It’s August, and the undoubted comics highlight of this month is Safari Festival on Saturday August 27th at Protein, EC2A. Organised by Breakdown Press, this free event has a stellar lineup of artists. People we’ve featured in this column include Alexander Tucker, Simon Moreton, Simon Hanselmann, Joan Cornellà, Jack Teagle and Matt Swan, but this is just a fraction of the exhibitors. There will be DJ sets from Alexander Tucker and tQ’s own Mat Colegate, and an after party at the Shacklewell Arms. You can get the full details on the Breakdown Press website.

I also came across a copy of Save Our Souls magazine, a comic sized publication with short essays and comic strips by a wide range of people, including a couple we’ve reviewed, Katriona Chapman and Eleanor Davis. It’s definitely worth a look if you come across a copy.

And so, onto the comics.

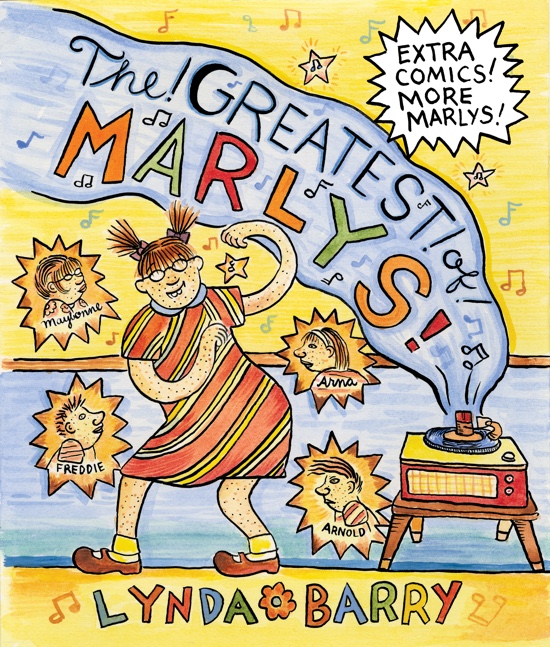

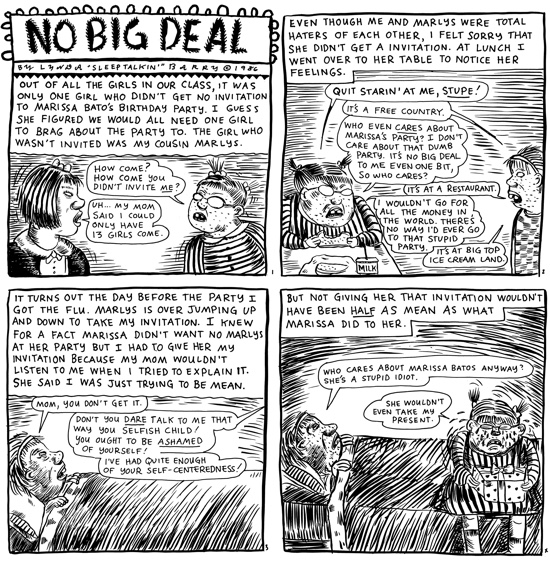

Linda Barry – The Greatest of Marlys

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Drawn & Quarterly recently acquired the rights to Linda Barry’s The Greatest Of Marlys, and their new edition certainly does justice to this most excellent book. It’s a sumptuous hardcover, printed on thick white paper, at least three times the size of my old paperback copy. This definitely deserves the extra shelf space, and is a perfect introduction to Barry’s work. It’s a collection of strips from her long-running serial Ernie Pook’s Comeeks drawn between 1986 and 2001. Marlys Mullen is an eight-year-old girl living in a trailer park surrounded by family more than friends. Most of the strips are from Marlys’ point of view, but we also get to hear from her teenage sister Maybonne, her brother Freddie and cousins Arna and Arnold.

Linda Barry is an extraordinary talent, with a real gift for creating utterly believable child characters. Marlys is so well written that you end up feeling like some of these things happened to you, regardless of how different your childhood was. Of course, many of the events depicted are pretty universal. Barry perfectly pins down the cruelty of other children, the frustration with parents, the complicated love-hate relationships with siblings and relatives, the quirks of teachers, the logic of children and so much more. Her characters show the innocence, the insight, and the obsessions of children in an unsentimental way to which we can all relate, based on our own experiences.

If you already have this book, the new edition is a worthy upgrade, with a couple of new pages (including an introduction) and a massive quality improvement. If you don’t have it, then you’re in for a treat as this an undeniable classic, a huge and truly essential book by one of the most gifted cartoonists we have. The Greatest Of Marlys is a brilliant creation by an equally brilliant creator. Pete Redrup

Simon Hanselmann – Megg & Mogg in Amsterdam

(Fantagraphics)

I’ve sat down with my kids and watched old episodes of Meg and Mog on Youtube. I’ve got books out of the library to read to them. However, for once I was glad my review copy of Megg And Mogg In Amsterdam came as a PDF as it’s less likely to be accidentally discovered, and to lead to lots of questions I’m not ready to answer yet.

If you’re not familiar with Megg and Mogg, they are emphatically not the same as Meg and Mog. On the surface, witches and cats, sure. The challenges they face, however, are not the same. Both are depressed drug users struggling with life. Their friend owl – much straighter – isn’t much help, and Werewolf Jones is a car crash. Typically it’s Owl that always ends up bearing the brunt of Werewolf’s chaotic life, in part as he’s the one with a job. The most interesting dynamic is between those two – Werewolf Jones’ remorse frequently turns to self-loathing and a temporarily sincere but ultimately hopeless desire to make amends. Everyone is permanently red eyed, and the rare smiles to be found are usually gone by the next panel. The level of nihilism here is genuinely astonishing, and yet it’s incredibly funny. At the same time, the characters are all very interesting representations, each believable in their own way. There’s real skill at work in both the writing and the art, and it’s full of deft pop culture references, from Seinfeld to Gamergate.

There’s much more to this book than just a trip to Amsterdam – a good deal of the action takes place at home. When they do arrive in the fabled Dutch city, however, it’s pretty predictable that depressives with easy access to strong drugs are going to find it’s less of a dream than anticipated. The events are entertaining and drive the narrative, but it’s the characters that are the real strength here.

Actually, I lied about being glad my copy was a PDF. Two days after I finished it I read it again. This is a brilliant book, and I’ll be buying a print copy next time I see it, but making sure it lives on a high shelf. Pete Redrup

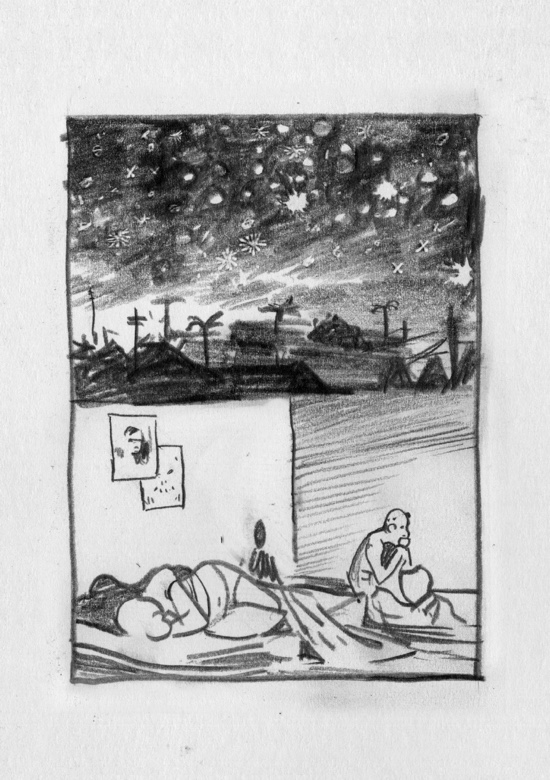

Sam Alden – It Never Happened Again & New Construction

(Uncivilized)

I’ve been wanting to review some of Sam Alden’s work for a while, and Uncivilized were kind enough to send me copies of It Never Happened Again (2014) and New Construction (2015), companion volumes each featuring two stories, both as beautifully designed as expected from that imprint.

It Never Happened Again begins with Hawaii 1997, a wistful yet sharp tale of adolescence, with a faultless ending, something Alden has a particular aptitude for. The art is smudgy and very loose, but completely effective in conveying that period of life, the uncertainty in the face of meeting someone older, more confident, sophisticated (she’s from New York, he from Oregon). Most of the work is done by the art, as there is very little dialogue throughout, and it’s more than up to the challenge. We also get many examples of his drawings of night skies, which are superb throughout these stories, and grace the cover of this book. The second story, Anime, is much more dialogue driven, although the storytelling is quite minimal, and Alden has the confidence not to spell out everything. The art is a little more refined than before, but very similar, and still functions brilliantly. He expertly evokes teenage unhappiness, and his drawings of angry or unhappy people stand out as particularly convincing.

Published a year later, New Construction brings a cleaner, thinner line, with a little more precision. Backyard is an interesting story, well told, with completely believable characters. It’s set in a house of anarchists, and explores a genuinely interesting dilemma from the point of that philosophical perspective. Household is more controversial, themed around two siblings and their differing memories of childhood. The darkness builds with inevitability, and events are subtly signposted, with a coda providing an interesting emotional impact.

Reading these two books together reveal several things. Firstly, Alden is hugely artistically talented. He draws images that effortlessly convey the feelings of his characters, through body language, backgrounds and more, meaning his stories are inhabited by people we believe in. Secondly, he’s an equally skilled writer, with an economy of storytelling that I love. He’s gifted at creating atmosphere, and also at picking poetic, perfect endings. Thirdly, he’s developing fast, and clearly has great work ahead of him. These two volumes are unmissable. Pete Redrup

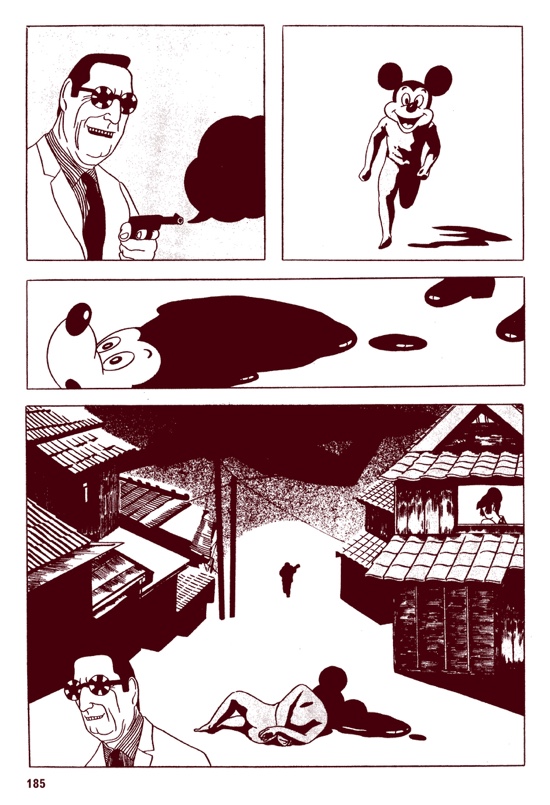

Hayashi Seiichi – Red Red Rock

(Breakdown Press)

Breakdown Press have outdone themselves with the presentation of Red Red Rock. It’s a large, crisply printed volume with thick glossy covers and French flaps. The front in the Western sense is titled Hayashi Seiichi’s Pop, and is the conduit to uber translator Ryan Holmberg’s heavily footnoted introductory essay, giving the air of an academic publication. The front in the Japanese style leads to the manga, and between the two sections is a series of glossy reproductions of posters and the like that Hayashi produced.

This is not an easy read. Open the front, and Holmberg’s essay wonders if you’ve turned here for help. Scoff, turn to the back and the first manga presents little difficulty (when you return to the essay, and you will, you’ll find this was very early work, quite undeveloped). The Devil, His Son, And The Uneatable Soul introduces you to the unique, brilliant presentation where the striking art is matched with Holmberg’s deeply hip translations through exceptionally well executed typography. The second story, however, firmly puts you in your place. There are so many reference points – traditional Japanese culture, 60s counter culture, and of course the response to America so prevalent in manga from this period – that unless you are as erudite as the translator and essayist, you’ll miss plenty. However, there’s still a lot to enjoy first time through, and this is a book that not merely repays but requires rereading.

The manga here are unlike any I’ve read before. I was immediately reminded of the film Tokyo Drifter but not of anything I’ve read. Whereas the gekiga of Tatsumi Yoshihiro and Tsuge Tadao are quite literal in their depictions of life, this is much more symbolic and abstract. It’s concerned with the bigger picture in a pure sense, rather than how the bigger picture is reflected in the smaller life. The voice is often to camera, so to speak, rather than from characters to each other. Hayashi is obsessed by and scornful of American culture, but also focuses on the role Japan played siding with its former enemy taking part in military action against Vietnam, for example, and is critical of the Japanese idea of obeisance to the wishes of employers. There are too many strips here to pick out many, but the epic (yet apparently foreshortened) Flower Poem is one of the most astonishing in this book where nearly everything is extraordinary in one way or another.

This is a remarkable book, a reverential presentation of a unique artist at the height of his powers. Miss it at your peril, but don’t expect it to give up its riches easily. Pete Redrup

Andy Poyiadgi – Veripathy

(Self published)

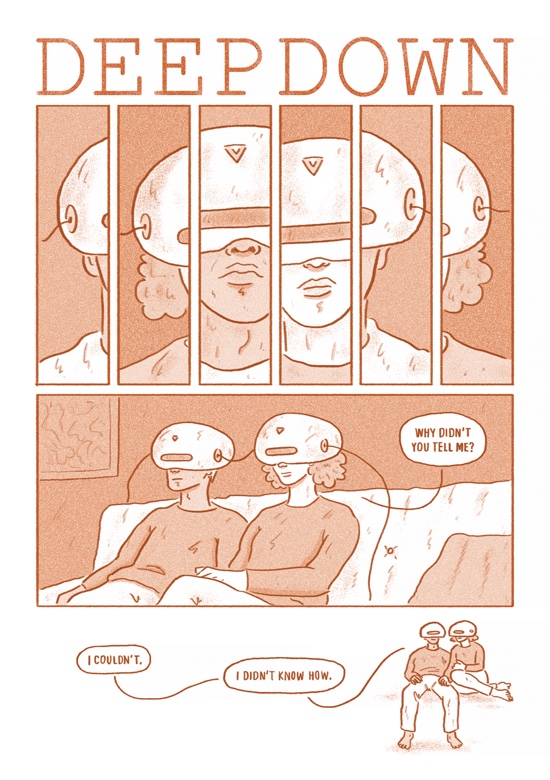

Andy Poyiadgi’s Veripathy caught my eye at ELCAF with its clean, crisp cover. Inside the slim, digitally printed volume are several connected short stories. Veripathy is the process of directly experiencing the feelings of another person, made possible by the use of a veripathic communicator, a device that sits atop the head like a VR headset.

Although a short comic at just 16 pages, it’s far from insubstantial. There’s a minimalism here, with most pages featuring just one or two colours, and with only one story reaching a third page. What Poyiadgi achieves is breadth rather than depth – we see the impact of veripathy across many areas of life. He portrays various medical applications, and also the impact on relationships and social interaction. It’s pretty easy to imagine how addictive it might become to be able to genuinely experience the feelings of another person. Of course, this can be read as an analogy for how many of us find we are permanently plugged in to our phones and the internet, how we choose to connect (or not to disconnect) making it harder to be in the moment, as well as what might happen if VR technology becomes mainstream.

Poyiadgi portrays mostly positives but also some negatives in the exploration of a genuinely interesting idea. The pared back artistic style matches the less emotionally direct narrative in comparison, for example, to his excellent Teapot Therapy. This works really well for a comic that is about possibilities rather than loss. This is a really impressive, coherent work from a highly talented artist. It’s available in Gosh! and Orbital, and also from Poyiadgi’s online shop. Pete Redrup

Una – On Sanity

(Self published)

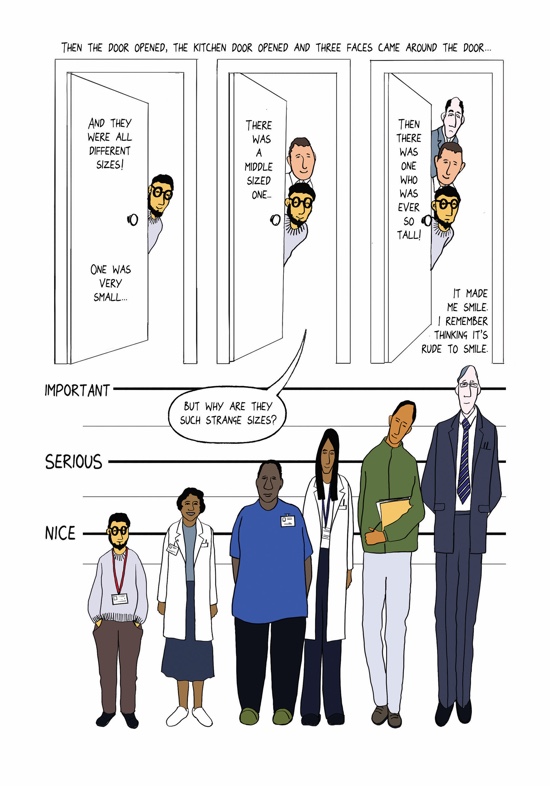

Mental health is such an important topic, and yet one that we do not hear enough about. The media can be deeply unhelpful, only tackling it in the case of some terrible crime, forming associations that do not reflect the vast majority of mental illness and only compound the problems unwell people face. This short, self-published comic by Una (whose Becoming Unbecoming is one of the most moving and powerful books I have ever read) focuses on the day her mother was sectioned, and includes accounts written by each of them and then illustrated by Una.

One thesis of the book, stated on the first page, is that treatment needs to be more than just pharmaceutical. The first section, Una’s, was written in 2008 at the time of the events. The second takes the form of a conversation, almost an interview in places, as Una and her mother look back. We get to hear about her state of mind, and the delusions she was experiencing, and also about how she has recovered. What’s pretty clear is that this was a very valuable intervention, instigated by her family, and how there have been many positive outcomes.

As with Una’s other work, she varies the styles of image considerably. Quite a few feature top down plans tracking movement through rooms, whilst others have more conventional panels. The combination is distinctively hers, and works well. This is a brave, honest book, where two people share a deeply private time in their lives. I’m sure there’s an element of catharsis here, but more strongly it’s a piece of public service.

You can buy this from Una’s website and also OK Comics and Travelling Man in Leeds, Travelling Man in York, Page 45 in Nottingham and Gosh! Comics. Pete Redrup

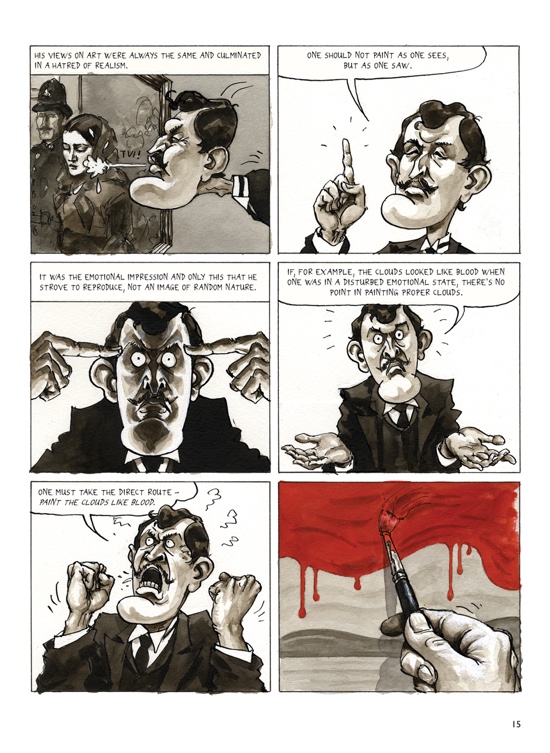

Steffen Kverneland – Munch

(SelfMadeHero)

Steffen Kverneland’s graphic biography of Edvard Munch is astounding. Kverneland’s energy, passion, knowledge, and drive fly off every page, holding us spellbound within the book. Even if one (as did this reader) knows nothing of the artist’s life beyond the fact that he painted ‘The Scream’, the art and story are so fascinating, so captivating, one cannot possibly put it down. And just such magical forces permeate Munch’s life, along with that of his friend Strindberg, whose own story is also given a good account here. Much is made of their drunken, occult circle – international poets, artists, writers, and dancers gathering at Zum Schwarzen Ferkel (‘The Black Piglet’) in Berlin.

Munch took Kverneland seven years to complete and the great care and work involved in the project is evident in every panel. Determined to tell the story via the voices of those involved, Kverneland keeps himself to authentic quotes from the time. Thus we hear from Edvard Munch’s letters, diaries, notes, and of course graphic works, as well as the writings of Munch’s family and friends, and many other critics and acquaintances. Kverneland himself appears in the story when he chooses to offer his own thoughts or show his researching.

Along with this wide range of source material, the artwork is magnificent, ranging from Naturalism and Impressionism to Symbolism and Expressionism (with some hints of Futurism), as well as Photorealism when the author introduces himself into the text. And so we are given a wondrous view of Munch’s life as he sought to depict the emotions behind what was seen, and all the angst and illness involved in doing so. Aug Stone

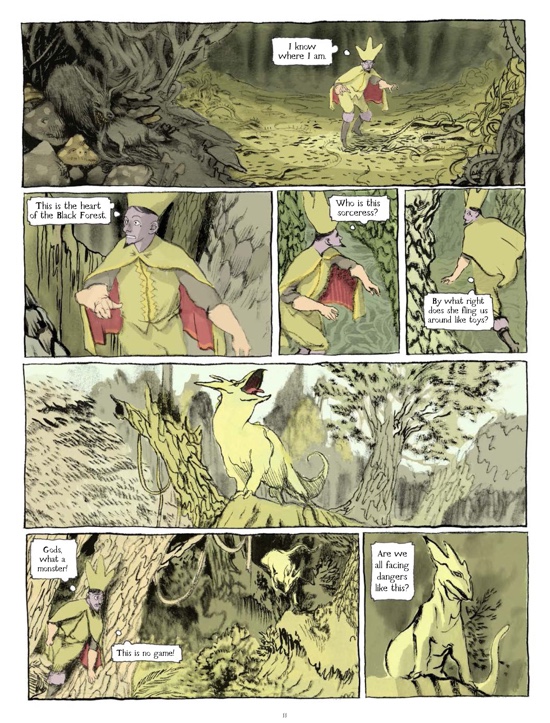

Alexis Deacon – Geis: A Matter of Life and Death

(Nobrow Press)

Alexis Deacon began his career in illustration and children’s books gaining numerous awards and accolades for over a decade. In recent years, Deacon has begun a steady transition into the world of comics continuing to earn recognition for his stunning work. In 2014 he won the Observer/Jonathan Cape/Comica Graphic Short Story Prize for his comic The River, and in 2015 he re-imagined legendary author Russell Hoban’s story Jim’s Lion into a long format children’s book utilizing many elements of comic book storytelling. Now in the midst of a trilogy beginning with Geis: A Matter of Life and Death, Deacon tells a story of magic, adventure, and equality in his debut graphic novel.

A geis, pronounced ‘gesh’, is a Gaelic word meaning an unbreakable taboo or curse. Unfortunately for the fifty souls vying for the throne in Geis: A Matter of Life and Death the curse binding them comes with an unknown price. The book begins when an assembly is called after the death of the chief matriarch Matarka. Without an heir, Matarka created an enchanted will, which when signed enters the person into a contest consisting of three trials. When the last signature is collected a sorceress teleports the competitors into the furthest regions of the kingdom, giving them until dawn of the next day to find their way back to the castle. The first to return are Io and Nemas and are therefore rewarded with the deadly truth. Only one competitor can survive all three trials in order to become the new chief, and any who fail to reach the castle gates by sunrise will be the first to die. An additional twist of magic prevents Io and Nemas from sharing this knowledge with the others, quickly defining the actions of these characters.

Deacon inserts every panel with rich depth, and uses atmospheric perspective to a level I have not seen accomplished by any other artist. He often blurs elements either in the extreme foreground or background, focusing the reader’s attention on the most important subject of every image. His muted color scheme is perfect for describing a world of enchantment, and despite the large ensemble Deacon’s carefully considered character design makes each member of the cast instantly recognisable.

The most refreshing aspect of the story is the impressive number of female leads including, the dying matriarch, an evil sorceress, an elderly librarian, a judge, a priest, a magician, and the protagonist Io. Having women in both villainous and heroic positions gives the book a complexity I had not expected, and I hope that we continue to see more balanced roles for men and women in comics. Sword and sorcery is not my typical genre, but I found myself quickly ensnared by Io and Nemas’ secret, and can’t wait to see what happens next. Matthew Laiosa

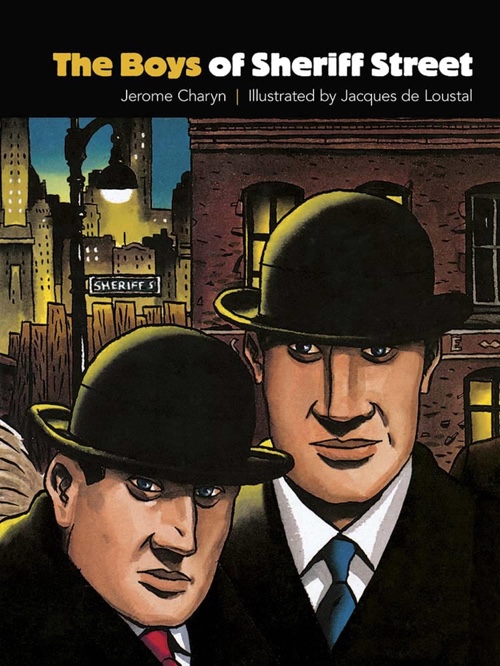

Jerome Charyn & Jacques de Loustal – The Boys of Sheriff Street

(Dover Publications Inc.)

Last December I had the pleasure of interviewing Jerome Charyn about his sprawling career in prose and comics. Learning how to read from comic books, and a long admirer of the medium, he finally became a full-fledged comic author after contacting a French editor for a story titled The Magician’s Wife. The book won the Grand Prix award at Angoulême in 1986, and was published in the U.S. by Catalan Communications. Despite Charyn’s early success, many of his comics have been out-of-print for over twenty years. Fortunately the modern craze for graphic novels has lead Dover Publications to re-release and newly translate many of Charyn’s overlooked works.

Spending a major portion of his career writing crime novels, Charyn treads familiar territory with The Boys of Sheriff Street, but that is not to say that the book is at all familiar. The story set in 1930s NYC features twin brothers, Max and Morris, and their dueling infatuations with a beautiful movie theater ticket taker named Ida Chance. When Morris announces his engagement to Ida, the hump-backed Max becomes quickly consumed by passion and violence. Unable to cope with his jealousy he leads his gang into a war with their rival, Leo Whale, causing irreparable damage to himself, his brother, and to the woman he can’t bear to see in another’s arms.

In the introduction Charyn says unlike most comic artists who attempt to create movement through static imagery, Jacques de Loustal captures ‘the solitary images of a dream,’ although nightmare might be a more apt description. His images, like the nightmare cartoons of George Grosz, are filled with an emotional energy that would be much harder to convey in a film or book. The muted earth tones, and nauseating yellows and greens perfectly reflect the loneliness, despair, and unrequited lust of Max. My only wish is that the images were allowed to speak for themselves more often. The book uses many captions that often describe the images without adding additional meaning. Noir is famous for its narration and internal monologue, but in this case the narration sometimes robs the reader of their own interpretation.

Even though the narration is at times tedious, the book is worth if for the one-of-a-kind world it creates. Instead of depicting a realistic world of crime, Charyn and Loustal portray a mythic world, a world of self-made gods as petty as their Greek counterparts, a world of deformed monsters, hopeless romantics, and seductive sirens. This is Greek tragedy at its best dressed in trench coats and derby hats. NYC stretches into the sky like a grotesque Olympus and the interiors of train stations, cafés, and movie theaters are like the cavernous depths of Tartarus. Charyn, a novelist, and Loustal, a painter, prove that the graphic novel medium is the perfect marriage of both literature and fine art. Matthew Laiosa