If I was asked to draw up a guest list for my fantasy dinner party, the writer, presenter and film-maker Michael Smith and DJ/producer-colossus Andrew Weatherall would definitely feature. Both have had a big and positive influence on my cultural consumption, can talk at length with erudition and listen intently (a rare gift) and would, you’d presume, bring along a decent bottle of claret or two. I first came across Smith’s work when reviewing his 2009 BBC Four series Drivetime, a meditative treatise on driving in Great Britain. Like everything Smith does, including his pieces for The Culture Show, his scripts are packed with nuggets of poetry, crafted with care and full of expression – something sadly lacking in a lot of television documentary scripts these days. He takes this approach into his novels, turning his thoughtful observations into beautifully crafted prose; a luxurious drift of words to nourish the soul.

Weatherall, the artist formerly known as Lord Sabre who now goes by the deserved title of “The Chairman”, has reached 50, and while he may have called time on the hedonism, creatively he is spreading his wings. The publisher Faber and Faber (specifically, Faber’s creative director Lee Brackstone) has brought this pair of kindred spirits together for a project where Weatherall, currently Faber’s Artist in Residence (a nebulous position that he is evidently proud of but unable to pin down precisely what it entails), has provided a soundtrack for Smith’s novel, Unreal City, a work Smith describes as ‘a series of vignettes about London … a dysfunctional love letter to the city,’ and Weatherall nails thus: ‘It’s an ‘It’s not you, it’s me’ letter to [London].’ The narrator of the novel is a version of Smith; a creative fallen on hard times, drifting around East London watching the hipsters taking over his old stomping grounds, reminiscing of decadent nights in old Soho and shabby canalside warehouses in Hackney.

Weatherall has composed the perfect soundtrack for Smith’s melancholic musings, adding another dimension to the novel – six original pieces of ambient music typified by soothing (occasionally abrasive), cyclical drones and delicately plucked acoustic guitars with a central track – ‘The Deep Hum at the Heart of It All’ – reminiscent of Sonic Boom’s contributions to Spacemen 3’s swansong Recurring (which is a happy coincidence, because ‘Big City’, from that album, was one of the songs Smith listened to as he tramped the streets in search of inspiration). On some tracks Smith narrates extracts from Unreal City in his lulling Hartlepool tones, and the soundtrack and book have been lovingly packaged together with Smith’s text unbound and hilariously annotated by Weatherall (including some brilliant anecdotes about DJ’ing in Soho bars), along with a CD and 10” of the music.

I meet the pair prior to an in-store performance at Rough Trade East on an incongruously boiling hot September evening. We retire to a nearby pub, The Golden Heart, to talk, partly fulfilling my fantasy dinner party daydream. Smith, already nursing a bottle of beer, orders whisky and ginger, while Weatherall, yet to soundcheck and clearly nervous about the debut performance of the soundtrack, sticks to diet coke. As the conversation unfolds, with palpable bonhomie between the collaborators, you get the impression that Weatherall feels like a bit of an imposter in these literary circles. Sitting in meetings under the watchful stare of the T. S. Eliot bust, part of him is still the furniture porter from Windsor. ‘You sit in a room [at Faber’s offices] at a table that once sat T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, with a bust of Eliot looking down at you, and you’re half expecting a voice to go, ‘He’s not wearing any clothes,’’ he chuckles. ‘I feel like the kid who’s forgotten his PE kit.’ But nobody deserves it more than Weatherall. He’d probably hate the “Renaissance Man” tag, but these days he is a man of varied talents – DJ/musician/producer/artist/writer; an eloquent, level-headed bloke who is somehow still sane despite all he’s seen and done. Weatherall has reached out and touched more people in the past two decades than any novelist. In some ways Faber need Weatherall more than he needs them, though that’s rather overstating it. It’s a mutually symbiotic relationship.

On screen some accuse Smith of pretension. Like Jonathan Meades and Paul Morley, Smith is fond of profound verbiage (a trait to be applauded, I think) in place of pithy interpositions, but in the flesh he is charm personified. He’s not on Twitter and doesn’t have a mobile phone, which he obviously enjoys, but he admits that his partner is not so keen on him being permanently incommunicado. However, this eschewing of technology doesn’t make Smith a Luddite – he has strong thoughts on the technological future of the novel that he expands on after our initial interview, in which the pair discuss their collaboration, what London means to them, the pointlessness of nostalgia, gentrification and the glory of wallowing.

How did the collaboration come about?

Andrew Weatherall: It was all the brainchild of Lee Brackstone, the commissioning editor at Faber & Faber. He was bordering on the Machiavellian at times.

Michael Smith: Yeah, everything’s his idea.

AW: I can detect a hint of thickness in your voice there. Was it not his idea?

MS: The way I remember it was, I went to Port Eliot (literary festival) and I had such a magical weekend. It was the first time I’d took ecstasy for a good few years. And the day after I did it, I bumped into him [Weatherall] in a fucking field somewhere and we got chatting.

AW: (laughing) You say we got chatting Michael, but… I’m sitting on a hay bale and you come wandering into view and I know who you are – I’m already a fan of your work – and we get introduced and the basic introductions are out of the way and you utter the lines, ‘I’ve been up for two days, I’m just going for a lie down. If I’m not back in six hours send someone to come and find me.’

MS: See, in my mind I thought I was at my most charming.

AW: You weren’t a sloppy drunk; you didn’t paw my wife’s breasts or kiss me or greet me and pour drink down my back as people have done. I knew you were a seasoned professional so I knew it would be alright to approach you.

MS: I remember thinking, what a lovely bloke.

When you were writing Unreal City were you imagining there would be a soundtrack for it?

MS: Aw no, not really. I wasn’t really imagining it as a book at that point. I was writing little vignettes at the time, but what they’ve added up to… It’s been lovely really. There’s a film aspect to it as well. It’s all just come together. Andrew phrased it beautifully the other day: ‘The alchemy of circumstance’. It seemed to acquire its own momentum.

AW: We’re not careerists, so our jobs just involve all these weird circumstances that happen when you put people together. There’s no board meeting on a Monday with a Power Point presentation or anything, thankfully. When Lee initially approached me and asked if I wanted to do a soundtrack I thought it sounded like a lot of work. I’d done Lee a dark ambient mix with clips of Ian Sinclair and Alan Moore talking over the top, and he really liked it so he suggested we did something similar, but with Michael talking over it instead. We got to the stage where we were having a meeting at Faber and I started glazing over and suddenly thought, ‘Hang on a minute, it’s actually harder work for them to license all these tracks.’ And I turned into the Simpson’s dog, you know, when all he can hear is the voices going, ‘Wa-wa-wa-wa-waaa-wa-waaa’, while I was formulating this idea that I could actually do it myself. The book is only six or seven chapters, so I could do a track a chapter. I already knew how I wanted it to sound and so half way through this meeting about licensing all these records I blurted out that I’d changed my mind and I could do a soundtrack, and once I’d committed it had to be done. It was actually relatively easy. There’s this line in the book – “The deep hum at the heart of it all” – and that was the trigger.

MS: That really runs through the music. It was lovely for me, because originally he’d said he’d do a track and then we’d have a mix CD, but he turned up a couple of weeks later with an albums’ worth. I was over the moon with that.

Listen: ‘The Bells of Shoreditch‘

The music fits perfectly with Michael’s writing – it’s very meditative and cyclical and lulling…

AW: The tone of the book is wistful resignation a lot of the time, and I’m full of wist. [chuckles] I’m 50 now. It’s the most wistful of ages.

How are you imagining people will approach the finished product? Do you think the two (words/music) should be consumed together, or do they need separate spaces?

MS: As a writer I’ve always enjoyed seeing how that would fit with other disciplines. It starts off just as writing but I’ve always found it interesting when you try and combine that with another field.

AW: Personally I would just read the book and then go to the soundtrack to see if the sound in my head was the same. I’d want to come up with my own soundtrack first while I’m reading it and be given as limited an amount of information as possible.

MS: I would hope people would just dip in and out of it. You’d spend quarter of an hour with it and then come back to it. It’s not really written in a linear way. The big challenge was trying to give it a linear structure because it’s so fragmented and episodic. I rarely pick a book up and start at the beginning and get all the way to the end. I’ll read a bit and then go back to it.

AW: That must destroy murder mystery books for you. [laughs]

I received the book late and made the mistake of rushing to finish it before I came to meet you. I was hurtling through it, but of course it’s not like I needed to know what happened at the end!

MS: It wasn’t intended as a narrative arc. They’re more like poems. I was intending for them to be consumed like poems. They’re just little moments really. In the same way you might listen to an album and there’s a track you like and you keep going back to it.

To me it feels like it’s written by somebody who really loves language and words and enjoys putting them together. You don’t get that so much these days, it’s all about driving a narrative from a starting point to the finish.

MS: It’s wax on wax off for me.

AW: Just imagine how good you’d be if you could get that narrative arc?

MS: I know! I’d be a successful writer? [laughs]

AW: Wouldn’t ya? Blimey. [chuckles]

At the start of the book, when you’re on the estuary, there are hardly any full stops. Instead, the sentences are broken up with ellipses. It gives the prose a really nice rhythm, and the words have room to breathe. That device really reflects the surroundings and how you’re interacting with them. But when you come to London the pace picks up and there’s less dot-dot-dots.

MS: I discovered the semi-colon and applied it to the best of my ability when it got to London. [laughs] I love the dot dot dot. I like its inconclusiveness. It’s just a thought in itself – it doesn’t lead anywhere.

It reads like a love letter to London, but it’s also quite cautionary.

MS: It’s a dysfunctional love letter.

AW: In the annotated version, I write at the end, ‘You have just been reading an ‘It’s not you, it’s me’ letter to the city.’

MS: Yeah! That’s well put that. That’s what it is to me as well.

It’s brilliantly observed. A lot of it resonates with me. Did you feel the same Andrew?

AW: Yeah, there’s certain novels that resonate with me because – especially if they’re fin de siècle ones, or late-Victorian ones written about round here, you know, A Child of the Jago and things like that. I walk those streets every day. I’m reading a book at the moment called A Hoxton Childhood and although it’s taking place 100 years ago, it’s taking place right next door to where I live now. Why I connected with Michael’s book is because I’ve been in those places and in those states of disrepair that he has been – probably in the same buildings. [laughs]

Andrew, what are you feelings towards London now, having lived here for the past few decades?

AW: I’ve been here for 25, 30 years. The human condition hasn’t changed for thousands of years. The way cities are and the way we interact and communicate changes, but human beings don’t. So the feelings you have as an 18 year old don’t change, just because All Saints have got a shop on the corner in an area that was once run down. To me it’s a bit annoying…

MS: But if you read De Quincey or Defoe or any of them, they have a similar experience to London as well.

AW: Nostalgia is very debilitating I find, and that’s why I like what Michael does. It’s not rose-tinted spectacles, it’s nicotine-smeared spectacles. I’m the same with music. There’s no point moaning, ‘Oh, the music’s not as good today as it was back then.’ The people who are consuming it now don’t see it that way. Thirty-two years have passed since I was 18. But that 18-year-old person walking round here now, will be feeling the same excitement I was, especially if they’ve come from the suburbs like I did. This was the Land of Oz at the end of the M4. I was in Windsor, it was only 20 miles away, but it might as well have been 2,000 miles away. And as with the Land of Oz, you eventually find out that it’s just some old bloke with levers, but it doesn’t matter. It’s still a parallel universe.

MS: I think when I wrote this book I realised that it was just this old geezer with some fucking levers, man. That was the disillusionment.

AW: But is it disillusionment? Or is it just realisation and awareness?

MS: It’s resignment in a way.

AW: That can be good for you, rather than pretending it isn’t like that.

AW: When you’re a kid and you get into a band and they’re your thing, you want everyone to like them. But as soon as everyone does you’re like, ‘Aw they’re shit.’ It’s that mentality. I think me and Michael are both quite greedy people, in a good way. We’re greedy for experience. I think we’ve both realised that if you sit around moaning about the good old days, what are you experiencing?

MS: Or imagining it was more special when you were there.

It’s like that phrase Andrew uses in his foreword to the book – you’re both looking for “new pastures to turn into battlefields.”

AW: That’s it. I love my heritage and I love what I’ve been through, but to quote Andrew Loog Oldham, “The true hustler always lives for today and tomorrow.” I’m a better person than I was 25 years ago. I’m a better artist, I’m a better writer and I’m glad I’ve had all those experiences but I don’t want to go back or diminish what the next generation are doing.

MS: My friend had a lovely quote about the nostalgic element of the book, which I was really careful to reign in. I’d find myself slipping into it but then I’d edit it out, because I agree – it’s the wrong impulse. But my friend says, “Saying London was better when you turned up 15 years ago is like saying the Alps were better 15 years ago.” They’re the fucking Alps!

AW: But then they haven’t put in retail outlets halfway up the Alps. [laughs]

Is Unreal City anti-gentrification then?

MS: No it’s not. It does make me wistful for another time, but I hope not. I was just trying to observe the process. It’s almost like the overriding social drama of London or my time in London. There’s a line in one of the vignettes that I was really happy with, “London’s central drama was advancing money and the lack of it.” That to me is the central tension of London in a way. There’s this big tide of wealth and then all the people who are in conflict with that. And this area was a great example – it’s on the frontline of that. The Olympics felt like the crowning moment of the gentrification of East London.

AW: But it’ll go in cycles. Two hundred years ago Hoxton was quite fashionable but then it fell out of fashion again.

MS: It’s a dynamic process – there’s bits of West London that look shoddy now. When people find out I live West they’re horrified – it’s like I’ve just insulted their mother or something. But the truth is, now bits of East London are far more chi-chi than West. It moves around. The city is the most complex thing I can imagine. You know how they say that the human brain is the most complicated structure in the universe? Well, imagine eight million of them, communicating with each other? I hope the book is more about the awe and terror of that process.

It paints a romantic picture of being a flâneur; being aimless, having not much money and nothing to do. But it compels you to ditch your job and just meander around and observe. It makes that seem so appealing, not rushing around and having a job and somewhere to be all the time.

MS: But I was only doing that because I had nothing fucking better to do.

But it seems like you enjoyed yourself. Even scoring crack and having a shit time is transformed into an entertaining experience.

MS: It was exquisitely miserable.

AW: The glory of gloom, as Genesis P. Orridge puts it.

You can wallow in the misery.

AW: Believe me I’ve wallowed, but there comes a point when you think, ‘What have I got to lose?’ The reason why I’m not a junkie is because I wallowed until I almost drowned, but then I realised that if I carried on in that way I was going to lose everything. If I carry on this way I may be an interesting character and be able to dine out on the stories, but it gets to the point when I realised that if I could control the psychosis that led me to drink and drugs and channel it towards music and art and writing, I’d be much better off. I can still have those adventures, but I can be an observer rather than somebody who takes part. I’ve got too much to lose. I’m not going to be a millionaire – y’know, I’m 50 years old and I’m still living in rented accommodation – but this system that I’ve set up is conducive to my happiness.

MS: You can’t make money when you’re wallowing.

AW: If you’re wallowing and the bailiff turns up, you can’t go, ‘I shall pay you Thursday, but in the meantime here’s a hilarious theatrical anecdote.’

I suppose for you Michael, your wallowing was channelled into the book.

MS: Yeah, it came out of a time when I was wallowing. For a year or two the arse fell out of everything and I was struggling – money wise and job wise and… There was solace in writing that book in a way. I was in the doldrums. I do worry that the book is negative actually. But I don’t write when I’m happy. I’m too busy getting the rounds in.

It’s more reflective and melancholic than negative.

MS: It was time for me to take stock when I wrote this book. I was accumulating these vignettes and I didn’t know what they were going to be but I knew I had the body of something evolving. There was a funeral I had to go to – one of the barmen I loved in Soho died. And then there was another guy who had fallen out with this bloke and I was thinking, ‘He could have at least turned up for the fucking funeral and made his peace’, but it turned out that he had overdosed that day. So the following week I had another funeral to go to. It was the shock of these two funerals, I think, that gave me the frame for what the subject of this book was. It became about what had been lost, looking at what had passed.

AW: Was it a reminder of your own mortality?

MS: Yeah, I’d look in the mirror and think, ‘You’re getting a bit jowly there, mate.’ I’ve still got the old magic, though eh? But once I’d set myself that framework it naturally became quite a nostalgic thing. And then I realised about a year or two into writing it that I was actually enjoying myself in new ways, I met different people and London was still as much of a mystery to me. I hope I’ve balanced that in the book.

There is no resolution in the book. It’s not like you get a job in the city and that’s the end.

MS: Exactly. I tell you the film that I love… I love Fellini – the end of La Dolce Vita. He’s this paparazzi and he’s sick of his shallow life. There’s this beautiful end scene where they haven’t been to bed all night and it’s the next day and this monstrous fish has washed up in Rome. And they find this fish and it’s horrible and it’s a metaphor for what he does. He catalogues monstrous fishes. Earlier in the film there’s this little girl who’s full of life and hope and youth and she amuses him in this café while he’s typing, and in the last scene they’re on opposite sides of the river and she’s saying, ‘Listen I want to tell you something really good’, but all you can hear is the water and the wind and she’s trying to tell him this thing that’s going to resolve this film, but he can’t hear so he just wanders off. It was the first time I’d not seen a Hollywood ending on a film. It doesn’t resolve it, it affirms the cycle in a way. And it was lovely to know you could do that, because I struggle with endings – especially happy ones. I think the end to my book was just an acceptance – there’s this vast and noble city and we’re just little cogs in it. We come and have our time here and then someone else gets a go.

This is rather a trite question, but are there any of London’s secrets you’d like to divulge?

AW: No, because then they wouldn’t be secrets any more would they? [laughs] I’m trying to think… Just get lost. I’ve lived in London for 30 odd years and I can still take a wrong turn and end up somewhere I don’t know.

MS: A wrong turn’s a right turn.

AW: I was in Clapton yesterday and I’d never seen that view of London before. I was up Clapton Road and I didn’t even know what bit of London I was looking at. Yeah, “Hidden London” is little dark alleyways and all the obvious Jack the Ripper connotations, but the whole of London is hidden, especially if you live in one area for a long time. If somebody hooked me up to a computer they’d realise that I operate within a very limited space. There will still be times I’ll walk down a street and discover a vista I’ve never seen before or see a street name and think, ‘Why the fuck is it called that?’

MS: That’s why it’s so fucking good.

Weatherall goes to soundcheck at this point, leaving me to saunter (that’s how Smith rolls) back to Rough Trade East for the performance (which, incidentally, is fantastic, with Smith swaying like a rock star as he intones a passage from the book with not a word out of place, over Weatherall’s warm synth drones and atmospheric guitars from Nina Walsh and Franck Alba). It is during this walk that Smith explains about the groundbreaking format for the iBook of Unreal City, which incorporates his text and Weatherall’s music with films made by a long-term collaborator of Smith’s, the film-maker Wojciech Duczmal, and makes an interesting footnote to the interview.

MS: Everything’s becoming digital, so the logic is that on an iPad everything is interchangeable. Before you’d have to buy a ticket to the cinema, or buy a book, or get a piece of vinyl – all in separate forms. I don’t see any reason now whey they can’t all coalesce into a total work. The brilliant thing about Unreal City is that there’s going to be an iBook – it’s like an iPad version of the book that has films embedded in it and Andrew’s music. That’s what a book should be now. The films are by this guy Wojciech Duczmal that I’ve been working with. We kept shooting little bits and thinking that we might make a film, but then we realised that to sell a book on an iPad, a little minute vignette of film could do the same job as a passage of text. I’m sure that our children will expect that – all the mediums coming together like this. Text on a page has a quietness and removed sense about it, but people are going to be consuming everything on tablets and phones soon and I was interested to know why you would buy a book on a tablet if it was just words. I’m not precious about words – I’ve done a lot of telly. I just want to create something and communicate something and whatever the medium is kind of dictates the content. So we’ve tried to experiment with that a bit – can it be a film, a book and a piece of music? I think it’s got to go that way really.

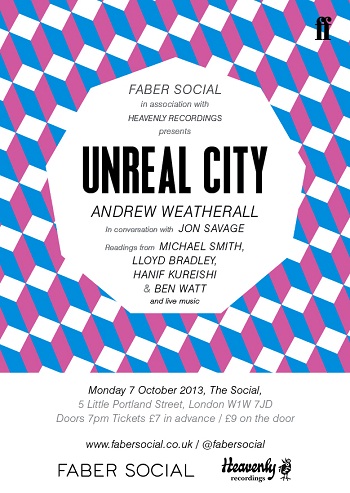

Unreal City by Michael Smith & Andrew Weatherall is published by Faber, £35 Special Edition & as a £7.99 iBooks Author and £7.99 ebook. Andrew Weatherall & Michael Smith will be appearing at Faber Social presents Unreal City on 7 October at The Social