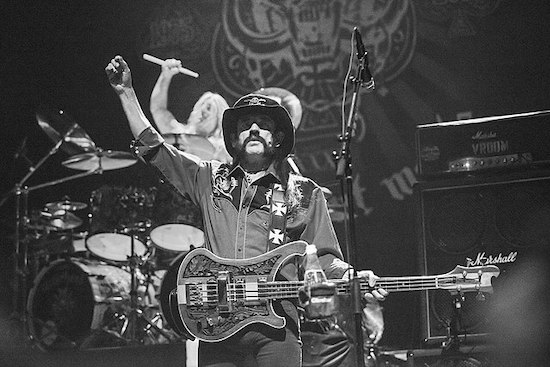

Photo by Jessica Branstetter. CC BY 2.0

The circumstances surrounding Lemmy’s sudden and ill-judged dismissal from Hawkwind heralded the beginning of the end for my involvement with the band. Without Lemmy, Hawkwind was less of a rock ’n’ roll band and I know some of my enthusiasm for the band left with him.

I’d got to know Lemmy pretty well because he used to come in and hang out in the office when Hawkwind weren’t on the road or in the studio. He had this dream of being in the loudest, dirtiest, nastiest rock ’n’ roll band in the world. It was a great calling card, but he hadn’t thought it through. The band wasn’t ready. It was too soon for what he had in mind but I was excited about starting something new with him just as at the point when I was losing Hawkwind. After five years they were out of contract with us by the end of summer 1975.

Lemmy’s first trio came together quickly with Pink Fairies’ guitarist Larry Wallis and drummer Lucas Fox. Doug Smith, who’d managed Hawkwind from the start, was going to manage Lemmy’s new band, and I wanted him around because Lemmy could be a handful. We all agreed on Dave Edmunds producing the band and, having been talked out of calling his trio Bastard, Lemmy decided upon Motorhead. It was the title of the last song he’d recorded with Hawkwind as well as slang for heavy amphetamine use. I’d already put Lemmy in touch with American artist Joe Petagno who’d done artwork for Dr Feelgoods’ Malpractice and Joe came up with the first version of the now familiar skull logo. So it was beginning to fall into place.

They started recording at Rockfield in late September and I went down there after the first week. They’d got four tracks done with Dave Edmunds that sounded great. Dave didn’t look at all well, though. He’d turned green and said: “This is going to kill me. I haven’t slept for five days and can’t keep this up.” Lemmy said later that it wasn’t down to Motorhead’s excessive behaviour or the long hours but because Dave was really stressed out. He’d just done a solo deal with Swan Song – Led Zeppelin’s label – and Peter Grant was pressuring him to get his own stuff together.

We had the studio time booked so I brought in Fritz Fryer. He’d been in the Four Pennies – just about the antithesis of Motorhead – and was now an engineer/producer at Rockfield. It

was a tough ask for him to try and match what Dave had done as closely as possible. Fritz at least finished the tracks, which would have been enough for an album, but while Dave’s tracks still sounded great the rest were more like demos.

We mixed the tracks in January and by then Lemmy was coming in to see me every day wanting this or that because Doug had pulled out. He did return to manage Motorhead again but for the time being the band had no manager. As a result, Lemmy was taking up more and more of my time and we had nothing to show for it. Lemmy hated the album. We couldn’t salvage it in any workable way and he even made me promise I’d never release it. I said, “As long as I’m here it won’t come out.” Next thing he’d brought in a new bass player and drummer in what would become the classic Motorhead line-up with Eddie Clarke on guitar and Phil Taylor on drums. At that point I knew the album we had was definitely a dead duck because two thirds of the recordings weren’t good enough and it was a different band anyway, so even Dave Edmunds’ tracks were now redundant.

I’ve not regretted much. The exception was Motorhead. That was the one that got away. I’d always thought we’d recorded too early and didn’t trust my instincts that the band was under- cooked. I should have given it more time, but the Feelgoods were really happening in 1976 and I felt like I was becoming Lemmy’s stand-in manager so I cut them loose. You can’t lose sleep over things that later became successful. A few years later I was in Los Angeles and I went to the Rainbow Rooms and there at the bar was Lemmy. This was in 1980; Motorhead’s crucial second album for Bronze, Bomber, was out and they’d had a Top 10 EP. United Artists couldn’t resist releasing the ‘original’ first album under the intended title

On Parole. Lemmy saw me and shouted across the bar: “Oi, you bastard – you promised you wouldn’t put that out.”

I shouted back: “I’m not there anymore.”

Motorhead actually started playing dates in July 1975, little over a month after Lemmy left Hawkwind, and usually to pretty indifferent reactions. The only thing they had going for them was that they were loud. I used to wake up the next day after Groundhogs’ gigs with a ringing in my ears but it would fade away during the day. When Motorhead opened for

Blues Oyster Cult at Hammersmith Odeon in October I was standing by the sound desk. It was situated on the ground floor in the centre where the first rows of seats ended. Motorhead

started quietly to a point where people in the crowd were shouting to turn up the volume. Lemmy wasn’t living up to his claims and he was getting some stick. So he kept gesturing to

the soundman to make it louder and louder until at one point I felt a stab of pain in my head and yelped. The damage was done. I’ve had tinnitus ever since.

Happy Trails: Andrew Lauder’s Charmed Life and High Times in the Record Business is Published by White Rabbit Books