The sinews of art and literature, like those of war, are money.”

Samuel Butler

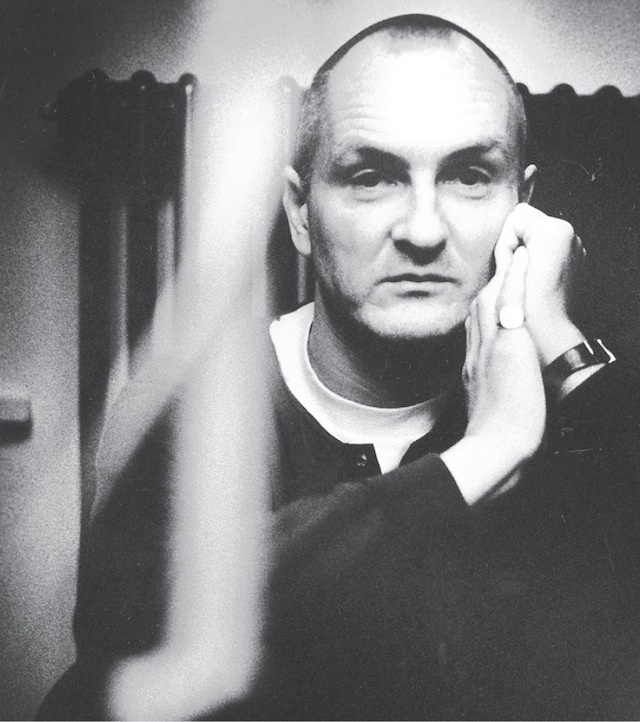

What do we really want from a record label? In the case of Ivo Watts-Russell, it was perhaps rather more than we have any right to expect in the current digital age: an entity that cared about a record as historical document, and one that treated every object upon which its logo appeared as valuable and enduring. It wasn’t a unique idea, and it’s something“ to which a handful of labels still aspire today. But it remains a goal that few – if any – achieve: a company that believed in, as Watts-Russell puts it, “a record for a record’s sake”.

The truth is, only a handful of record companies ever manage to build a reputation even half as formidable as that of 4AD, the label that Watts-Russsell co-founded with Peter Kent while working at a Beggars Banquet record shop in 1980. (Kent left after a year to start Situation 2 Records.) It’s of course even rarer, too, that a label maintains the almost entirely uninterrupted sense of integrity that 4AD could boast up until the mid 1990s (not that it was populated by types given to bragging). But even Watts-Russell was unable to preserve this sense of purity through a decade and a half. The reason he failed? Oh, the usual, familiar, eternal problem, but one rarely so well illustrated: making art usually requires money, and making money usually destroys art.

The story of 4AD is a cautionary tale of how arduous it is to retain one’s principles within the music industry, and it’s one told in great depth by Martin Aston in his new, thrilling, but necessarily sombre history of the label, Facing The Other Way. For Watts-Russell, it’s a tough read: the former boss is clearly a little uncomfortable that he’s become the focus of a book about a label that prided itself on its ‘artists over execs’ approach. He was, after all, never a larger-than life figure like his contemporaries Tony Wilson or Alan McGee, and instead an enigmatic individual who tried to allow his releases to speak for themselves.

“I did say to Martin quite early on,” he admits, when asked how it feels to find himself the book’s star, “‘Could you please stop using my name so much? Can’t you just say ‘the company’, or ‘4AD’, as opposed to ‘Ivo, Ivo, Ivo’, because in many ways it feels so personal?’” But there’s no way around it: the story of 4AD’s first two decades is, in many respects, the story of its founder. Elusive though he may have been, it was his aesthetic instincts that underpinned its creative direction, at least until he moved to Los Angeles in 1994. The pattern of his career, furthermore, reflects that of 4AD itself, and is simultaneously an illustration of how destructive the business can be, and how passion alone cannot always surmount personal problems.

Ivo Watts Russell

Back when Watts-Russell first set up 4AD, it had arguably never been easier to create a label. Punk had helped expand the avenues of distribution, and technology was making it possible for individual musicians – albeit expensively – to make music in a wholly new way. These days setting up a label is even easier: one only has to look at the sheer volume of records released every week, and the number of labels in brackets after artists’ names, to see that it doesn’t take a genius to start one. But few post-punk labels survived, equally few of those set up this year will make it beyond a handful of releases, and less still will make a lasting impression. After all, most labels are set up on a whim, a wing and a prayer, with no long-term vision and only a desire, at its most articulate, to release music that the founders like “and if anyone else likes it that’s a bonus”.

Initially, Watts-Russell was little different. “When I started 4AD,” he says down the line from his remote home outside Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he now lives, alone apart from his dogs, “I had no expectation of anything other than selling out our first pressing of things. I used to think that if something moved me sufficiently then there would be enough people out there who would also be moved in a similar way to make it worthwhile to get involved.”

Like many introverts, Watts-Russell – the product of an upper-middle class family who grew up on a farm near Oundle, in Northamptonshire – had developed his love for music while young. He still talks with passion of how music helped articulate his emotions as a youngster, of the romance of record sleeves, and of the joy of familiarising himself with their contents. Slowly, throughout the 1970s, he gravitated towards the industry, his devotion fuelled by the punk years. He travelled a little, but mainly worked in record stores, finally ending up at the Beggars Banquet shop. There, impressed by Watts-Russell’s engagement with the emerging independent, post-punk counter-culture, his boss, Martin Mills, bankrolled 4AD’s inception as a hothouse for the burgeoning label he was now also running.

“I stand by a statement I’ve made on many, many occasions,” Watts-Russell emphasises, “that working, or being based in, a record shop, anything that came in on an independent label – especially off the Rough Trade van – was worth listening to.”

But, before the label had even been founded, Watts-Russell was starting to experience the fatigue that most people who work in the business go through sooner or later: the longer he went on, the harder it became to maintain his enthusiasm.

“I can remember the feeling after one of the import vans had just visited,” he recalls from the silent terrace of his desert house, as ice cubes rattle in his glass. “I’d gone through whatever new releases they had, and there’d be a pile on the floor of 25 albums that I just couldn’t wait to hear. But it was a question of doing that: of hearing them as opposed to really listening to them. In other words: to be able to form an opinion about them really quickly. The record industry to this day – actually, more so than ever, because they’re getting hit from every fucking angle – still revolves around people making up their mind about something very, very quickly, and quite frankly probably never ever changing their mind about it. People who work in the industry are very, very busy. They have to make a decision, and once their decision is made it’s unhealthy for them to change their mind about it.”

Such stubbornness, often interpreted as determination, can sometimes help define a label. 4AD clearly benefited from its co-founder’s unquestionably idiosyncratic tastes, and though these were initially far from the mainstream, after a while the mainstream started drifting in the label’s direction. Right from the start, Watts-Russell had displayed an impressive ear for discovering unusual talent by signing Nick Cave’s Birthday Party, and he’d also made commercial waves in the label’s first twelve months, scoring a Top 75 album with Bauhaus’ debut. (This translated into a number one in the Independent Charts, established earlier that same year.) As the 1980s edged forward, the label slowly became known for a ‘4AD sound’, a largely indefinable tag – given the presence on the roster of curveball acts like The Wolfgang Press – but one inspired by the ‘ethereal’ musical nature of Cocteau Twins, Dead Can Dance and Watts-Russell’s own project, This Mortal Coil. Even 4AD’s low profile acts were interesting: amongst them were Matt Johnson, who would later go on to enjoy success as The The (and whose album Watts-Russell only reluctantly reissued under Johnson’s better known, adopted name when Johnson later insisted he do so); Modern English, who would enjoy American success after being licensed by Sire Records in 1982; and Colourbox, who were one of the first acts to employ sampling outside of hip-hop culture.

Of course, while obstinacy can, in the right circumstances, be a virtue, it’s sometimes adopted as a survival strategy. Watts-Russell chuckles knowingly when it’s suggested that the industry is full of people who mistake their opinions for truth, and sighs sadly when reminded how some individuals regularly insist that a person’s tastes are ‘wrong’.

“One does get jaded by things,” he admits, “and I’m sure that I learned to create a buffer so that within a number of years maybe I came across as an untouchable record company person. I certainly hope not, though.”

Still, this mind-set helps one endure the industry: there simply isn’t enough time to reassess one’s judgements on a regular basis. There’s too much music to hear, and too little time to listen to it.

“I’ve always, always really disliked Pulp,” he laughs, “but I’m not sure if I’ve ever really heard them! So I’m absolutely guilty of having made up my mind based on probably something twattish that Jarvis Cocker said, who I’ve later learned is a very smart man and very humorous. But at the time it was not something for me. Maybe it’s time! What do you reckon? Should I be going out buying Pulp records?”

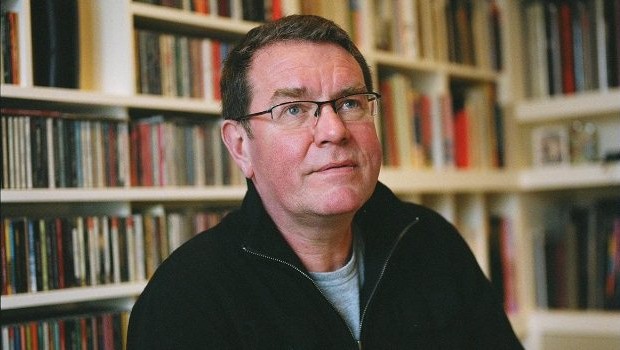

If Watts-Russell’s singular vision was one of the elements that soon set 4AD apart from other labels started by enthusiastic music fans, the other was the work of Vaughan Oliver, a designer whom Watts-Russell hired full time in 1983 after he’d previously worked freelance for the label. His contributions – first with Nigel Grierson as 23 Envelope; then with a variety of collaborators, including Chris Biggs, as v23 – were immediately recognisable, and helped make the label’s releases instantly identifiable. Each act was lent a peculiar style of its own, the images often unexpected – he posed naked with a belt of dead eels for the cover of The Breeders’ Pod, Aston reveals – and yet oddly intuitive. Indeed, Oliver took an almost fetishist approach to his work – one that recalled, for instance, the work of Meret Oppenheimer, though Oliver denies she was an influence – and chose to use his art to communicate the music’s contents almost subliminally, dispensing with artist photographs on sleeves altogether. His obsessive nature reflected Watts-Russell’s fanatical fascination for the music perfectly, and buying a 4AD record became about more than simply wanting to hear the music: it was about wanting to enter the universe that Oliver, Watts-Russell and, most importantly, the artist had created.

Vaughan Oliver

“I like the idea of the sleeve seducing you into its world,” Oliver explains, and he and his colleagues did exactly that, reinventing the concept of what an act’s image actually is. As the label progressed, however, and its reputation grew, inevitably there were those who felt threatened by its working methods. Watts-Russell’s vision of a label in which the music, and the record, were the only things that mattered, began to get besieged from the inside. For every act that recognised the benefits of being part of such a distinctive set-up, there were others who believed increasingly that they were becoming secondary to the very entity whose success they were helping to build.

In Aston’s book, Cocteau Twin Robin Guthrie comes across as especially bitter. When asked how he feels about this, Watt-Russell tries not to get drawn into a slanging match, offering little more than, “I’m not going to get into an analysis of Robin Guthrie. What I would say in response is, even with all of the cruelty that Robin was capable of, I still believe that there was genuine respect and love for each other.”

Though one might sympathise at times with Guthrie’s prickly resentments – “They created a look for the label – they wanted the same celebrity as the bands,” is just one of the accusations Aston recounts from his conversations with Cocteau Twins’ co-founder – one suspects that they have more to do with the shifting of Guthrie’s own expectations as the band’s career took off. It’s something that Watts-Russell unintentionally hints at when asked whether, once one has learned certain rules, one can ‘unlearn’ them.

“When it started, or a few years into it, meeting people from Grangemouth in Scotland,” he recalls ruefully of the label’s early days and his decision to sign Guthrie’s band, “they were full of post-punk attitude – actually, punk attitude – of not even wanting to have their photograph taken or whatever. But behind all of that, one learned that there was this expectation that, regardless, they were going to get on the cover of a magazine, not just in a magazine. The idea that they were entitled to that developed quite quickly.”

Watts-Russell nonetheless claims this was never something he resented. “If you were to take on representation of an artist,” he explains, “and contractually have them committed to you, and you to them through advances et cetera, it was kind of an obligation to at least attempt to do what by then everybody else was attempting to do, which was expand their visibility and therefore their profitability and popularity.”

But this too represented another destructive component within 4AD’s evolution: when the need to satisfy the media – and, of course, to sell records – entered the equation, it became harder to respond to music on a purely aesthetic level. Each new musical note began to represent a potential bank note, and every album tracklisting morphed into a spreadsheet budget. Within every label, the failure of a release – whatever the reason, whether it be the release date, the artwork, the band’s live presence – leads those involved to question their instincts, but once those questions have been explored, formulas evolve, and there’s no turning back from that point on.

Similarly, success, too, can have a detrimental effect. When Colourbox – by whom Watts-Russell had stood loyally for a number of years, despite their painfully slow production rate – teamed up with A.R. Kane to form M|A|R|R|S, their subsequent 1987 number one hit should have been cause to rejoice. Instead it brought with it discord – the musicians fell out in an especially ugly fashion, never to work with one another again – as well as lawsuits threatened by pop producers Stock, Aitken and Waterman, who claimed that, amongst its many samples, ‘Pump Up The Volume’ benefited from the illegal use of an excerpt of their recent hit ‘Roadblock’. Though the case never came to court, it soured the victory that the label should have enjoyed for scoring Rough Trade Distribution’s first ever number one.

“It actually shut that door of opportunity,” Oliver remembers, “because it was surrounded by so much ill feeling and money, and the Stock, Aitken and Waterman thing, and what it did to people. Ivo hated it. Ivo wouldn’t go to the pub to celebrate it. It was something that he almost rather wished hadn’t happened.”

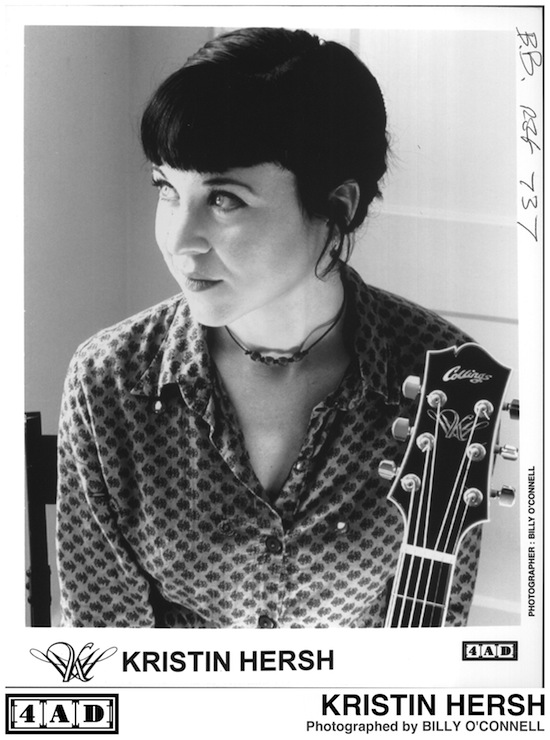

In conversation, Watts-Russell refers to that time, and the efforts that had gone into achieving that success, as perhaps being “the first step on the rung of the ladder that I ended up falling off.” Certainly, combined with the next wave of accomplishment that the label enjoyed soon afterwards with the Pixies and Throwing Muses, it helped change the culture of the company, and not necessarily for the better.

“That was probably the most exciting time at 4AD for everybody,” he tells me, “because it was on the back of a proper chart hit single, and with two independent American bands, people just gobbling it up. But I did notice something that was never important to me before, maybe [because of] the privilege of being at the top of the label: the pride everybody who was working at the office felt at having a visible commercial success. That was tangible, that their parents or their friends could recognise a number one hit single and then top ten albums and things. I noticed that [this] seemed to be important. I can’t blame them for directing me into the way that the label started to behave, but I did take note of that. And I guess, yes, absolutely, when you’ve had Throwing Muses and the Pixies having hit albums, everybody who releases an album now thinks that this is a possibility for them.”

Indeed, as 4AD had grown, hiring more staff and opening a US office, the pressure to maintain success had also increased, and each release took on greater significance for both financial and artistic reasons: without income the label couldn’t pay its bills, and without further success not only would its acts become disgruntled, but the label’s image would suffer. Where once they’d existed on a hand-to-mouth financial basis, growing at an organic pace, 4AD now started to play the same games as other labels, and, in so doing, began to compromise its identity.

“Maybe Ivo thought there was another level,” Oliver concedes generously of the change in the label’s approach. “Maybe he’d been treading water. Maybe he thought things had plateaued out a little and he was wondering where to take it next. I don’t know. I’m kind of recalling now that I was very curious about his insistence that Lush had a big hit in them. I didn’t think that he would ever think like that, especially with a bloody band like Lush. I didn’t get it.”

Oliver, however, sympathises with the battles his colleague faced trying to preserve the very thing that had made 4AD special: his love for music. “I think the first thing Ivo said on day one,” he remembers, “was that once you’re in the music business, it might kill your appetite or hunger on that side of it. Maybe you can’t be touched in the same place. I was able to immerse myself in the world of that music without it being clouded or coloured.”

For Watts-Russell, the overwhelming need to maintain the label’s fortunes slowly became a crushing weight, and it added to another that he already carried with him on a daily basis, albeit one which no one else really knew about: his depression.

“He was dark,” Oliver confirms. “He carried his black dog all day long, every day. But somehow he managed to function.”

Slowly, Watts-Russell’s interest in the label he’d curated with such love and attention began to decline in the face of factors that most likely he’d never imagined in 1980. Quite simply, his instincts had been polluted by the business: he could no longer hear music with pure ears. Every record he confronted was no longer a document: it was a product. Seeking a new start, he moved to LA in 1993, and began handing over A&R duties to associates. If the label had already lost its soul, now it lost its direction entirely. Acts like GusGus and Scheer might have had their merits, but they had no place on his vision of the label, and, in 1999, he sold his half of the company to its original bankroller, Beggars Banquet’s Martin Mills.

33 years after it was founded, 4AD is still with us. In fact, it enjoys as much – probably even more – commercial success than it ever did during what was once known as its heyday, the mid 1980s to the mid 1990s. This year alone, its signings The National peaked at number three in the UK album charts, while Stornoway went to number four. It even boasts a "national treasure", Scott Walker, whose most recent collection, Bish Bosch, confirms the company’s ongoing creative ambitions.

No doubt those who work for the label would contend that its core values remain the same as ever, and certainly many of their releases can make a significant claim to being of genuine artistic value, whether it be the sleek and shiny electronica of Grimes, the art-pop of St Vincent, or Bon Iver’s initially intimate, now grandiose, songwriting. But, though it remains one of the great British record labels, 4AD is not the same as it was. The sense of the unforeseen that surrounded so many of its releases is often missing, and its catalogue now contains large amounts of artists signed to former imprints since folded into the Beggars Banquet empire, including the parent label itself. It’s as though owner Martin Mills recognised that the 4AD brand was his company’s most valuable, but the reasons why were forgotten.

Even 4AD’s artwork has been compromised. That the once timeless documents that he and Oliver laboured over are being released in a flawed condition is clearly something that bothers Watts-Russell. “I just don’t understand why people there don’t recognise the value of what a certain combination of people created. The first Ultra Vivid Scene album, with the embossed gaffa tape floating over the edges of the sleeve, is one of the most amazing sleeve designs of all time. And I get angry when these things are in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, because there are people there who recognise it, and the label itself just does not.”

The fact that 4AD’s once beloved, adventurous packaging has been – at least partially – sacrificed to commercial needs is, in Watts-Russell’s opinion, only part of a wider unalluring picture. That labels can’t imagine that the general public is interested in elegant, lovingly prepared releases remains mysterious to him.

“Even if you’re spending thirty dollars, I don’t think it’s much to spend on something that’s a nice object that gives you pleasure from looking at it and wants you to be delicate and tender with it, but actually inside contains this incredible musical work. It’s mind-blowing to me that people would think that that is expensive, or that people wouldn’t want it. So instead what they do is they come up with… It’s not as bad as the crazy days of plectrum shaped vinyl, but they’re constantly coming up with these deluxe versions of things that are just… they rattle! I hate it when I get something and you just shake it and it rattles because it hasn’t got an inner sleeve, or they haven’t done the packaging properly, and the shrink-wrapping is so fucking tight on it that it’s bent the corners before you’ve even got it out of the packet!”

Fortunately, Watts-Russell is aware that there are others who, like him, continue to consider music a serious concern, worthy of respect. Occasionally he even allows himself to be flattered that some of them were inspired by his work, though it’s something in which he takes an embarrassed comfort.

“In the late 90s,” he recalls fondly, “I suddenly realised that a bunch of music I was listening to – Labradford, Stars Of The Lid, Wendy and Carl, Pan American – they were all on this Chicago label, Kranky. At that time they had no barcodes on their CDs and things. I thought it was brilliant. They were just saying, ‘This is what we do. A barcode’s not going to make any fucking difference. Stick one on yourself if you want to stock it at Tower Records or whatever.’ So I called up Joel [Leoschke, founder] just to say, ‘Well done!’ Joel said something kind, about being in part inspired by 4AD when he was younger.”

Other labels, too, pop up from time to time, their aesthetic comparable, their attention to detail analogous: Light In The Attic’s reissue programme, for instance, or Erased Tapes’ sense of a community shared by its musicians’ common values as much as common musical interests. The chances of another label as carefully considered as 4AD emerging, however – as it existed for those first dozen years or so – remain small. The digital age has all but annihilated the concept of extravagant packaging for anything outside of a niche market, and reduced turnovers for record labels insist they play safer and safer. There’s little room for genuine mavericks in the music business these days.

“I think the world would be a better place,” Oliver concludes, “if Ivo had set up another label and started from scratch again, doing it because he loved it, and not because he wanted to sell records.”

But that doesn’t seem likely. Asked how he keeps busy, Watts-Russell laughs.

“I try not to! I gobble up music still – not necessarily contemporary – and I read. And films: I always loved films. I love the fact that getting out of the business of music, I am really willing to change my mind about something – music and films or whatever – and to spend more time with it. I don’t think I felt that I belonged in the music industry…”

Facing The Other Way: The Story of 4AD by Martin Aston is out now, published by The Friday Project