Alissa Nutting’s first book was the short story collection Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls. This seems a logical precursor to Tampa, gleefully deemed ‘the sickest, most controversial book of the summer’ by Cosmpolitan: Celeste, Tampa’s protagonist, has a thoroughly wholesome job as a high-school teacher – but her motivations for taking the job are as unclean as they come. Celeste is an extremely good-looking, apparently happily married twenty-six-year-old – with a pathological attraction to just-pubescent boys.

The book was partly inspired by the real-life story of Debra Lafave, a Florida schoolteacher who had a sexual encounter with a fourteen-year-old student. Nutting was struck by the media handling of the case – so different from the approach seen with male sex offenders – which included photos of a bikini-clad Lafave posing on a Harley Davidson and an intimate interview on NBC; it was Lafave’s looks, rather than her crime, that appeared to be the main focus of attention. Tampa seeks to expose the hypocrisy of society’s portrayal of gendered sexuality, where sex for a man is always a prize – therefore an adolescent male who gets it on with an older female is a lucky boy, not a victim – and women are the prize objects.

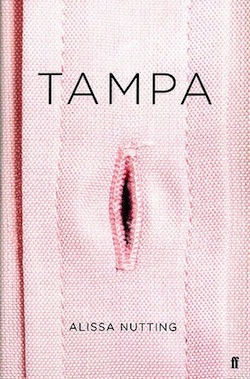

The book’s marketing and reception are ironically (or cleverly?) guilty of some of the same problems that Tampa sets out to satirise. The striking UK book jacket, with its highly suggestive pink buttonhole, calls to mind that dodgy Bill Hicks sequence about the appeal of young girls (‘Because there’s nothing between your legs. It’s like a wisp of cotton candy framing a paper cut’). Consider that this is a book about a female paedophile: in all the decades of Lolita reprints and jacket designs, there has never been one that focused on Humbert’s genitalia. In fact it’s Celeste’s awareness of herself as a sexual object that enables her to ‘sell’ herself to her victims, through the strategic unbuttoning of buttons, among other even less subtle come-ons. Celeste’s power as a sexual predator is her attractive female body – the life span of which she is acutely aware of. As a character she is perhaps more of a metaphor than a figure with true psychological depth (unsurprising in satire) – the monstrous endpoint of a society obsessed with youth, and particularly young women. As one reviewer succinctly put it, ‘Nutting recognises gender for the fucked game it is’.

A book which opens ‘I spent the night before my first day of teaching in an excited loop of hushed masturbation on my side of the mattress’ is wasting no time in setting out its stall, but Nutting seems to be more in the business of exposing than shocking. Like Hicks, she digs deep into taboo to uncover the rottenness within us; Tampa certainly doesn’t make for comfortable reading, but it will raise (at the very least) eyebrows, and a good few questions.

In an interview with Cosmpolitan, you said that the lack of books about female sexual psychopaths was ‘a void in transgressive literature that I wanted to fill’. Why do you feel transgressive literature is important?

Alissa Nutting: I have a core belief that art – all forms of art – cannot belong only to the accepted or redeemed. That is something I am happy to go into battle for. I know that for me personally, time and time again, I seek out art that will disturb me. Afterward, even if I am uncomfortable, upset, afraid, I also feel my perspective of the possible and known has expanded; once again there is more to the world than I’d thought. Good or bad, there is more. I have no other religion but this experience of exposing myself to something beyond the border of what I’d previously encountered, and then feeling the tectonic shift of my own relativity realigning. It’s like my mind takes another breath – sometimes a gasp, sometimes a steady ‘ah’.

You’ve been quoted as saying ‘one of [your] areas of interest is monstrosity’ – could you say a little more about this and what it is precisely about monstrosity and monstrous characters that interest you? Do you have any favourite monstrous characters in literature or other artforms?

AN: I watched a documentary a few months ago called Dirty Work that interviewed a man named Darrell Allen who cleans septic tanks for a living. He gets a kick out of seeing what he can find left behind in peoples’ septic tanks after he’s pumped them out – dentures, coins. He said that the first time he pumped a tank, he got down on his knees and thanked God because he’d found something to do that he was good at. I knew exactly what he meant – I am the Darrell Allen of literature. I’m not like other people; I’m so afraid and terrified of very normal things that freakish and monstrous things don’t terrify or creep me out any worse than I’d already be. It’s been a life-long calling; I’ve always been able to think and talk about things that would depress or abhor others. I’m naturally depressed and abhorred. It’s really no big deal to me. I can write about society’s metaphorical shit. I’m not afraid of the smell. I think it’s hilarious to see what lies buried underneath.

Celeste has been billed as a female Humbert Humbert. Did you set out to write a ‘reverse’ Lolita, or is that just an easy comparison for marketing purposes? Were there any writers or texts that served as models for you when you were writing or that you would consider long-term influences?

AN: It’s a very different book than Lolita, written for very different reasons – and of course written in a very different way, focusing on very different themes. I wanted to write a novel specifically about the phenomenon of female teachers sleeping with underage male students and the social atmosphere, gendered expectations, and fetishization culture in which these cases are proliferating. I’d say my long-term influences are satirists, absurdists, humorists – Kafka, Swift, Sterne, Beckett. I think exaggeration can often be the best way to get a true perspective of things.

Even though Celeste’s victims are boys, it’s the female body that takes centre stage; in her fantasies and when grooming the boys she seems to objectify herself as much as (and sometimes more than) them – do you think female sexuality in today’s society necessarily involves (self-)objectification?

AN: That’s certainly the way that female sexuality is ‘sold’ to us the majority of the time, yes. Celeste is a self-aware object. She objectifies herself in order to get the social benefits that come with doing so, and she passes this objectification on to the young males she pursues.

Celeste is repulsed by older women; she has a horror of ageing and how this will affect her ability to attract boys. In this, she is perhaps as much a victim of society as women leading more blameless lives – do you have any sympathy for her?

AN: We live in a culture where women have less visibility and power as they age, and that’s particularly terrifying for Celeste for a variety of reasons – aging will mean the loss of a great amount of privilege for her. This is one area where even she won’t get a pass. Sure, I can join her in this lament.

These days authors’ personal lives are often drawn into the discussion about their books. One piece on Tampa reassured readers: ‘It’s hard to imagine a character less like its author’ (!). Do you worry that people might be looking for comparisons between you and Celeste and if so how do you deal with this?

AN: It’s just a sad fact. Though authors must have a working imagination in order to write books, a rather sizable number of people believe it’s impossible to apply that imagination to a character’s sexual acts or fantasies – that when it comes to writing sex, suddenly every imaginative skill authors have is voided and they can only write from personal urges. Particularly if the authors are women. Particularly if the authors’ characters are women as well. ‘You wouldn’t be able to think it up if it wasn’t already in your head!’ – people actually believe this, despite the obvious illogic. I’ve written stories about women who date cannibals and women who are sent into space in order to have sex with a winning game show contestant. Let me tell you: I find neither of those scenarios a turn-on.

A number of interviewers have been interested in your family’s reaction to the book, and whether you will allow your daughter to read it. It was also fairly amazing to read in the book’s acknowledgements that you had been pregnant while editing it – as the antithesis of what pregnant women are supposed to be doing, this in itself seemed wonderfully subversive. Do you think people have different expectations of female writers than male ones?

AN: I think that’s true with every profession – I don’t believe I have to deal with more misogyny than women who aren’t writers do. It’s true, though – while my husband was painting the nursery, I was in my office tinkering with paragraphs about illicit sex in between feeling fetal kicks to the ribs.

The book shies away from easy psychological explanations as to why Celeste might have these predilections. Did you actively avoid making ‘excuses’ for Celeste or are you just more interested in exploring the deed than any possible cause?

AN: When these cases come up in real-life, that’s exactly what tends to happen with the media –we look for excuses and reasons why it’s not the woman’s fault. I wasn’t personally interested in a book that addressed ‘why’ – one, it’s a question we’re already asking, and I think our exclusive focus on ‘why’ really negates the abuse that occurred and makes the male student’s victimhood even more invisible. Two, I think ‘why’ is likely a pretty diverse spectrum. I didn’t want to write a novel that aided in the simplification of this phenomenon, or seemed to be making a universal psychological diagnosis. My novel is a book about the social factors that cause this behavior to be seen as less of a crime when it’s a female perpetrator and a male victim, and the social factors that might excuse extremely destructive behavior by a woman based upon how she looks.

Celeste’s sexuality is so palpable that some aspects of the book are uncomfortably erotic, something that becomes increasingly disturbing as her transgressions escalate, making the reader almost feel implicated in her actions – does the possibility that a real-life sexual predator might find the book a turn-on concern you?

AN: No. I’m sure that when real-life sexual predators want to get turned on, they have far more effective materials than my book to turn to – texts that don’t portray them as narcissistic, remorseless monsters; texts that have illustrations; texts that don’t waste their time with pesky literary devices like situational irony.

The frankness of your descriptions of female sexual arousal is refreshing, and in a way it seemed a shame that they were appearing in a book about a sexual predator – the danger being that in a society in which women’s sexuality is still subject to various taboos it might reinforce a sense that a highly sexed woman is necessarily an aberrant one. Was this something you considered?

AN: Those gender taboos are a very important part of this novel. Our social inability to see women as sexually predatory toward men is very much linked to not being able to view female sexuality as prolific or powerful in general – linked to the fact that ‘normal’ sexuality for women is commonly regarded as being a watered-down version of male sexuality. If Celeste were some externalized sex-witch who a far more mainstream female protagonist was battling with and overcoming, or marginalizing by comparison, then yes, I think the novel would reinforce that gender myth. But Celeste is a first-person protagonist, and a self-aware one who uses those same gender myths to her own advantage. The joke’s not on her. It’s on everyone else.

Tampa is out now, published by Faber & Faber