This introduction is going to be out of date by the time I’ve finished typing it, let alone when you read it, and I’m too busy encouraging my children to pick school work over squabbling to stay on top of all the comics news on Twitter. The pace of change is bewildering, a microcosm of society at large, with shops moving from being open to mail order only to completely shut in a few days, and creators anxious about their income.

The sort of comics we cover in Behold! don’t tend to make anyone rich, and most artists are freelancers relying on other work such as illustration, much of which has dried up. So far there has been little government support for the self-employed. I think the most important point to make is that the comics industry as a whole is terribly threatened by Covid-19 and if there to be something left we need to support in whatever ways we can.

If you have a local comics shop and they are still doing mail order, please support them. If your favourite publisher or creator sells online and you can afford to, buy something. Obviously digital copies work nicely from the social distancing perspective.

Some very generous publishers are offering free downloads of some of their titles to help those stuck at home without money to spare. Just to highlight a couple, the lovely folks at Good Comics have a free bundle including some excellent titles we’ve reviewed here, and the consistently brilliant ShortBox has made Emily Carroll’s Beneath The Dead Oak Tree available for free (with tips appreciated) with more promised soon. I’ve also seen many creators making similar offers – too many to name.

I’m barely scratching the surface here – check Twitter and of course Broken Frontier for the latest picture.

Finally, we welcome a new writer to the Behold! team, Nicholas Burman, with a number of his reviews included this month.

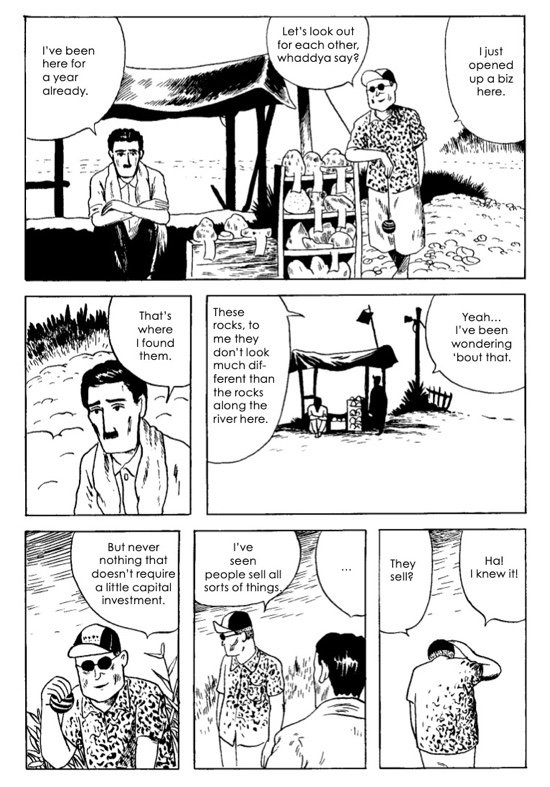

Yoshiharu Tsuge – The Man Without Talent

(New York Review Comics)

A cult manga artist in Japan, Yoshiharu Tsuge is less well known in the English speaking world. The fact that he has published nothing since the late 1980s will not have helped, but the main reason is undoubtedly a lack of translated work. 2020 looks set to be the year that changes; New York Review Comics’ edition of The Man Without Talent is his first full-length book to be produced in English, and Drawn & Quarterly have a collection coming later in the year.

The translation is by Ryan Holmberg, who also writes a typically erudite introduction, sketching out the artist’s career and identifying the points of intersection between the semi autobiographical comics and his life. The Man Without Talent is an example of the "I-novel" (shishōsetsu), which Holmberg describes as "a genre of putatively autobiographical fiction, popular in Japan since the early twentieth century, that typically swells on the writer/protagonist’s struggles with poverty and artistic creation and their less-than-admirable interactions with the opposite sex."

Sukezō is an unsuccessful man whose many failures include being a comics artist. He has now resorted to selling stones, in theory at least; he’s yet to make a sale two years into this career change. As he and his wife argue, their child wheezes on the floor, presumably as his father is too poor to buy the medicine his asthma needs. With downcast eyes and posture to match, Sukezō weathers his wife’s disappointment as best he can. Several of the chapters end with his son appearing to tell him it’s time to come home now, a reversal of what we might expect, indicating just who the child is here.

As the book progresses Sukezō’s clothes become increasingly threadbare, his lack of success impacting upon the wellbeing of the whole family. Tsuge introduces us to a cast of similarly ill-starred men with struggling businesses, nostalgic for former glories. Success is only in the past, for Sukezō and his acquaintances, and the melancholy, mediative tone persists to the end. Beautifully drawn and shaded, frequently matched with poetic writing, this is an exceptional introduction to a master cartoonist. Pete Redrup

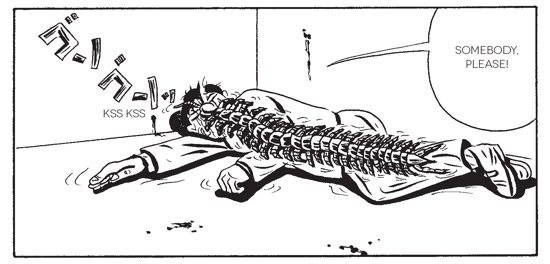

Ebisu Yoshikazu – The Pits Of Hell

(Breakdown Press)

The Pits Of Hell is this month’s second collection of obscure, decades-old manga translated and introduced by the venerable Ryan Holmberg. The differences in the cover art certainly let us know what differences to expect – no matter where we start, we usually end up in nightmarish ultraviolence by the end of the stories here. Ebisu’s brief introduction describes his drawing as atrocious and generally has the air of a successful older person asked to reflect on their teenage outpourings, but then anyone who looks at this cover and opens this book expecting a staid account of day to day Japanese life from the 1970s deserves the surprise they will get. We are not here for the verisimilitude but for the social commentary, and Ebisu does not disappoint.

As is traditional for retrospectives such as this, we are presented with three essays at the front of the book, including a lengthy Holmberg piece and the short, embarrassed retrospective for each manga by Ebisu. Manga was not the sole career path followed by the artist, described as a ‘talent’, the sort of light entertainer who appeared on game shows and the like. Holmberg begins with an account of a gambling arrest, resulting in the cancellation of 22 TV contracts but not harming Ebisu’s manga work, as this was decidedly less mainstream. Obsessive gamblers are found throughout this collection, and heavy gambling remains a lifelong obsession, apparently his only vice. The media work returned and Holmberg notes that he is a millionaire, perhaps a singular quality among the artists featured in this column.

Inspired by Tsuge Yoshiharu, Ebisu’s work is described as heta-uma, the bad-good genre. He has splendid taste in titles, with the first story being Teachers Dammned To The Pits Of Hell. A boring, uninspiring teacher, the first of many perpetually sweating protagonists, finally snaps and takes his frustrations out on a pupil. A prolonged bout of violence ends with a decapitation and the teacher finally gets the attention of his class. The book constantly revels in fantasies of violent solutions to life’s problems. We learn from the essays that Ebisu once worked as a sign fitter, and this becomes the subject of another piece here, where an abusive boss pushes his junior too far; the unhappy worker can only take so much abuse before he erupts into ultraviolence. There is a strong sense here that the oppressed worker must be treated with dignity, although we also get bosses brutally beating their employees for being lazy.

The Pits Of Hell is never dull, the simplistic but stylised and direct images working well with the satire, social commentary and dream-like narrative turns. As ever, the main essay does an expert job of contextualising the work and Breakdown’s design only enhances the appeal. This is a fascinating collection of deeply unusual manga. Pete Redrup

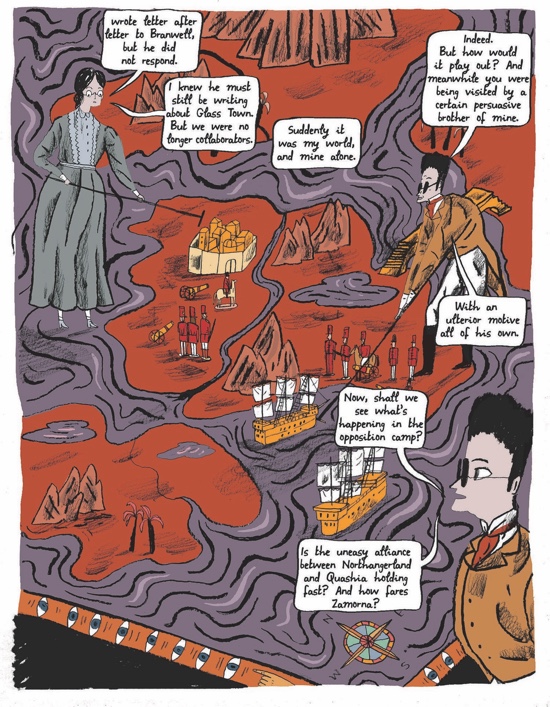

Isabel Greenberg, Glass Town

(Jonathan Cape)

Isabel Greenberg has an uncanny gift for the tone of storytelling that makes you feel like you’re tucked up safe in bed being told a story by someone with a twinkle in their eye. To take on the voices of some of the most celebrated writers in literary history in her new graphic novel, she forges this gift into some contorted framing devices that at first feel a little disjointed, but pay off beautifully as the book unfolds. When it comes to stories within stories within stories we couldn’t be in better hands.

Glass Town itself is a real imagined place, which is to say, it really was imagined by the Brontë sisters and brother, back when they were growing up and inspiring each other. Charlotte Brontë is the protagonist of the book, accompanied by her creation/alter ego Charles and we first meet her having recently lost her siblings Branwell, Emily and Anne and living in a grey, grief stricken version of their childhood home upon the moors in Haworth. They look back on both the time the child authors spent together and apart at various schools, and most specifically at the stories they told and wrote together of their imagined kingdoms.

Each layer of the story has its own colour scheme but the art throughout is consistently inventive and engaging, playing with the overlapping of reality and fantasy. The inhabitants of Glass Town, much like the Brontë siblings, aren’t often very nice to each other, their foundations built on both the joys and tensions of a family growing up so isolated and engaged in "scribblemania". The book works on many levels but perhaps the most powerful is the feeling of a child’s imagination at work within the heart and mind of a grown genius in grief. Jenny Robins

Seasonal Shift – Lala Albert

(Breakdown Press)

A collection of highly imaginative freeform comics, Seasonal Shift is the latest release from Lala Albert, published by indie stalwarts Breakdown Press. With exceptionally graphic (and occasionally interspecies) sex scenes, there’s a loose science fiction theme running throughout this unusual collection. A woman mysteriously finds bees in her hair, culminating in a sticky end to an intimate moment, a casual sexual liaison on an intergalactic journey takes a dark turn, and the plastic in our oceans results in a disturbing body horror episode.

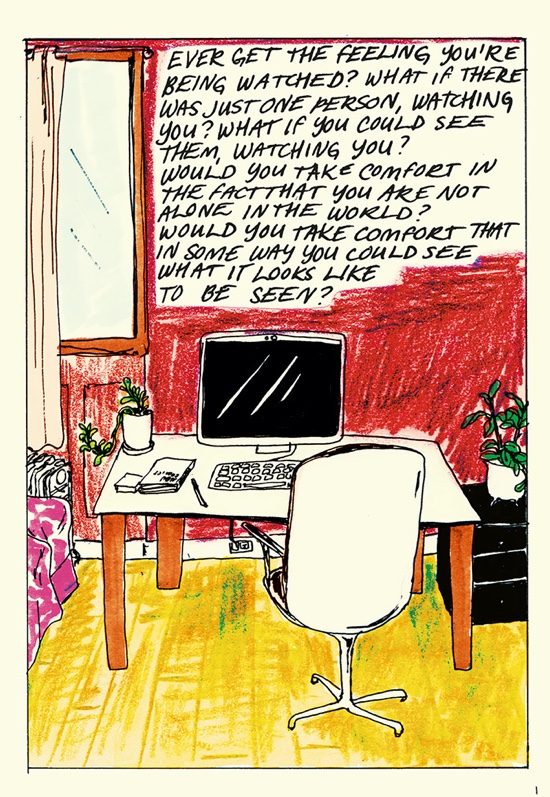

In case it’s not clear from the above, this isn’t a traditional space men and aliens sci-fi romp. A standout early story is reminiscent of Black Mirror, where an app that allows online stalking through a user’s webcam brings two loners together. Despite Albert’s obvious proclivity for technology and the future, in the introductory interview at the start of the book, she confesses she’s not really a fan of science fiction (Star Trek aside). This is a strength of her work – all of her stories are free of the stereotypes that plague the genre.

The longest story in this collection is a wordless journey through beautifully rendered wildlife, following a couple of woodland pixies. The final section is a sort of visual poem, with surreal imagery interwoven with sparing lines of elegant prose.

Albert explores a range of art styles and mediums, with scratchy pen drawings, vibrant watercolours and even expressive pencil crayons present. This DIY aesthetic is perhaps because the majority of these stories were originally self-published from 2013 to 2019, so Seasonal Shift offers a great opportunity to snag a healthy chunk of Albert’s hard to find back catalogue. Joe Marczynski

Michael DeForge – Familiar Face

(Drawn & Quarterly)

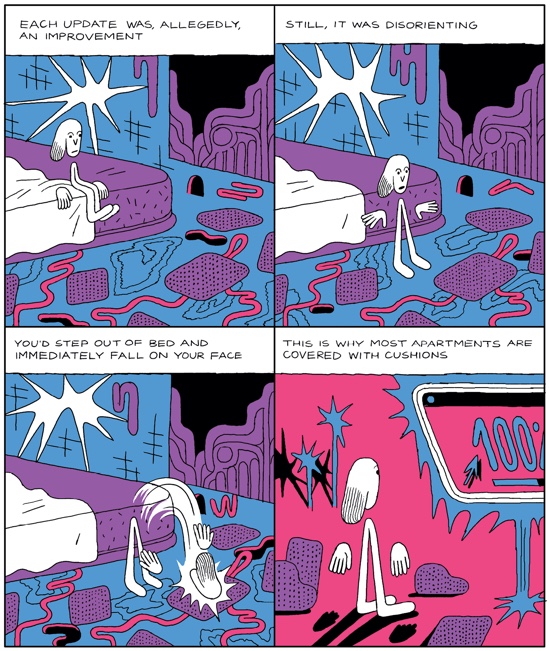

Familiar Face is an intimate address told in the past tense, a technique which tends to signal that things didn’t work out the way the narrator hoped. The book’s opening sequence introduces us to a world populated by Play-Doh cyborgs and personified abstract shapes. Our protagonist’s urban surroundings are always subject to change thanks to what is officially referenced to as "optimisation." It’s not quite a dystopia in the traditional sense, however, more like a world with a different logic altogether. The visual track portrays it as one full of colour, and dominated by screens and bewildering entanglements of infrastructure.

The plot of the book is mostly woven around our protagonist dealing with her girlfriend’s unannounced departure. This shock separation is the event around which our narrator-in-the-future is attempting to come to terms with. We are gifted anecdotes of shy, quiet evenings between the pair, and recollections of a couple attempting to re-learn each other following every time the state issues their bodies "fixes, upgrades, refinement, additions, and subtractions" that render them unrecognisable. The fantastical diegesis DeForge creates allows for these technofascistic intrusions on personal lives to become metaphors for the way in which all types of partnerships, as friends and lovers grow and develop, make room for each other.

Our protagonist’s day job is to listen, with no real purpose, to complaints filed with the authorities. It is a reckoning with this work that leads the way for Face‘s abstract and surrealist finale. One of my favourite parts of the book occurs in the first act. It is a splash page on which the couple, pre-split, are being drawn together, a depiction informed by subconscious and dream-like visions of coupledom. The two bodies, disjointed and impossible in the reader’s world, curve into each other and appear to bend their surroundings to their embrace. It’s a passionate visual depiction of companionship in a work with ample visual flair and a story that, despite the past tense pessimism, does conclude with a romantic glimpse of hope. Nicholas Burman

Hamishi Farah – Airport Love Theme

(Book Works)

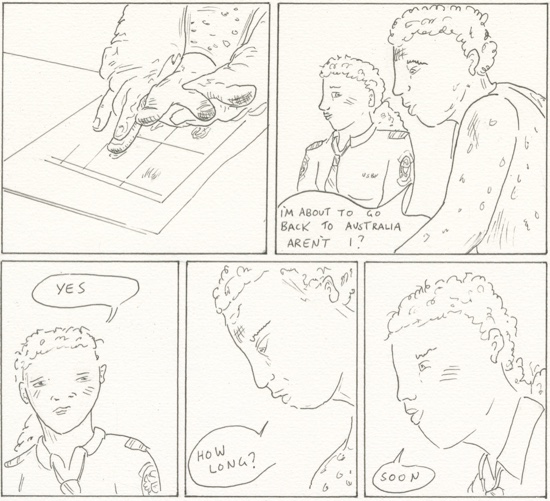

Airport Love Theme takes us into a darkly comedic Kafkaesque world of automation and authoritative voices. Farah portrays a liminal space where border security can’t remember refusing someone entry to a country two times previously but a detainees’ phone remembers the WiFi password. The book is based on the artist’s experience of being unfairly detained at LAX in 2016. Along with the other detainees, Farah awaits their fate as they’re left to grow agitated and watch Coming to America. As well as the artist’s avatar "I" telling the story, the captions also refer to "our artist" in the third person, reinforcing the sense of self doubt that the process of the type of interrogation depicted seems to create.

The story is split between "our artist’s" POV and interactions between the border patrol officers. We are also brought into the mind of an officer called Snyder, who is constantly thinking about a story he’s writing. He garners inspiration from sources as diverse as his pet fish to sexual fantasies involving a female co-worker called Rice. We see one sequence literally through Snyder’s eyes, as he waits for the artist to relieve themselves in the toilet; this strip is, for reasons I still can’t explain, the funniest two panel repetition I’ve ever read, though I admit it may not have been funny at the time.

Airport‘s mise-en-scène is drawn in minimalist, geometric shapes that recreate that airless atmosphere that airports produce. The work is ostensibly a realist, autobiographical narrative, yet there’s a sequence in the third act which unravels what’s preceded it in an explosion of sexually charged fantasy and warped page layouts. The book does a good job of highlighting the inhumanity, and also the pure stupidity, of hostile environments. Its piercing of realism with sparks of surrealism and narrative trickery is what makes Airport Love Theme a singular portrayal of the intersecting relationships and experiences of helplessness, state power, revolt, racist perceptions and bureaucratic skulduggery. Nicholas Burman

Douglas Noble – Other Horrible Folk

(Strip For Me)

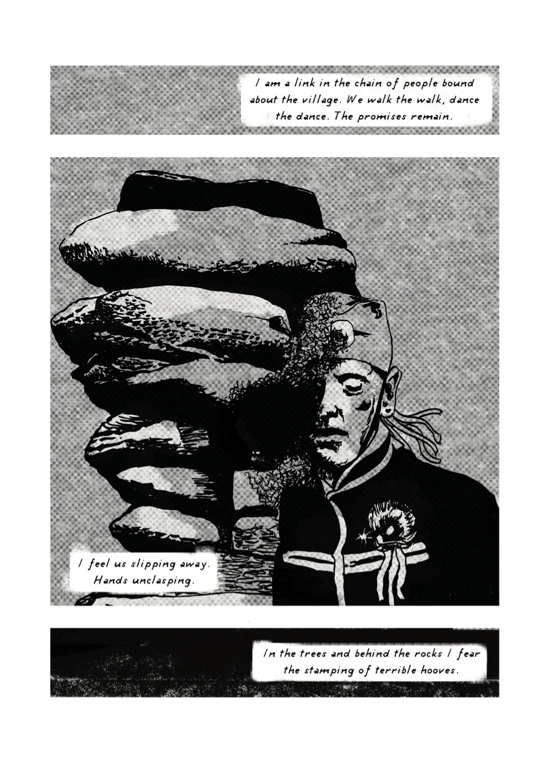

This is the third instalment of a series wedded to the intersection between British pop culture and folklore. Through producing adaptations of such culture through comics, Noble has fashioned an intriguing niche for himself. From the poetic Counting Stones: A Hymn Of Castlerigg to anthology of strangeness Jazz Creepers, his work is perfect for readers who also enjoy the disquieting world of The Wicker Man, for example. This instalment’s narrative is a collage of two sources, Ralph Whitlock’s study of pre-Christian traditions on the British Isles and documentaries that were part of the BFI’s Here’s A Health To The Barley Mow DVD collection.

Noble’s thick and often scruffy pen produces a fittingly earthy portrayal of rural and small town Britain. His use of the halftone technique, that colours many of the panels in a polkadot grey, calls to mind the damp atmosphere that is something of a permanent characteristic of Britain’s coastal regions. There is great pleasure on show in the depictions of pagan and animistic monuments that punctuate the landscape. Noble’s singular approach to panel divisions is notable throughout, via which time and space become as disjointed and magical as the stories being told, which themselves are devised from those monuments which create a bridge between tradition and contemporary life.

Noble’s text is a pleasure to read. I don’t know how much here is original and how much is lifted from sources, but to reproduce the rhythms and cadences of colloquial speech, either after transcription or through imagination, is no mean feat. It is through the combination of realistic speech patterns and the tactile visual depiction that the characters in Other seem more than ink-drawn representations. Listening is a recurrent theme: to the sound of the environment, and to ancestors and ancient rhythms. Noble appears to be the visual equivalent of one of his characters, who "wrote music based on the shape of the hills, the rustle of the trees, the angry cliffs. Someone seeking tunes waiting for new ears to hear them." Nicholas Burman

Clément Vuillier – L’Année de la Comète

(Éditions 2024)

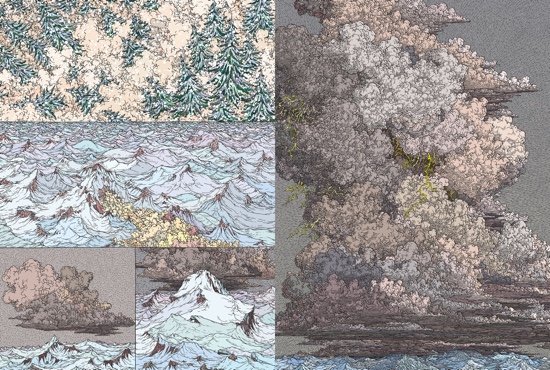

One likely reason why those of us living under the Anglosphere’s hegemony may not have heard about Clément Vuillier’s 2019 book is because it’s published under a French title and through independent French publishers Éditions 2024. Fear not, monolinguists, or those, like me, who spectacularly failed their French GCSE, because L’Année de la Comète [The Year of the Comet] is a silent apocalyptic adventure. The book’s large format (28.5cm x 38.2cm) and heavy paper results in a sense of epic that befits Vuillier’s story. A fiery comet is plummeting towards an unspecified planet that is characterised by glaciers, sharp mountain tops and violent seas. As the comet gets ever closer the planet fights back; from beneath the ground of a dense, tropical forest fantastical bursts of energy spurt upwards in an attempt to reverse the comet’s trajectory. The narrative ends where it started: gazing at pin pricks of light in an otherwise seemingly empty sky.

The various geographies of the planet, the sky and the comet are personified through their different colour schemes. Vuillier’s depiction of nature, and of waves especially, calls to mind Katsushika Hokusai’s ability to depict geological events as having agency and purpose. Some pages are divided with hairline gutters, but many are splash pages, while others explode across a double page spread. While the narrative’s perspective becomes evermore overwhelmed with the gigantic nature of the nonhuman protagonists, the comic nearly transforms into an abstract work, as shapes and colours begin to become dedifferentiated from the objects they’re associated with.

L’Année provides a sense of impending doom and unknowable forces similar to that found in Martin Vaugh-James’ seminal comic The Cage. Vuillier also shares with Vaugh-James a dedication to depicting objects in an uncanny world with mathematical precision. He is less interested in subverting perspectives than Vaughn-James was, and is instead dedicated to experimenting with scale and expanding the possibilities of what can be seen to fit into the humble comics panel. Superbly detailed pen work à la Mobius is present throughout, which means that even as chaos ensues the action retains clarity, and as we focus in on the various elements in the story the interlocking shapes result in the appearance of bizarre and hallucinogenic puzzles. Simultaneously an artistic and theoretical exploration of the relationship between shape, colour and spatial arrangement, L’Année is an adventure not only through an anthropomorphic geography but also in what exactly it is that comics are. The world doesn’t end, and, thankfully, the fact that 2019 is already long gone doesn’t mean you have to miss this gem. Nicholas Burman