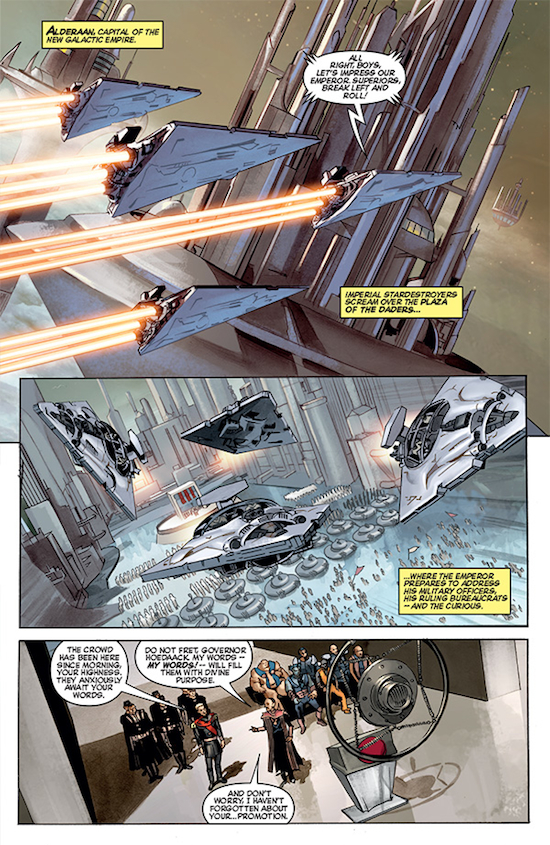

George Lucas, J.W. Rinzler, & Mike Mayhew – The Star Wars Issues 1 & 2

(pub. Dark Horse)

The Star Wars comic series is an interesting idea for serious fans of the films, and the artwork is very nicely realized. There are several nods in the direction of original concept artist Ralph McQuarrie, something every Star Wars fan should rejoice in, and something which has been painfully absent since the original trilogy, save for this series and the upcoming Rebels animated television show. It’s fun and a treat to see where some of the original concepts were headed. Unfortunately it does also highlight some of Lucas’ weaknesses.

If you’re not familiar with the concept here, The Star Wars is a comic version of Lucas’ 1974 first draft of what became Episode IV. It bears very little resemblance to the film which was actually released, having been reworked three times before finalising the shooting script. It should be known, for those that do not, that George Lucas had a very bad time making the film now known as A New Hope and had an equally bad time, albeit for different reasons, overseeing the follow up The Empire Strikes Back, long considered the real victory of the franchise.

These two experiences helped mould Lucas into the childhood-savaging control-monster that he became for decades. When left to his own devices and without people (producers/directors/editors) to say ‘no’, Lucas’ stories become a bit one dimensional, as we see in the prequels and this early draft. It’s overly bureaucratic and political, like Dune without the weirdness. The plot is muddled. Without giving too much away, the energy and the character archetypes will be familiar to those who can quote A New Hope. Jedi training, the attack of the Death Star, the overconfidence of the Imperial forces all come into play. It kind of works from a technical perspective, but there’s not much heart in it. In the middle of an attack on what is the Death Star here, there is literally a discussion about going ‘over budget’. The dialogue is clunky, the exposition clumsy, and these are all problems Lucas is especially well-known for since the prequels.

That being said, having been previously familiar with this draft, I enjoyed the comic a lot more than a straight read. This was perhaps because, besides the terrific art, this Star Wars universe exists independently of the ‘real’ one. Character names and concepts from the films are not applicable here, although they do appear. Vader, for instance, is just a good old fashioned bad guy/henchman, without his signature helmet/breathing mask. ‘Annikin’ is another character altogether. There are even a few surprises (note: I’ve only read the first two installments). Again, if you’re a big fan of the franchise or even if you just love the McQuarrie artwork style, there is a lot of charm to this series. Sean T. Drinkwater