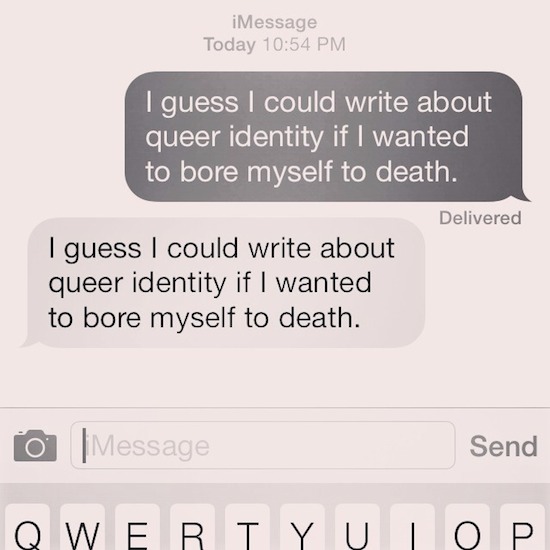

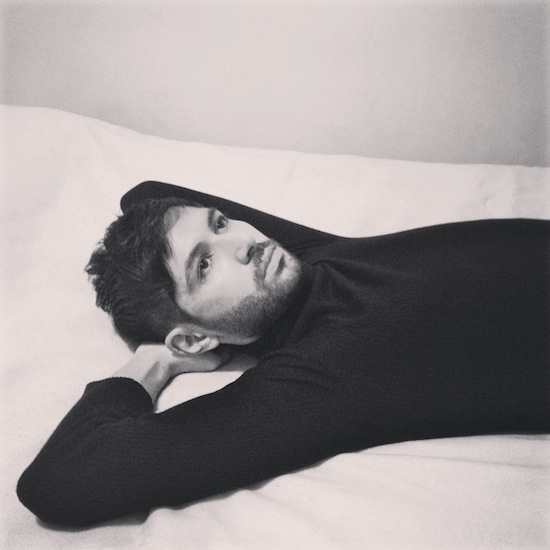

The first time I saw Alex Dimitrov was on Instagram – he was handsome and sullen, preferring to flip the viewer off rather than smile. He had a beard. He dressed in black. His photographs were nonchalant but poised and showed him often enjoying New York by night or in the very early morning. But he also wrote poetry and peppered his Instagram feed with screenshots of text conversations like, ‘I guess I could write about queer identity if I wanted to bore myself to death’. I was intrigued, well perhaps more than that – I was digitally besotted, so I started to follow him.

After a few weeks of stalking Dimitrov on Instagram, his debut poetry collection Begging For It arrived in the post. I immediately found his poetry to be utterly open and frank, containing these small sexual vignettes that demanded to be read, absorbed and then passed over as if they might simply be the stuff of every day life, ‘In bed, a man once asked/ to be blindfolded while another choked me’. Then, after delivering their initial punch, Dimitrov’s compelling poetic narratives gave way to authentic ruminations on poetic form or bleak closing statements that left the reader, me, completely isolated and bereft. ‘Don’t worry. No one is spared’.

My favourite poems in Dimitrov’s book dealt with his father – indeed his poem ‘The Crucifix’ defies rudimentary description here suffice to say it is perhaps the most disquietingly erotic poem I have read in many years – and his best poems also dealt with this seemingly crushing sense of loneliness felt by the habitual city dweller – the way in which I have come to know Dimitrov from glimpsing his dreich black and white photos of a faded New York. Indeed paeans to his city often ended in utter sadness, ‘he feels himself tired and tremendously alone’.

Dimitrov writes firmly in the tradition of James L. White’s seminal book, The Salt Ecstasies, wanting also to poeticise the details of a gay man’s life as much as make them usual and everyday. Dimitrov does this in part to educate the reader, impressing upon them that queer verse is just verse, but also in part to challenge and shake them. Dimitrov also borrows some of Whitman’s rhapsody when he writes of past New Yorkers or lost gay men roaming New York for love, but he can be even darker, ‘When he unbuttons your shirt/ he is teaching you kindness/ and ruin he learned from his father’. In fact Dimitrov is something of a melting pot of other queer poets, utilising Doty’s colours, O’Hara’s pith and Gunn’s solitude; obviously an avid reader, Dimitrov has consumed his influences to produce vivid and passionate verse that at times masquerades as fashionable emotional emptiness, ‘Let’s talk about language while people die’, but is in fact deeply rinsed in a passion for language, humanity and the erotic.

But Dimitrov is not just a writer, he is something of a poetic force of nature. His queer poetry salon Wilde Boys, which attracted such guests and readers as Mark Doty, Marie Howe and John Ashbery, garnered much international attention – with poets everywhere wondering if the halcyon days of the literary salon might return – it was even glowingly written about in the New York Times. And his recent project Night Call, saw Dimitrov traipse around his beloved New York and indeed the world, via Skype, to give private and intimate readings of his own poetry to fans in their own bedroom. In fact interest for Night Call was so overwhelming that my request to have a Skype reading from Dimitrov for me, my boyfriend and my cat was sadly refused.

Hours after sending my formal request for an interview, I received Dimitrov’s response – ‘How shall we start?’ I was thrilled and so began many weeks of emailing back and forth questions and answers that were often accompanied by seemingly off the cuff observations about his city and the changeable and emotive weather; even in his emails Dimitrov revealed his intense passion for language. One email even contained some observations about a poem of my own that he had found online, he wrote, ‘Is this you?’ before proceeding to quote myself back to me. That made my week/ month, I am not embarrassed to say.

Throughout the course of my correspondence with him, I found Dimitrov to be open, honest and above all else considered – he would often email me corrections of his own answers and indeed soon took to reediting himself. I have lost count of how many new versions he sent me of his answers; Dimitrov is clearly a man who prides himself on being accurate, concise and also deeply cares about the image he projects to the world and his readers – and although I promised to publish his final editings of his own answers, I of course chose what I considered to be his best answers, his most revealing; an overzealous interviewers’ prerogative, you might say.

When did you start writing and in what form? Can you remember the first thing you ever wrote?

Alex Dimitrov: The first things I remember writing, when I was six or seven years old, are things I thought of as autobiographies. They were written in the third person, strangely. I’d start one almost every other week and abandon them just as frequently. This came from my obsession with chronicling everything that happened to me, and it’s quite humorous to me now, looking back, that I thought I had a story to tell at six years old. But of course I did. Half of having a story to tell is imagining that you have a story to tell. Imagining a life for yourself, some kind of reality not found in reality.

Should a reader be looking for ‘you,’ for autobiography, in your poetry?

AD: I actually don’t think this question is as important as it’s made out to be but I think it’s important to answer it. I’m interested in connecting with readers and strangers through poetry. I want to create real intimacy with my poems. Whether I do that through pulling from my personal life or using my fantasy life—or say history, whether that history is personal history or our collective histories—what’s important is that an experience is created. An experience that will hopefully matter to people and feel real. I want my poems to move people and make them want to live their lives, however complicated and impossible those lives may be. I think a poem can speak to the life you currently live but also to the lives you’ve lived before, the ones to come and also those you’ve yet to imagine. What else can do that? Not sex or money or other people.

Is your project, Night Call, a way of further creating intimacy between you and a reader?

AD: Yes. I wanted to use social media and the internet (that anonymous and highly [im]personal space), to quite literally be in bed with my readers, reading them new poems. I posted a letter in which I describe the project on my Tumblr and set up a gmail account, makeanightcall@gmail.com, and people wrote me…asking me to come to their bedrooms (if they lived in New York) and read them poetry. If they didn’t live in New York I just put my Mac on my bed and turned on the camera and there they were. All the poems I read during Night Call will be in my second book, which I’m writing now. I’ve almost forgotten about the first book, I love this new one so much. I’m spending some time in Los Angeles this summer to work on it.

That first book, Begging for It, at times seems like the extended interior monologue of an openly gay man, who is as engaged with life, and experience – not just sex. Is it important for you to write queer poems that aren’t just about sex?

AD: I don’t think I write queer poems. If people think I do, that’s fine. It’s not important to me to write any kind of poem specifically, other than the one that most brutally and honestly describes what it feels like to be a living person on earth right now. I’ve written very few poems about sex actually. Probably more love poems than sex poems but that’s not even accurate since what even is a love poem? Somebody leaving? Meeting someone? Spending your life with someone? Spending a day with someone? I want to write about all of those things. Being a man, and being a gay man, those things aren’t important to me as a poet. Perhaps they used to be, but to be honest, I’ve never trusted identity or what it had to tell me. Like I mentioned earlier, those adjectives (gay and male) may be important to other people when they read me, or perhaps some readers come to my work because of them, but I have no control over that. A lot of women write to me about my poems. And during Night Call quite a number of the participants were women. I didn’t think anything of it but I’m mentioning it here due to the context.

I think earlier in my writing life I had an interest in what being a “queer” poet meant, maybe when I was starting Wilde Boys, my poetry salon in New York, but I grew bored with that question quickly. And just like the salons became more about life and poetics at large…I guess what I’m trying to say is—I have nothing to say about queer identity consciously in my work. I want to know why we’re here or why there’s anything at all. Why some days I’m sad walking down the street with nothing to be sad about and why some days I’m happy walking down the same street. I mean, don’t you want to know that too?

I’m curious to ask about the role of the father in Begging for It, he seems always asleep or absent, represented by his crucifix or his underwear.

AD: The father is prominent in the book’s first section, the childhood poems. So are God and early lovers and many other male figures…though I should say I don’t think of God as having a male energy. In those poems God certainly does. But I’ve changed my mind. I’ve changed my mind about a lot of things. Maybe even fathers. Like Willem de Kooning said, “You have to change to stay the same.”

How do you view social media, like Twitter and Instagram, and is it important for you to have an online presence through them?

AD: I treat social media as an art form. Like choosing what clothes you’re going to wear or how you walk down the street or the way in which you interact with people. All of these things are part of the art of living. I see almost every aspect of my life as being in conversation with art. Social media fits in with this way of thinking quite seamlessly. I’m actually teaching a creative writing workshop at Bennington College this fall called “Reading and Writing Poetry in the Age of Social Media.” I can’t wait. I think the poets growing up with social media are going to change poetry more than any other poets before.

Who contacts you through social media? Fans? Men? (And do you always respond?)

AD: A lot of people interested in my work, yeah, and sometimes people interested in me, sure. I try to respond to everybody. I mean, one reason I wanted to do Night Call was because as my book came out last spring, someone tweeted at me asking what it would take for me to read to them in bed because I wasn’t doing readings anywhere near them. Night Call kind of marries your question—interested in the work, interested in me. I think that part of my work makes certain people very uncomfortable. But that’s okay. I’m not here to make people feel comfortable.

In interviewing Dimitrov, I wanted to uncover the actual man behind the social media-savvy poet who has knowingly turned projecting his life to his fans and readers into something of an art form. I am sure this sounds terribly naïve, perhaps even as naïve as asking a twenty first century gay poet if he considers himself to write queer poetry, but that’s the truth. I wanted what all readers want from poetry, after the hit of pure verse – to glimpse the autobiography that might be tucked between each carefully sculpted line. But with each revision of his answers, I began to worry that the real Dimitrov was fading behind his obsession for self-editing. I began to think that a man who was so concerned with his beautiful image might be afraid of letting the mask slip, might not want to be seen for who he was.

My fears were unfounded. With our last question and answer exchange came the sentence, ‘You do know I have a poem called ‘British Boys’ right?’, with a link to his poem – a miserable paean to Dimitrov’s one summer spent in the UK, pounding the streets of Kings Cross alone whilst a gay night blared out from La Scala’s crumbling whitewashed walls. The poet wanted to be seen, wanted to be touched, but in fact all he did was ‘study his loneliness’. Dimitrov, it would appear, was reaching out to me, finally revealing himself or rather making it clear he had been there all along, waiting to be touched or known. An artist’s life is in their work and this is true of Dimitrov; if you want to truly know the man then just look at his Instagram feed or his Twitter account or Tumblr or Facebook – and then read his extraordinary poetry.

Begging For It is published by Four Way Books