"There’s a great documentary Werner Herzog made last year," says Beck Hansen, "about the ancient caves in Europe that were discovered recently, and there’s a part where one of the scientists reconstructs a flute – a primitive woodwind instrument that was made out of an antler. When he finally reconstructs it he’s able to play ‘The Star Spangled Banner’. We’ve had the ability to play any melody in popular music for tens of thousands of years; who’s to say the melody for ‘Hey Jude’ hasn’t been around for 30, 40, or 50 thousand years? I know it’s far-fetched but there’s only a handful of notes and there have been human beings for millennia playing around with those notes."

After coming to the public’s attention with his breakout 1993 hit ‘Loser’, Beck has remained a fascinating figure within music. His second album received praise from Allen Ginsberg and Johnny Cash, while subsequent records (including the Grammy-winning Odelay) were critically lauded and routinely included in end of year lists.

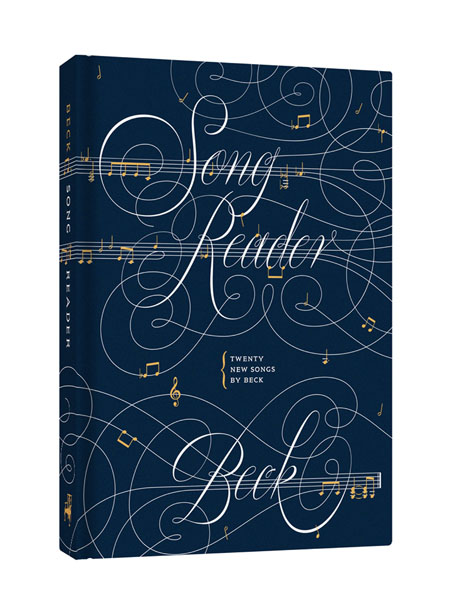

Now, nearly 20 years after ‘Loser’, Beck is set to release Song Reader, a book of sheet music for songs he’s written but not recorded, in collaboration with publisher McSweeney’s, who describe the book as "an experiment in what an album can be in the 21st century". Each piece of sheet music, housed in a "lavishly produced" hardcover carrying case, comes complete with individual illustrations from over a dozen artists. It’s being billed as his latest ‘album’, but the only way his fans will get the chance to listen to the songs is to either learn them themselves or trawl through the various versions on YouTube.

The Quietus spoke to Beck shortly after he arrived home in California from Australia – a country that he says gives you "a special kind of jet lag."

Have you spent much time listening to versions of these songs on YouTube, etc?

I’ve heard a few that are kicking around but I haven’t heard many because the book hasn’t been released yet. The only versions of songs out there at this point are ones that were released in advance. So it’s just a fragment or two.

Have you been pleased with the results so far?

Yeah, absolutely. There’s one I saw online, they put an impromptu little orchestra together. And it was great. I think they even changed the lyrics and I thought one of the lines was better than anything I’d written in the song.

When you wrote the songs, how did you you imagine that they would be performed?

There’s songs in the book where I’d written horn arrangements, but anything goes. I wanted to put together some sort of presentation that was simple and allowed other people to take the bare bones of what I was presenting and run with it themselves. I didn’t want to point them in any one direction; I wanted people to still feel like they could interpret the stuff in different ways. So some of the arrangements in the book are purposefully simple, or under-arranged – very basic arrangement of chords. Occasionally I did stuff that was much more stylistic, but for the most part I was trying to keep them simple.

And where did you imagine that they would be performed? Are these songs fit for an opera house, or YouTube videos of one person in their bedroom?

I would hope that somebody could play these songs for their own amusement and nobody would hear them, or a band could take them and record them and put them out on their record. Hopefully the songs just find homes. And find voices.

The idea for the Song Reader first came about in the 1990s, is that correct?

Yeah, it was quite a while ago. And I make that point because I didn’t necessarily think it was right for me to say that this was any type of reaction to the "state of music", or to how things have evolved with music being downloaded and file-sharing. This idea came innocently just from putting together a sheet music version of one of my albums and realising it was kind of deficient as a songbook. The songs that were in the sheet music book were songs that weren’t intended to be put down on a page. It got me really thinking about songs existing as sheet music and what kind of songs suit that format – the fact that the majority of our history came from notated music rather than recorded music.

If the original idea came to you in the ‘90s, why did it take so long for the idea to come to fruition?

During that period I was touring 10 months out of the year and then every few years I’d get a few months off and I’d spend that time in the studio making an album.

So it was due to lack of time rather than lack of enthusiasm for the project?

Yeah. And when I started to work on it in earnest I started to hit a few walls in my approach to it. I first started to work on it in 2004/2005, and I had cold feet with the presumptuousness of asking other people to play these songs. Then I started to feel like, "well these songs have got to be really, really good if you’re going to ask somebody to play them." So that would be a big block on the forward progress for a long time. Then that got me in to a whole exploration into what kind of songs in a culture get written down or passed through different eras – what kind of song exists outside of pop culture – songs that are perennial favourites.

Songs like ‘Oh Susanna’?

Yeah that would be a more extreme version. And a more modern version would be a classic rock song, or a Tom Petty song. These songs that have now become a modern folk music, the songs that people now sing around a camp fire. So that seemed to me a special category of songs, and not necessarily a category I’d ever thought about when writing songs. So I incorporated that into what I was doing and tried to strike a balance. I wanted songs that looked good on a page because I knew early on that the vast majority of people weren’t going to be playing these songs. I knew that they would be taken as a book – a book you pull off the shelf and read through. When you see the book it becomes obvious that it is an object; something you hold and read through and look at.

Why did you chose to have each song accompanied by an illustration?

In collecting old sheet much I realised how much the covers and the artwork were a part of the statement of the music. Originally it was just going to be in a book, but making them into their own separate pieces of sheet music allowed them to have their own identities and gave us a lot more to work with visually. And you have to imagine that when I was woking on the project and researching it there were piles of old sheet music all over the place. So the idea that it would be another pile of sheet music intentionally created a found pile of songs. Lost songs.

Would it be fair to say that the illustrations on the old pieces of sheet music were actually selling tools? Something to differentiate it from the other piece of sheet music being sold in a shop all those years ago?

Yeah, I mean they were very much record covers. There’s a whole universe of images from this old sheet music. We reused a few of the old images on these sheet music covers; there were a few that were old enough and we just took them and they were redesigned and changed around a little bit.

Faber’s description of the book says that it comes "Complete with full-colour, heyday-of-home-play-inspired art for each song." When, in your mind, was the "heyday of home play"?

It’s that moment when having an instrument in the parlor was accessible up until the point when the record player becomes dominant. I want to say some point between the turn of the century and the 1940s.

You say in the preface to the book that you "think there’s something human in sheet music, something that doesn’t depend on technology to facilitate it—it’s a way of opening music up to what someone else is able to bring to it." But prior to the printing press being invented and subsequently popularised in the 14- and 1500s, sheet music could only exist in its hand written form and so the sheet music you know today does depend on technology to facilitate it, does it not?

Yeah, but I think that the vast majority of music has been passed down. There are folk music songs that can be traced down beyond the printing press – that go far back. And I do wonder sometimes, some of these melodies that are kicking around the pop charts or in folk tradition, some of these melodies have been around for tens of thousands of years. Who knows? Because there wasn’t a written record of music before.

Other than your earliest albums, most of your records have had an average of 12 tracks on them, but the Song Reader contains 20 pieces of sheet music. Why 20?

Well I felt like, as a book, it needed to be more substantial: originally it was going to just be ten or twelve. But to be its own world it needed to be a bit longer. I feel that if it was shorter it would be more in danger of becoming just one thing. This allows for it to have some songs that are old-timey, some that more modern, songs that are more melodic, ballads, and others that are just more experimental, or odd.

Audience participation in your work is something you’ve touched upon before – The Information, came with stickers for the listener to personalise the artwork. Do you see what you’re doing with the Song Reader, and what you did with The Information as a way of giving people the tools to unlock potential they may not realise they have?

I think people are doing this sort of thing anyway – it’s just acknowledging it, or meeting them half way. People are already listening to a record that gets released and doing their own versions on YouTube, or taking the artwork and drawing it, or putting stickers on the CD case, or whatever. Some people are already engaging with it. The original idea for the book came more from the idea of song books. Whatever it implies in allowing people to engage and interact with the music is more of a by-product. I think it is an interesting idea and I am interested in how music changes when you perform it. The approach to my music has always changed or been influenced by playing in front of an audience. That is a form of collaboration.

Have you read David Byrne’s book How Music Works? He says something similar.

I haven’t read it yet. But yeah, look at any band who put out their first album and then watch their music change over a number of years and you’re watching evidence of the influence of an audience. Whether you’re a band playing in stadiums or if you have more of a cult following, it really is a huge factor in music.

Are there any plans for the songs to be part of future set lists?

Possibly. I wouldn’t rule them out. I do want people to have the chance to interpret them and hear them without any kind of reference, or without myself giving any type of direction. I know how I would play these songs so that’s the least interesting thing for me, but some of these songs have been sitting around for a number of years so I would enjoy playing them live.

Song Reader is released 6 December on Faber & Faber

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more