We have a big change on the comics column team this month: editor Aug Stone has moved on. He’s going to be spending some more time working on his own comics and fiction, so do check out his stuff. He’s also concentrating on music production, and has just co-produced the new solo single by Ani Saunders of The Pipettes (as Ani Glass), which came out July 20th. He’ll still be writing the odd piece for us here. Anyway: some excellent titles up this month. On to the comics.

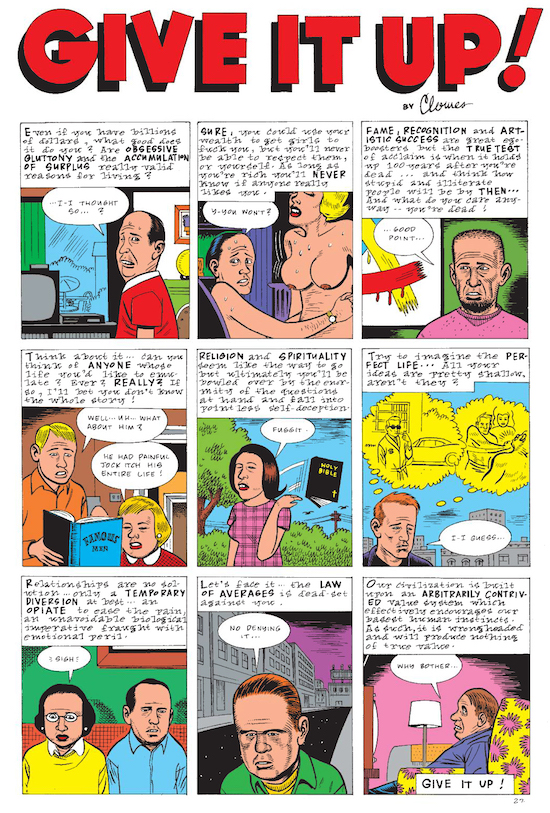

Daniel Clowes, The Complete Eightball 1-18 (Fantagraphics)

As reissues go, this is an expensive but absolutely stunning piece of work. Collecting the first 18 issues of Eightball in a two-volume box, it demonstrates mind-boggling attention to detail. Fantagraphics replicate the way the comics were initially presented, so the paper stock and colour reproduction varies from issue to issue. For example, the Ghost World part of Eightball #16 was erroneously printed in orange rather than the intended blue, so that’s what the box includes. There are some great recent Clowes interviews where he talks about the efforts made to put this together. He’d sold nearly all the original artwork for these, which needed to be tracked down and rescanned as many of the early prints were from poor quality scans. When you know how much work it took to put this set together, and actually feast your eyes on a copy, the eye-watering price tag makes more sense.

The format of these comics tended to be a few short pieces plus a section of a longer work, and then a (frequently very entertaining) letters page and some ads for Clowes-related ephemera. An awful lot of this material is available elsewhere. For example, Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, Pussey! and Ghost World are all here. Various other strips have appeared in Lout Rampage!, Orgy Bound, Caricature (all three of which have long been out of print) and 20th Century Eightball. Many Clowes fans that already own these may therefore feel this is something they can live without, considering that the cheapest copies for sale online are more than £50. However, reading the comics as originally published is a different experience from reading the graphic novels compiled from the contents. Eightball #1 is subtitled ‘An Orgy of Spite, Vengeance, Hopelessness, Despair, and Sexual Perversion’ and it’s this that is more strongly emphasised when the individual comics are read (although, it must be said, Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron has those qualities and more all by itself).

Each volume ends with Beyond the Eightball, fascinating and hilarious notes by Clowes on every issue. His essay, ‘Modern Cartoonist’, is also included as a separate pamphlet as it was with Eightball #18. There’s no doubt that this is one of the finest comic releases of the year. Clowes has a unique voice, and this is simply brilliant work, wickedly funny and flawlessly presented. Save up for this; it’s unmissable. — Pete Redrup

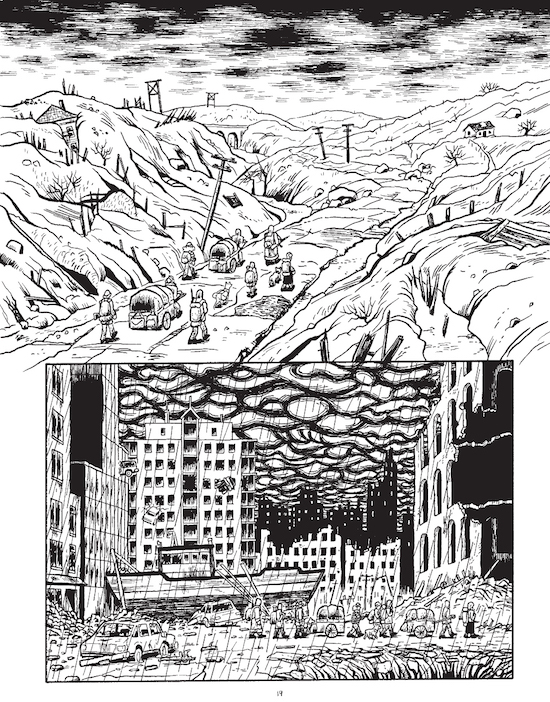

Josh Simmons, Black River (Fantagraphics)

Josh Simmons’ Black River is a genuinely horrific vision of a post-apocalyptic world. It opens with a group of women, one man and a dog finding a storeroom with some much-needed supplies: "Yes indeed, this is a happy day," their leader Seka remarks. But happiness is a rare element in this book, and this discovery – guns, booze, water and clean socks – is about all we get.

A first glance at the character art style gives a slightly misleading impression, perhaps implying that we are in for a softer ride, but this is swiftly dispelled – first by extensive expletives and then by shocking brutality. The backgrounds, however, depict a hellish world right from the moment we leave the storeroom. Widespread devastation, harsh landscapes and terrifying skies are on every page. There’s no explanation of how the world came to be this way, and no comment from the group as they walk past burning cities, ruined wastelands and scenes of utter chaos, with details such as wrecked cars embedded in the upper windows of tower blocks. This is just normal.

There are occasional pockets of society, such as Smitty’s, the motel and comedy club visited early on. Simmons gives a knowing wink to the genre convention of an apocalypse with no specified cause when an ill-fated comedian jokes about the greatest hits of asteroid, nuclear, earthquake, volcano, virus and singularity all going down within a few years of each other, although this is a joke in diegesis as well as for the reader.

Looking like a cross between the settings of the Fallout games and The Road, this is a world without mercy, as the demise of the first character establishes. Almost every scene ends in death or a bloodbath, and no opportunity for gore is passed up. When a character comments "I’m so excited…I can’t wait to see how much worse things can get…", the answer is a lot. It doesn’t take much imagination to anticipate what sort of threats a mostly female group typically face in this genre of fiction, but these characters can more than hold their own in a struggle.

As horrific as the events are, the women are more tormented by their psychological demons, and it’s ultimately this that presents the biggest threat. If you’re looking for happy endings, this isn’t the comic for you. There’s only one type of closure in this world, and the most anyone can hope for is that when death comes it is swift. Josh Simmons does not pretend otherwise, and Black River is all the more powerful for it. This is a bleak, chilling but excellent graphic novel. — Pete Redrup

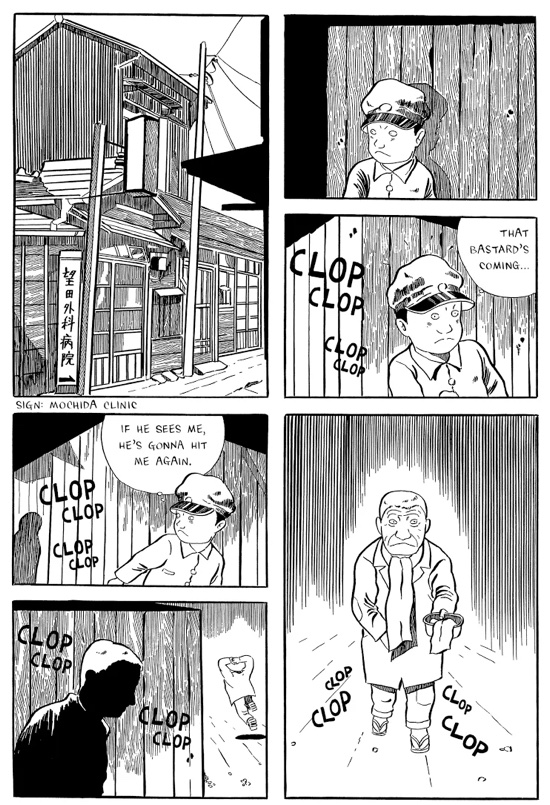

Tadao Tsuge, Trash Market (Drawn & Quarterly)

Trash Market is a collection of gekiga by Tadao Tsuge originally written in the late 60s and early 70s, portraying life in post-WW2 Japan. Anyone who has watched Grave of the Fireflies will know that this is a period in which life was unrelentingly hard for many, and Tsuge does not shy away from revealing this. These stark, unsentimental, text-heavy comics depict a dog-eat-dog world without resolution or happy endings.

Like the work of gekiga pioneer Yoshihiro Tatsumi, the drawing style is as far away from the manga that younger readers flocked to – as is the subject matter. The main body of the book consists of six stories: Up on the Hilltop, Vincent Van Gogh is first. Ostensibly concerned with the titular artist, exposition about his life and work is drawn against a backdrop of rising rents and food prices and brutal state suppression of protests that resonates today. Song of Showa is a bleak tale of domestic abuse in which a boy suffers at the hands of his father and grandfather, perpetuating the cycle of their own lives. Manhunt tells of a man who walks away from his wife and job, full of ennui and without resolution. Gently Goes the Night is about an apparently respectable family man, looked up to by relatives and colleagues, who is haunted by flashbacks to the war and takes out his frustrations on a young woman who makes the mistake of showing him kindness. A Tale of Absolute and Utter Nonsense tells of violent revolutionaries, and features a cartoonist who departs the story just before his comrades suffer their inevitable fate, perhaps showing the detachment of the author from the lives of those around him. Finally, Trash Market is set in one of Japan’s controversial, commercial ooze-for-booze blood banks (where Tsuge worked for many years and believes he picked up hepatitis C) and features a varied cast of precisely the sort of people who are sufficiently desperate to sell their blood (and more) to survive.

As well as the stories, Drawn & Quarterly gives us an edited selection from a series of autobiographical articles called The Tadao Tsuge Review, as interesting as the gekiga themselves, highlighting the autobiographical elements within. Translator Ryan Holmberg wrote an equally fascinating piece, Portrait of the Artist as a Working Man, which follows. Together, the two paint a fascinating picture, and recount the familiar artistic challenge – one who seeks to work without commercial compromise may find it hard to earn a living doing so – which Tsuge resolved by having a series of blue collar jobs and working on comics in his spare time. As he observes, "too dark, won’t sell, no commissions: one can’t support a family on that pattern."

The stark, simplistic drawing style and total absence of hope mean that this is not an easy read, but is ultimately a fascinating and rewarding one. — Pete Redrup

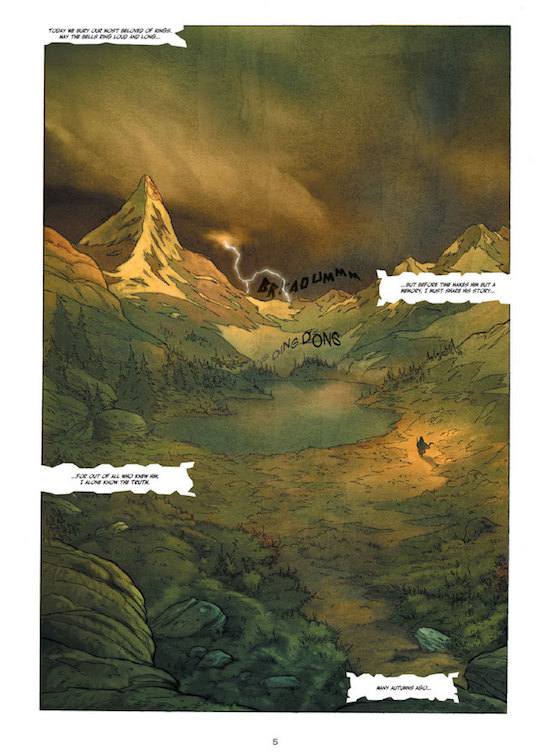

Manuel Bichebois (writer), Didier Poli and Guilio Zeloni (artists), Child Of The Storm (Humanoids)

Humanoids continue to put out beautiful-looking books, and their latest, Child Of The Storm, is another one to behold. As stories go, it’s the standard outcast with special powers – in this case somehow connected to the electrical charge of thunderstorms – searching for his roots and the origins of what makes him different. During the course of which, war rages throughout the land and we’re shown the madness such aggression engenders. There’s love, betrayal, alchemy; a deranged wizard has grand plans to resurrect his dead son. It’s good fantasy, with a steampunk edge, geared towards both young adults and more mature readers but not suffering for having set dual sights.

Claude Ecken writes in his Afterword how Bichebois is actually subverting typical fantasy fare though this perhaps isn’t readily apparent. Like I said, it’s a good story, but it’s the artwork that’s truly impressive, that keeps one flipping the pages. Both Poli and Zeloni (taking the reins for the second half of the book) do an excellent job with just about everything – the inventiveness and detail of the environments, the range of expression (and there’s a lot of it) of the characters. It’s an enticing world to wander through. – Aug Stone

Sean Michael Wilson (writer) & Akiko Shimojima (artist), Cold Mountain (Shambhala)

Shambhala Publications, known for their books on ‘enlightened living’ (psychology, philosophy, Eastern religion…), have begun publishing comics by martial arts enthusiast Sean Michael Wilson. Cold Mountain, subtitled The Legend Of Han Shan And Shih Te, The Original Dharma Bums, offers a glimpse into the lives of these two playful Chinese mystics who lived during the Tang dynasty (618-906 C.E.)

Han Shan is old but still youthful, having lived through army life and a career and family before making his way to the mountain. Shih Te (‘the foundling’) is his ‘street-kid’ sidekick. We see the two mostly laughing and reciting poetry whilst occasionally getting up to hijinks at the local monastery as well as mocking would-be students who have come to learn from them (a Zen form of encouragement along the spiritual path). The book also reproduces quite a few of their really-very-good Zen poems, written on rocks and tree trunks as was their method of leaving these compositions to posterity. – Aug Stone

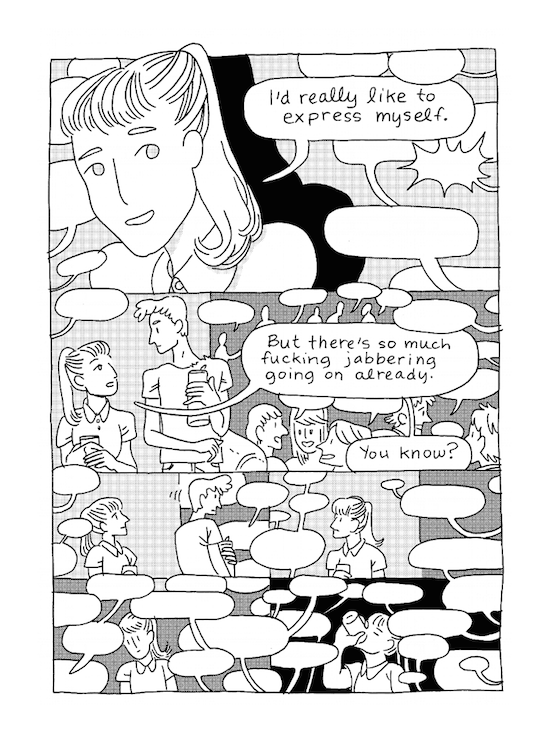

Laura Knetzger, Sea Urchin (Retrofit Comics)

Cute comics provide little of interest. They demand acceptance (and celebration) for nothing other than the act of being cute. Sea Urchin fights this temptation, though, by pairing the aesthetic with ideas like introversion, depression and the Internet as a way for the artist (Laura Knetzger) to question her style, as well as making a focal point of her own awareness of it.

It’s essentially a critical analysis of one’s self, asking the heavier question of whether or not an individual truly is, or whether they’re/you’re just a copy of those billions already available (and now easily noticed because of social media). At times it can be incredibly relatable; it seems to say what you’ve meant to. It even gives the impression that it may break through the millennial obsession of identity and uniqueness, and offer the blunt realisation that, no, it is not the chosen generation.

But it doesn’t. It clarifies the idea of each of us representing a miracle, and leaves it at that. Maybe that makes sense. Maybe we are what we are, and we just happen to share several commonalities, while still being individually beautiful. That’s probably all true. I just wanted something meaner in the end to suit where it began. The anger, frustration and doubt of this comic book read entirely true to me, while the glad ending just feels false. Maybe that only says something about myself, but I’d like to think the artist was on some similar page before acting like she wasn’t. – Alec Berry

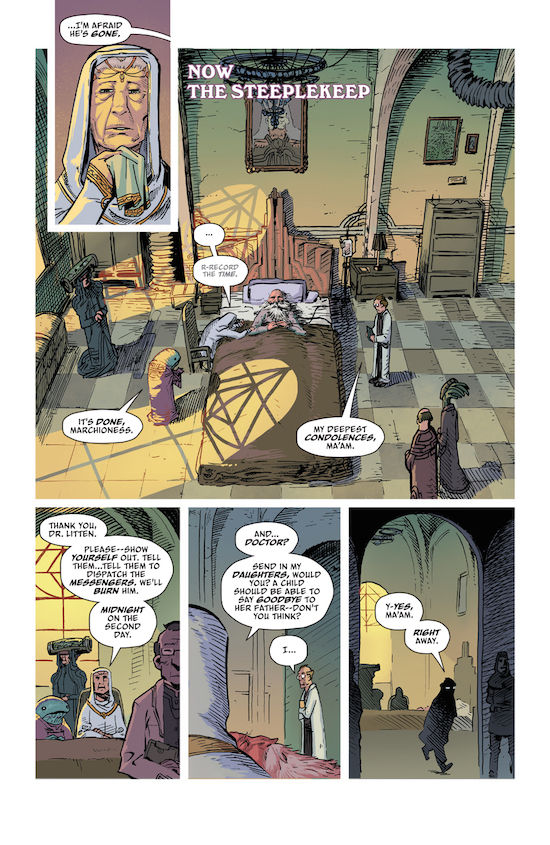

Simon Spurrier, Jeff Stokely and Andre May, The Spire #1 (Boom! Studios)

“It’s the bloody Spire… half a million people squashed into a monolithic dungheap in the desert.”

That quote from the story sums up this new sci-fi fantasy from the pen of prolific 2000 AD and Marvel writer Simon Spurrier in 20 words or less, but there’s so much more going on here beyond the intrigue of the setting, a towering molehill citadel of high-rises crammed together in Victorian squalor. Shadowing Captain Sha of the City Watch, a hard-bitten woman with mysterious shape-shifting powers and strangely no will to repair her missing eye, we move between castes of strange and unusual creatures, who at their lowest are known as ‘Skews’ – or ‘The Sculpted’, to use the more politically correct term for “the backbone of the lower-tier economies”.

Investigating the brutal murder of the new Spire-Baroness’ governess in a squalid district, Sha moves through Spurrier and Stokely’s impressively detailed rendering of this dystopian “progressive and cohesive community” in the first episode of a series which folds in references to power and inequality which find their mirror in the world off the page. – David Pollock

Ales Kot, Matt Taylor, Lee Loughridge, Clayton Cowles and Lee Muller, Wolf #1 (Image)

In the hills above Los Angeles, a burning man wanders the night singing Robert Johnson. The next day he doesn’t seem too bothered about what went on, but he wants to know who filled him full of Rohypnol at a club and lit him up. This is Antoine Wolfe, paranormal investigator for hire, sufferer of the curse of immortality and ex-marine who talks to his dead buddies like they’re there with him. And maybe they are.

Welcome to enfant terrible of the comic-writing business Ales Kot’s tale of an LA infested with an underbelly of supernatural creatures – some of them filled with intrigue, like the girl called Christ being ferried by the police away from a slaughter in a mansion, and some a bit too on the nose, like Antoine’s Cthulhu-esque slacker buddy Freddy Cthonic. This first episode is like Buffy the Vampire Slayer told in the style of Breaking Bad, with a lingering, nicely-played noir creepiness and welcome political undertones which are typical of Kot.

“The strongest story survives, some would say – the one with most teeth,” says Reagan-loving racist crook Sterling Gibson, who Wolfe takes an almost certainly fatal job from, a one-liner which narrows the gap between the myths we all know and the ones which are silently, consciously built all around us by the powerful. – David Pollock