Last column I noted that erstwhile Quietus comics reviewer Jenny Robins had been shortlisted for the Myriad First Graphic Novel competition. This was a while ago, so it’s old news, but great news – she won. Huge congratulations to Jenny. It will almost certainly mean fewer reviews from her here but in 2020 we will get to read her first graphic novel, and I for one can’t wait.

It can’t all be good news, though. In an echo of the gathering of bigoted bellends known as Gamergate, there is now a similar movement calling itself Comicsgate. Rejecting any form of inclusivity while bemoaning the fact that some comics exist that are not written and drawn by white males, they seem to be upset about more mainstream fare than tends to get featured here, but it is nonetheless dispiriting to say the least.

This time we have a new reviewer onboard, Joe Marczynski who reviews The Strange below, and is neither of those things. Now, on to the comics.

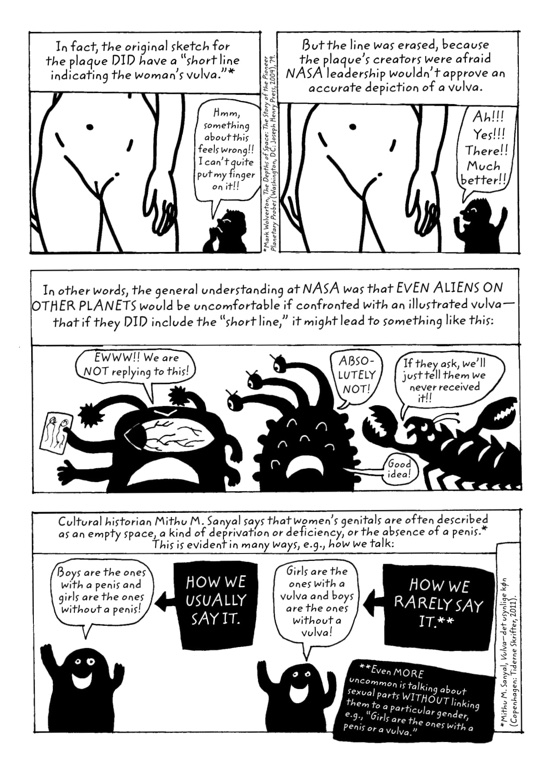

Liv Strömquist – Fruit Of Knowledge

(Virago)

Subtitled The Vulva Vs The Patriarchy, Virago’s first foray into the world of graphic novels is likely to be a huge success. It’s done very well in Sweden, has now been translated into several other languages and was picked up by Fantagraphics in North America, all favourable signs.

Beginning with a chapter about men who have been too interested in the female genitalia, Strömquist selects seven men (which perhaps seems a conservative number, but this is not a book about men, so that’s fine) who have had an overwhelmingly negative impact on women as a whole and some women very specifically. I was unaware that the founder of Kellogg’s was also a doctor who prescribed the application of pure carbolic acid to the clitoris for treatment of the illness of masturbation, and this is the guy who is at number seven on the list. As for number six and onwards…

Strömquist offers us an enlightening look at how views on the relationships between male and female genders, and the characteristics of the sexes, have reversed over time, with a lusty sex drive first seen as a female trait then instead as male. Regardless of changes, however, female sexuality has always been defined in the context of male sexuality rather than in its own right. Female genitalia has typically been depicted as an absence, defined in relation to the penis, and the impact this has on societal perception is substantial. This is an impeccably researched and copiously footnoted work, refreshing in this era of insubstantial academic discourse. It is also enormously funny, with a deadpan sense of humour evident throughout, such as when comparing differing attitudes to female and male orgasms, or how NASA removed all representation of the vulva from the images of humans they sent into space.

One detail I particularly loved was the way that patriarchal figures from different eras are drawn, so one panel might feature a priest who conveniently knows exactly what god wants (spoiler alert – god favours the men), and then the next panel features a scientist with the same face (spoiler alert – his research favours men). It’s a little thing, but very much adds to the impact.

Almost every page is so brilliantly and wittily written and unarguably righteous that it is constantly tempting to show the book to the nearest person. This is a sure sign that this is a work of unusual excellence. Buy two copies – one to read and keep and one to lend out – and make peace with the idea that you may need to get more in time. Pete Redrup

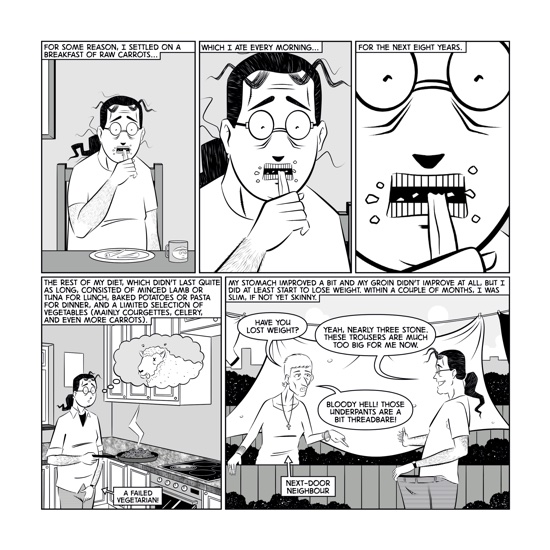

Robert Wells – Back, Sack & Crack (& Brain)

(Robinson)

Back, Sack & Crack (& Brain) could be shoehorned into the graphic medicine genre of comics. However, unlike many examples, this book is very much played for laughs. Wells suffers from chronic pain, very much centred around his testicles and later, his back. This is the story of his attempts to get a diagnosis other than hypochondriac out of a seemingly infinite series of medical professionals over more than two decades.

It’s hard to convey just how funny this is. Wells is a master of comic timing, scattering punchlines like dandruff falling from a geography teacher’s hair. After a procedure for a testicular torsion (which may or may not have been necessary), he describes waking in a glorious morphine haze, only peripherally concerned about his post-operation testicle count. As doctor after doctor fail to find the cause of his pain, he becomes increasingly paranoid about being labelled a hypochondriac, and is perhaps the only person ever to be disappointed not to have Crohn’s Disease.

Wells is not terribly complimentary about healthcare professionals – it’s unlikely this book will have been used as part of the NHS at 70 celebrations. It must have been incredibly frustrating to go round in circles in the way he describes, and he certainly describes some less than professional bedside manners, including one GP who argued for half an hour about the inappropriateness of an adult reading comics. My only disappointment is that there is no photographic evidence of the priceless succession of terrible haircuts – perhaps this could be added to the about the author page of a future edition. This is one of the funniest comics I’ve read, and is highly recommended. Pete Redrup

Samuel C Williams – Daddy Day

(Good Comics)

Samuel Williams is well known as one of the publishers of Good Comics, but this is the first comic of his I’ve encountered. Daddy Day is about parenting, specifically about what it’s like to only see your kids at weekends after living with them full time. This isn’t a book about how he got there, just about how it is, and in the introduction Williams describes the process of making these strips as a form of therapy that has done its job.

This short comic reads like a stream of consciousness – there’s no overarching narrative here, just moments of solo parenting. Anyone with children will be able to relate to this – we see negotiated bedtime extensions, the way a bed invasion ends up with the abandonment of normal human-bed alignment protocols and the pushing of the parent to the edge, the discovery of pockets full of precious artefacts, and the bittersweet calm that descends when children are gone and you are left in their mess.

The book has a variety of art styles, no doubt in part a consequence of Williams writing this book over a period of time. Sometimes we get pencils, sometimes inks, and the colouring is similarly diverse. At once intensely personal and universal, Williams has produced a genuinely heartwarming comic that is very much recommended. Pete Redrup

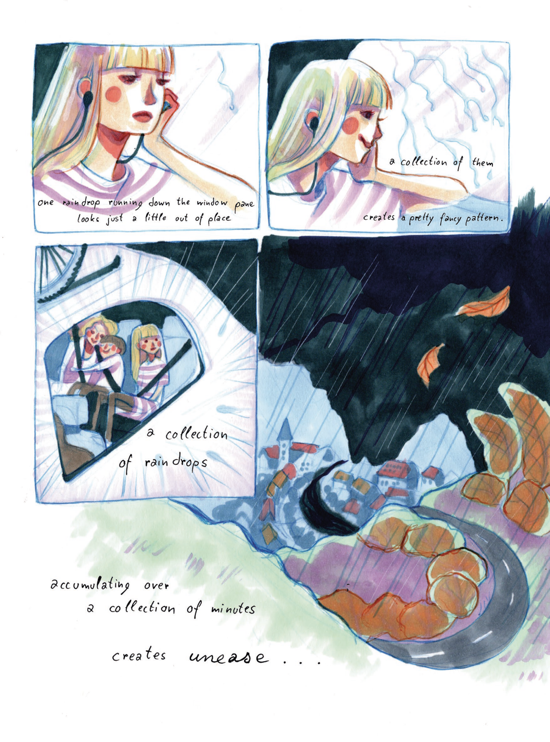

Various – Broken Frontier Small Press Yearbook 2018

(Broken Frontier)

By now, you probably know what you’re getting with one of these Broken Frontier Small Press Yearbooks. There will be longer strips by the previous year’s crop of ‘ones to watch’, and some shorter ones by more familiar names. This time the more established cartoonists include EdieOP, Alex Potts, Till Lukat, Robert Wells and someone called Jenny Robins.

As for the new names, all the work is good as is always the case with Andy Oliver’s selection. Josh Hicks turns in Battery Acid, a slickly drawn ultramodern thriller about a contract killer, one of the best of his pieces I’ve read. The real standout, however, is by Anja Uhren. A Collection Of Raindrops bursts from the page, an uplifting story of human kindness in the face of holiday misadventure. Thoroughly deserving of the extensive page count it was granted, it’s an exceptionally accomplished work. Different colour schemes on almost every page perfectly convey the transformations of mood as the setting changes, and the overall impact is quite lovely.

With anthologies, there’s always a danger that no matter how good the individual pieces are, the individual brevity leads to a lack of distinctive character. This is absolutely not the case here – the overall consistency and the inclusion of a few longer pieces produce a more satisfying result, and the winning format of new talent and older names once again makes this an essential purchase for fans of small press comics. Pete Redrup

John Harris Dunning & Michael Kennedy – Tumult

(SelfMadeHero)

Housed in a striking pink hardcover, Tumult is a stylish noir written by John Michael Harris and drawn by relative newcomer Michael Kennedy. Protagonist Adam appears to have a pretty ideal life, and in classic narrative style sabotages this on multiple levels as he is drawn into the mysterious life of a woman he meets at a party. An amateur tarot reading at the start of the book takes on a greater significance as it provides the structure for what follows, a path of self-destruction of his relationship, his career and his sobriety.

Dunning narrates in staccato bursts, with droll one-liners clearly marking out the noir territory this story explores. Kennedy’s artwork is a perfect match, panels of head-on images glancing straight ahead or to the side confronting the reader, daring us to look away. The colour palette changes constantly, to great effect, always maintaining the mysterious tone. It’s a cineliterate book, with recurring analyses of 80s action blockbusters providing meaningful interludes between different sections, an appealing touch.

By the end the excellent cover’s meaning is quite clear. The genre pretty much requires a slightly expository ending but we’re still left with enough to chew on. Dunning and Kennedy make an excellent pairing, text and pictures in icy harmony, and this is very much recommended for fans of psychological thrillers and classic noir. Pete Redrup

Lottie Pencheon – Summer Break

(Short Box)

Sometimes you only have to read a few pages of a comic to know it is great work. With simple shapes and subtle hand shaded tones, Pencheon manages to absolutely evoke a reality that does not feel right as she explores the story of her own mental health diagnosis during a trip with her family. Her use of the comic form is deft and efficient in its individuality, the use of squiggles and offset shapes positioned with a precision which belies the seemingly childlike style (there’s no denying it’s very cute). These formidable skills of visual communication are put to work in this recent Short Box offering to tell a deeply personal and massively relevant and relatable story. “Not so far from where you are is a place just like this place, except things are slightly off, a little to the left”. As Lottie goes about her life, trying to act like everything is normal and figure out what is going wrong, her friends and family are full of ideas and suggestions.

I say this is relatable, and it really is, but part of why is this human tendency that we have to try and frame others experiences through our own. Maybe that’s why we can tell and enjoy stories, and help each other out with empathy, but it gives us an illusion of understanding that is not always helpful. Lottie doesn’t know what is happening to her, and her journey through clumsy misdiagnosis via advice, research, medical professionals et al is one that is all too familiar, even if her specific experience is not. The love that shines through this book is the counterpoint to that, the mundane beauty of the world and the interaction of people is a constant companion to the internal story going on in Lottie’s brain. If you see this as a work of graphic medicine it’s a great reminder to pay attention when things don’t feel right, even if it does turn out to be simple or small, it could be something you need help with. As a piece of comic art it is a testament to the power of the form to evoke feeling and experience with charm and efficiency. Jenny Robins

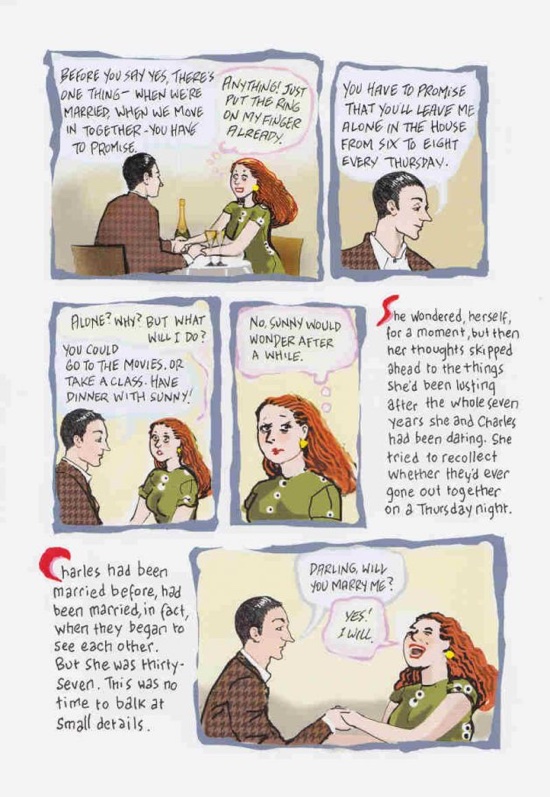

Audrey Niffenegger and Eddie Campbell – Bizarre Romance

(Jonathan Cape)

Bizarre Romance compiles a broad range of narratives and bits and pieces created collaboratively by an undoubtedly illustrious couple. While it is also undoubtedly true that Eddie Campbell made the incorrect life choice in deciding to switch to digital art, this does not stand in the way of this being a truly wonderful book, and well worth gritting your teeth through the occasional page where this is without doubt. I would recommend taking your time with Bizarre Romance, give yourself the chance to luxuriate in each piece in turn. Nifenegger’s prose is straightforward and magical – just the right mix of the two, but knowing this is a collaborative work between a married couple brings an extra edge of magic to the stories. They are far from schmaltzy, but rather bittersweet, pragmatic and tender. Both creators have a playful but thorough grasp of the potential of the comic book form, which is deployed fully in some sections, while other sections lean to sparsely illustrated prose. Meeting each story on its own terms though is rewarded with some perfect moments of oddity.

I now have to do that thing you do when you review a compilation and list some of the things to demonstrate the diversity of the contents: Historical figures are reimagined, new angles on being spirited away by the fairies are explored, there is a love letter to one lost in the flood, and two very different takes on death and cats, angels infest an attic, a century of loneliness passes in a post-modern fairy-tale, every boyfriend is dissected and reassembled. Love is ostensibly the theme, and it is here in many colours but usually burning vividly around the edges of what is not said, what is not shown. That same slow aching burn you feel around your heart just before you mess up trying to explain it by saying you love someone. Jenny Robins

Jérôme Ruillier – The Strange

(Drawn & Quarterly)

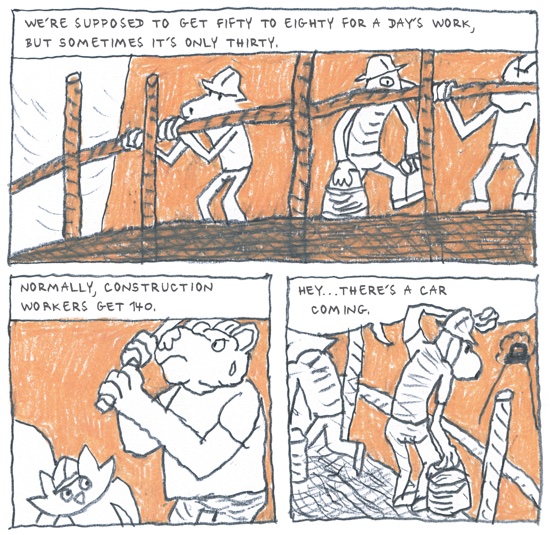

The first Jérôme Ruillier release translated into English, The Strange charts the tragic journey of a nameless, anthropomorphic dog as he attempts to build a new life as an undocumented immigrant in France.

After travelling from an unnamed country using a fixer, the protagonist faces a seemingly endless sequence of trials and tribulations owed to nosey neighbours, exploitative bosses and Kafkaesque French bureaucracy. The fragile nature of his position is exposed immediately upon arrival, as a well-meaning stranger calls over a policeman to help with directions, forcing the terrified protagonist to slip away in the urban sprawl.

Based on real immigrant accounts provided by workers of activist group Réseau Education Sans Frontières (Education Network Without Borders), The Strange blurs the line between fiction and nonfiction, creating an allegory for the desperate situation many immigrants face in the pursuit of new existence in the West.

This kaleidoscopic view of immigration spans a diverse range of perspectives, from callous politicians and their policeman enforcers to sympathetic activists offering respite from predatory landlords. Even passing birds and household pets are given voice, but never the protagonist. Ruillier’s hunched, awkward protagonist speaks only in indecipherable symbols, mirroring the disorienting and isolating effect of his inability to communicate in this new world.

Each chapter is punctuated with real life quotes from right wing mouthpieces, including Nicolas Sarkozy and Marine Le Pen. The inclusion of these quotes describing immigrants as ‘gangs of thugs’ with ‘ways of life very different to our own’ make grim reading among the backdrop of Ruillier’s cast of innocent looking animals, acting as a stark reminder of the fascist undertones increasingly precedent in modern politics.

Depicted in frantic pencil sketches complemented with reds, yellows and browns, Ruillier’s urgent, surreal artwork gives each panel a feeling of unrest, painting a chaotic world that keeps the plot lurching forward to its heart-breaking conclusion. Affecting and poignant, The Strange is a deftly told exploration of the struggle facing undocumented immigrants at the hands of a hostile European state. Joe Marczynski