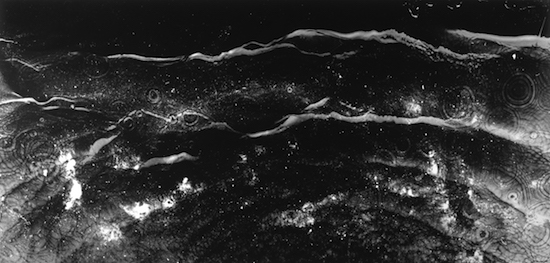

M. Flomen, Littoral Zone No.19.2009.Unique Photogram.48 x 96 in.Courtesy: the artist

While translating the Bolivian writer Jaime Saenz’s work into English, Forrest Gander learned of the influence of the South American Aymara language on Saenz’s writing. According to Rafael Nuñez, a cognitive scientist at the University of California, Aymara is the only studied culture for which the past is linguistically and conceptually in front of its speakers, while the future lies behind them. The word for future is also the word for behind, as is the word past the same as front. When people talk in Aymara about the future they gesture backwards; when they mention the past they gesture forward.

Gander’s work, often collaborative, spans decades and disavows genre: poetry, photography, film, translation, prose, dance. Dubbed an “artist of traces,” Gander’s most recent collection of poetry takes its title from C.D. Wright’s ShallCross, which she had just finished editing before her unexpected death in early 2016 (there is still one final book to come from Copper Canyon Press next year). ShallCross is dedicated to Gander, C.D.’s partner of more than thirty years: “for Forrest / line, lank and long, / be with.”

Gander’s elegiac collection offers a radically different mapping of time – more in line with the Aymara language than a conventional chronology of loss – gesturing both backwards to the future, and forwards towards the past he shared with Wright. In Be With, Gander hones his attention to the sixteenth-century Spanish mystic St. John of the Cross, the Mexico-United States border, and the challenges of caring for an ageing mother with Alzheimer’s. But Wright’s death permeates it all; a loss from which “nothing comes back” Gander commented earlier this year in an excellent Between the Covers podcast. Both Gander and Wright have long advocated for the proliferation of border-crossings – geographic, literary and otherwise. In Be With, the devastating effects of Wright’s death extend beyond each individual poem, spilling over the margins to bleed steadily into the next. ‘Beckoned’ begins:

At which point my grief-sounds ricocheted outside of language.

Something like a drifting swarm of bees.

At which point in the tetric silence that followed

I was swarmed by those bees and lost consciousness.

At which point there was no way out for me either.

The poem’s lineation conveys a drifting in and out of consciousness, reminiscent of the cover of the book, which is scored with thick, shifting black lines and their absences. Each time Gander comes to, he questions how to engage with and convey “a loss that every other loss fits inside.” “Creepy,” he says in ‘What It Sounds Like,’ “always to want to pin words on ‘the emotional experience.’” Language is unable to harness Gander’s “grief-sounds,” and so he must settle for the silent chasms of each line break.

Michael Flomen, Crunchtime 7.2009.Unique photogram.106x106cm. Courtesy: the artist

Miles Davis insisted that he didn’t listen to what was present in the music, but what was not there – the spaces “behind the notes.” Be With is punctured by its absences, by the long stretches of grieving that can be registered behind and between the words. Gander’s work has continually been involved with “waiting, listening, and silence,” as Wright wrote of poetry in The Poet, the Lion* – but Gander’s poetry has possibly never had to listen so closely to capture his internal and external surroundings. Similes won’t do anymore, as experienced in ‘Stepping Out of the Light’:

You find

yourself in another

world you weren’t

looking for where

what you see is that

you have always been

the wolves

at the door. Left

ajar, gaping, your own

door. And you burst

in as the Mangler,

you gouge out

your right eye which

hath offended. And you

burst in as the Great

Liar gorging

on your own flesh

and as Won’t

Let Go who shreds

your tendons, gnaws

your femur.

The poem ends:

now

you discern the

body of your body —

like a still,

hanging bell

that catches and concentrates

each ghostly, ambient

reverberation.

You takes on a growing number of guises: a pack of wolves, a demon-like figure, liar – the poem so struck in its concentration of grief, anger and regret that speculation or likeness is an impossibility for the disassembled self, echoed in the poem’s dismembered enjambments. It is like being clubbed round the head, then, when we reach the final lines – “body of your body – / like a still, / hanging bell” – and are awakened to one consequence of the self’s transformations; that once the speaker returns to the present “now,” they are able to “discern” that the physical self is only capable of being like something – arecollection, a “reverberation.”

In The Poet, the Lion Wright states, “My relationship to the word…is a matter of faith on my part, that the word endows material substance, by setting the thing named apart from all else. Horse, then, unhorses what is not horse.” From the beginning, Be With demonstrates the struggle for setting the named thing apart – but the inability for language to be able to express Gander’s experiences and feelings reverberates throughout. In ‘Son,’ Gander asks:

Why

say anything about death, how

the body comes to deploy the myriad worm

as if it were a manageable concept not

searing exquisite singularity?

It could be somewhat easy to commend Be With for an attempt to describe Gander’s particular experience of loss; however, this is not what I think the collection does, nor what I think the writing process that led to it ever sought to do. Instead, Be With traces the search for “a language beyond my own limited capacity to describe experience…maybe a language underneath description,” as Gander outlines in an interview with The Double Negative back in 2016. In doing so, Be With enters into conversation with collections of poetry such as Look by Solmaz Sharif and When My Brother Was an Aztec by Natalie Diaz. By perceiving, and pushing up against, the limits of language – “At which point my grief-sounds ricocheted outside of language,” – Be With is able to alter, to unhorse (as C.D. might have said) the role of language in grieving, in its (in)ability to translate one’s subjectivities.

Michael Flomen, Littoral Zone No.11.2009.Unique Photogram.48 x 96 in. Courtesy: the artist

In 1941 James Agee, a Southern writer of immense influence on both Gander and Wright, wrote: “If I could, I’d do no writing here. It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloths, lumps of earth, records of speech…A piece of the body might be more to the point.” With meticulous attention to imagery and melody, Gander assembles his own implements in ‘What It Sounds Like’:

As grains sort inside a schist

An ancient woodland indicator called dark dog’s mercury

River like liquid shale

And white-tipped black lizard-turds on the blue wall

For a loss that every other loss fits inside

Picking a mole until it bleeds

It was George Oppen who proclaimed, “the subjective is not outside of nature; it is included in nature, it is included in the world.” Each instrument brandished in ‘What It Sounds Like’ becomes a telescope, outwards-facing (as always with Gander), in order to tell us about what is going on internally within the speaker. The poem ends with a long, hard gaze: “You who were given a life, what did you make of it?”

The obsessions that have always haunted Gander’s work – ecology, the language of translation, the scientific – aren’t sequestered, but wielded anew to provide an intimate, particular portrait of living with loss within a world that, as Gander recognises, does not stop its “spins / nightly toward its brightness” as Wright wrote in Tremble. In is in this particularity that Be With is able to move beyond any sense of excess, grandeur or genericness. After all, Gander knows how restrictive aspiring to generalised trade routes of language can be. In In Translation: Translators on Their Work and What It Means he writes, “one form of totalitarianism is the stuffing of expression into a single, standardized language that marches the reader toward some presumptively shared goal.” In refusing to submit to a shared universality of feeling, Gander treats us, the reader, as equals. Gander may tell us, “It means just / what it feels like / it means,” but he never claims to know what “it” means for us.

In doing so, the presence of C.D. Wright strikes with the fluency of light throughout the collection. Gander’s invitation to be present in his seeing and being is evocative of Wright’s own generosity; “Come up on the porch with me,” she wrote in String Light, “I’ve got good peaches; I don’t mind if you smoke.” On Between the Covers, Gander states that he perceives the self as a constant collaboration, formed primarily in relation to others; “Who was ever only themselves?” Gander asks in ‘Son.’ Onto “the next stage,” Gander grapples with the mutuality he is uncoupled from after Wright’s death. However, collaboration is not confined to the living. In Poetry and Commitment, Adrienne Rich quotes Muriel Rukeyser, describing poetry as, “an exchange of energy…changing consciousness.” Be With is Gander’s collaboration with C.D. Wright, and therefore a boundless conversation about the possibilities of poetry.

The final section – ‘Littoral Zone’ – assembles a number of poems that Gander began work on prior to Wright’s death, developed in collaboration with the work of Canadian artist Michael Flomen. Over the past 15 years, Flomen has spent various nights placing sheets of photosensitive paper in creeks in Canadian forests. The results, as exhibited alongside Gander’s poems, are photographs that have been marked by the environment/s in which they were placed – streaked with patterned rains, starlight, the shadows of fish swimming in the creek underneath, the fireflies darting above. Similarly, Gander’s prosaic, compressed language in the section rests attuned to his surrounding environment; “For though we have no criterion for how to see and are not sure what we are seeing, we are plunged into sensation,” he writes, by “the forces / of that which cannot yet / be sussed.”

Michael Flomen, Exit,2007.Unique Photogram.50x 40 in. Courtesy: the artist

As Flomen’s photographs unintentionally document the changing world and its affecting elements, such as the marks left by bryozoa and freshwater jellyfish as they increasingly move inland to waters getting warmer, Be With shows us that once we increase our attentiveness, we are able to see that “things are in fact moving, that there are relationships,” as Gander stated in The Double Negative. But Gander is not buoyant enough to believe that this movement takes a solely positive progression; “days to come will crack open without you, / dropping their yolk over places you’ve walked.” Five poems each titled ‘Exit’ countdown to the sixth, and final poem of the book, ‘Entrance’:

From

afar, do you see me now

briefly here in this phantasmic

standoff riding

pain’s whirlforms?

Like Schrödinger’s Cat, a poem is altered simply by our looking (as are we). Whatever may be proclaimed about solitude and writing, nothing occurs in isolation – not writing, not reading, not feeling. It is an everlasting exchange, a dialogue with books older than grandparents, memories that feel come clearer to us than what we had for breakfast – dreams, lists, who is in the room, who isn’t in the room. “Those dark Arkansas roads,” C.D. Wright recalls Miles Davis, “that is the sound I am after.” Be With stutters, flinches and refuses to turn away from the inabilities of language, the abyss of absence and loss, the possibility to register motion among the silences.

However crucial it can be, Gander does not kid himself that poetry can restore the dead, or adequately anaesthetise those left living. “Poetry is not a healing lotion, an emotional massage, a linguistic aromatherapy,” Adrienne Rich wrote in 2006, “Poetries are no more pure and simple than human histories are pure and simple.” Rather than reaching for epiphany, reconciliation or an answer, Be With exposes us to a life that is battling to move through the world while clutching a kaleidoscope of feelings, perspectives and questions. In continuing his collaboration, his conversation with C.D. Wright, Gander has created a book that acts as part of the process of loss, grief and movement – “the standoff riding / pain’s whirlforms” – rather than just mirroring it. As St. John of the Cross himself noted, “I entered in unknowing and there I remained unknowing.” Perhaps this is the only state of being that can ever get close enough to glance a realm “more real than life.”

- Full title, The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Garolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All

Be With by Forrest Gander is published by New Directions