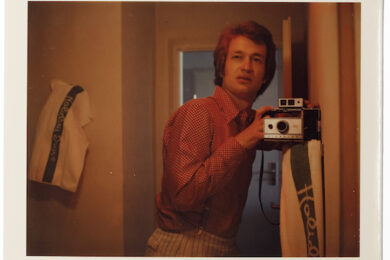

Wim Wenders, Self-portrait, 1975 © Wim Wenders, Courtesy Wim Wenders Foundation

"That’s a lovely picture," says Alice. "It’s so empty."

The picture is a Polaroid photograph taken from an airplane window of one of the wings in the sky. Alice isn’t real but actually a character played by Yella Rottländer in Wim Wenders’ 1974 film, Alice In The Cities. The film follows the extenuated journey of Alice after her mother, Lisa (Lisa Kruezer), agrees to let a fellow German, Philip (Rüdiger Vogler), take her back to Germany from America several days ahead. The problem being that Lisa doesn’t show up at the arranged time, with Phil then left to find where Alice lives. The endless journeying around the country, through industrial towns, empty motorways and edgelands, is Wenders’ filmmaking typified in this period. Essentially, however, Phil documents much of the journey with his Polaroid camera; a journalist, now lost for words, resorting to the newly instantaneous analogue in order to try and capture what he experiences.

There’s something autobiographical about this in that Wenders himself was obsessively taking Polaroid photos in the same way as his character, documented and collected together in the current exhibition at The Photographers Gallery, Instant Stories. The line is blurred between fact and fiction in the exhibition’s array of interesting travels, landscapes, people, and everything else usually associated with Wenders’ cinema. He seems to have lived his films as much as his contemporary of New German Cinema, Werner Herzog.

Where Wenders differs is in his interest in Americana – or at least its sense of the road journey, finding a European flavour of despair and quietude in the vast highways of the US and in Europe itself, more typically favoured as symbols of freedom and exploration.

The exhibition could be split into three intriguing perspectives though it’s heavily segmented into detailed themes. Trips to Japan and to Yasujirō Ozu’s grave sit alongside trips to cafes in Paris, bars in New York, and shoots in the middle of nowhere. But it’s Wenders’ perspective and how it lapses between realities that is the real interest as it provides a glimpse into how the man worked in his most effective and prolific period.

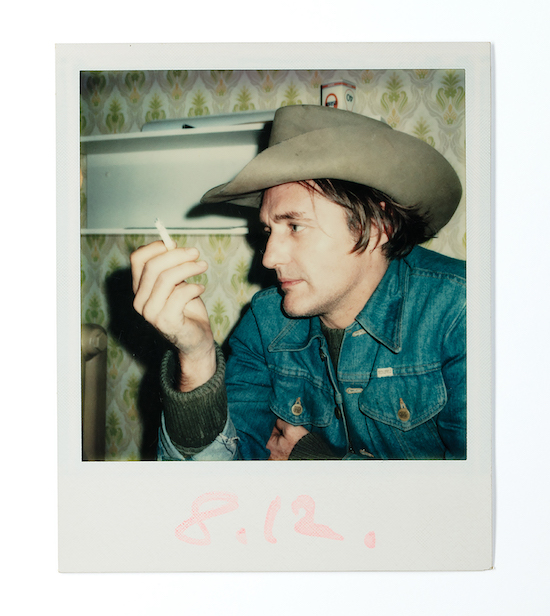

The first perspective is from within the fictional realm of his films: Polaroids taken by fictional characters within his narratives. This hasn’t happened too often but is a marked presence in both a huge blow-up of Phil from Alice on the wall and the clips installed on a loop, including the famous sequence of Dennis Hopper repeatedly trying to take what could be described as a profile "selfie" with a Polaroid camera in the 1977 film, The American Friend. The sound of this repeated sequence echoes through the whole of the exhibition’s second floor and is strangely pleasant. But, alongside the video are some of the actual Polaroids that were created from this sequence; showing the intriguing disjoint between the harsh flash of the camera and the precise lighting within the film.

WimWenders, Dennis Hopper, 1976 © Wim Wenders, Courtesy Deutsches FilminstitutFrankfurta.M.

Related to this is the second perspective which showcases many behind-the-scenes shots of actually making the films. Fictional shots of Hopper sit alongside real photos of the actor. The likeness between these and the atmosphere of the finished films again shows how permeable Wenders’ worlds were in this period.

He suggests in an accompanying video for the exhibition that it was the momentary nature and immediacy that drew him to the Polaroid camera, calling it "the last outburst of a time when we had certainty, not only in images." The confidence to play around with this form is most present in these behind-the-scenes shots, pre-empting the future interest in what must have seemed relatively normal processes in making films.

The best example of this comes in a pair of photos related to Alice. The first is a picture of Wenders himself taken by Rottländer, a portrait looking up from a low angle produced through the height of the photographer. The second shows a portrait of Rottländer, looking down on her whilst she holds the first portrait of Wenders in her hand. The immediacy is clear in this image but there is nothing overly ponderous about it. Like most of the photos, there is at the least a sense of fun and experimentation, at most a certain curiosity.

Wim Wenders, Sydney © Wim Wenders, Courtesy Wim Wenders Foundation

The final perspective is purely of Wenders himself and his journeys around the world; the overriding image of the exhibition being a city-scape seen through his famously rounded spectacles. These begin with documentation in hotel room mirrors before getting down into the streets to wander. His pictures of New York especially capture a moment in the city before the process of social sanitisation had begun. If not for the recognition of the Polaroid aesthetic, it wouldn’t be too difficult to believe New York to actually have possessed that Polaroid look; the whiteness of the flash leaving everything with a gleaming shine in a blue-green haze. Images of shelves of Campbell’s Soup are the perfect example of this, toying with that Warhol Chelsea Hotel world, an eye that found merit in the orderliness of advertising designs and imagery. Alongside this detail, however, are a huge variety of cityscapes, the best often being either taken at night or in black & white; that sense of the city seen as a blur of lights through a rain-spattered taxi window.

With this sense of celebration – of Wenders and his films, of the cities he visited, and even of the form itself – there is a surprising feeling of sadness in the exhibition. The director has already suggested the difference in Polaroid between then and now; the casualness lost and turned more into a process, another aesthetic to be brought out for the latest branded photographs whenever needed. Wenders’ films from this period rarely presented any definite conclusion, their wandering or driving seems endless as if something was lost and impossible to ultimately find. I was reminded of Don DeLillo’s novel, Americana (1971), a similar story of a filmmaking wanderer whose impetus to step-out into the world is all but swallowed up by the momentum of the constant journey. But Instant Stories shows that the Polaroid wasn’t simply immediate in the technological sense but in terms of the eye of the photographer, wandering and casual.

Polaroids are a mindset as much as an aesthetic, one that, even with the instantaneous character similarly found in the cameras made today, is not so easily replicated when wielded with the cold precision of the digital mindset.

Wim Wenders: Instant Stories runs until 11 February 2018 at The Photographers’ Gallery in collaboration with Wim Wenders Foundation and C|O Berlin Foundation