Audrey Golden opens Shouting Out Loud by rejecting a premise most biographers accept without question: that any single account can claim definitiveness. Her methodology instead builds toward something more useful: a history constructed from voices that standard rock narratives systematically exclude. The result demonstrates what becomes visible when you start listening to people who were actually there, but who were never asked.

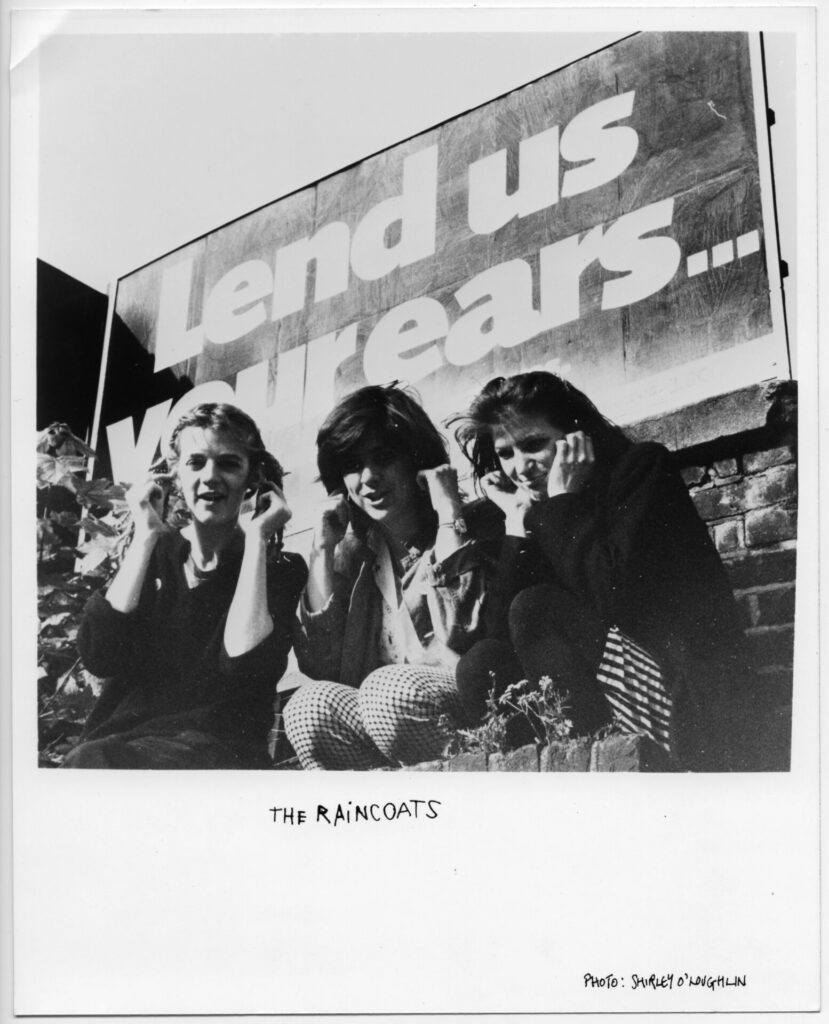

This approach was first developed in her earlier book on Factory Records. While researching I Thought I Heard You Speak: Women at Factory Records, Golden found that women who ran the label’s day-to-day operations were either unnamed or misremembered in existing accounts. Bringing their testimony forward didn’t merely add detail but changed the subject. As Raincoats manager Shirley O’Loughlin told her, everyone remembers events differently, and those differences matter. The principle that memory is subjective, contradictory, and still historically valuable shapes the book’s entire methodology.

For Shouting Out Loud, this method is adapted while moving beyond strict oral history. The book synthesises nearly two hundred hours of interviews with around one hundred people alongside archival research, fan letters, underground publications, and Ana da Silva’s personal archive. Golden narrates, but her voice functions more like a conduit than an authority, guiding readers through other people’s experiences rather than imposing coherence on them.

The limits of memory are made explicit: interviews are shaped by the questions posed, accounts conflict, and recollections shift over time. Rather than smoothing over these tensions, Golden leaves them visible. Some details may contradict what readers think they know; others may surface nowhere else. It’s a deliberate refusal of false certainty.

This refusal matters because exclusion from music history is structural. Golden traces how The Raincoats’ music found its way to political prisoners in Belfast’s Maze prison, Polish anti-authoritarian activists, and Turkish feminist organisers – mapping routes of influence that bypass official channels entirely. Prison letters, benefit gig flyers, and zine references become crucial evidence. Culture, the book suggests, travels sideways: hand to hand, outside the sanctioned frame of the music press.

Fan mail plays a central role in demonstrating this archival commitment. Voices like Anita Chaudhuri emerge: a mixed-race teenager who wrote to The Raincoats in 1979, isolated at school and finding connection through their cover of ‘Lola’. Twenty-five years later, Anita revealed this was the only fan mail she’d ever sent:

“I’ve reached the ultimate in tedium… Ten year old boys stand in clichés outside the ‘hip’ record shops of the week, in their denim jackets with ‘Sex Pistols’ patches sewn on the back by loving mothers. Or if they’re really sussed then they wear Crass T-shirts and UK subversive armbands. I feel very ill. Excessive crows clad in parkas + black and white mini dresses are also beginning to annoy me… They all look stupid in exactly the same way.”

These documents matter as evidence of how music functioned for people whose experiences rarely appear in official histories. They show how young women articulated feminist consciousness through responses to The Raincoats’ work, often before having the language to express those ideas formally.

Golden’s cast of interviewees extends far beyond the band. We hear from the Polish activist who smuggled guitars into Warsaw, the loyalist prisoner writing from jail, the queer Canadian zinemaker coding Raincoats songs as survival signals, and the choreographer who turned ‘Shouting Out Loud’ into protest performance. The chapter on queercore documents how G.B. Jones and the J.D.s community identified queer possibility in songs like ‘Only Loved At Night’, using The Raincoats’ music to build transnational networks during the AIDS crisis. Within these networks, music became a means of connection where mainstream culture was absent. Treating these figures as historical subjects rather than colourful footnotes carries political force. Power operates through historiography itself; the question isn’t just who gets included in music history, but whose experiences are recognised as constitutive of that history.

This approach mirrors The Raincoats’ own commitment to experimentation and collaboration. Linear tidiness is resisted; connections are followed as they emerge. Warsaw leads to Belfast, Belfast to Toronto, Toronto to Istanbul. A chapter may move from recording sessions at Matthew Wood’s studio to a teenager’s letter, then forward to that teenager’s later life as a journalist. The sprawl reflects how influence circulates: unevenly, unpredictably, through unlikely intermediaries.

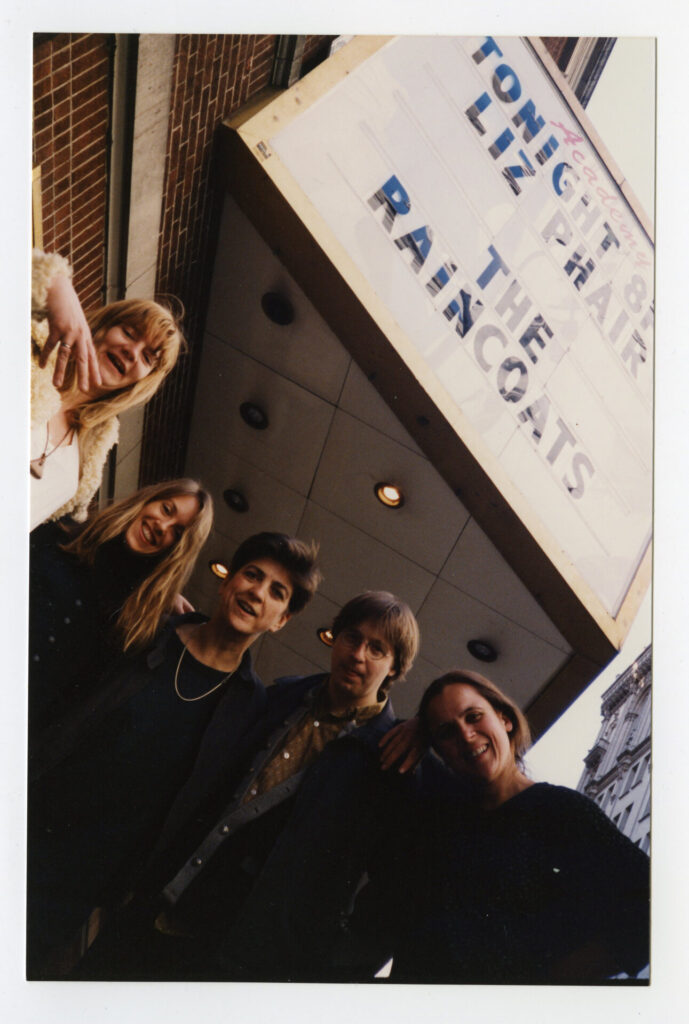

The band’s career divides into three lives: their late-1970s emergence and mid-1980s dissolution; their 1990s revival sparked by Kurt Cobain’s advocacy; and their 21st-century reappearance as elder stateswomen performing in museums. Each phase is treated with equal seriousness. Early Rough Trade recordings carry no more inherent weight than MoMA performances; Nirvana support slots matter no more than contemporary protest work. Origins are not privileged over aftermaths.

Golden’s previous book faced predictable resistance. James Nice, whose own book on Factory Records has been marketed as “definitive,” reportedly asked, “Who’d want to read that?” when hearing about the project. His publisher recently reissued his work, doubling down on the “definitive” label. This reaction illustrates exactly what Golden argues against: the assumption that accounts centred on male executives and musicians are complete, and that nothing of consequence lies outside them. The claim of definitiveness isn’t about completeness so much as control. Golden continues to find the voices left out and makes visible how authority itself becomes a form of gatekeeping.

The Raincoats emerged from the political convergences of late-1970s London: DIY punk ethos meeting Rock Against Racism and Rock Against Sexism. Golden captures how Ana da Silva and Gina Birch, art school graduates with minimal musical training, intuited punk’s democratic promise while fashioning something entirely their own. Early Rough Trade recordings transformed technical limitation into aesthetic choice; four women learned to play as they created.

The book is particularly strong on the band’s relationship to feminism, showing how politics were articulated through musical practice. Collaborations with Robert Wyatt and the reimagining of The Kinks’ ‘Lola’ show how covers could shift perspective and power, excavating new meanings from familiar materials. Then there’s ‘Off Duty Trip’, which addresses rape by British soldiers in Northern Ireland – delivered without cushioning or poetic distance.

The Raincoats’ liberation from corporate culture carries new resonance today, as neoliberalism reshapes who gets to make art at all. Golden documents how the band operated entirely outside commercial imperatives – rehearsing in squats, self-releasing records, touring on minimal budgets – creating a blueprint for cultural production that required neither institutional permission nor private wealth. The DIY ethos was a survival strategy, not romantic primitivism, and it reads with renewed urgency in an era when streaming economies and prohibitive living costs make working-class participation in music ever more difficult. As Lois Maffeo tells Golden, The Raincoats demonstrated liberation not just from corporate culture but also from patriarchy, religion, the military, and expectation itself: making music and making magic out of nothing as fundamentally political acts. The lineage running from ‘No One’s Little Girl’ through Riot Grrrl to contemporary DIY networks is a continuous thread of refusal. When The Raincoats insisted you could make your own rules, they were documenting how to build culture when all sanctioned routes are inaccessible.

The book’s middle section examines how influence travels through underground networks. Kurt Cobain’s invitation for The Raincoats to support Nirvana registers as recognition between kindred spirits: two groups committed to expanding rock’s emotional range while unsettling its masculinist assumptions. Nostalgia is sidestepped when addressing The Raincoats’ 21st-century afterlife. Appearances at MoMA and the Pompidou Centre feel like a continuation of a boundary-dissolving practice rather than a departure from it. Interviews with Bikini Kill, Sleater-Kinney and Big Joanie trace the band’s ongoing influence across generations, grounded in demonstrated possibility rather than imitation.

The book makes a case for methodological humility in music writing. Strong storytelling, Golden suggests, can accommodate uncertainty. The implication is simple: histories improve once writers begin listening to voices previously excluded. Shouting Out Loud captures what made The Raincoats genuinely radical – their expansion of rock’s emotional and sonic vocabulary through practice rather than prescription. It returns that history to the centre, arguing that some stories resist closure precisely because they remain unfinished. Golden gets to the heart of it in her conclusion: keeping your own time means it’s yours to define. The Raincoats built that permission into every song they recorded, and they extend it to everyone still listening.

Shouting Out Loud: Lives of the Raincoats by Audrey Golden is published by White Rabbit