Zheng Bo, Pteridophilia 1 (2016) Video (4k, Colour, sound), 17 min

Ferns do not reproduce in the same manner as most other plants. They have neither seeds nor flowers; they are asexual. Their reproduction relies on spores, a single cell organism that gets dispersed by the movement of the wind. The fern symbolises the wholeness of the tao. It multiplies alone, its place in nature established existing within and without itself.

Zheng Bo’s videos are at a first glance puzzling. In the film series Pteridophilia (pterid- from the Greek for ‘fern’), we see young men performing sexual acts with ferns: licking them, caressing them, giving them oral, fucking them, using them for BDSM play, urinating on them, pricking their penises with them, making masks with them, etc. All these acts are manifestations of human sexuality, even if we might think of some of them as taboo, and so it is not unsurprising that they should find a place in this newfound intimacy with nature.

These are not exoticised bodies or desexualised bodies, as tend to be depictions of Asian men. Their sexual qualities are visible, overt, and woven into the landscape. As the performers’ bodies move through the landscape, their sinuous shapes become more and more like the plants themselves. Though they establish relations with each other and there is a clear underlying homoeroticism in their gazes and that of the camera, there seems to be a greater emphasis on the vicarious character of the body. They become extensions of the landscape, ferns themselves, autonomous of each other and able to be realised solely in this union.

Sexuality has long been a source of fascination for psychologists, artists, writers, thinkers, and for most humans who have drawn breath. This has been evident in the last century, as discourse surrounding the sexual nature and behavior of humans has risen, creating such specialties as sexology, sexual therapy, and couples therapy. In the arts, portrayals of sexuality date as far back as the Stone Age (cave drawings of vulvas have been found in Moravia and the south of France). This interest is unsurprising as the biological force to procreate has carried our civilizations forth. But sex is not just a form of reproduction but also an expression of pleasure.

Depictions of sexual abandon were not unusual in the chambers of ancient Rome, as is clear from some of the murals that survive in Pompeii. In Medieval Europe, though less ubiquitous, there were still sexual depictions – mostly connecting it to the shame of the Catholic faith. Representations surged throughout the Renaissance, in the art of mannerism and the baroque, often appearing in connection to illustrations from classic antiquity, especially Ovid’s Metamorphosis. All artistic forms thereafter have been accompanied by artworks depicting so-called “lascivious” acts. But in perhaps no age has this been more apparent than in modern and contemporary art, from Mapplethorpe to Koons, Emin, Ruscha, and so on. It is rare to find an artist whose work doesn’t at some stage relate to the sexual impulse.

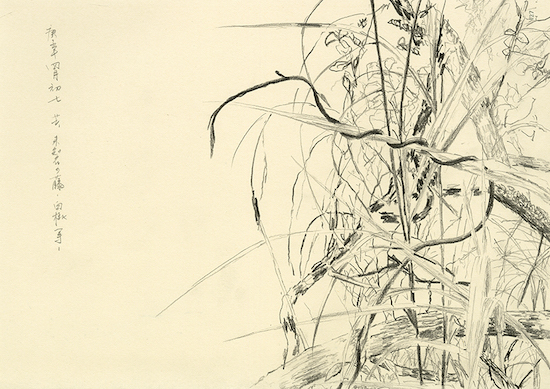

Zheng Bo, The Soft and Weak Are Companions of Life 柔弱者生之徒, Installation view with Drawing Life (2020–ongoing). Pencil on paper. Photo: Bruno Lopes

In Asia, portrayals and studies of sexuality have been just as prevalent, though often not studied in our Western-centric conception of culture. There is the Kama Sutra, not just a manual for sexual positions, as we tend to think of it in the west, but a guide for spiritual living that includes sex and love. In China, depictions of sex in art were rife until the end of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). The Cultural Revolution came to institute new taboos and a new bio-political control of reproduction. Since then, sex has become further “normalised” in the People’s Republic, nevertheless this applies merely to heterosexuality.

Zheng Bo’s Pteridophilia 1-4 (2016-ongoing), currently on view at Kunsthalle Lisbon, appears in this context but here the focus is on sexuality’s relation to nature. Zheng’s approach reaches beyond ecosexuality or sexecology. The work proposes an understanding of spirituality as connected to intimacy and sensuality. And, although there is a transmutation between humans and nature, we find none of the vindictive character of Ovid’s Metamorphoses is present.

Zheg Bo, Drawing Life (2020–ongoing). Pencil on paper, each page 21cm x 29.7cm

The title of the exhibition “The Soft and Weak Are Companions of Life 柔弱者生之徒” comes from a sixth-century Taoist text, the Tao Te Ching. Taoism focuses on the individual’s relation to nature and to its natural course or way, the tao. In Pteridophilia, sexuality surfaces in the natural world under various guises, yet parallel throughout, is the idea that sexual pleasure and intimacy can be obtained through nature. Zheng’s work presents this communion with nature as a pursuit for spiritual fulfillment and a way of life that is plenary.

The exhibition at the Kunsthalle Lisbon also includes drawings made by Zheng this year, which seem to complete this cycle of a connection with nature. Drawing Life (2020-ongoing) is a series of drawings of plants that almost look like pages of a scientific-journal or a herbarium. The artist made them in Lantau Island, Hong Kong, where he is based, since the start of spring. Zheng captions each with the plant’s name. In a way this identification process emerges as an impetus to find simplicity. The philosophy of the tao is more significant in the jumble that is the Covid-19 crisis.

Zheng Bo, The Soft and Weak Are Companions of Life 柔弱者生之徒, Installation view with Pteridophilia 4 (2019) Video. Photo: Bruno Lopes

This had not been the first time I came across Pteridophilia, which was on the 2019 exhibition “the Garden of Earthly Delights” at the Gropius Bau in Berlin (where Bo is artist-in-residence), but the sense of intimacy at Lisbon’s Kunsthalle changed my ability to be taken into the language of the films. At Gropius Bau, the work had been installed among potted ferns and it appeared in the wider context of the show. Though the effect and concept of the work were not lost (nor its beauty); in Lisbon, there is the possibility to experience all the films in a continuous timeline as a stand-alone experience. The drawings offer an introduction which signals the importance of nature. Even descending the stairs of the Kunsthalle building mirrors the experience of sinking into the subconscious, a domain of desire and the invisible.

Zheng’s work is singular in the way it deals with sexuality, a saturated theme so difficult to innovate upon, as is his interest in nature. Currently he is developing a project at the Gropius Bau to find out how plants practice politics. Pteridophilia challenges our often strict perceptions of sexuality and spirituality. The two do not have to be separated. Though, perhaps, this realisation is only a reflection of how taboos and preconceptions have permeated something as wholesome as sex in our societies.

Zheng Bo, The Soft and Weak Are Companions of Life 柔弱者生之徒, is at Kunsthall Lissabon until 29 August 2020