The final comics column of the year is upon us, and so thoughts turn to lists of great things. For me, the finest books of 2019 are Chris Ware’s Rusty Brown (Jonathan Cape) and Kevin Huizenga’s The River At Night (Drawn & Quarterly), both reviewed below. I also loved Luke Healy’s travelogue Americana (Nobrow), his most personal and accomplished work to date. Jayde Perkin’s self-published I’m Not Ready is another brilliant comic that is both personal and moving. Anders Nilsen’s Tongues #2 (Self-published) continues the mesmerising setup of his retelling of Prometheus, making spectacular use of large format layouts.

Drawn & Quarterly had another excellent year, with my other standouts being Eleanor Davis’ The Hard Tomorrow (also reviewed below), Linda Barry’s Making Comics, a book to draw out the inner comic artist in all of us through drawing exercises, and Ebony Flowers’ Hot Comb, a collection of short stories that continue to resonate long after they are finished. Avery Hill continued their extremely strong run with many great books, including Mimi And The Wolves Volume 1 by Alabaster Pizzo and Internet Crusader from George Wylesol, both of which also get reviews this time. Simon Hanselmann’s Bad Gateway (Fantagraphics) delivered another brilliantly appalling episode in the lives of Megg and Mogg. Finally, Ian Williams’ The Lady Doctor (Myriad) is a nuanced, warm and empathetic book that I enjoyed immensely. Save our NHS. Pete Redrup

2019 has been another great year for me acquiring comics and not necessarily getting time to read them. I even signed up for some monthlies, including BOOM Studios’ Something Is Killing The Children by James Tynion IV, Werther Dell’Edera and Miquel Muerto. Three issues in I’m really enjoying that so that’s #1 of my top five – a well-paced and contemporary feeling little teen horror story. #2 and #3 are going to be no surprise as things I reviewed rhapsodically here – Gareth Hopkins’ Petrichor from Good Comics and James Stokoe’s – Sobek from Shortbox. Both roller-coaster reads for entirely different reasons. #4 is a SelfMadeHero translation of a French graphic history of typography – more fun than that sounds and with a wealth of varied visuals to complement the learning, ABC Of Typography by David Rault is well worth picking up. My final pick of the year is a long awaited collection and completion of the short stories of Faraway Hills that have been appearing over the years in Soaring Penguin’s Meanwhile… anthologies. The Bad Bad Place by David Hine and Mark Stafford has just come out and is appropriately horrific and brilliant, riffing on genre tropes but ultimately exploring the absurdity of human desire and deserving. Jenny Robins

My favourite book of the year has to be King Of King Court by Travis Dandro. An unflinching look at the complex figure of his father, Dandro’s memoir is told without self-pity or solipsism, instead with a brutal honesty that lays bare the wounds of a traumatic adolescence. Incredibly self-aware storytelling that makes me excited to see what he creates next.

Not a single book, so cheating a little, but the continuation of David Lapham’s Stray Bullets: Sunshine And Roses has been consistently fantastic. I’m a huge fan of this cult crime series and was elated when he finally finished the original story arc (there was an incredible nine-year hiatus between the second the last and final issues). These new collections have maintained the impeccable standard of the original and Lapham’s moody, grimy artwork is as powerful as ever.

Another favourite is Adrian Tomine’s short comic Intruders, released as part of Faber and Faber’s new Faber Stories collection. A haunting tale of post-traumatic stress told with Tomine’s signature realist style, it’s great to re-read this story originally included in his (brilliant) 2015 release Killing and Dying. It’s novel to see a comic included alongside serious literary works, and a clear indication of how important artists like Tomine are to the medium. Joe Marczynski

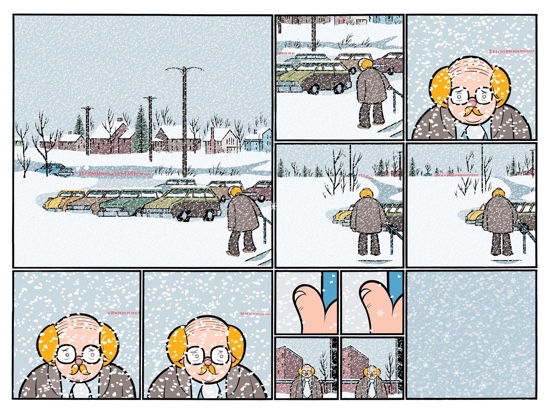

Chris Ware – Rusty Brown

(Jonathan Cape)

Chris Ware’s new book may be called Rusty Brown after one of its characters, but the titular young boy is barely given a supporting role, in this volume at least. It features stories from Ware’s ongoing Acme Novelty Library series plus a largely unpublished one, and we learn much more about the boy’s father, bully and third grade teacher than we do about him. Readers of his long-standing series will know that we will eventually get to meet Rusty Brown as an adult, but not today.

The book begins with a wonderfully evocative section, a 70s winter school day. Rusty and his father William are getting ready for school in the top three quarters of each page while two other children feature in a story told in much smaller panels along the bottom. Chalky White and his sister Alison are preparing for their first day at a new school, and this pair are also destined for greater prominence in the next volume. Ware shows his narrative and visual precision as the threads unfold, finally converging after 30 or so pages as Mr Brown and the White children occupy the same space briefly before continuing on their own paths. The art teacher at this school is called Chris Ware, and what we are to make of this character is unclear. In his endnotes and interviews Ware has a tendency to be self-deprecating beyond what one might consider to be a theoretical maximum, but even by his own standards this character seems designed to elicit a very low opinion of the author as he peers up the skirts of his female students and spends lunch breaks smoking pot in the back of student Jordan Lint’s car.

The next portion is devoted to William Brown, essentially a Talking Heads-like exploration of ‘how did I get here?’, with here being a bald, overweight, middle aged English teacher disappointed in every aspect of his life including his marriage and son. Ware presents us with a chilling sci-fi story Brown wrote when younger, a significant moment for him when it was published in an anthology and nominated for an award but ultimately one which contributes to his present feeling of a meaningless existence. This is followed with a sad narration of an infatuation with a woman he met at his first job, most definitely not the future Mrs Brown. This relationship is unsuccessful in part because it never occurs to him that she might not feel the same things he does, which, doubtless without coincidence, is one of the problems the protagonist of his sci fi story also has. One page features 177 tiny panels, offering value for money if not easy reading. These bounce from indignity to humiliation with the woman, via eviction, being fired, meeting and then almost immediately impregnating his future wife, leading back to the present day when he sits in his study masturbating to porn and wiping himself off with sheets of paper pulled from his typewriter. William Brown is not living his best life.

Third is the account of Jordan Lint, bully and stoner thus far in this book, and of course, another sad and pitiful tale. The opening is a perfect example of Ware’s brilliant compositions, from the point of view of Lint from newborn baby to young child. Within a few pages we’ve seen the world take form, Lint’s father’s racism take root in his consciousness, and then we are at his mother’s funeral, swiftly followed by his father’s wedding. This does not help Lint grow into a well-rounded and happy man. Ware has a real talent for building page layouts that avoid the simple left to right then down a row format; no matter how inventive he is, the page remains easy to follow, the narrative always clear. It’s one of the many things that make his work such a delight to read.

The final part concerns Joanne Cole, a lonely black woman in a very white and noticeably racist city. We see her at various stages of her career at the same school where William Brown teaches, from third grade teacher to assistant principal. Aside from work and family, her main interest is the banjo. She cares for her mother, who lives with her, and has a tense relationship with her sister, and a secret in her past. More so than the rest of the book, this constantly switches between different timelines from her childhood to numerous stages of her career. As we by now expect, this is not an uplifting and joyous tale, as she faces constant prejudice and an emotionally barren personal life.

This is the work of a tremendously gifted cartoonist whose formal brilliance is indisputable, and whose sprawling narratives come to us via endlessly inventive pages. Rusty Brown is another masterpiece from Ware, and is unmissable. Pete Redrup

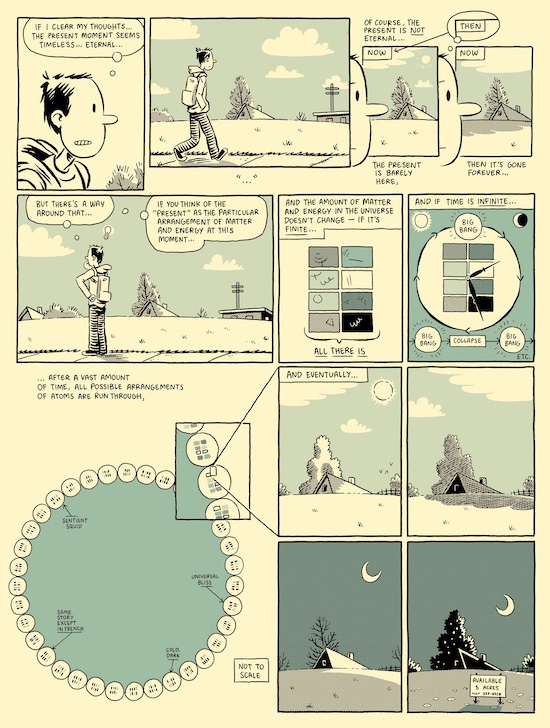

Kevin Huizenga – The River At Night

(Drawn & Quarterly)

The River At Night collects and expands Kevin Huizenga’s long-running Ganges comics in a single beautiful hardback volume that’s a little smaller in format than the six individual issues were. Divided into 19 sections, the third begins with an establishing panel showing that it is far enough into the evening to be fully dark, and we see Glenn Ganges making a pot of coffee from which he proceeds to drink several cups. He’s still on the coffee when his wife Wendy goes to bed, and this ultimately results in a long night of insomnia, the device around which this entire book is fashioned. As he fails to get to sleep his mind wanders and Huizenga uses this to muse about numerous topics from the minutiae of Ganges’ life to space and time itself.

This good natured, charming book is full of endlessly inventive layouts. The first few pages are a perfect illustration of how comics can communicate in a way no other medium can, as we get a philosophical exploration of the infinity of time. Ganges’ mind wanders as he walks to the library, his thoughts becoming ever more tangential until he’s woken from his reverie by a car horn from a former colleague. This thread is picked up a few sections later in the story Pulverize, a brilliant account of the Dotcom era. Glenn is working at a tech company started by a nerd who then brings in a corporate guy to manage it, where the staff all stay in the evenings playing a thinly disguised Quake while pretending to their partners they are working late. It’s an extremely well done piece, capturing the thrills of that sort of game at a time when multiplayer gaming required a local network as for most people, the internet was just too slow, and also skewering the business conventions of that moment in time.

The coffee inflicted insomnia results in endless failed attempts to get to sleep. Glenn gets up and potters about for a while, returning to bed to fail to sleep again. Books are read, including a splendidly oblique philosophical discourse selected for its soporific qualities, which unfortunately turn out to be insufficient in the face of caffeine. There is an aside about just how many books it is reasonable to own based on life expectancy and rate of reading. Another section brings musings on the fragmentary nature of our long and short term memories, with units of time laid out in grids for analysis. Huizenga is adept at moving from the very small – this is a great sandwich – to the very large – how the universe is arranged. There’s a brilliant chapter looking at the life and work of James Hutton, geologist, full of first-class illustration work that brings his ideas to life, and then a moment later Ganges is full of regret for not saying something at a funeral.

Huizenga captures the way the mind can wander off at the least opportune moments, and uses this as a framework to produce one of the most delightful, impressive comics I have ever read, as narratively sophisticated as it is beautifully illustrated. So many strands are pulled together here in a wide ranging but utterly coherent book. Time never moves as slowly as when you can’t sleep, or as quickly as when you are engrossed in poring over these pages. This is an essential purchase. Pete Redrup

Eleanor Davis – The Hard Tomorrow

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Set in an all too believable near future, The Hard Tomorrow is the new book from Eleanor Davis, always a cause for excitement. Hannah is a care worker and activist who would very much like to be pregnant and living in a home rather than the back of a truck. Her partner Johnny is slowly building them a house but has not yet grasped that making progress with this is not entirely compatible with being a full time stoner. They are living in an America that doesn’t seem a huge leap forward from the present, but one where all the changes have been for the worse. Davis’ suggestion for president is at once entirely plausible and utterly horrifying. The societal background is one of state oppression and protests against this. Most protesters are sincere, but there is a masked pair intent on damaging property which then provides the excuse for violent suppression.

Johnny is getting help from his friend Tyler who lives nearby in a place he calls the compound. There’s more than a hint of toxic masculinity about him as he assesses Hannah’s value based on the amount she could deadlift relative to him. Seemly surviving on a diet of energy drinks and eye drops, he’s a paranoid prepper and fervent red piller. Davis doesn’t hold back in depicting his many obnoxious ways, but also presents him in a way that shows a little sympathy – he clearly wants the best for Johnny, even if he doesn’t agree about his friend’s priorities. Her characters are all written in a nuanced way, believably human, fallible and worthy of redemption, and this is what draws us in. Davis is also a very talented illustrator, and the subtleties and complexities of the characters’ feelings are writ large on their faces.

It might seem paradoxical that a book that describes a society in an even worse state than the present can be so full of hope, but this is not about the bad things that others do, but rather the good things that we can do. It’s about making the world a better place – every character in the book is trying to get prepared for the particular future they think is coming, and is treated generously by Davis. What she gives us is a moment in some lives when some things resolve and others are left for us to imagine what comes next. This moment is so brilliantly drawn, the next step from where we are now, a document of recent changes and where they may take us. Pete Redrup

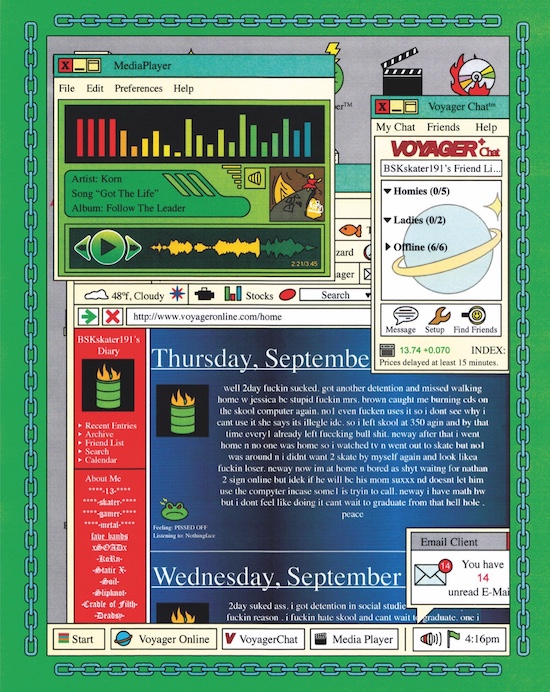

George Wylesol – Internet Crusader

(Avery Hill)

In his memoir Permanent Record Edward Snowden describes the Internet of the 1990s as “for one brief and beautiful stretch of time…made of, by, and for the people. Its purpose was to enlighten, not to monetise, and it was administered more by a provisional cluster of perpetually shifting collective norms than by exploitative, globally enforceable terms of service agreements”. This is pretty much what George Wylesol depicts, an era before it became horribly corporate and designed to spy on the public, when it was just damn weird. Well, this is almost true, except in Internet Crusader Satan has managed to infiltrate the online world and has released a virus that turns people into brain dead Satanic slaves, somewhat diminishing the digital utopia.

Our hero is called BSKskater191 and he is twelve (although naturally his online profile has him claiming early teenage status). The entire comic is experienced through the portal of a Windows 98 era user interface complete with a dialup connection to BSKskater191’s parents’ ISP. The web browser is liberally festooned with so many toolbars that a quarter of the screen is obscured, augmented by numerous popup windows. The early action is a mixture of IMs, personal blog posts and an attempt to get past parental controls and glacial download speeds to access pornography, but before too long a Satanic death cult are wreaking havoc and the only way to stop them is to play Portal2Hell, a colossally violent video game written by god, no less, who might just be plagiarising Doom a little.

Internet Crusader is one of the strangest comics I have read. Visually, it’s a riot, a loving parody of early web user interfaces and subculture, violent Satanic video games and more. The device of framing everything through a screen is not something I’ve seen before in a comic, although it has been done with film, and it leaves so much to the reader’s imagination – we don’t even get to see our hero. If you feel nostalgic for an Internet that is long gone and like the idea that a videogame could save the world, this is the comic for you. Pete Redrup

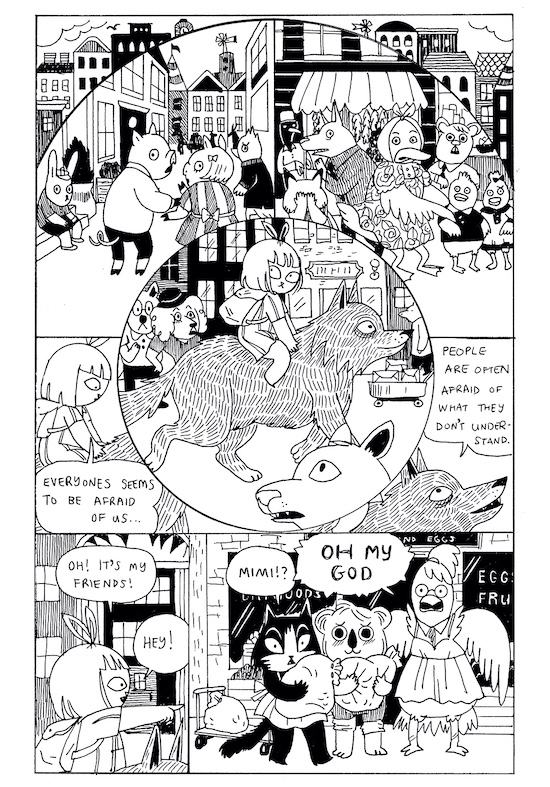

Alabaster Pizzo – Mimi And The Wolves Volume 1

(Avery Hill)

This lovely hardback from Avery Hill collects the first three self-published minis in the series, totalling two hundred pages or thereabouts. Set in and around Hilly City which is inhabited by a variety of animal species in happy coexistence, it’s very cute visually, but thematically less so. Mimi lives a life of quiet domesticity with her partner Bobo in the woods, helping her friend Ceres with her farm and making garlands that everybody seems to love. So far, so whimsical. However, a horrific recurring nightmare sends her on a quest to find its meaning, leading her to the wolves of the title and to Venus, the focus of the dream. Before too long she’s taking part in mysterious rituals, smoking lotus plants and venturing into crystal caves with her new friends. Bobo is not thrilled.

Most of Pizzo’s anthropomorphic creatures are cute but the wolves are wild animals, little troubled by the value of other animal life. In one part Mimi is talking to Ergot the wolf while his mate Ivy hunts. Two young rabbits are playing football while their mother sweeps outside their house, and one kicks the ball into the woods. A few panels later Ivy has eaten one and drops the corpse of the other at Ergot’s feet, who says “Didn’t the family have two kids?”, making it quite clear why the other animals of Hilly City are so wary of wolves. The rabbits were presented to us as loved children and the wolves are aware of this but indifferent – they are just meat. Interestingly enough, Mimi has no reaction to this killing. This segment perfectly illustrates the darkness in this book, and the way characters often behave in unpredictable, mysterious ways.

As Mimi walks through the dark woods there is a sense of latent menace, of being watched by unseen beings. This is similar to how it feels to read this book – the more we learn, the less we are certain about who can be trusted. Pizzo balances the tension between the cute and the terrible in such a way that the overall effect is both compelling and unsettling. Mimi And The Wolves is a fine comic and I am very much ready for a second volume. Pete Redrup

Gareth Brookes – Threadbare

(Self-published)

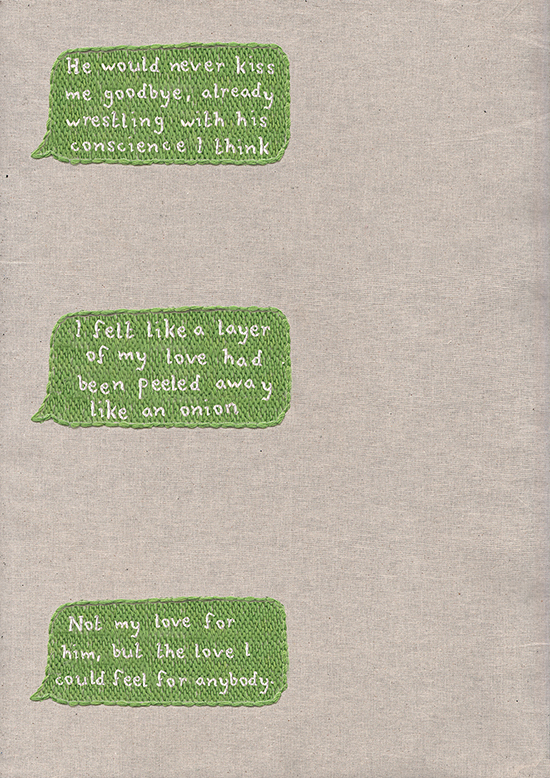

Described as an overheard conversation, embroidered, this unique comic from Gareth Brookes is heavily focused on modern technology, whilst being produced in a much more old fashioned method. The scene is set with a tweet: “Can hear 2 elderly ladies on the train talking very candidly & movingly about the last time they were in love. Hope my pen doesn’t run out.” As well as the text of the conversation he overheard, reformatted in the familiar green and blue speech bubbles of instant messaging, Brookes includes embroidered representations of two couples. The first are in various states of undress and sexual activity, both solo and together, always holding a mobile phone.

A few pages in, we get a very telling image. The woman is standing, hunched, near a side table. From her mouth a thread connects her to the phone sitting on a table; another thread leaves the phone, passes through her hands and ultimately goes nowhere, just left fraying behind her. In the images technology is ever-present, but never unequivocally good – the to-do list found inside the front cover includes not sending drunken messages to L, whomever L might be, and ignoring the man publicly watching porn on his iPad. These goals have been met, but another, don’t tweet anything, has not. We then get the tweet, recounted above, which tells the origin of this comic.

Two double page spreads show the couple alone, masturbating with phones in hand, threads connecting the devices across the pages. The first spread shows the woman with the back of an image of the man, messy with thread. The next double features the front of his image and the back of the embroidered woman, leaving us to speculate about the impact of digital technology on our sexual relationships with others, and of just what and whom we are connecting to. Juxtaposed with the text of the elderly ladies’ conversation, we are left quite clear that relationships have always been fraught with complexity, uncertainty and heartbreak, and that technology might have brought new problems but problems in this space are not a new thing.

As the conversation switches to the second lady telling her story, we get a different couple, again naked but without phones. Unmediated by technology, we see a different form of disconnection. Brookes has created something very unusual here. Every time I’ve read it, my response has been different, with new elements coming to the fore. Subtle, speculative and highly subjective, watching the literal unravelling of the figures while reading the poignant memories is an experience like no other comic I have read. You can buy a copy from his website. Pete Redrup

Chad Bilyeu – Chad In Amsterdam

(Self-published)

Chad Bilyeu is an American writer, illustrator and photographer who moved to Amsterdam a decade or so back to study, and ended up remaining there long after his academic pursuits ended. Originally from Cleveland, he’s taken the same route into comics as that city’s celebrated chronicler, Harvey Pekar, and employs a range of artists to illustrate his autobiographical work, which he sells from his website. Chad In Amsterdam is currently on its third issue, with the next due soon.

Anyone who has spent time in Amsterdam will find much they recognise here – the kind of tourists that congregate in the more notorious parts of the city, the famously direct Dutch (each volume includes a different story titled The Dutch Inquisition which are among the most interesting here, revealing how Bilyeu is perceived in Holland), and how any attempt to speak Dutch is likely to get a reply in flawless English. Not every observation will be welcome in his adopted country – in the second part of Inquisition he suggests that the famous tolerance exhibited in this city dwindles somewhat for those with black or brown skin.

Whilst some of the stories here look deep into Dutch society, others are simply the result of looking out of his window and observing tourists and their encounters with prostitutes. This combination works well – we get a good range of experiences, and the variety in illustrators means that nothing gets stale even if the story is one of the more throwaway ones. At his best, Bilyeu provides a perspective I’ve not seen elsewhere, and these comics are well worth checking out. Pete Redrup

Eric Haven – Cryptoid

(Fantagraphics)

If the concepts of men crossed with dinosaurs, a man shrunk into a gnome and an anthropomorphic eagle fighting Donald Trump appeal, Eric Haven’s screwball collection Cryptoid is the book you’ve been looking for. Filled with punchy, surreal tales, Haven’s latest release from Fantagraphics collects (extremely loosely) connected strips filled with boundless imagination and charming weirdness.

Taking influence from underground comics from the ‘80s and ‘90s, the lead story centres around a ‘The Resister’ – a half eagle half person who emerges from the Washington Monument to take on Donald Trump. Vanquishing a grotesque Steve Bannon in the process – depicted as a demon capable of mutating into a tangle of slime and tentacles (incredibly on the nose perhaps, but a fair depiction of a despicable human), this foray into satire is a welcome change to the often-drab political comics of the modern age. In today’s political climate, it’s tough to be more outrageous or dark than reality, but Haven manages to channel his clear disdain for the current White House premiership into a violent form of wish fulfilment.

The stories in Cryptoid are less focused on narrative than his previous collections, which while zany, usually contained a linear structure. This gives Haven greater opportunity to indulge in bold, colourful artwork – his best to date. Short and sweet, this collection of stories is a good introduction to Haven’s irreverent style – it’s not for everyone – but fans of surrealism will enjoy this strange and imaginative collection. Joe Marczynski