The other ‘Stairway to Heaven’ was composed by Allan Gray, for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1946 film A Matter of Life and Death. It consists of a short, slightly dissonant, uneasy piano phrase, repeating before being accompanied by sparse, equally queasy strings; the sound of being somewhere between, the sound of stasis, suspension and uncertainty. In the film, it starts up in those moments where our hero – who should be dead – travels between the existing world and a heaven that may only exist in his head. A Matter of Life and Death is often, like most Powell and Pressburger films, described as being extremely English, in its manners, in its gentle surrealism, and in its politics, summed up by fighter pilot David Niven’s yelled credo, as he seems to be falling to his death: ‘Conservative by nature, Labour by experience!’. But its co-director, co-producer and writer, Pressburger, was a Central European Jew, Hungarian-born, Romanian-raised, who made his name in the film industry of the Weimar Republic, working as a screenwriter at UFA in the early 1930s. The fantastic cosmic-bauhaus sets are also courtesy of a German, the designer Alfred Junge; the outfits, in heaven and on earth, are by the painter Hein Heckroth; Gray’s music is conducted by another German émigré, Walter Goehr. This is an extremely Central European England.

Missing Musicians

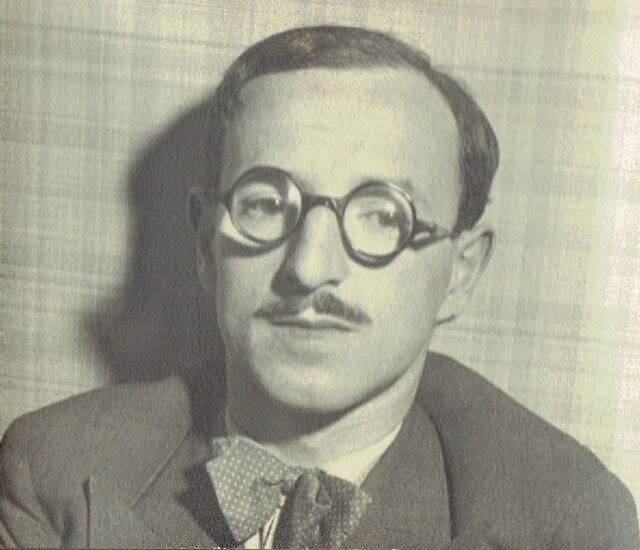

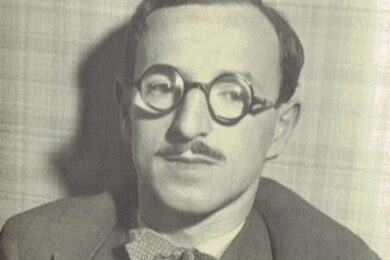

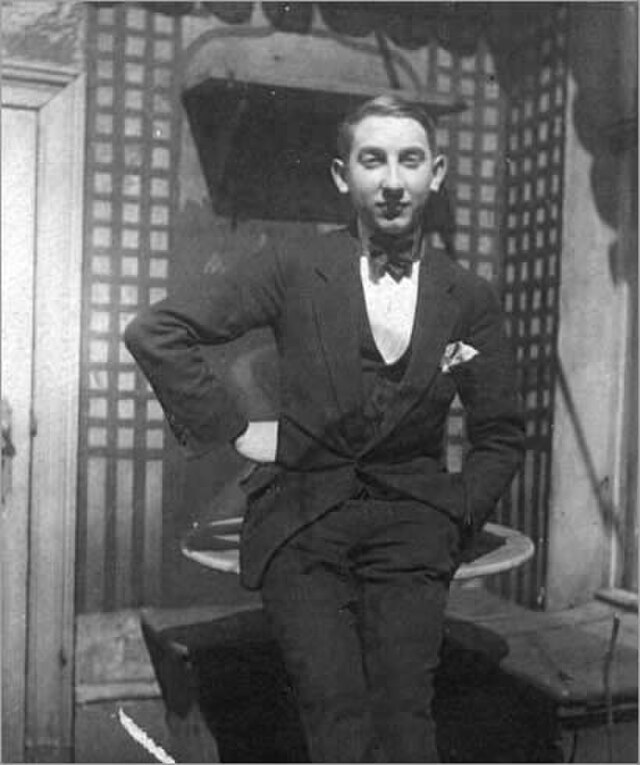

Allan Gray himself is the only musician discussed at length in my book, The Alienation Effect, an account of the art and ideas of those Central European intellectuals who had been forced by the rise of fascism in continental Europe to take refuge on the island of Great Britain. Gray was born Józef Żmigrod, in the part of southwestern Poland then occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and was educated in Berlin; in the 1920s he moved to Vienna, to study with Arnold Schoenberg, before becoming a film composer. Among his early works is the alternately punchy and quizzical score for the 1931 adaptation of Emil and the Detectives, for which Pressburger wrote the script. A figure like Gray linked the commercial world of cinema and the avantgarde represented by Schoenberg, connecting traditionalist Englishness to the urban, urbane modernism of Weimar Berlin – which is, in short, the tale that I try to tell in the book. Mostly, however, I left musicians out of The Alienation Effect, an omission I’ll try to explain and rectify below.

The emigration of artists and intellectuals from Nazi Germany and its takeover of Europe is usually told as an American story, in which Mondrian accidentally gives the CIA an idea of how to market modern art, Schoenberg moves to L.A and accidentally invents horror film music, and Gropius goes to Harvard and accidentally turns modern architecture into a boutique style for rich people. The Alienation Effect concedes that the USA was indeed much more appealing for most, and I firmly endorse the once-conventional wisdom that British culture in the 1920s and early 1930s, was, with occasional exceptions, defined by a parochial, frightened, small-minded conservatism, especially in fine art, photography, cinema and architecture, which are accordingly the book’s main subjects. It tells of how a much more radical culture arrived here by geopolitical happenstance, from Berlin, Vienna, Prague, Budapest and Warsaw, and in the process, art ideologies such as Constructivism or Expressionism were either domesticated and Anglicised, or communicated to their new home in all their full force. Music actually fits very neatly in this, insofar as British composers of the interwar years thoroughly sat out the innovations taking place in Central Europe – whether the atonality and subsequently, serialism of the Second Viennese School, or the Bauhaus-aligned, firmly utilitarian Gebrauchsmusik of Paul Hindemith, or the experiments with fusing European modernism and jazz being made by Kurt Weill or Ernst Krenek. What complicates this, though, is the spectacular success of, especially, German and Viennese musicians in Britain from the forties onwards.

In fact, much of the British classical music establishment is an émigré product – in terms of its institutions and festivals, in particular. During the course of the 1940s, the Glyndebourne Opera was founded by the German conductors Fritz Busch and Hans Oppenheim, with the Austrian producer Rudolf Bing; Bing would then set up the first Edinburgh Festival, along with the Austrian composer Hans Gal; while the Covent Garden opera company was largely built up by the Austrian composer and conductor Karl Rankl. They were able to successfully introduce English and Scottish middle class audiences to much European music of the late 19th and early 20th century, but the more abstract modernism of the Second Viennese School was not part of the repertoire of any of these institutions. Many more Central Europeans would become programmers and musicians at the BBC, and would be similarly careful to educate without frightening their new listeners. Those who stuck to a hard line would have a tough time. The composer Leopold Spinner, a major figure of Second Viennese School, became a lathe operator in Bradford and was then gainfully employed at the music publisher Boosey and Hawkes as an editor. The experimental radio producer Ernst Schoen, a Marxist and a close friend and collaborator of Walter Benjamin, hoped to rebuild something like the Weimar avantgarde in London, but ended up with little more than a discussion group in Surrey with a few actors, architects and writers, closely monitored by MI5 (a story recently told in Sam Dolbear and Esther Leslie’s book Dissonant Waves).

When pop music and its outgrowths emerged in the sixties, all of this was a little bit of a joke. In 1967, the German musicologist and BBC radio presenter Hans Keller interviewed Syd Barrett and Roger Waters of The Pink Floyd, and while obviously intrigued by their ‘regression to childhood’, famously asked ‘why does it happen to be all so terribly loud?’ You can find an emigre presence in pop if you look hard enough. Many of the best early Beatles photographs were taken by the Slovak émigré Dezo Hoffman; the lead violinist on the orchestral arrangements in Sgt. Pepper was an Austrian émigré, Erich Gruenberg; and the arranger Angela Morley, who would create the epic backdrops of Scott Walker and Dusty Springfield’s sixties records, learned her trade at the shoulder of the conductor Walter Goehr. But mostly, these worlds are very distant, perhaps especially because the avantgarde many emigres had emerged from – Schoenberg, the twelve-tone system and the various forms of self-limiting, almost mathematical serialism that were developed to supplant traditional tonality – had almost zero influence on popular music; they usually required far too much in the way of musicological education and technical proficiency to have much appeal for usually self-taught rock musicians. But what did happen was interesting enough in its own right.

Early English

Some of the music of these emigres has been rediscovered in the twentieth century, and added to the repertoire of European art music. One example here is the work of the German composer Berthold Goldschmidt, who had worked with Ferruccio Busoni and with Schoenberg before being forced to flee Germany in 1935. Goldschmidt was one of many experimental composers whose work was labelled Entartete Musik, ‘degenerate music’, which went alongside ‘degenerate art’ like Expressionism, Constructivism and Dadaism. A touring show was set up by the Nazis to ridicule this allegedly ‘Judeo-Bolshevik’ music (many of these composers were Jewish, and a handful were indeed Bolsheviks, but all of them would have considered it absurd to claim atonality was specifically Jewish or socialist). The work of Goldschmidt’s that has received most attention is the opera Beatrice Cenci, with a libretto by the Hungarian critic Martin Esslin, based on a poem by Shelley; it was composed for the 1951 Festival of Britain on the South Bank of the Thames, an orgy of ‘Englishness’ which was substantially executed by émigré artists and architects. It’s a powerful work, and it stays tonal and relatively palatable to delicate English ears, modernist without being avantgarde. A planned ‘opera contest’ at the Festival – for which Goldschmidt had already received the award for the best opera – was never actually held. Beatrice Cenci was first performed in 1994, two years before Goldschmidt’s death.

A similar search for English subjects for new music was taken by the composer Egon Wellesz, another pupil of Schoenberg, who went from a Vienna adaptation of The Bacchae to setting the poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins in 1944. Much of this music, often moving in its troubled nostalgia, can be found on the Ensemble Modern’s tribute to the Central European emigres of London and Edinburgh and Cardiff, Continental Britons, recorded at the Wigmore Hall in 2002. Within this vein of work, one can construct an alternative twentieth century in which Britain was wholly part of the mainstream of modern composition rather than, as it largely was in fact, something of a backwater, at least until the seventies. The music of Goldschmidt or Wellesz sounds logical alongside that of much younger modernist composers from an émigré background, such as the Berlin-born and London-raised Alexander Goehr, son of Walter, who worked for decades in a hard-edged, strongly European manner; or the recently rediscovered Erika Fox, born in Vienna in 1936 and still with us. Fox’s compositions, which combine the abstraction of the Second Viennese School with melodies taken from Hasidic tradition, were recently collected in the album Paths. Both Goehr and Fox’s work paid explicit tribute to the annihilated world of Jewish Central and Eastern Europe, which survived in fragments and memories in London in the decades after the war.

A German composer attempting to create a modernised ‘Englishness’ for frankly ideological reasons was the committed Communist Ernst Hermann Meyer. A pupil and collaborator of Brecht’s favoured composer Hanns Eisler, Meyer was committed to combining his politics and his music – he taught music for the Workers Educational Association and for socialist groups, and worked on an influential study of Early English Chamber Music. Like Eisler and Brecht, Meyer regarded the world of conventional European classical music as intrinsically bourgeois, and reached into the pre-capitalist past to find a sophisticated ‘people’s music’ as an alternative. Meyer earned a living for a time composing soundtracks for the Anglo-Hungarian animators John Halas and Joy Batchelor, with cute essays in Gebrauchsmusik adorning industrial shorts such as Facts and Figures, Friction and Loss of Pressure and The Making of a Jet. Ironically, Halas and Batchelor would become best known for a CIA-funded feature film of Animal Farm, with music by another émigré, the Hungarian Matyas Seiber. By the time that film was released, Meyer had escaped the increasingly McCarthyite climate in London, to East Berlin. He kept in touch with Britain, and with those like the socialist modernist Alan Bush who were trying to bring together modern music and leftwing politics. My second-hand copy of Meyer’s Shostakovich-like Symphonie fur Streicher is inscribed by the composer, presumably to his animator colleagues: ‘John and Joy with kindest regards, from Ernst (of old). Berlin, February 1970’.

To British listeners in the 1930s, ‘Vienna’ didn’t necessarily mean Schoenberg’s experiments in tonality, Alban Berg’s excoriating operas about sex work or Webern’s deconstructed piano etudes. It meant Strauss, and it meant waltzes, the music of an elegant aristocracy and the only-recently deposed Hapsburg court. Accordingly, many composers who had a vanguard past would find themselves earning a living in the world of ‘light music’. In 1940, the Czech composer Vilem Tausky, then in the Czechoslovak army, would witness the firebombing of Coventry from nearby Leamington Spa, and worked clearing the wreckage and treating the victims; in 1941, his moving, unsentimental ‘Coventry Meditation’ surveyed the damage. Tausky was the music director for the Welsh National Orchestra in Cardiff for a time, but he paid the rent by conducting the BBC’s decidedly light programme Friday Night is Music Night. Probably the most interesting figure spanning the avantgarde and kitsch was the composer Wilhelm Grosz. In Weimar Berlin, Grosz had made his name with the fascinating Afrika-Songs, a series of settings of poems by Langston Hughes, which have some of the sour vigour and jazzy swing of Kurt Weill’s work at the time with Brecht, like Mahoganny or Happy End. In Britain, Grosz composed pop tunes under the name ‘Hugh Williams’, and some were genuine hits – the longing and irony of his ‘Harbour Lights’ would fit perfectly on the soundtrack to Pennies from Heaven, and when recorded by the Matrix Ensemble for the ‘Entartete Musik’ series of records of music banned by Nazi Germany, the song reappears as a long-lost, bittersweet Kurt Weill Broadway number.

Matyas Seiber, who moved from his native Budapest to Frankfurt in the 1920s, was an early adopter and lecturer on jazz, which did not endear him to a regime that considered jazz to be inherently inimical to the Aryan race. In his British emigration, Seiber continued to compose, with some very peculiar subjects – cantatas based on both James Joyce and William McGonagall – and like Grosz, wrote a few pop hits under pseudonyms. Grosz and Sieber’s interest in jazz was common to many Weimar modernists, and could be both an example of exoticism and an attempt at an antiracist politics, and an expression of anti-colonialism, sometimes all at once. A figure who sometimes moved in this grey area was the Polish-born, German-educated Mischa Spoliansky, a songwriter who ran revues in Weimar Berlin, in the course of which he ‘discovered’ Marlene Dietrich, a lifelong friend. Spoliansky composed arguably the first explicit ‘gay anthem’ of the twentieth century, ‘The Lavender Song’, which was written for the German sexologist and socialist Magnus Hirschfeld. In emigration in Britain, Spoliansky worked for the Hungarian émigré team of Alexander, Zoltan and Vincent Korda on the Nigeria-set Sanders of the River, in close collaboration with its star, Paul Robeson. The songs Spoliansky and Robeson put together for the film were faked versions of ‘African music’, deliberately inauthentic experiments in pseudo-ethnography. There were limits to how far such alliances could go – the film was mutilated in the editing to present a much more fawning account of colonialism, leading to Robeson disowning it. A more serious project was made by the emigre musicologist Klaus Wachsmann, who after the war would move to Uganda – then still a British colony – in order to research and record traditional music in the region. In these experiments are perhaps anticipations of something that could meld together European modernism and the equally experimental, but decidedly less bourgeois world of African-American music, something which wouldn’t emerge until decades later.

Bargain Bins

But there is also a lot of kitsch – a German word, after all. Second hand bins all over Britain are full of records by Ray Martin and His Orchestra, themed LPs such as Music for Romance, Music in the Ray Martin Manner, or Up, Up and Away, the Bright and Bouncy Sound of Ray Martin, his Orchestra and Chorus. This gloop was the work of Kurt Kohn, a bandleader who had studied at the Imperial Academy of Music in Vienna, before escaping to Britain; at the start of the war Kohn, like hundreds of other German and Austrian refugees, was deported to Australia on the notorious ship the Dunera, whose British officers beat and starved the passengers (this caused a scandal which led to the gradual ending of the previous policy of interning even anti-Nazi and Jewish refugees). After these horrific experiences, Kohn renamed himself Ray Martin, and did very well serving up horrible dross to ignorant Brits: those who appreciate the naffest kitsch might find something to enjoy in Ray Martin’s The Sound of Sight, an experiment in charity shop synaesthesia. Another figure wilfully crossing the border of classy and kitsch was the composer Joseph Horovitz, who was son of the founder and publisher of the Viennese art publishers Phaidon, Bela Horovitz. Joseph, who was only 12 when he emigrated, became known for the ‘pop cantata’ Captain Noah and His Floating Zoo, and later composed the music for Rumpole of the Bailey.

British cinema was a conduit for much avant-gardism and much kitsch. One very famous Hollywood composer, Miklos Rosza, was first lured westwards from Budapest by the Korda brothers, to their studios in Denham outside London, where he worked on their stupendous and dubious epic The Thief of Bagdad. Beneath him are dozens of lesser-known names, like Fritz Spiegl, who wrote the theme for Z-Cars and the jingle for BBC Radio 4. Allan Gray, meanwhile, wilfully flitted between art and commerce in his soundtracks for Powell and Pressburger; while his teacher Schoenberg would have been horrified by much of his work for the duo – conventional, swelling, romantic – there is also a strong, hard-edged expressionism at work too, especially in Gray’s music for the surrealist Scottish Highlands dreamworld of I Know Where I’m Going! (Gray was one of many composers to realise the usefulness of atonality in soundtracking scenes where characters are nearly drowned in whirlpools). One of Gray’s contemporaries in the film world of Weimar Berlin was Hans May, who happily soundtracked both vanguard films such as Battleship Potemkin or Pabst’s Ilya Ehrenberg adaptation The Love of Jeanne Ney, along with much forgotten schlock with titles like I Lost My Heart in Heidelberg and Only a Viennese Woman Kisses Like That. In Britain, May would compose the music for dozens of films, though perhaps only his work on the Boulting Brothers’ Brighton Rock really stands out.

Film also lent itself to parody and exercises in stylistic pastiche, an interest shared by many émigré composers – the BBC ‘humourist’ and Berliner Gerard Hoffnung hosted an annual festival of musical comedy during the 1950s. Among its successes was a version of ‘The Lambeth Walk’ in the style of various classical composers, written by the Nuremburg-born composer Franz Reizenstein, a student of Hindemith. Reizenstein is known among enthusiasts for European twentieth century music for his cantatas, quintets and operas developing the ideas of his teacher, and among enthusiasts for schlock cinema for his high drama scores for Hammer, such as The Mummy, Circus of Horrors and The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb. Similarly, Francis Chagrin – born Alexander Paucker in Bucharest – is important in the history of modernist music in Britain for co-founding the Society for the Promotion of New Music, which tirelessly lobbied for the avantgarde in an initially hostile environment, but he earned money scoring The Colditz Story and The Daleks’ Invasion of Earth.

Mostly, these scores are quite traditional – the emigres were hired not because of their modernist training with Hindemith or Schoenberg, but because they were competent composers and conductors in a country which didn’t have too many of either. For a film where the music is taken seriously, not as a spur to emotion or horror but as a non-diegetic part of a fully thought-out work, you have to wait until the British New Wave of the turn of the sixties: specifically, Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life. Its score was sparse, minimal, astringent, unshowy, never telling the audience what to think or feel, but perfectly of a piece with its monochromatic, emotionally repressed and violent image of the north of England. It was written by another student of Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard, born in Catalonia to a German family, but trained as a composer in Vienna. Gerhard was a supporter of the Spanish Republic, and fled Barcelona to London when it lost the Civil War with Franco’s German-backed fascists (as a Spanish citizen, Gerhard was not, unlike many of his German, Austrian and Hungarian contemporaries, interned during the war). In the 1950s, Gerhard was among those who were not content to meet the English listener where they already were and to nudge them gently towards art: this made him perfect for a critic and director like Anderson, who considered much British film up before the sixties to have been patronising, ingratiating and middlebrow.

Electronic Emigres

Gerhard is, along with another figure, the German choreographer and producer Ernest Berk, the émigré musician whose work might sound most ‘contemporary’ to the ears of a Quietus reader – the work of both can be electronic, playful, rhythmic, and sometimes rather psychedelic. Gerhard is the better known of the two, still largely as a classical composer, but he has also been claimed as the first electronic composer in Britain, due to his incidental music for a 1955 RSC production of King Lear. Gerhard’s electronic music was recently compiled by Alex Harker at the Centre for Research in New Music at the University of Huddersfield, on the revelatory album Electronic Explorations from His Studio and the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. As the title suggests, Gerhard worked at the famed Maida Vale studio, one of only two outside composers who were given permission to work with its various improvised electronic machines and instruments; in 1965, he would work directly with Delia Derbyshire on his orchestral drama The Anger of Achilles. There are wonderful photographs from the time of the already elderly composer standing calmly with his hands over the tape machines at his home studio in Cambridge, as if they’re decks.

The recently rediscovered electronic pieces of Gerhard are densely atmospheric, full of manipulated acoustic sounds rather than pure electronics (Gerhard proclaimed himself ‘allergic to sine waves’, and contracted out the white noise on one piece to the Radiophonic Workshop). ‘Audiomobiles (in the Manner of Goya’), for instance, consists entirely of piano, albeit stretched, distorted and rendered barely recognisable in the studio; the stunning ‘Audiomobiles III: Sculpture’ is a recording of the sounds produced by a metal sculpture by the artist John Youngman, anticipating German music of the 1970s and 1980s in its chiming and bashing – the early Neubauten if they were sixty-something old men living in Cambridge. The great find, though, is the 1959 ‘Lament for the Death of a Bullfighter’, a setting of a poem by Lorca, who Gerhard had known during the Spanish Republic; it is an exceptionally intense, moving work of spoken word fused indivisibly with electronic music, at least on the level of Delia Derbyshire’s Inventions for Radio.

When I first came across Ernest Berk, I assumed he was somebody’s Ursula Bogner style joke. An anti-Nazi exile turned fearless electronic pioneer, who had been a dancer in the Weimar Republic and worked both with Max Reinhardt and with Peter Zinovieff? Who nobody had ever heard of? I smelled a rat, but was wrong: Berk was very real. He was one of many dancers who fled Nazism and ended up at Dartington Hall, a school founded by wealthy hobbyists in Devon which has been slightly fancifully described as the ‘English Bauhaus’; he danced and choreographed at Glyndebourne and Covent Garden, and in the 1950s, became interested in the electronic music that was emerging out of his native Cologne. Berk gradually built a studio in Camden where he would be able to compose music for his own ballets: the results started to trickle out into the retroculture of the 21st century when Trunk released Electronic Music for Two Ballets, a highly percussive, aggressive experiment made in 1970.

Berk composed dozens of electronic pieces between 1957 and 1980, before abandoning his studio and returning to Germany, this time to Berlin; his archives, held in Cologne, were thought lost after a building collapse in 2009, but what survives has been digitised and is being gradually released. What is striking listening to Berk’s music is that compared to most of his contemporaries, it sounds so much more like electronic music as we now understand it. Although it’s frequently atonal, there is melody, sometimes almost jingle-like in the manner of the Radiophonic Workshop, and there is rhythm, lots of it – after all, this is music for dancing; the lazy description of something being ‘proto-techno’ is very easily applied to Electronic Music for Two Ballets. But a more complex picture is revealed in last year’s career-spanning double album Diversed Tapes, another impressive archival achievement from the University of Huddersfield’s researchers into lost experimental music. Something like the 1957 ‘End of the World’ is utterly forbidding, all explosions of bleak sound, ticking clocks and marching footsteps, heavy with Cold War dread; but work like ‘Group Dance’, of 1966, has a sense of cosmic possibility, electronic music as a microcosm of utopia. But what one most notices in Diversed Tapes is something quite new: volume. Berk’s pieces are full of attack, clattering percussion, thick atmospheres and sudden stabs. Hans Keller might have been horrified to find that one of his Central European contemporaries was capable of being loud, louder even than The Pink Floyd.

The Alienation Effect by Owen Hatherley is published by Allen Lane