There may not have been a comics column on tQ for a while, but there have been comics, and here are some of them.

Tillie Walden – Spinning

(SelfMadeHero)

Spinning, Tillie Walden’s largest book so far, is her first not to come from Avery Hill (they’ve got the next one, though, the print edition of her recent webcomic On A Sunbeam). It’s a memoir of her adolescence framed through several years as a competitive ice skater. She presents herself as shy, prickly, keen to fit in and nervous that she won’t.

Unsurprisingly, the book shows the dedication required to be a competitive skater, the early starts and practices that wrap the school day, leaving little time for anything else. Woven into the skating is her emerging sexuality; early on she talks about having realised she was gay aged five. In a sense, it feels like her first two books were circling around elements that she is now more confident to directly explore with herself as the subject. The scale of the ice rinks and the malls she moves through evokes the large spaces of The End Of Summer while an early relationship looks much like the one explored in I Love This Part.

The art is mostly purplish-black and white with shades of grey and bursts of occasional yellow. I don’t know if it’s simply the way Walden draws her facial expressions, but we don’t get any sense of a strong passion for the skating. A desire to succeed is evident but it feels more like she wants to do well at whatever she does rather than that what she does is the thing she wants to excel in.

This is a strongly female-focused story, with lots of female teachers and coaches, as well as peers, some friends and some bullies. Her father and twin brother are pretty much the only male characters, apart from a sleazy SATs tutor. She does not hold back in her delineation of her familial dynamics and appears to have a tense and distant relationship with her mother. As her commitment to skating wanes, she develops an interest in art. Whilst I’m always keen to avoid spoilers, Walden is very well known as a cartoonist, not a skater, moreover a cartoonist with such a prodigious output that it’s hard to imagine she even sleeps let alone has time to maintain skating. We’re left assuming that the work ethic she developed as a skater, the 4AM starts, training before and after school, is what sustains her cartooning.

This is a simple story of someone following a passion that they aren’t sure they actually feel. Walden is constantly trying to find out who she is as she changes, as she comes to terms with how her sexuality affects her relationships with others. The sheer size of the book prevent it from achieving the same simple elegance of I Love This Part but it is considerably more emotionally engaging than The End Of Summer. It’s a very accomplished work and an impressive edition to her catalogue. Pete Redrup

Alex Potts – It’s Cold In The River At Night

(Avery Hill)

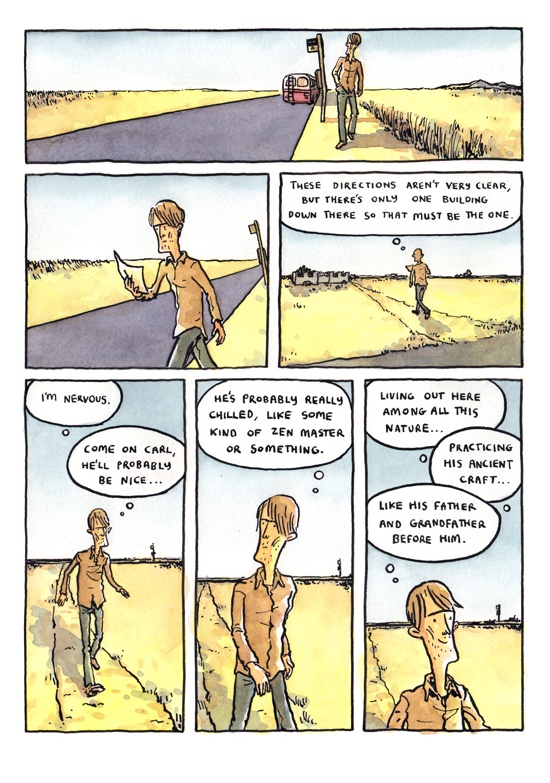

Alex Potts has had plenty of strips included in anthologies over the last few years, but It’s Cold In The River At Night is his first longer story since 2014’s A Quiet Disaster. Anthologies serve a vital role in bringing artists attention, but very short pieces are often less satisfying than longer ones, so anticipation is high for this full-length book. Various Potts trademarks are immediately evident: a thick line supported by gentle watercolours, a central character with a head like an inverted butternut squash, and a witty and gently (self-)mocking tone.

Carl lives with Rita in an isolated house on stilts. She’s studying, while he is drifting, much like the boat he ineptly tied to the mooring post of the house. There’s a sense of his avoiding the important stuff, while Rita works hard on her thesis. Rooted in a sense of an earlier time, he’s interested in the history and traditions of where he is living and in particular, unusual boat-shaped coffins that appear to be a local specialty. Carl is very insecure in his masculinity and wants to address this through hunter-gatherer behaviour, and working with his hands. He feels threatened by other men, such as Mr Beuf the landlord and later, the local coffin maker, who he hopes will transform him with little consideration of whether his would-be guru might want that.

Avery Hill have a hit rate few publishers can match, with an ability to spot talent and to allow artists to produce their best work. This book is no exception. Carl is a gloriously solipsistic protagonist, who can quickly move from rejection to rumination on the futility of existence, which is then worsened by the arrival of rain. Potts has created a curiously distant world – beyond the existence of a laptop, there is no real evidence that the book is set in the present. The location is unspecified beyond Western Europe. People, buildings, vehicles all look old, and the colour palette reinforces this idea with its muted tones. His distinctive sense of humour is well matched to his artistic style, and he pushes his narratives in directions I can’t imagine many others taking. Potts rarely feels the need to wrap things up with a neat ending where everything works out just fine, and It’s Cold In The River At Night is all the better for that. Pete Redrup

Marinaomi – Turning Japanese

(2dcloud)

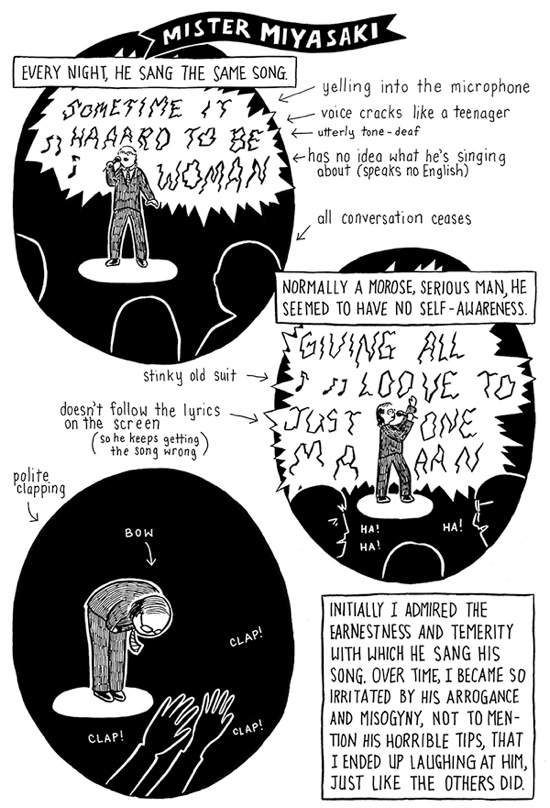

Marinaomi’s Turning Japanese is an autobiographical work with a very specific focus, covering a period in the mid 1990s when the author was preoccupied with her search for identity as a Japanese American. It takes in a short spell working as a hostess in a Japanese bar in San Jose, and then an extended trip to Japan with more of the same work, and family visits, accompanied by her American boyfriend Guiseppe.

The book’s clean pages are filled with simple black and white line drawings. There’s considerable variety in page layout, from sparse full-page panels to six-by-seven grids, and this works well, letting the reader zoom in to the detail or pull back to the bigger picture as appropriate. This, and the compact but thick hardcover format, make it a tactile and appealing book.

There are numerous references to her upbringing, and the fact that her mother did not teach her Japanese and will rarely speak to her in anything other than English. Working in a hostess bar brings greater insights into Japanese culture, but also a deepening sense of unease that she’s betraying her feminist ideals working as a hostess. She is baffled by the sense of familial responsibility of a fellow hostess, returning to her hated childhood home to take over the family business, despite having been abandoned by her parents as a child. Yet, when she visits her grandparents, Marinaomi finds herself eager to please them in a way Guiseppe finds surprising. This part of the visit also gives insights into her mother’s character, and familial traits across three generations. As she learns more about herself, a distance grows between Mari and Guiseppe. As she learns more Japanese and deepens her understanding of the culture, Guiseppe becomes increasingly isolated, unable to work, with no money to spend, and no-one to talk to.

This is an excellent piece of autobiography, where the blend of narrow, personal focus and skilful art draws the reader in, rewarding empathy with insight. Highly recommended. Pete Redrup

Seth – Palookaville 23

(Drawn and Quarterly)

Seth’s ongoing Palookaville series continues with this release, a typically beautiful cloth-bound hardback, instantly recognisable as his work. The first part is a continuation of the autobiographical Nothing Lasts. Compared to the rest of the book, this features relatively uniform panels laid out in a 4×5 grid, and the lettering is a little rougher. Such simplicity and consistency in no way takes away from the creative use of the space. One page is full of drawings of his tropical fish collection, with the oxygen bubbles combining with the text to give the impression the page is narrated by his pets. This time we learn of candidly revealed adolescent sexual urges, and much musing about class. It’s particularly good on the impermanence of memory and the intensity of teenage love, hyper real at the time yet hard to recall thirty years later.

From time to time Seth gives the impression that this is a self-indulgent project, and that the thoughts of his teenage self are too embarrassing to recount. Nonetheless, he draws the pictures and recounts the thoughts. This is Palookaville 23, not Palookaville 1. Seth has long ago proved his considerable worth as an cartoonist, and he’s normally so confident in his line, his story and himself. I think by the time an artist has written and drawn an autobiographical work and we are holding a hardcover in our hands, the author should at least be sure that it was a good idea.

At last, the twenty-year work that is Clyde Fans concludes, returning to 1957. For the first forty-or-so pages, there are few images of Simon Matchcard and none of any other people. What we get instead are landscapes and buildings overlaid with wistful musings, very much the artist’s trademark. Frankly, I could look at Seth’s scenery for quite some time without getting bored, and his depictions of architecture, nature, darkness and space are well worth the price of admission. There are almost no conversations, excepting the brief exchange as a train ticket is purchased, and a couple with his mother. This is Matchcard isolating himself from the world, becoming the recluse depicted in earlier volumes. It’s a melancholy, meditative close to this long-running story, and a fitting end. We can assume that the whole of Clyde Fans will be collected in a single volume, but until then, this will do nicely. Pete Redrup

Nathan Hill et al – The Great Anthologée Hotel

(Hotel Anthology Books)

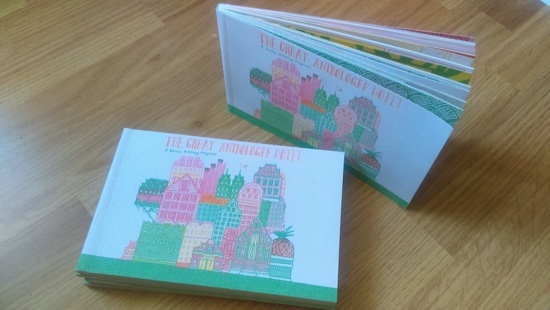

This first volume (which I hope means more is on its way) of the Hotel Anthology magazine is a thing of beauty.

It’s amazing what a nice printing technique and a limited colour palette can do to pull together disparate artists’ styles. Risograph printed in red, green, and yellow The Great Anthologée Hotel benefits from a canny horizontal design theme by Nathan Hill, who also edited the collection. Although Hotel maybe wasn’t the best name choice in terms of search engine optimisation, the theme is a strong one with each story nominally set in a room in this fictional hotel. The definition of room is definitely stretched here to include fantastical plughole dimensions, a beach and really a wonderful variety of portals to other realms.

While a lot of anthologies boast diversity and skill in their line-up, this book genuinely merges some really exciting approaches to storytelling, some very literal and some very abstract. There is not one disappointing entry here and perhaps even more unusually, none of the stories are cynical or moany (although some are certainly bittersweet).

In a few places the green midtone is too pale so that you have to look really closely to read the words or see the delicate drawing, much paler than the red midtone, so while I’m very happy to own my copy of the first print run, perhaps in future runs the risographic ink choice could be tweaked.

As I have stated all of the stories are excellent here, so it’s hard to choose stand-out ones to mention, but here goes: ‘Chicken McGuffin’ by Dan Scarlett made me laugh out loud, balancing the comic timing of a concept that could so easily have been clunky (time travel, and a magic nugget). Both Max Iu’s ‘Chef Da Qian’ and Laura Jusman’s ‘The Holiday’ combine such beautiful standalone page illustrations that I want to rip them out and stick them on the wall, with faultless pacing. Jusman’s work both suffers and benefits in equal measure from that lighter green tone, which is one to think about on the intersection of serendipity and ink intensity. Lastly, ‘Plenty More Shadows’ by Courtney Thomas treads that line between adorable and creepy beautifully with a story of suspicious gifts.

I thoroughly recommend you snap up a copy of this anthology while you can. Jenny Robins

Nagata Kabi – My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness

(Seven Seas, distro by Macmillan)

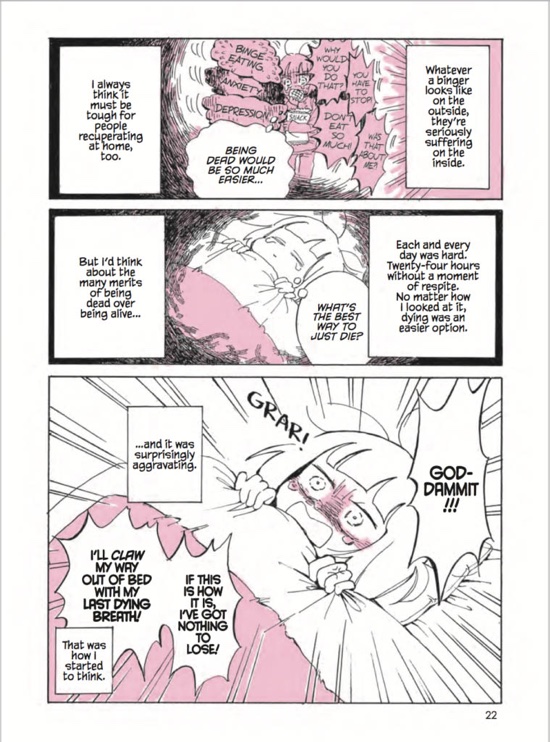

This autobiographical manga originally published by Nagata on the art website Pixiv and first printed in Japan by East Press in 2016 as The Private Report on My Lesbian Experience With Loneliness, has won international acclaim for its blistering honesty – a stark contrast with the hyper romanticized yuri stories that the title and sexual orientation of the protagonist (and author) associate this book with. One might say that said orientation should be – or even is – beside the point in this comic. Really it’s a story about the author coming to terms with her own self-worth and battling through some really serious mental health issues to gain the confidence to pursue a career in comics. But maybe we’re past wishing the world were less interested in labels and more in truth, maybe the only way to find truth is by judicious use and abuse of those labels.

The book begins with the cover image – Kabi poised like a startled cat, crouching at the other end of the bed and faced with a female escort she has worked up the courage to hire, despite being twenty-eight years old and having “never dated anyone, never had sex – and on top of that, never had a real job.” We then rewind to read about the years leading up to this moment of courage and the layers upon layers of doubt and fear, most of which have seemingly little to do with the artist’s sexuality.

The relative permissiveness of the Japanese sex industry combined with the strong vein of reserve and conservatism in the culture are just two juxtaposed ingredients that make consuming manga and other cultural exports a thrilling and popular – if at times problematically exoticising – experience for Westerners. Many of Kabi’s experiences however are very relatable and richly sympathetic – wherever you are reading from. On that basis alone this is a piece of recommended reading for anyone who has ever asked themselves if they have “failed at being a person”. Jenny Robins

Nicole Claveloux – The Green Hand and other stories

(New York Review Comics)

The Green Hand is a gorgeous gem that NYRC deserve much applause for saving from obscurity. A delight for anyone interested in surrealism, Edith Za’s tale of a nameless woman and her roommate, a morose man-sized talking bird, each trying to find themselves and their ways through this crazy world is brought to ultra-vivid life by Nicole Claveloux’s unique artwork and colour palette.

At times, with its large faces and plant growth, Claveloux’s work is reminiscent of Terry Gilliam’s animations with Monty Python, combined with a certain lysergic-ness seen in early days of Les Humanoïds Associés’ comics (who originally published these stories between 1978–1980). But that’s where any comparison ends. Claveloux presents a world that creates itself anew at every moment, where one can fall through the walls – as our protagonist does – into stranger territory still.

These panels contain the familiar yet mysteriousness of dreams. The kind of world one would thrill to be lost in, even willing to pay the small price of fright that some occurrences inspire. And for those paying even closer attention, there are lovely little details that offer pay-offs as the story progresses. The Green Hand is simply wonderful.

The collection is filled out by seven more stories by Claveloux, told through a wide range of styles and offering meditations on murder and family, menstruation, and aspiration. The highlight of these is the excellent ‘The Little Vegetable Who Dreamed He Was A Panther’. Stylish and humourous, ‘The Little Vegetable…’ constantly morphs, all the while resonating with the human condition.

This lovely hardback edition also includes an introduction by Daniel Clowes (a big fan) as well as a four-page interview with both Claveloux and Za. Aug Stone

Matt Kindt & David Rubin – Ether: Death Of The Last Golden Blaze

(Dark Horse Comics)

Simply put, this is one of the best comics in recent years. Matt Kindt’s ever-inventive imagination paired with David Rubin’s fantastic-in-every-sense artwork make this first volume of Ether a treasure to read.

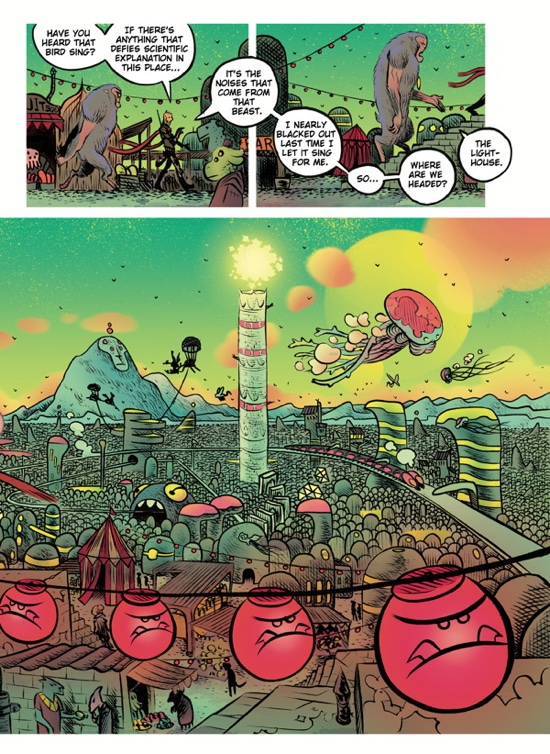

Boone Dias is a hard-boiled realist, an intrepid explorer in the name of science. He’s also the only one who can cross over in the Ether – in his words, a “construct of the collective unconscious” – without going insane. Life in the Ether reminds one of the Arthur C. Clarke quote – “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Boone firmly believes that once investigated properly, all this “magic” will be able to be fully explained.

Kindt does a spectacular job of portraying the idea of the astral world, working in the theories of how to get there and what it contains, without resorting to any heavy-handed occult dogma. In short, it’s great fun.

And the action starts straight away, with Boone arriving at the border between the worlds and the giant purple ape, Glum, gatekeeper of the crossroads, bringing him to the capitol city of Agharta. He’s been called on to investigate the murder of Blaze, the protector of the realm. Here a wonderful play on a well-known conspiracy theory sets off the search for the assassin as Boone and co. travel to some of the Ether’s more chimerical realms.

Rubin’s artwork is excellent all around as the scenes oscillate between Earth and the Ether, and he constructs the latter to be most enchanting, creating no end of new imaginative territories. Although there have been no new issues after the ones collected here, one fervently hopes the series will continue. Like the empyreal world it depicts, Ether’s possibilities seem boundless. Aug Stone

Rich Tommaso – Spy Seal: The Corten-Steel Phoenix

(Image Comics)

If Tintin were reading an anthropomorphic comics adaptation of a James Bond film, it would look a lot like Spy Seal. Tommaso neatly works in references to Hergé (a scene set in a town called Flupke, in Belgium no less, later with a visual nod to The Black Island) and main villain Miles McKeller bears a resemblance to Mr. White of the Daniel Craig Bond films.

The titular seal, one Malcolm Warner, becomes involved in the world of espionage through innocently accompanying a friend to an art opening at London’s Phoenix gallery. Due to his actions after a terrorist attack there, MI-6’s ‘The Nest’ recruit him and soon he’s off to the Riviera for his first mission.

Spy Seal has all the right ingredients for a fun spy thriller – the world of high art, international destinations, suspense, militant factions, and double-agents. And it’s never stated outright, but with communists as the enemy, this seems to be The Swinging 60s.

The artwork is great, very influenced by Hergé and his clear line style. The only problem is that sometimes the characters are unnecessarily wordy, extraneously agreeing with one another or offering too much explanation. So much space given over to dialogue and therefore needlessly large word balloons is room that could be giving us more of the lovely scenery. To emphasize the point, there are occasionally – barring sound effects – consecutive silent pages that really flow and tell the story well enough without any need for words. But thankfully this over-reliance on verbal exposition doesn’t detract too much from the enjoyment of the story – which is, after all, a good read. Aug Stone