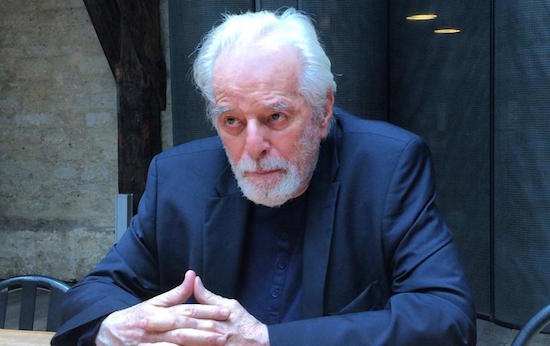

Alejandro Jodorowsky is as close to the archetypal embodiment of genius as you’re likely to find anywhere. The 86 year-old Chilean filmmaker — the man responsible for El Topo, The Dance of Reality and, of course, the near-mythic aborted adaptation of Dune (itself the eponym of Frank Pavich’s 2013 documentary, and the only piece of documentary film released that year which comes close to rivaling Jiro Dreams of Sushi or The Act of Killing) — ticks the boxes of being, both, a creative visionary and an unbridled, Class A Eccentric.

Certainly he’d be hard pressed to argue the latter, hopping as he does in our conversation between complimenting my "beautiful beard", positing on our future gravity-defying civilisation, berating our consumption of fossil fuels and the invention of national borders. (And, of course, there’s that time he recorded an introduction to La Danza de la Realidad in the buff.) The former, though, is called in to contention over the course of our meandering conversation, transpiring that Jodo – avant-garde creative icon — doesn’t actually believe in creativity at all.

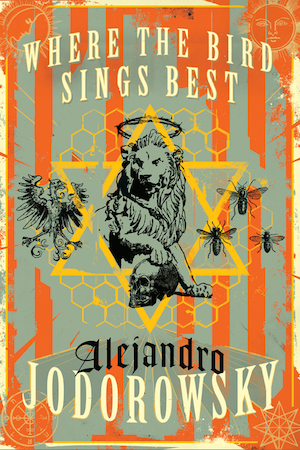

What he does believe in, though, is love and magic: his quasi-autobiographical novel Where The Bird Sings Best is a masterful exploration — comparable to Marquez’s familial saga One Hundred Years of Solitutde and Roberto Benigni’s Life Is Beautiful – of family, mythology and the lengths our minds will go to for self-preservation and a chance to grasp at some semblance of meaning in a world that is so often beyond our comprehension in its beauty and its violence.

Despite having been available in Spanish for some time, and given their due critical praise and place in the literary culture of those countries south of the United States, Jodorowsky’s written works are only now being published (by Restless Books, translated by Alfred MacAdam) in English. The question of ‘Why?’, baffling as it might be, is one for another day. For now, to set the scene: I’m trying, for what I think will be the final time after a half hour of failed calls, to get through to Jodorowsky on Skype; as I imagine it’s getting close to saying ‘call failed’ again he answers, broaches the subject of his English skills (which, once we settle in to a rhythm are fine) and says "Ah, I cannot see you… this will not do."

In context of your work, the book, of your films, and in a wider social sense — how important is myth?

Alejandro Jodorowsky: Any person who has read a little psychoanalysis, Freud, Jung, knows that we have a collective unconscious: the myths, they are necessary for rationalising the contents of the unconscious. In history there were lots of myths. We all have myths — except in America. In America you have superman.

For me the question is… what was the first language of the human beings, what were the first myths? The Epic of Gilgamesh, this is the oldest myth, no? I was searching in the oldest myth, asking "what is the principal search?", and the principal search is always immortality. Gilgamesh, he wants to be immortal – the first purpose of myth is to vanquish death and then to vanquish ignorance. Because we don’t know where we are living; we don’t know the universe; we don’t know what is life, the mystery of life – you cannot create the human being. You can create the physical human being, with the sex – with an animal way – but we cannot create the masterwork, the human being, you cannot create that.

So myth functions to assist us in understanding who and what we are, in the face of actually having no idea at all?

AJ: Yes, yes! I studied the tarot for many years and the tarot is an encyclopedia of myths.

Mythology was a necessary tool in interpreting the landscape – geography, meteorology, astronomy – but how can myth work, continue to fulfill its function, when as a society we know these myths not to be true?

AJ: We need to study myth to be a wise person. A normal person is living just like an animal or a plant and if we want to develop, to grow inside, we need myths – old knowledge, traditional knowledge, these are looking for something that is lost: alchemy was searching for that, magic was searching for that, religion was searching for that. "Where is the centre of the universe?", "How do I find the centre?": some persons, they say the centre is the heart. And the centre of the heart is love. Love is beauty. We cannot know the truth but we can know love and beauty.

So, everything, it all just comes back to love?

AJ: Yes, but not the love to love a person or to love a little animal – no. It is a universal cosmic love. Love is a religion; is a reunion. A reunion with the others – with the other, with the cosmos, a reunion with totality, no? Every part of the totality has a centre and they need to find their own centre. And then I can ask to you, ‘What is your centre?’

Maybe one day I’ll know how to answer that. I’m assuming you do…

AJ: It is in the heart! And in order to come to your heart you need to work inside the words, the language, in the bottom of the language – there is the feeling. Because language is not the feeling, it’s not the truth: it’s only a mask. It’s a useful thing, but it’s not the thing.

Does that work the same way for film?

AJ: Yes! For real film, not for industrial film. Industrial film is like having a relationship with a cigarette, you know? It loves you but kills you! The movie will not kill you but it will not try to save you: you relax yourself, you enjoy the movie, but when it’s finished you didn’t change – you haven’t improved – you are the same. You have escaped from yourself. But the real art is not to escape from yourself, it’s to go inside yourself – to remember yourself. That is the real art.

So that’s what you’re trying to do for other people in your work? In your films, with your books…

AJ: Yes. In my work, in what I do – therapeutic art, I call that. If the art does not heal it is not an art form.

It’s like what Freud says about art, about sublimation, except for the audience rather than the creator.

AJ: Yes. But Freud was not an artist. He was a scientist. Freud only worked with the words, with speaking, speaking cannot heal.

“Industrial film is like having a relationship with a cigarette, you know? It loves you but kills you!”

So, when you’re making a film – or when you’re writing a book – are you doing those things for other people or for yourself?

AJ: First, for me. Second, for the actors. Third, for the public.

You’re still healing yourself then, as much as looking to help anyone else?

AJ: All my life until the end of my life I will try to heal my self. Why? Because if I don’t heal myself then I don’t heal all of humanity and I cannot heal my self if every person isn’t healed also. Excuse me — [Jodorowsky peels away from the camera and, without irony, begins to berate what I presume to be his family for making too much noise. All part of the healing process. He slides back in to shot and asks "What were we saying?". I tell him we were discussing solutions for healing the human race, of course.]

Ah, yes. Humanity – in this world, we are mortal. But humanity we can live till the end of the universe, we can be immortal, we have the opportunity. And as a society we are not alone: as a body we are only one, but in our mind is many, many selves – it is a community.

You’re talking about the Collective Unconscious you mentioned earlier?

AJ: Yes, I believe in it, but not only the unconscious – the conscious. The intellect: the ideas, they are not personal — we receive the ideas, we don’t create them.

So you’re just an antenna, then?

AJ: Yes. The ideas, they come from everybody who lives life every second in the universe, you might call it God — what is God? — it is an energy … it is a mystery. Everything is given to us. Even the love, it’s not us – it’s coming from the universe. We cannot create, we can transform. We are transformers.

So, to your mind, artists aren’t creators at all?

AJ: An artist is searching for what? Searching to transform our life of everyday in to a fantastic life. An artist wants to show to the others what they are — we are not two little idiots speaking about romantic love: we are not that. We are so much more. We are an incredible work of art, every one of us. And art is here to show that.

In a way, then, we’re all our own myths? Our own way of understanding ourselves and one another?

AJ: We have an energy; we have an intellectual energy, we have a sexual creative energy – we need to create something together in order to understand. We have the language of the body and we need to do something together: we need to think together; we need to love together; to create together; to act together. But not making an atomic bomb. If we do that it is destruction. We can do this. We can collaborate; there can be construction. We can go to the paradise. We can.

So, we can’t create but we can destroy? That hardly seems fair…

AJ: We are destroying. We are destroying the planet. We are living in an idiot time. We can be living with another kind of energy — not an energy that is killing the atmosphere. Idiots! We are like fish putting poison in the ocean.

We have a choice.

AJ: We have a choice and we are in danger of destroying ourselves now for the idiocy of industry: making money, thinking they need to grow, destroy the earth searching for petroleum – all this, it is idiocy. They are idiots. The earth has no countries; we invented the countries, but it’s not real.

Alejandro Jodorowsky presenting his film La Danza de la Realidad. Montreal, 2013 from ketty mora on Vimeo.

Given that you say humans aren’t creators do you think we, as a species, have a drive toward destruction because it’s something that we are capable of?

AJ: I think it is the businesses who need the money. God never needs money. God is not the dollar — they think the dollar is sacred but this is a monstrosity: it is not possible. We need another kind of society with another kind of union – the first thing we need to do is to change the money. A few persons have a lot, and a lot of persons have a few – not possible! Idiots! We are heading for destruction…

Taking in to account that it seems clear who’s to blame for our impending doom, it seems a good time to point out that, while your book talks a lot about love, it also talks about forgiveness.

AJ: Yes, of course. The human being, he has not always been himself. We were monkeys and we grow, we grow, we grow and we are not perfect – we are changing. Even our bodies are changing. In 200 more years we will not be white black, yellow, red, person – we will be one kind of person, everyone will be mixed. And then we will have new powers. We will become telepathic; the language will be finished. We will vanquish the gravity; a second, anti-gravity civilisation! We will still have bodies but they will change.

Telepathy, anti-gravity… this leads us nicely on to the kind of classic magical realism in the novel, which seems to me like a natural progression from mythology?

AJ: The secret of mythology is that mythology becomes folklore. And all the magic – the magic of Marquez – is a folkloric degeneration of the myth. My self, I don’t think it is folkloric or magical in that way … I write about real magic not magical realism.

Magic and realism as opposed to Magic(al) Realism, Lo real maravilloso?

AJ: Si. Because, for me, real magic is everywhere but we don’t know how to see that. We need to learn in order to recognise the magic within the world. In every moment something magical happens.

Tradition, folklore and magic are all tied up together, but where does technology — things like Twitter — fit in to that?

AJ: Twitter for me is a very important thing. At first I thought it was an idiot thing where people say what food they have eaten or when they take a shit in the bathroom – communication, but stupid communication. And then I say "No", because it is the art – the literary art – of today. Of our century. And why? Because you are reduced to 140 characters and there you can speak reduced about art, philosophy, science, poetry. Every day I write 15 tweets. Every day at one o’clock in the afternoon I take half an hour to do that … an hour, half an hour. I have a million and seventy-five following [1.09 million at this moment] – a lot of followers – but always speaking about non-personal things, about creating, helping them.

The internet is very important, but it is dangerous if you use it badly. With bad science you make atomic bombs. With the good science you can do miracles. I know a doctor who was in China and operated on the heart of a person who was in Paris. You can do it: you can act at distance now.

That’s pretty amazing.

AJ: Ah! But it is amazing that you are talking with me now! You are there with the beautiful beard and you are with me here! How can it happen? Reality is not what we see: you and me we can speak now – we are in the air! We are communicating with all the humanity in this world.

In terms of communicating, how does writing a book – a novel – compare with making a film?

AJ: It is different, but… in our civilisation it seems we have the ability to be only one thing: you are a writer, or a painter or you are a footballist or you are a solider – but we are a lot of things! Take that [he picks up his phone off the desk] – that is a telephone today but also it is a television, also it is a musical player – it can be a lot of things, not only one thing: it has vibration, I can masturbate my self with the telephone, it can do anything! A human being is like that. You are not only one thing, you are a lot things – when this machine is for listening to music it is one machine, when it makes tweets it is another machine. When I make a picture I am one person; when I write a book I am another person. But anyway, the pressure to create artistically is the same but it’s not the same soul with you – it is another thing.

Making a film is a very big thing; every single image, every thing you can imagine you need to calculate how much money it will cost. All the time it’s money because it is very expensive. To write, no, to go and to write you are alone. Making comics is another thing because you are two: there is me and there is an artist doing the drawing. Every art has another situation. But they are all important.

This is why I still show my films for the first time at the museum, at the MoMA – because it is an art. Making a novel, it is an art, too: this is not Polish history or for the people who like the crime – I wrote this novel to bring you to yourself. To remember yourself. Everyone of us has a complicated family and the most idiot person has a novel.

When you’re working with an artist on the comics, and if we are all receivers, how difficult does collaboration make the process? Or is it a purer form for being closer to the unification you’re looking for?

AJ: Yes, but poetry, you are alone – alone, alone, alone! You make the poetry to discover who I am, no? And then, like a poet, I write a script and I start to make a picture but to make a picture is to work with an army. They are 200, 300, persons – actors, painters, dancers, choreographers, musicians, it’s an enormous collaboration and everyone has an idea. If you are an artist you need to be very strong.

When I tried to make my last picture Dance of Reality, we were in Chile, I said to them, ‘Listen: everyone of you believes that I don’t know what cinema is – because you think you know. Okay! I don’t know what it is, but I know very well what I want.’ And then I will do what I want. Why? Because I want to heal my soul. That’s what I say to them and we do it. But, art is to learn how to be together.

As far as collaboration goes, the Rabbi character in the novel is part collective unconscious archetype, part manifest personality – about as close to total unity as you can get?

AJ: The Rabbi is tradition; he is what you have lost in the history of you, your creation. Every person has a Rabbi – maybe he is not a Rabbi, but an internal guide – and then you need to find what is your internal guide? Is it a kind of craziness? No. Imagination? Who is running the tiller of you? You have a guide. Who is this guide? Your soul. Your really-true self, because we are living in an invention with the ego. The ego what you have now, here, is made by the family, the society and history. It’s difficult.

Then how do we then come to know the real us?

AJ: My self, I came to know that through suffering. Because when you start to lose a lot of things in order to come to yourself you suffer. And life also inflicts this on you; you fail at love, you fail at work, a person you love dies, you have an illness, there is a lot of suffering. Facing the suffering and not being destroyed takes you to your real truth.

Where The Bird Sings Best is out now, published by Restless Books and translated in to English by Alfred MacAdam