In a month in which extreme unpleasantness has bubbled to the surface almost everywhere, so too for comics. Much airing of grievances is taking place, and I’ve read a distressing amount from women who have been the victim of predatory and coercive behaviour in the comics world, particularly at cons. The first I saw of it was accusations against Warren Ellis (not the Bad Seed, to be clear, but the comics artist), to which he responded a couple of days later, not to universal forgiveness. Since then, Charles Brownstein has resigned as executive director of the Comic Book Legal Defense fund after allegations against him resurfaced, and new accusations against other senior figures in the comics world have been appearing on a daily basis.

On a more positive note, one of the pleasures of recent months has been the comics Simon Hanselmann has been posting on Instagram. He began a non-canonical Megg Mogg and Owl saga on the 13th of March, and it is wild. As crazy and terrible things have happened in the world, he’s reflected this in the story. I’ve no intention of spoiling it for anyone who hasn’t read it, but arguably it has even transformed into what could be the only superhero comic I’ve ever wanted to read. It’s brilliant stuff, hopefully to be collected in print one day. I’d link you to the start but I am an Instagram novice who created an account solely to read this, and I can’t. If you can find it, though, read it. He has a new book Seeds and Stems due out soon – look for a review next time.

The arts continue to struggle horribly with the effects of lockdown, so if you do buy anything reviewed here, make sure to see if you can order direct from the artist, publisher or an independent comic shop. The cancellation and virtualisation of the summer’s comics events has cut off a crucial revenue stream for many, so please show your support.

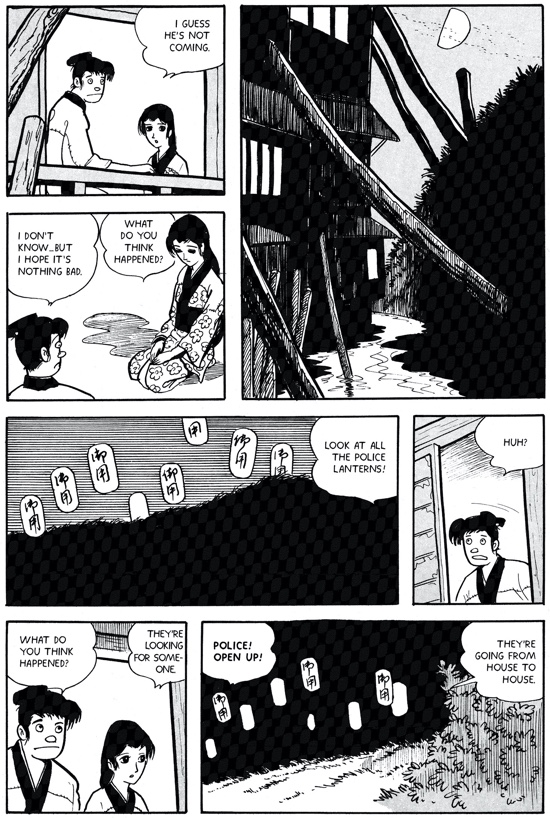

Yoshiharu Tsuge – The Swamp

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Last Behold! included a review of Tsuge’s The Man Without Talent, including some of his losely autobiographical work from the 1980s. This time we have the first in a series of releases from Drawn & Quarterly comprising work from much earlier in his career. Once again Ryan Holmberg provides the translation but this time the accompanying essay is by Mitsuhiro Asakawa.

Tsuge’s early career included writing stories for the kashihon (rental manga) market in the 1950s when he was a teenager, and he redrew a number of those in the mid 60s for inclusion in the influential Garo magazine, included here. Unlike his later output, several of these are historical stories of samurai and ninja, although the struggle of poverty is a linking theme throughout. Opening piece The Phony Warrior is an account of the meeting between a samurai and an anonymous ronin at a hot spring in the mountains. Speculation about the identity of the mysterious ronin leave the narrator reflecting on how much we must endure just to live our lives and how little of this may be obvious to the casual observer. Even at this early point in his career there is a pervasive melancholy, reflective quality rather than a reliance on conventionally exciting narratives.

Although there is a rare happy ending in one story, The Secondhand Book, the approach he takes in Chirpy is much more common, where an unhappy couple buy an expensive bird and tension builds as we know something is going to go wrong. Start a story, think of a bad outcome, and you’ll be in the right area, but Tsuge always has the capacity for surprises. His bleak, low key endings rarely offer redemption, at best bittersweet if it comes. Throughout the work here beautifully detailed establishing panels are used to show the setting, switching to much more simple panels to foreground the action. This excellent collection is a great introduction to Tsuge’s early career, and I can’t wait for the next volume. Pete Redrup

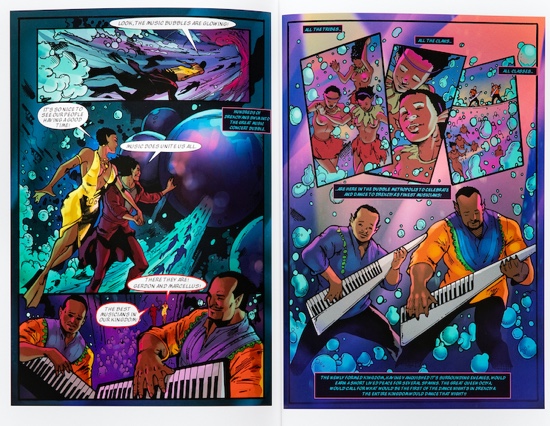

Abdul Qadim Haqq – The Book of Drexciya Vol.1

(Tresor)

The Afrofuturist mythology created by ur/UR Detroit electro act Drexciya is explored in this book written by Abdul Qadim Haqq and Dai Sato and illustrated by a variety of artists including Haqq, famous for his seminal Detroit techno artwork. Beginning in 1553 with pregnant African women thrown from slave ships and taking us to the 1990s, we get a series of stories set in the same mythology, collected in a lavish hardback from Tresor.

As they drowned the murdered slaves gave birth, and their children were rescued by goddesses of the seven seas. Able to breathe underwater as they had in their mothers’ wombs, these children became the first Drexciyans, and eventually, the wavejumpers, the strongest warriors of Drexciya. You don’t need to delve too deep into the Drexciya back catalogue to connect the comic to the music – 1997 compilation The Quest is full of track titles that align to the events here, from Sea Snake through Red Hills of Lardossa and Wave Jumper to Bubble Metropolis (if you’re not familiar, all unquestionably fine pieces of music). Indeed, it was in the sleeve notes for this album that fans first began to learn about the ideas behind the records. Writing this review in the week that the watery fate of a statue of Edward Colston provokes more outrage from some of those in this country than the murder of George Floyd certainly throws things into sharp relief, and this mythology gives lie to the notion of electro and techno as music without a message.

The stories here cover the creation myths, an important discovery that advanced the Drexciyan’s scientific knowledge considerably, a major battle, a dance party, and finally a glimpse of their society over 400 years later. There is a certain thrill to be had connecting these with the music, and a synergy from reading while listening, the futuristic sounds a perfect match for the undersea images. Artistically, there is a visual slickness that is more at home with larger, more mainstream publishers than tend to find their way into Behold!, and this is particularly true with the colouring. This aspect of the aesthetic is not so much to my taste, but the ideas are fascinating, particularly in the context of the music, and Drexciya fans are definitely going to want to pick this up. Pete Redrup

Noah Van Sciver – The Complete Works Of Fante Bukowski

(Fantagraphics)

We reviewed the first two Fante Bukowsk books here at tQ but somehow missed the third, an omission we get to rectify with The Complete Works Of Fante Bukowski. Continuing the trend of outstanding book design, this lovely hardback looks like a Library of America edition complete with appropriately grandiose notes on the dust jacket flaps. As well as all three books, this includes some poems from one of Fante’s zines and twenty visual tributes by other artists – if you’ve ever wondered what Bukowski would look like drawn by John Porcellino, this is for you.

The third part finds unsuccessful writer and successful drunk Fante still living in Columbus, Ohio. He is still writing poems and making zines. He is still being supported by his parents, although, as always, this doesn’t work quite as smoothly as he’d like. He’s getting much more press than before – the running gag is that this is due to his friend, a sex worker whose clientele seems to mostly be journalists. We also get a series of flashbacks from four years ago, when Fante (or rather, Kelly, since he had yet to change his name) was an emo practicing guitar in his bedroom. After being laughed off stage in a failed attempt to be a one-man emo band, key to the failure being the fact he didn’t bring a guitar, Kelly retreats to a bar to lick his wounds. The fact that he can write lyrics but can’t actually play the guitar leads to a revelation, and from this point onwards he considers himself a poet rather than a musician, as well as a barhound.

The Fante Bukowsk books have always been Noah Van Sciver’s funniest comics, and this collection showcases Fante’s journey from talentless egotist to what could be considered a redemptive ending in terms of family, friends and career. It’s an excellent volume, very highly recommended. Pete Redrup

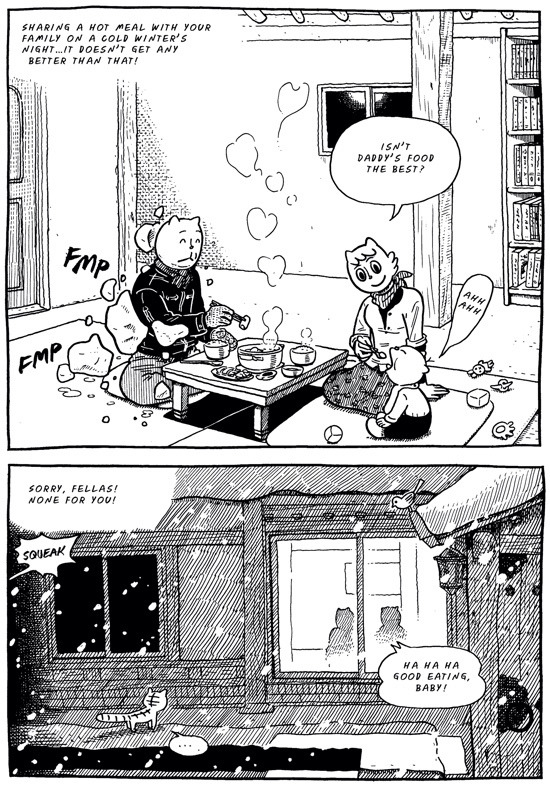

Yeon-sik Hong – Umma’s Table

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Umma’s Table, a sort-of sequel to 2017’s Uncomfortably Happily, has much of the same charm as its predecessor. Artist Madang rents a countryside home with his wife and baby, hoping to settle down to life outside Seoul after many apartment moves. As with Yeon-sik Hong’s previous book, the idea of living a simple life in tune with nature is very important here. Much is made of the seasonal weather as the family are trapped at home by snow then delighted with the emergence of spring greens that Madang cooks for his family. Food is a way of staying in touch with nature, a vehicle for nostalgia as he remembers his childhood and also the way he likes to care for his family.

The importance of food for families is one of two central themes – an early section looks at the annual kimchi-making where Madang’s mother would ferment 100 head of cabbage which would provide food for much of the year. There are numerous flashbacks to childhood which usually feature food preparation, often the staples the mother would make that would feed the family for months, like kimchi or soya bean paste. His happy childhood memories revolve around eating and this is a tradition he wants to continue with his own family, getting up early to prepare elaborate healthy meals based on produce from his own garden.

As the family settle into their life in the countryside, the second motif of the book emerges. Madang has to constantly return to Seoul to look after his ageing parents who have complex health needs and live in a depressing underground apartment. His beloved mother, provider of his happy childhood memories, is seriously ill and his alcoholic father is incapable of looking after her. Madang and his brother Maru take turns to look after her and share the hospital bills, and this takes a heavy emotional and financial toll.

Yeon-sik Hong has produced a book exploring something we can all relate to, how we care for the people we love, particularly when they have competing demands. This time, he draws his characters as anthropomorphic cats (quite distinct from the feline pets that also feature). He reminds us what is important in life, but also how we can feel like we could always do more, and the importance of making peace with this. Pete Redrup

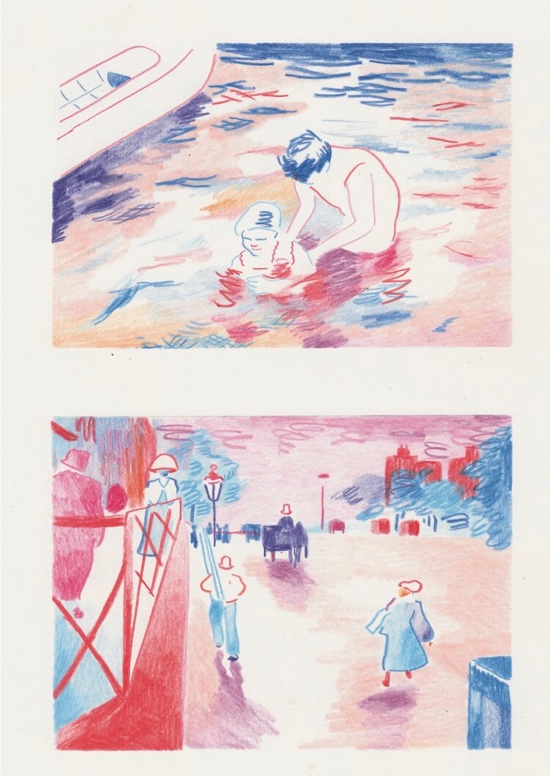

Antoine Cossé – Palace No. 1

(Breakdown Press)

A compilation of clever, beautifully rendered strips from Antoine Cossé are collected in Palace No. 1, an imaginative second issue that’s shaping up to be a promising series.

Released by the always consistent Breakdown Press, Palace’s opening issue is composed of three parts – two complete tales and the first part of an intriguing ongoing story. The book itself is beautifully designed, with Cossé’s elegant penmanship bookmarked with flashes of vibrant artwork.

The first section, Plague – oddly prescient in the current climate – centres around a mysterious figure living in isolation. After a nearby medieval town is struck down with a devastating disease, the desperate locals look to sacrifice this unnamed figure to appease whatever is causing the virus. Cossé excels at depicting a creepy plague doctor stalking the gloomy scenes of destruction in this dark and moody tale, which edges just on the right side of fantasy.

The second, and my personal favourite of the three stories, Guards, relates to a pair of despondent and underfed guard dogs at a futuristic prison. Between grumbling about their meals and sharing gossip of debauched human guards, they witness a jailbreak in progress. A tale that explores the fragile loyalty of a hungry dog, Guards is a charming self-contained story illustrated using ink and grey watercolours.

The final section of Palace No. 1 is the beginnings of Alphonse , an ongoing story that begins with a thrilling robbery in the centre of Paris. Following a gunfight, mounted police rampage through the city in pursuit of two robbers who peel away into the wilderness. Deep in the woods we are introduced to Alphonse, who is being photographed by a lake. How these two plots diverge remains to be seen in the next issue, but the beautiful artwork and entertaining opening scenes left me eagerly awaiting the release of Palace No. 2. Joe Marczynski.

Lynda Barry – Making Comics

(Drawn & Quarterly)

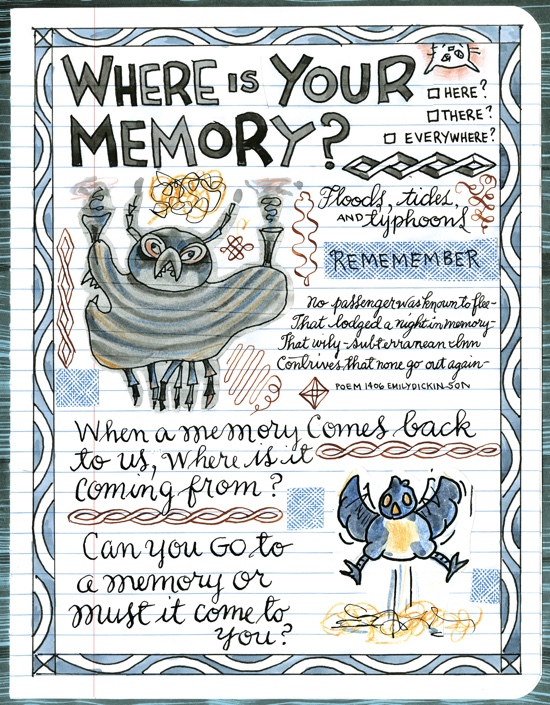

Lynda Barry’s immersive work continues to engross. Making Comics (from 2019) is the Barry book which is most explicitly a guide about comics, although it can also be cast as part of a series of meta comics which thus far includes What It Is and Syllabus. Scott McCloud’s 1993 book Understanding Comics still has something of a monopoly when it comes to comics about comics, and about how you, too, could make one. While McCloud’s book functions perfectly as a series of didactic steps for the aspiring cartoonist, Barry’s collage feels more revelatory, like comics’ subconscious being brought above water, and is also more theoretically rigorous. Few have done as much as Barry to analyse and present the perplexing possibilities that are open to creators of “graphic narratives.”

Making Comics features Barry’s trademark marginalia, scans of newspaper clippings, painted cartoons, and obsession with handwriting. Additionally, and very much on-brand, this book depicts childish things but is too much like a psychoanalytic submersion into images to be considered anything other than adult. Hillary Chute wrote in 2010 about Barry’s use of “the rhythm and narrative interplay of comics to give form to traumatic events in childhood,” though trauma is much less of a focus in this instance. Making Comics finds something emancipatory in childhood activities. It is instructive, and avowedly a teaching tool, yet the words themselves remain imagistic and the borders are hallucinatory, like a lesson provided through the lens of one of William Blake’s illuminated manuscripts.

This book reinforces the fact that the beauty with creating comics is that inexperienced authors can get over the hump of having to feel like they need to represent something in a life-like manner. For Barry, the stranger and more unique the representation the better: the most important thing is that the page is alive. She wants artists to retain a child-like pleasure in being energetic with basic materials and seeing the unbelievable in a few doodles. In Making Comics, Barry synonymises this style of drawing with "a form of dreaming." Less skittish than some of her previous books, there is a dream-like quality within these pages, especially in how the colours – like ambiences – mutate between different headings and themes. Making Comics joyously reveals to the uninitiated and aficionados alike the medium’s potential magic. Nicholas Burman

Blutch – Mitchum

(New York Review Comics)

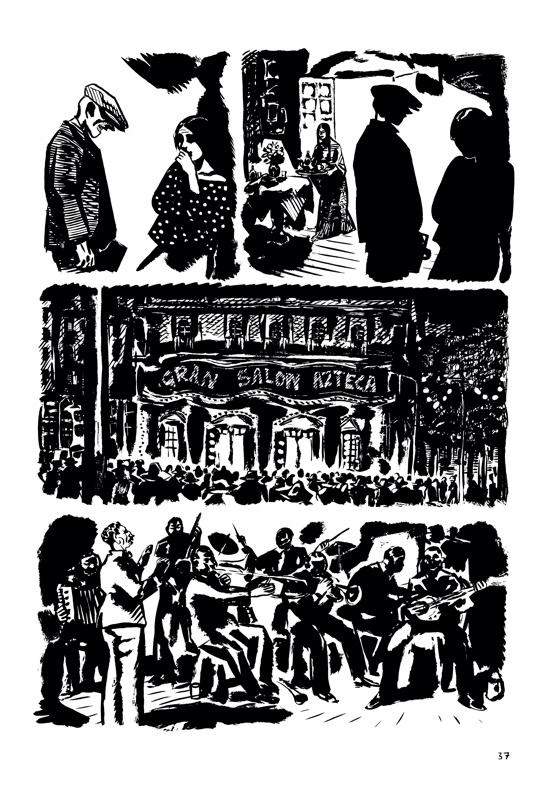

France and America have reflected each others’ supposedly national cultures back to each other in a web-like network of references that is hard to untangle. In the context of comics, French artist Blutch has very much been part of that process, as this book demonstrates. The last translation of his work into English, Total Jazz, published by Fantagraphics, comes with a publisher’s note that claims that comics and jazz are two “quintessentially American art forms.” This statement misses the point that no art form is quintessentially of any political geography, something that Blutch’s work makes self-evident.

Blutch has become a prominent name in the European scene since his emergence as an artist in the late 80s, working for renowned French publishing house L’Association, and contributing to Libération and The New Yorker. This, the second translation of his work into English published through New York Review Comics, is composed of vignettes which were serialized in the 1990s under the title Mitchum. Nothing apart from the name of the series relates the instalments, other than they mostly seem to depict some frenzied imagining of American culture – the America that is known to us Europeans who have only ever visited the country via movies and music. One of the two chapters explicitly set outside of the States is a depiction of an artist galivanting around Paris. Nevermind Blutch’s nationality, it’s the sort of imaginary one may expect an American artist to cook up while dreaming about an excursion to Europe.

As everyone reviewing this project has pointed out, it’s the art which makes Blutch so enticing. His thick chalks and scratchy pens result in smoky environments and characters that, though captured on the page, display a great sense of movement. Seeking to distil movement and some combination of romance and lust in formal visualizations, his style constantly pushes towards abstraction. The appendix of unpublished and unfinished work, whose content leaves a little more page space on the page than usual, will no doubt satisfy completists. I have to say the stories themselves here are less engaging. The female muse trope, regardless of whether its deployment in this book can be categorised as sincere or postmodern, feels instantly tired. Blutch may not be quintessentially French, but the vibrant, vibrating bodies of Mitchum are quintessentially Blutch. Nicholas Burman

Various – Kutlul #11

(Kutlul)

image credit: Vera Bekema

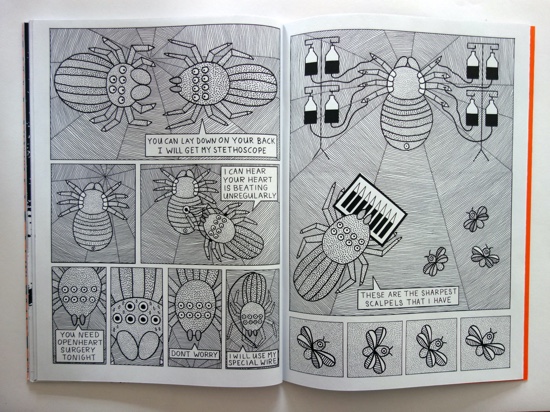

Dutch-German underground comix anthology Kutlul published its eleventh instalment earlier this year. The small press zine was cofounded in 2016 by artist, curator and Rotterdam resident Joost Halbertsma, and Dirk Verschure, a Dutch animator and cartoonist based in Berlin. They have been producing online and printed comics since graduating from Breda’s art academy in the early 2000s. Kutlul has featured an exciting array of underground art, and is typified by its interest in the surreal and the darkly humorous. The title of the series is a Dutch neologism that roughly translates into “ctdk,” as in: “Dominic Raab is a right kutlul.”

The zine has often been bi- and trilingual, though #11 is a great starting point for an Anglophone audience to come on board with it because a large majority of this issue is in English. No matter if you’re lacking the language skills required to read the text, there’s some fantastically visceral and vibrant black and white artwork to enjoy. Christopher Sperandio apes the action-oriented direction of golden age US comics for satirical means, while Vera Bekema uses precisely placed dots and lines to fashion a spider’s world dominated by textures and patterns.

Featuring 23 contributions, there’s far too much good stuff in Kutlul to summarise here, so I’ll conclude on a couple of personal favourites. Peter Vianen’s piece is a distorted sermon inspired by psalms 51, 06 and 32. His three panels take up one page each; their splintered interiors are reminiscent of a stained glass window. Inside the shards is all manner of violence and disorder. Elsewhere, Halbertsma’s own addition is of one image split between multiple panels. As you piece the environment back together you get the impression of an anxious and partial existence, the type quite common in days of isolation and quarantine. Do check out and support this anthology series, you’d be a kutlul not to. Nicholas Burman

Disa Wallander – Becoming Horses

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Disa Wallander is a Swedish artist whose mixed media approach has been grabbing peoples’ attention. She includes photography, collage and 3D materials on the page, along with paints and cartoon characters rendered in pen. This creates a strange dualism on the page between obviously invented personas and documentation of “real” stuff. The dreamy, ungraspable landscape she presents the reader with befits her adopted philosophy, which seems something akin to Kant’s contested term of idealism, the result of which is a practice that seeks to find some emotional truth amongst the conglomerated debris of experience. In the 1950s these characters would have been captured in amongst a nuclear familial setting; Wallander does away with the domesticity of the three panel strip and instead sets her characters loose upon a visual subconsciousness.

Becoming Horses is a collection of work which features nameless characters who have previously appeared in Wallander’s ongoing strip Slowly Dying. These characters seem to exist somewhere between childhood and adulthood, navigating naivety and existentialism in equal measure. They seem aware of the surrealism of the diegesis, and provide some meta commentary on the nature of the always morphing environment in the book’s opening sequence. Nevertheless, they don’t seem daunted by it: they traverse it, negotiating friendships, loneliness and playfulness in the process.

It actually took returning to Lynda Barry’s work for the above review for me to grasp Wallander’s work. That both are interested in collage makes them fit for comparison, but the following quote from Barry’s What It Is is especially illuminating: “At the centre of everything we call ‘the arts,’ and children call ‘play,’ is something which seems somehow alive." Wallander’s work provides an exact example of the “aliveness” that Barry is discussing here. Much like with Barry’s work, that the characters in Horses could be construed as children is not proof of immaturity or frivolousness. To the contrary, the mixed media adventure that this book provides is a very serious and lively demonstration of play. Nicholas Burman