A new campaign by comics people is drawing attention to the role of Amazon in sponsoring comics festivals through their digital ComiXology platform. At the time of writing both the festivals mentioned and the artists named skew more towards America and Canada, but Thought Bubble gets called out, and Simon Moreton is one of the few UK signatories I could spot. Inspired by Amazon’s labour practices, their impact on communities they occupy and the provision of technology used by America’s Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE), it’s fierce stuff:

"Art is not apolitical, and art workers are not afforded special neutrality as innocent bystanders. We must examine the ways in which Amazon uses sponsorships to whitewash its brutal exploitation of workers and the disastrous effects it has on the cities it moves into. We must examine our culpability in a system that enforces and profits from the violent, inhumane treatment of immigrants; a system of sting raid operations and concentration camps that separates families and murders both children and adults via neglect. When we take money from Amazon and look the other way, we are allowing these actions to happen with our silence.”

As ever, here at tQ we strongly encourage you to buy your stuff from specialist independent retailers and direct from publishers and record labels.

Meanwhile, the first outing of the Hackney Comic and Zine Fair, a new event certainly not sponsored by Amazon, was by all accounts a roaring success. Organised by Joe Stone, it featured many of the artists and publishers reviewed in this column over the years, including John Riordan, who is running an (already fully funded) Kickstarter for a hardcover collected edition of the excellent Hitsville UK he produced with Dan Cox. The blend of weird music and satire is likely to sit well with readers of this site – do take a look if you’ve not seen it or if you want to upgrade your individual issues to a copy that might survive the coming apocalypse.

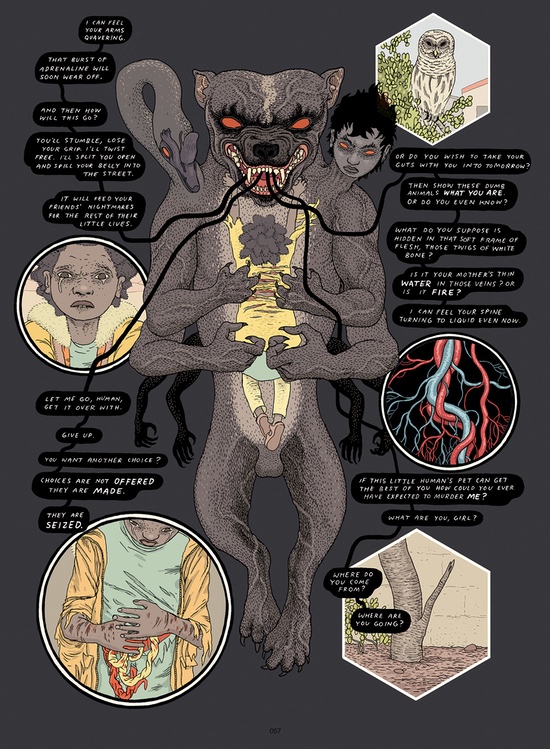

Anders Nilsen – Tongues #2

(Self-published)

Anders Nilsen’s Tongues #1 was a striking comic in both content and format, a retelling of the Prometheus myth that introduced us to a range of deities, humans and animals that could well turn out to be his best work yet. The second part continues the work of setting up the story, introducing new characters and settings as well as updating us with those we’ve already met.

It is a beautiful comic that draws us in from the first panel, barely giving us time to note the appearance of more French flaps and inserts that make this series such a tactile delight. We meet a young woman whose parents want her to choose between three undesirable prospective husbands but who is much more interested in the being who is her lover, and also a swan, a demon dog and seemingly the evil that Astrid, the little girl from #1 is supposed to defeat. Speaking of Astrid, it’s not entirely clear where she is but it’s no longer the desert, and she is part of a family group for now. We also spend some more time with the military types who picked up the man with the toy bear strapped to his back (nicknamed Teddy Roosevelt by his captors) who turn out to be precisely as lovely as one imagines mercenaries to be. The eagle and the monkey are back, but not the chicken. However, there is a mysterious owl that undoubtedly has a role to play in forthcoming parts. As I said, Nilsen is still firmly in the setup phase.

Towards the end there’s a double page spread layered with meaning and possibility. A tiled minaret is in the foreground, desert in the rear, and in the middle shadowy, hostile forces of oppression wreak havoc on the locals. Overlaid on this is a discussion between the eagle and the god with whom he plays a daily game of chess that ends with the bird feasting on the deity’s liver. The divine being observes that “the world’s chaos can look remarkably like pattern to even the most careful observer” as we see patterns on the tower and chaos on the streets. It’s an example of Nilsen’s brilliance, a page to return to when we know more. I can’t wait for the third part. Pete Redrup

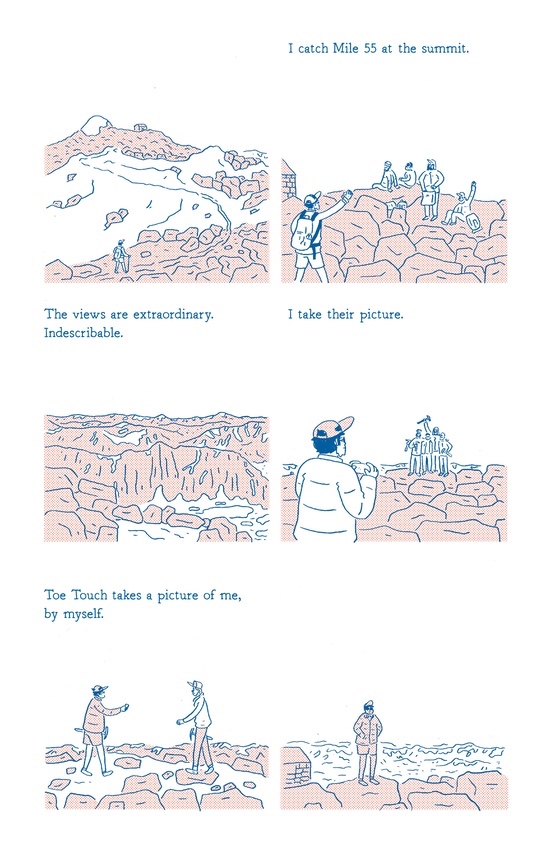

Luke Healy – Americana

(Nobrow)

Last seen with the splendidly meta Permanent Press from Avery Hill, Luke Healy is back at Nobrow for his latest comic, Americana. Whereas his previous book with them, How To Survive In The North, gave an account of Ada Blackjack and Robert Bartlett’s risky travels in the Arctic in the early twentieth century, this time the adventure in question is all his. In 2016 he spent several months hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, a 2660 mile route from the Californian / Mexican border to where Washington State meets Canada, a challenge for anyone, let alone a first-time hiker.

Healy begins with a prose introduction to his lifelong fascination with America, and his numerous attempts to gain residency there. An alumnus of the Centre for Cartoon Studies in Vermont, once he’d completed his studies he had been forced to return home to Ireland. After a few pages he transitions to the borderless panels that will be familiar to readers of his other work, and the book often switches back to prose for a few paragraphs or pages, a technique that works really well in drawing us in as a voiceover can in a film. Healy’s unadorned visual style particularly suits the locations he hikes through, from desert to woodland.

The trail has its own lingo, which we swiftly learn: trail name, zero, hikertrash, thruhiking, trail angel. We also meet a cast of recurring characters as he falls behind then gets ahead gain, encountering the same people in numerous locations. As he works through his unrequited love for the USA, he struggles with the constant urge to quit. This is clearly the sort of situation that forces you to come to terms with your personality, your faults, strengths and weaknesses, and he is frank about this. By describing a relatively short part of his life, Healy leaves us feeling like we know him intimately. It’s a real gift to be able to do this, and is a testament to his excellence as a cartoonist. This is another superb work from Healy that draws you in from the start and compels you to finish much more quickly than than the endeavour it describes. Pete Redrup

Simon Hanselmann – Bad Gateway

(Fantagraphics)

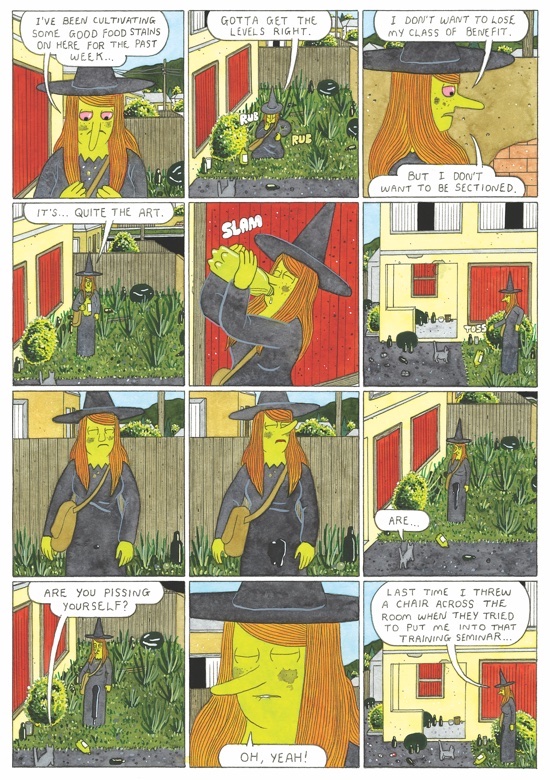

A couple of years have passed and Simon Hanselmann graces us with another Megg and Mogg book. Bad Gateway is a delightful object to hold, with a foiled front cover and suitably evil black edge painting on the pages. As someone getting no younger I appreciate the increase in size to A4; although it won’t sit so well alongside its predecessors, it makes it much easier to read than some of the minis (Ten Year Anniversary Special, I’m looking at you) which really ought to come with a magnifying glass.

Bad Gateway begins with a reprise of recent events including Owl moving out and Werewolf Jones moving in. Now Owl is no longer paying 80% of the rent, financial issues have become a major problem for Megg and Mogg. Werewolf Jones might be a more fun housemate but he certainly isn’t as altruistic as Owl could be when circumstances demanded, so there will be no help with the bills. Although Hanselmann tends to avoid any detail that could anchor his stories to any particular political administration, there’s a squeeze on welfare eligibility that is very 2019, and so Megg has to work hard to ensure her payments continue. They’ve never seemed particularly content with their lives, but it’s noticeable how much unhappier nearly everyone is are this time. In particular Mogg is desperately lonely as Megg tries to work out what and who she wants, and an extended flashback to her teenage years illuminates many aspects of the latter’s personality.

As is customary, the moves from heartbreaking to hilarious, appalling to even more appalling, are frequent. Once again Hanselmann displays his unique gift for being extremely compassionate towards his characters despite portraying them as living disastrous lives, and this book is much bleaker than the others, if that’s possible. Again, very 2019. As always, I am left wanting so much more – this is an essential purchase. Pete Redrup

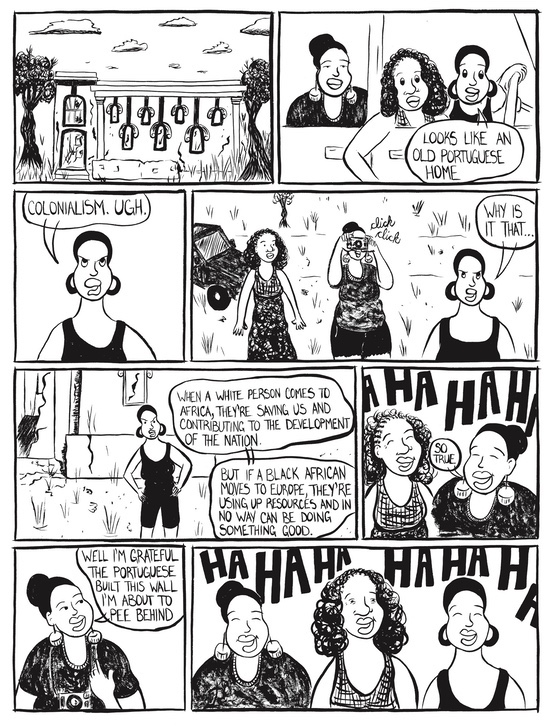

Ebony Flowers – Hot Comb

(Drawn & Quarterly)

The way childhood is depicted in the first story Hot Comb reminded me of Lynda Barry. This is not in a derivative way, but rather in the affectionate but unflinching depiction of childhood poverty and the complexity of family relationships. Since the book shares its title with this story, we can assume its high status in this collection. Hot Comb recounts a girl named Ebony’s first time getting her hair relaxed, aged 11. Having moved from a trailer park to an all-black neighbourhood near Baltimore, her natural hair gets her bullied and so her mother, grudgingly, assents. What follows shows us a little of life in the trailer park, her mother’s fears that her children were becoming too white as they copied their friends, and more about how things changed in the new neighbourhood. A story about hair on the surface becomes a nuanced reflection on race, class and identity. This is what the best writing does – resonates with those whose experiences are similar, and produces empathy in others.

The other, shorter, stories cover wide ground. Big Ma is about addiction and the impact this has on the wider family, while The Lady On The Train describes an encounter laden with casual racism. My Lil Sister Lena has a black girl’s hair as object of curiosity for the white girls on her softball team and Last Angolan Saturdayshows the pleasures of a trip to the beach where the journey with friends is as important as the destination.

Ebony Flowers is an important new voice, and it’s great to see her work coming from a large publisher. There’s so much to enjoy and unpick here, great storytelling with multiple layers celebrating family, friendship, race and community. In a time when many are keen to bring division between different groups it’s so important for voices to be heard, for people to see their lives reflected in books, and for others to hear those voices. This is clearly a view widely shared, as Ebony Flowers has just won the Ignatz for Best New Talent. Pete Redrup

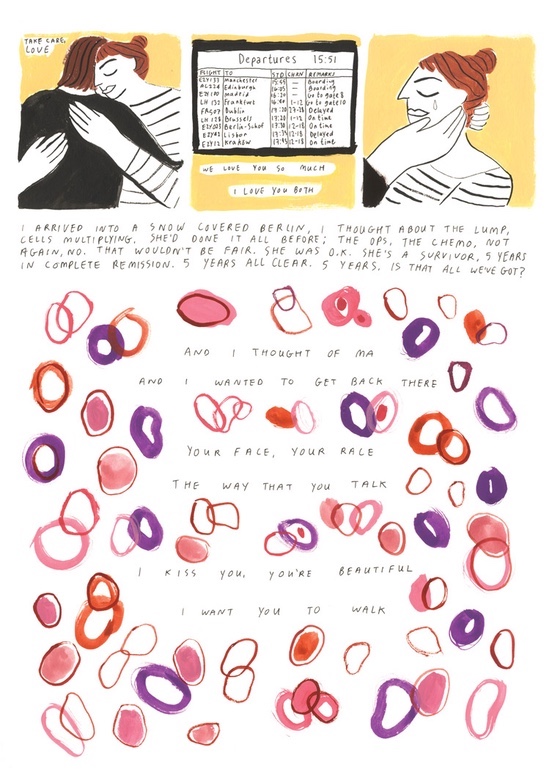

Jayde Perkin – I’m Not Ready

(Self-published)

Bristol-based illustrator Jayde Perkin won last year’s ELCAF X WeTransfer prize, and some resulting Arts Council and Lottery funding allowed her to produce I’m Not Ready. It’s a reworking of some of her minicomics including the excellent Time May Change Me, an exploration of personal grief and David Bowie following the loss of her mother.

The book begins with Perkin returning to her life in Berlin the day before Bowie’s death was announced, as her mother undergoes tests. Several panels illustrate childhood memories of Perkin and her mother listening to Bowie together, interspersed with health updates. The transition from the news about the return of her mother’s cancer to the news of her death is sudden in the terrible way that these things can be – you just start to take stock of what is going to happen, and then it has.

From this point onwards, the book is a deeply personal, open and honest account of how Perkin is coping with her loss and grief. It’s a great illustration of the way the medium of comics can be so expressive, the juxtaposition of words and image bringing more in combination than either could alone. The flattened pictures, eyes always shut, give a childlike simplicity and a focus on the interior life reminding us that no matter what else is going on, we are ultimately alone with our thoughts and feelings, and we need to find our strength within. I’m Not Ready is a beautiful comic that everyone can relate to, an exceptional work deserving of all the praise it has garnered. You can buy a copy from Perkins’ webshop. Pete Redrup

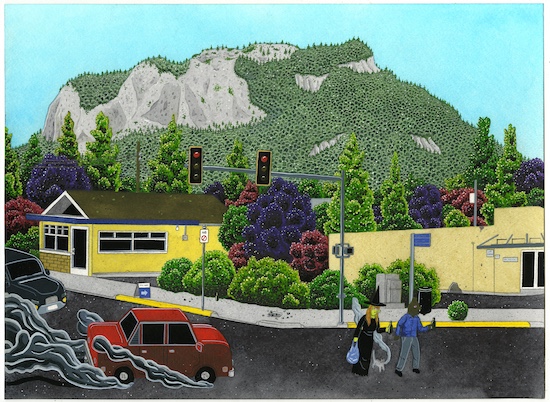

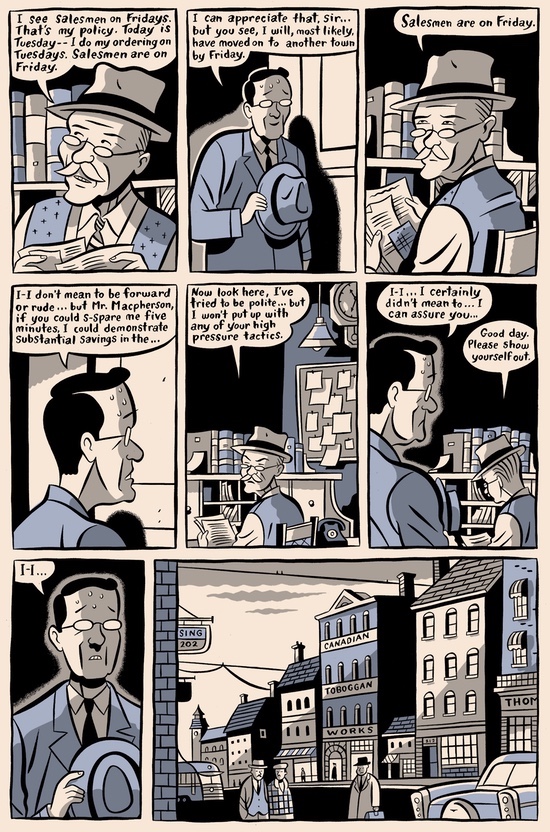

Seth – Clyde Fans

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Once again, it’s a huge Drawn & Quarterly book that has been over 20 years in the making – they seem to have produced a few of these recently. Clyde Fans is an eyecatchingly opulent hardback in a slipcase, as solid as the buildings depicted within. This is a quiet story about pretty ordinary lives in which not much happens. Were Seth not such a gifted artist this might be a problem, but in his hands the gentle amble through this selective history of the titular fan manufacturer and the lives of the Matchcard brothers is a pleasure from start to finish.

The story is divided into five parts with a non-linear chronology. Beginning in 1997 we meet Abe as he walks through the old offices of the long defunct company, and the family home on the floors above. Almost a hundred pages are devoted to this meander, as he fills in some of the back story and muses on the art of selling. The next section introduces his brother Simon as he embarks on a disastrous attempt to become a salesman 40 years earlier. As a painfully introverted character, it’s hard to imagine anyone less suited to this life, and when we move forward to 1966 he has pretty much become a recluse while he cares for his elderly mother. The brothers seem very different and their interactions are fraught with tension and a lack of understanding of each other. It’s nearly 350 pages before they have an honest conversation which reveals something of their true selves.

In interviews Seth has described the brothers as being the two sides of his personality, and this makes sense as both of them need a little of what the other has. Neither is particularly sympathetic when we first meet them, but that changes once we see beyond the faces they present to the world. One brother is looking for his father, the other for himself. Seth is telling us not to be paralysed by inaction, wallowing in thoughts of the past, nor to lead the life that isn’t the one you want, or you will end up bitter and unhappy.

Don’t pick this up expecting much to happen quickly or you will be disappointed. It’s an introspective work with much of the heavy lifting being done by the outstanding illustration, a cautionary tale that tells us to be like neither character. There’s also a sense that this has taken a little too long to come to conclusion. I feel, appropriately, nostalgic for the story I first started to read more than a decade ago, but the comics landscape has changed. Compared to the rest of D&Q’s current output this feels a little dated, the introspection telling us about Seth but not revealing many wider truths about the world we live in, although it is unquestioningly a beautiful book. Pete Redrup

James Stokoe – Sobek

(ShortBox)

Sobek (also known as Sebek, Sebek-Ra, Sobeq, Suchos, Sobki, and Soknopais) is an Ancient Egyptian crocodile god of the waters and specifically the Nile. Sobek the comic is an absolute joy from beginning to end. Canadian comic book artist known for Orc Stain and Godzilla, James Stokoe’s stunning line-work and subtle atmospheric colouring (suffused with tones of the jungle at sunset) make this book a pleasure to look at in the first instance. If the story was no good I would recommend picking it up just to look at the art. I mean really, you can feel the texture of every scaly inch of the many crocodiles and crocodile gods herein but their expressions are still clear and expressive. This might be gushiest review I’ve ever written here – sorry.

Those expressions lend themselves well to the deadpan comic timing of the dialogue. Sobek is both a celebration of the opulence of myth and history and a wickedly wry mockery of it. The denizens of the holy city of Shedet travel along a magical river way to visit the great god Sobek and entreat him for help – their city has been overrun with enemies from the rival cult of Set (or Seth, Setesh, Sutekh, Setan, Seth Merksamer, Seteh, Setekh, or Suty, god of chaos, fire, deserts, trickery, storms, envy, disorder, violence, and foreigners). The great crocodile god consents to help, but at what cost?

What follows combines epic filmic violence and comedic insight into the nature of mankind’s relationship with the divine. Probably. Short Box, the quarterly, independent comics box publisher headed by Zainab Akhtar, who also edited this book, has increasingly been offering their more successful titles for sale individually online. As such Sobek is currently available here; the box itself is also well worth an order if you want a low effort selection of diverse comics talent headed your way. Jenny Robins

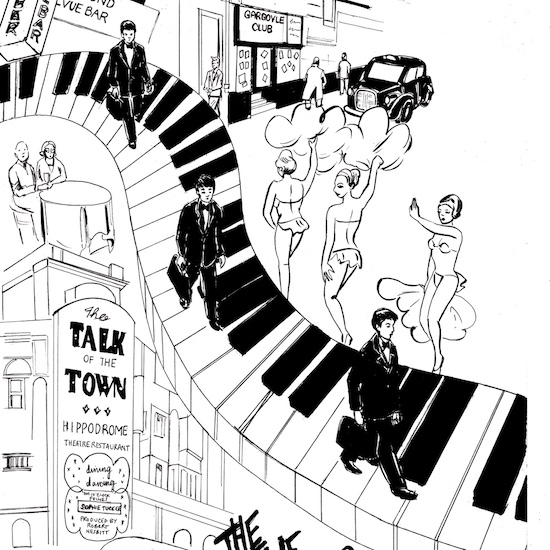

Jessica Martin – Life Drawing – A Life Under the Lights

(Unbound)

Life Drawing dances lightly between reminiscences in this graphic memoir of Jessica Martin’s life as a West End regular, Spitting Image impressionist and Doctor Who actor. As an artist, I was most fascinated by the parts that showed the author’s relationship with drawing alongside her relationship with the stage and screen – such as a very effective series early in the book where she shows herself obsessing over a series of glamourous actresses as she grows up, and the types of drawings she did of them at the time. Martin’s drawing style now is far from childish, showing a highly sympathetic realism with a light touch and excellent economical use of backgrounds and contrast. Aficionados of the theatre would probably catch more of the names dropping like chandelier crystals throughout the book than I did, but you don’t need to know who all the famous names and faces are to enjoy reading Jessica’s pithy anecdotes and wry musings aside on her life under the lights. As with any telling of a whole life to date (not that Jessica’s is anywhere near done, I hope) the story does move apace and feels more like a highlights reel than a feature film at times, but it never loses its momentum so the details are well chosen. There’s also some lovely insights and moments of reflection on the push and pull of the creative life, whether on the stage or the page. To keep making the good work we dance the dance of compromise and uncertainty, triumph and disaster. But we never stop hearing the call to create, so the good work comes when we keep dancing. Jenny Robins

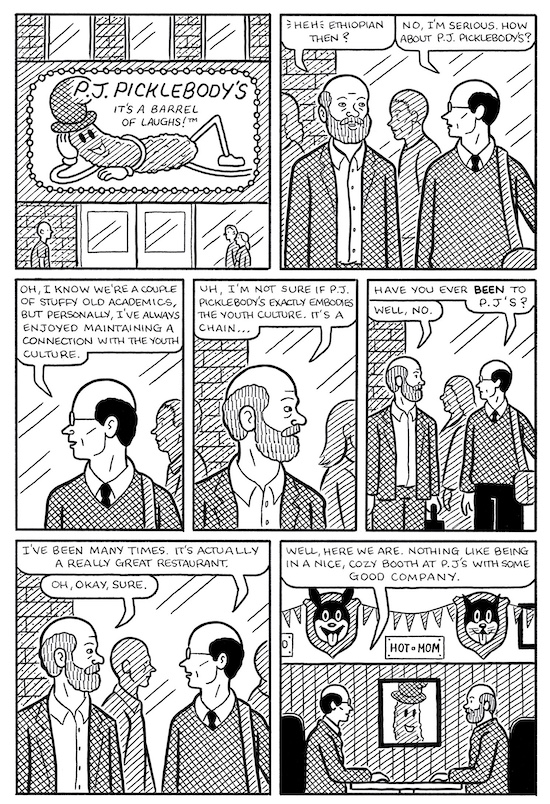

Nick Maandag – The Follies of Richard Wandsworth

(Drawn & Quarterly)

The first major release from Nick Maandag, The Follies of Richard Wandsworth is a darkly comic collection of stories concerning a neurotic academic, an unhinged fire marshal and a young monk struggling with abstinence.

The first arc concerns Richard Wandsworth, a professor struggling to manage an obsession with a young female student and intellectual oblivion at the hands of a professional rival.

In Richard Wandsworth, Maandag crafts an obnoxious – and at times perverted – figure who’s easy to pity, and even detest. Despite this, it’s hard not to secretly root for him, despite his social ineptitude and proclivity to alienate peers, colleagues and students alike.

Whether it’s being caught attempting to climb a wall after eavesdropping on a private conversation, or stripping off after smoking too much weed at a college party, Richard falls into Curb Your Enthusiasm-esque embarrassing situations with alarming regularity. The strength of this first section is its subtlety – conversations between professors at work functions provide much of the witty dialogue, while the inner turmoil of Richard’s thoughts provides a candid look into a deeply troubled mind.

Night School, the second – and weakest – of the three stories sees a fire instructor hosting a chaotic visit to a late night business class. While dealing out bizarre punishments to unruly students, namely the consumption of a charred dead squirrel, this bizarre story contains flashes of early Daniel Clowes-style absurdism and a barely comprehensible ‘plot’. This second act, while entertaining, doesn’t provide the same narrative payoff as the other two.

The final section, The Disciple concerns the sexual frustration of a young monk at a co-ed Buddhist monastery. The protagonist, Adrian, struggles to focus on achieving inner peace ahead of his raging libido, lusting after fellow monk Anastasia. Surrealism is never far away, even in this minimalist tale, with Brother Bananas among the cast, a fellow Buddha devotee who happens to be a small monkey. We soon discover that abstinence doesn’t apply to everybody at the monastery – especially those at the top. Following an ultimatum with his master, Adrian is taken on a series of amusing sex education lessons, with Brother Bananas in tow.

It’s tough to be actually funny – most books with pull quotes claiming “it had me crying with laughter” don’t usually raise more than a wry smile in practice. Follies bucks this trend, with genuine moments of deadpan comedy. Maandag creates a sense of unease in all three stories that’s difficult to define, flitting between unsettling weirdness and well-crafted visual jokes. If either, or both of these themes appeal, Follies is well worth a look.Joe Marczynski